To mark six months since a pandemic was officially declared, BuzzFeed News is publishing The Lost Year series: six stories of six people from six different age groups across the US. Each day this week, we are profiling a new person to see what toll the coronavirus has taken on their lives. In this final installment, we meet a woman in her eighties in Southern California.

My grandma’s pandemic began with a decision.

At the beginning of March, her husband — whom we called “Ông,” the Vietnamese word for grandfather — lay in a hospital bed in Southern California breathing shallowly. The room was like the dozen or so others he had been in and out of over the past six years: sterile and stark with the same turkey meatloaf, apple juice, and guest chairs worn in by waiting bodies.

My grandma — or Bà, as we call her — had seen the television and read enough in her Vietnamese newspapers to know about a fast-moving virus that ravaged an elderly nursing home near Seattle in the weeks before. Now here she was, assessing her choices as another nurse — this one at a 6-foot distance and through a mask — explained to her the different options she could take with her 89-year-old life partner.

He could be released and come back to the hospital every time he couldn’t breathe or passed out, while also continuing his life-extending dialysis at a nearby center three times a week, the nurse explained. But that came with unknowable risks. With uncertainties looming over the transmission of the coronavirus and the policies around patient visits, there was the possibility, my grandma thought, that she may not see Ông again the next time he passed through the doors of some emergency room.

The alternative was for him to return home and live out his last days in palliative care, where he’d at least be surrounded by family.

She made her decision, but in some ways the virus chose for her. Ông died on April 4.

Unlike more than 190,000 other Americans, Ông did not have his life cut short by the coronavirus. It did not speed up a decline set in motion years ago by diabetes, broken kidneys, and a failing heart. But even though Ông didn’t die because of the pandemic, he did die during it, forcing my grandma toward impossible decisions and eventually leaving her alone for the first time ever in a country she adopted 45 years ago.

The disarray and social upheaval caused by the virus took a life event that’s already fraught for most — the final days of a spouse — and made it unbearable for my Bà, an 82-year-old woman whom I had never seen cry until the 30-minute closed casket “viewing” of her husband’s body.

“I can’t even imagine what she’s doing now with the pandemic. As a person in that generation, it’s so hard to adapt.”

She is still grieving. Even though Bà has moved in with my parents, trading in the familiar hub of Little Saigon in Westminster for a whiter, more affluent Orange County suburb, she at times seems lost. On a visit home last month, I sometimes found her sitting in the garage by herself for extended periods of time, or praying in her bedroom. Without Ông, whom she had spent the last six years caring for around the clock, she seems to lack a sense of purpose.

“A core part of her identity was taking care of him,” my 24-year-old cousin Sarah Nguyentran, and their eldest granddaughter, told me. “Most of her life gravitated around him and going to temple.”

“I can’t even imagine what she’s doing now with the pandemic. As a person in that generation, it’s so hard to adapt,” she added.

As my grandmother and I sat outside a Vietnamese dessert shop in Westminster, I could still sense how raw it was. “It was five months ago,” she said, searching for the English words to describe her pain. She ended up settling on the simplest explanation: “It’s just so, so sad.”

For older people like my grandma, the pandemic has made a lonely time even lonelier. Because of their susceptibility to the virus and COVID-19’s compounding effects on those with preexisting conditions, many older citizens have been forced into isolation, preventing them from leaving their homes or visitors from entering. Underscoring that necessity: Some 40% of deaths in the US have come from patients and staff at nursing homes and long-term care facilities.

In one study from the University of California, San Francisco, that’s been ongoing since April and is yet to be formally published, preliminary results showed that 41% of older adults living in San Francisco experienced worsening loneliness because of COVID-19.

Bà is perhaps fortunate that she’s not in a nursing home and has the ability to live with her oldest daughter, but that doesn’t mean she’s without issues. She has diabetes, which has largely prevented her from leaving the house besides her morning walks with my mom around the neighborhood. She’s also lost the support systems she relied on while Ông was sick — her younger sisters and neighbors who she used to see in Little Saigon and her Buddhist temple, which she visited every weekend. In the last months of Ông’s life and in those after he passed, she sometimes stopped eating.

“Seemingly overnight, we saw our social structures dissolve as we were all forced to socially distance ourselves,” Carla Perissinotto, one of the UCSF professors leading that study, told a Senate special committee on aging in June. “We do not know how long we have to be lonely or isolated, or how severe this must be for us to have lasting negative consequences.”

