BARCELONA — Marta Rosique woke up on the morning of the Catalan referendum at 6 a.m. She had spent the night at the University of Barcelona in case Spanish police officers tried to stop the students organizing there. Rosique and around 50 other student-activists were ready to defend the university if the police came in.

In the days leading up to the vote, Catalan separatists and the Spanish government were locked in a game of cat and mouse. The Catalans were set on holding a referendum on Oct. 1 to decide whether they wanted to become independent from Spain. The Spanish government was set on stopping them. Spain's constitutional court declared the referendum illegal and sent thousands of Civil Guard national police officers and riot police into the region to shut it down.

The violence that day was intense, with reports estimating more than 900 people injured in the ensuing police crackdown. Pictures and videos of police brutality flooded social media and shocked the world. Many Catalans made it to the impromptu polling stations, though, with almost 3 million votes cast. They also found ingenious ways to hide their ballot boxes with games of dominoes, fake weddings, and church services. By early Monday, officials were saying that 90% of the votes were cast in favor of independence.

On top of the physical violence, the Spanish government was also fighting an information war, with the Catalans trying to publish polling information online. The Spanish government was accused of shutting down Catalan government websites on Oct. 1.

This is the story of how a group of young activists organized the day of the referendum — rapidly spreading information across chat apps and social media. It reveals how Rosique and her pro-independence student organization, Universities For Republic, jerry-rigged their phones together to stay one step ahead of the Spanish government. They hastily connected chat applications like WhatsApp, Telegram, and Signal — creating a digital whisper network of young Catalans quickly relocating polling stations, tracking Spanish police activity, and coordinating with an assembly of local firefighters.

And Rosique said all of that was thanks to some advice they received from Julian Assange.

“We connected online with Julian Assange and Wikileaks and he told us some of the apps we could use,” Rosique told BuzzFeed News. The 21-year-old journalism student said her organization emailed Assange a few weeks before the referendum. Assange responded with a video, a clip of which he tweeted — complete with Catalan subtitles — on Sept. 27.

“This was before the referendum happened,” she said. “We asked him what could we use that the government couldn’t control and one thing that he said was that if everyone uses the same app then the Spanish government will try and control this app. So it's better to diversify and use other apps that might be more secure.”

Their main apps of choice were WhatsApp, Telegram, and Twitter. The students based out of the University of Barcelona spent the day trying to organize the digital chaos happening across these platforms by setting up an information center on campus where Catalans — especially senior citizens who weren’t able to navigate chat apps like WhatsApp or Telegram — could come and get polling information as it changed throughout the day.

Here’s how the Catalan chat network works.

Each polling station had its own WhatsApp group. These groups would then connect with student activists and report back to the information center at the university. At the beginning of the day, this worked well, but Rosique said that as voting got underway, mainly of the groups were compromised by Spanish nationalist trolls.

“There were a lot of WhatsApp groups created, but for example, in the WhatsApp group of my polling station, some people for the unity of Spain entered into the group and they started sending messages and changing the name of the WhatsApp group and started disrupting it,” she said.

As more groups were getting clogged up with trolls, rumors started swirling that WhatsApp was being spied on by the Spanish government. Then the polling websites began to fail. Spanish media reported that internet connections at polling centers were being disrupted — sometimes physically by police.

After that, many Catalans moved to Telegram, a chat app similar to WhatsApp, and switched tactics. Two referendum-themed chatbots had been set up for voters and were being shared across Catalan social media. A few days prior to the vote, the vice president of Catalonia, Oriol Junqueras, had tweeted instructions on how to use them.