It’s hard to tell how Bà is handling it all. She’s small and fair, and looks healthy for her age. She comes to life when she chases the family dog around the house, or when she asks me, as she always does when I’m home, if I’ve lost weight — her way of saying I’d be eating better if she were cooking.

“And when death is calling you, you should nod and be willing to go.”

But it’s clear the thought of spending her last days riding out a pandemic is weighing on her. During our short time together last month, I asked her if she feels the coronavirus has cost her anything. Does she wish she had more time with Ông? Does she wish she could see her family? Does she wish she could see me more?

“In Buddhism, anything can happen. Tragedy can hit,” she said stoically in Vietnamese. “And when death is calling you, you should nod and be willing to go.”

She’s lived a full life, she later added, noting that she’s ready to accept whatever comes next during or after the pandemic. I’m not sure I believe her.

“With or without coronavirus,” she said, staring down at her hands, “I just don’t want to be a burden.”

Both sides of my family have never been good about sharing their emotions. On my dad’s side, which is made up of Vietnamese immigrants of Chinese descent who settled in Germany after the war, there was the sheer physical distance and language. On my mom’s side — her parents, two brothers, and a sister, all of whom ended up in Southern California — there was just a tacit understanding that we didn’t talk about how we felt. There was other stuff to catch up on: grades, sports, work. Why waste it talking about something so intangible?

The shortcomings of that approach were apparent in April when, robbed of my ability to show physical affection, I had no way of comforting Bà as I arrived at her home hours after Ông had taken his last breath. I’d been staying with my brother an hour from my parents’ home, worried that I could unwittingly transfer the virus if I stayed with them. He and I made the trek up as soon my mom called that morning crying.

People have written about the pain of watching a loved one wither away over video chat after COVID-19 froze travel, forcing them to settle for a pixelated rectangle on an electronic device. I’ve reported on families who were unable to be with their mothers and sisters as they lay dying in the intensive care unit, overcome by a coronavirus they’d contracted at their places of work. They’ve confided in me and shared their pain.

But nothing could prepare me for the hurt of seeing my grandma rocking back and forth in agony, and yet being unable to hold her. Latex gloves are no substitute for human touch, and masks are an impossible thing to use when you’re crying.

“It was kind of more painful in a weird way, to be there in person with her, but not really be there,” my brother Nolan told me after.

While Ông’s passing wasn’t unexpected — he had ended dialysis 16 days before and the hospice nurses had stopped coming to prevent any potential spread of the virus — it didn’t make his death any easier.

The morticians took him away along with his favorite suit — something Bà insisted on so she could see him dressed up one last time — and were gone within minutes.

“He didn’t have corona, did he?” one of them asked before stepping inside the house.

That would be the last day Bà would spend in her old home. With Ông gone, she had no reason to stay. She took a bag of clothes and her medications to my parents’ place, where she’s lived for the last five months.

Bà wasn’t unaccustomed to moving or change. She spent the better part of her first 40 years on the run, but it was always with Ông at her side. This time she was alone.

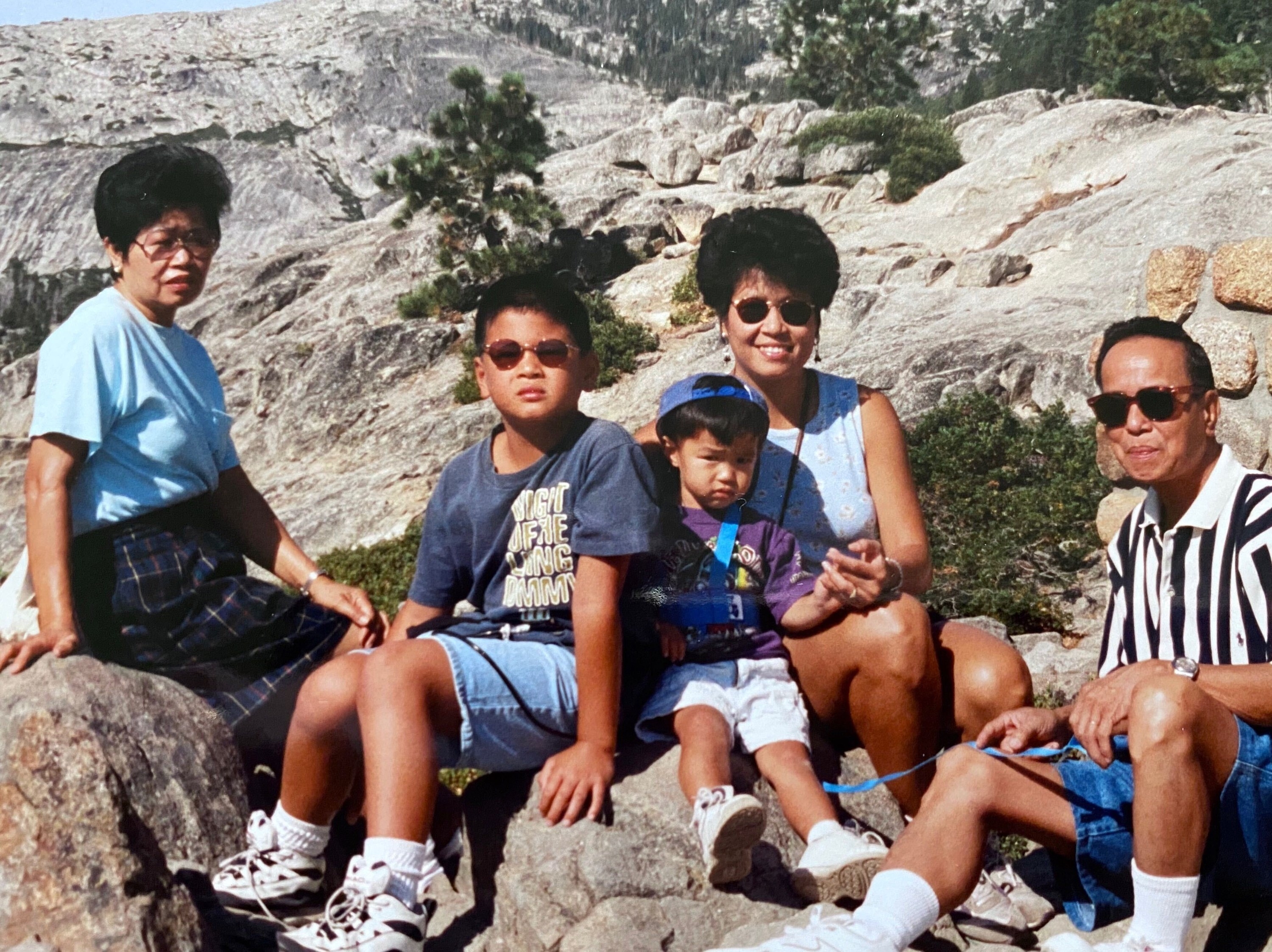

My Bà, who was born Nghiêm Thị Lệ Khanh, was the second oldest of 10 children born to a Hà Nội financier and a stay-at-home mother who moved their family to Sài Gòn in 1954, following a war that split the country into north and south.

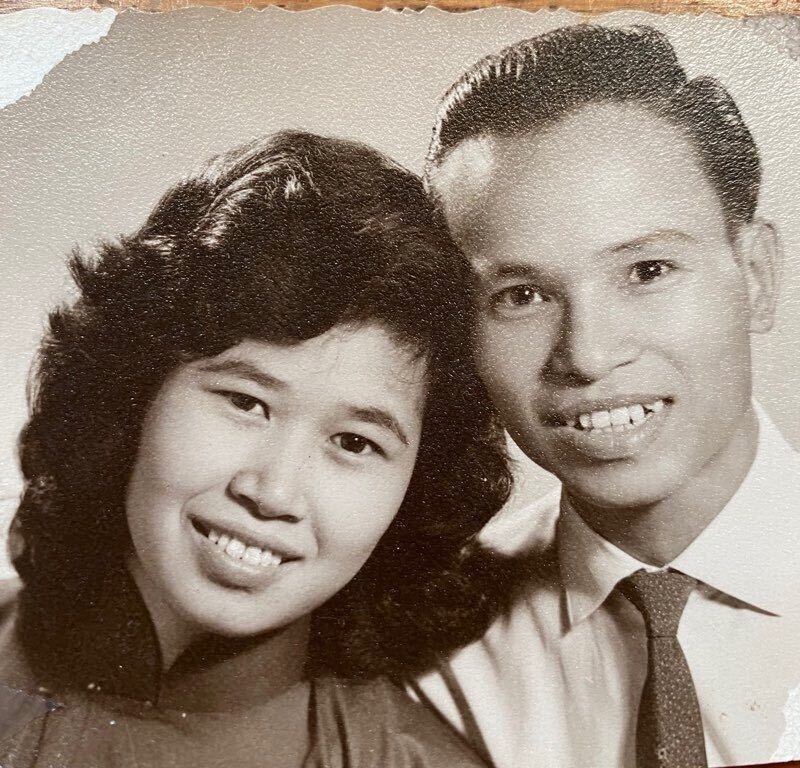

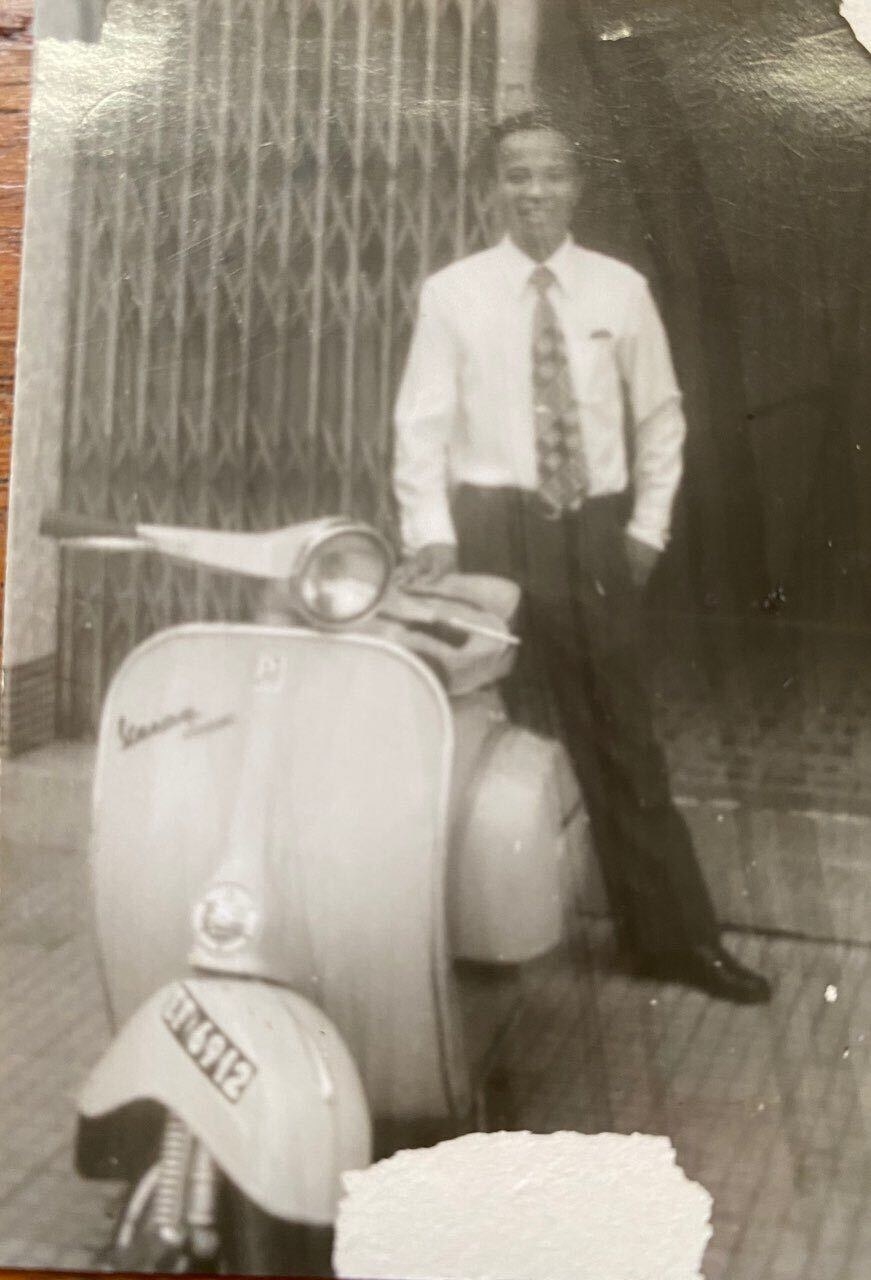

While she studied to be a teacher, Lệ Khanh, as the eldest daughter, was supposed to be the first married. She had met Nguyễn Đức Sâm — Ông, as I came to know him — the same year she arrived in Sài Gòn, but it wasn’t until four years later that they’d go on their first real date.

Lệ Khanh was intrigued by the former army medic who had fled the north after faking his own injury and deserting during a particularly vicious battle. He had started a printing business on the outskirts of Sài Gòn and came to help her father around their home when they needed him. Despite the objections of some of her family members (he wasn’t an intellectual, his complexion was too dark, he looked like a peasant, they complained), she got married to the nice man with slicked-back hair and French suits six years her senior in 1959. Hằng, their oldest child, was born the following year.

“He was a genuine, hardworking man,” Bà said, remembering her first impressions. “In those days, falling in love was not a thing. If you weren’t married by 25, you were considered an old maid.”

As war erupted again, they learned to love, building a family that went on to include three more children. Lệ Khanh taught cooking and home economics at a high school, while Sâm’s printing business flourished, allowing them to build a three-story home and carve out a middle-class life in Sài Gòn. It didn’t last long. The arrival of US troops and the push of the North Vietnamese into the South caused them to flee multiple times, to the point where they built tunnels under their home to escape.

By April 1975, as the Americans pulled out and Sài Gòn collapsed, there were few options left. The family knew Sâm, a deserter from the North Vietnamese army from the first war, was sure to be thrown in jail, so they fled. With nothing but gold bars sewed into the linings of their pants, the family of six boarded one of the last refugee boats out of the city, becoming some of the 1,500 people on a ship meant for 400.

“At one point, one of Ong’s brothers asked if they should leave the wives and children behind, but Dad refused to do that,” Hằng, my mother, remembered of a tense family meeting in the days before they departed. “‘Either we all leave together or we don’t leave at all,’ he said.”

Aboard a ship where each person was afforded a quarter of a cup of rice a day and barely enough room to lie down, the six held on as they floated across the Pacific to the Philippines and then to Guam, where they were transferred to a larger vessel. From there, they traveled to Fort Chaffee, Arkansas, and spent time in a refugee camp before finding a sponsor to take them all to Kansas City, Missouri, that September.

“I have a job, Mậu [his brother] has a job, we have our own very good homes, the children are all in very good schools,” Sâm told a local Kansas City newspaper on New Year’s Eve 1975 for a feature on his family. He had taken up a $2.75 per hour minimum wage job at a local printing press, and they eventually saved enough to buy a small craftsman home in the city’s north.

“We are all happy and very thankful to be here,” Sâm told the newspaper.

Lệ Khanh found their new world challenging to navigate. She had learned English in school, but pronouncing words like “water” made her self-conscious so she chose to write out her responses. When she arrived at her temporary home for the first time — their sponsoring family initially vacated their house and moved in with a neighboring couple to give her family a space for themselves — she was confused as to why the faucet had two handles. She had never lived in a home with hot water.

She also went to work, volunteering as a translator for the Red Cross to help put other immigrant families at ease, while taking paid sewing gigs at home and shifts as a restaurant line cook. And though she was Buddhist, she made sure to show up to the Presbyterian church every Sunday with at least two kids in tow out of respect for their sponsors.

After three and a half years of snow, my grandparents heard through friends that Vietnamese immigrants were congregating in a place called Orange County, California. They packed their bags and headed for the sunnier climate, bringing enough money to open a tailor shop that they would run for a decade.

Ông and Bà spent the rest of their lives together in Orange County, shuffling around but never straying too far from their children, who then had kids of their own. Now 45 years after turmoil in her home country forced her to upend everything, Bà is facing uncertainty all over again in the winter of her life.

This week, I spoke by phone with Ashwin Kotwal, a UCSF professor who co-led the study on loneliness and the pandemic and who has studied how the lives of those in palliative care and their caretakers have shifted over the last six months. I explained to him the tumultuous recent changes in Bà’s life and asked if it compared it to anything he’d been studying.

“The ways we’ve addressed grieving have been disrupted by this pandemic,” Kotwal told me, explaining that talking on the phone or over a video chat for some folks isn’t enough. “People like your grandmother are experiencing huge life events, like the transition into widowhood. Just getting an app is not going to do it.”

Some groups, Kotwal said, have actually done better during the pandemic. Social isolation, the physical separation from others, doesn’t necessarily lead to loneliness, the mental state of feeling alone or unable to communicate with others. In some cases, the isolation has actually meant that some people have turned to regular phone calls or Zoom meetings to check in with loved ones, leading to steadier relationships.

“People like your grandmother are experiencing huge life events, like the transition into widowhood. Just getting an app is not going to do it.”

But other groups in the UCSF study, particularly those experiencing a traumatic life event like widowhood or moving to a new community — both of which Bà is going through — showed no sign of becoming less lonely. “When I’ve seen these types of situations, people who are newly widowed and after serving a huge caregiving process for their spouse,” Kotwal said, "it’s a huge part of their life and gives them routine and structure and meaning, and suddenly that’s lost.”

For the last six years, Bà had taken Ông to practically every doctor’s appointment and hospital visit. She cooked for him and carefully measured out his medications every day. When he was tired, she carried him up and down the stairs from their bedroom to the living room couch. It taxed her, but there was purpose. When we talked about it, she played it off as some innate duty, something that wasn’t even a question.

Losing that purpose is painful, said Kotwal. When compounded by a pandemic that eliminates the ways you can grieve or lean on others, it can be demoralizing.

Ông’s “funeral” on April 14 was just that: crushing. Those of us who could come — immediate family including three of his four children, their spouses, and three grandchildren — wore black, and used paper clips to fasten a piece of black fabric, a Vietnamese memorial symbol, to our tops. There were also masks, latex gloves, and hand sanitizer.

Initially, the funeral home director said there could be 50 people in a large hall. Then with new regulations, it was reduced 20. By the time the date came, we were only allowed four people at a time in a 225-square-foot room for a total of 30 minutes. Ông’s older brother, who had accompanied him on practically every step of the way from Vietnam, didn’t come, afraid that stepping outside his home would make him susceptible to the virus. He had said his last goodbye over FaceTime a few days before Ông’s death.

Bà stayed in the funeral room as we rotated in and out. In lieu of picture frames or anything else in the room other than a Buddhist offering of fruit and Ông’s favorite foods, photos of our family were stuffed into the crevices of the coffin, which remained closed. The mortuary hadn’t handled the body as they would have before the pandemic, and the suit Bà had hoped to see Ông in again one last time lay atop him under the lid. This wasn’t how she had imagined it.

Thirty minutes in and out. No kisses. No embraces.

“How can you have a proper goodbye with these kinds of conditions?” my brother Nolan asked.

I allowed myself one passing rub of Bà’s shoulders. But it should never have been like this.

Bà is slowly warming up to living with my parents. She’s transformed their garden and spends some of the day bickering with her daughter, as I would with my mom. The reflection is sort of endearing.

Like all of us, she is slowly finding her new normal. She’s sewing masks in her spare time, and made me five out of a fabric with cartoon bears for my birthday. She also has a new iPhone and is learning how to use YouTube and FaceTime. It’s been a work in progress, and butt-dials have been a semi-regular occurrence. (“Ba fat fingers,” she texted me last weekend after one of her mistaken calls.)

On a humid August day during my last visit home, I rolled out of bed to see Bà carrying a large spiky fruit the size of a beach ball. She smiled, putting the 28-pound jackfruit on an outside table so that my mom could break it down using a meat cleaver and a hammer. They spent the morning disassembling it and storing its innards in ziplock bags.

Bà didn’t seem to care much about the fruit. She’s eaten it for years, and when it was packed, there was only a little left for our household. Instead, she told me, we’d be taking it to the relatives in Westminster whom she hasn’t seen in months. I drove her there, masks on, with the windows rolled down.

We stopped at her neighbor’s house, where, at a distance, Bà traded her jackfruit for a new plant that could be potted in the back of my parents’ home. They talked about the last three months, their children, and Bà’s grandchildren. Then we stopped at her old home, where she dropped off some fruit for my aunt, who still lives there with her husband.

It was the first time she’d been back since moving her belongings out after Ông died. I could see the pain flood back. She sat on the front stoop, arms wrapped around her knees, rocking for nearly five minutes.

Eventually, though, she stood up. There were more deliveries to make and she didn’t want the fruit to go bad. ●