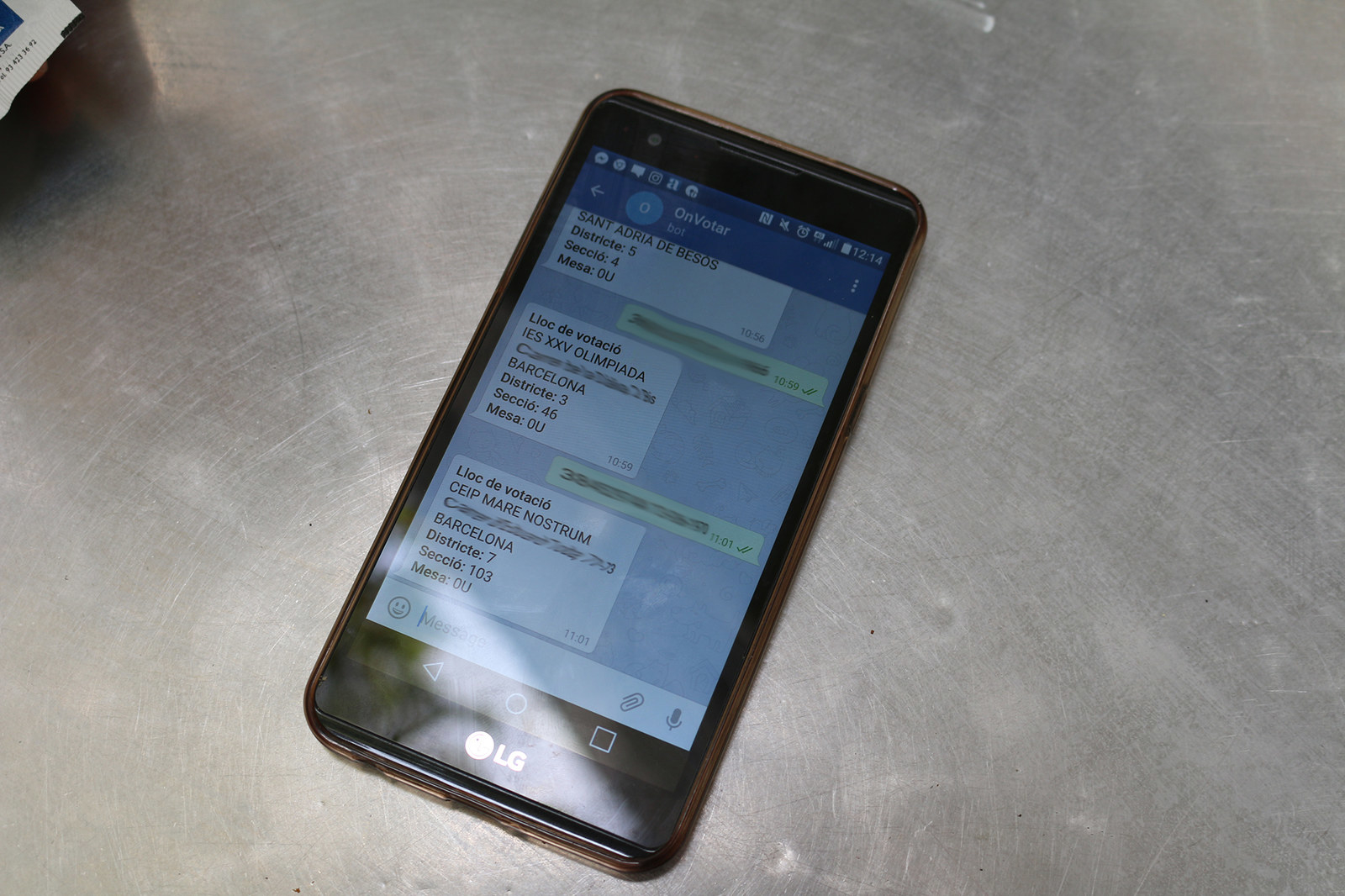

“What the Catalan government did or — I don't know if some individuals did it or the Catalan government — they created a bot where you could just write your ID and your birthdate and that way you could know where you had to vote,” Rosique said of the polling information app, called OnVotar. “There was another bot that was called Alerts 1O, which basically explained everything that was happening at the moment. So we could know which polling stations needed more people to defend them, and also knew where the Spanish police was repressing us.”

The Alerts 1O bot is still active. It transmits short pro-independence push alerts. These alerts get screenshot and make their way into WhatsApp groups or out onto more public social networks like Facebook and Twitter.

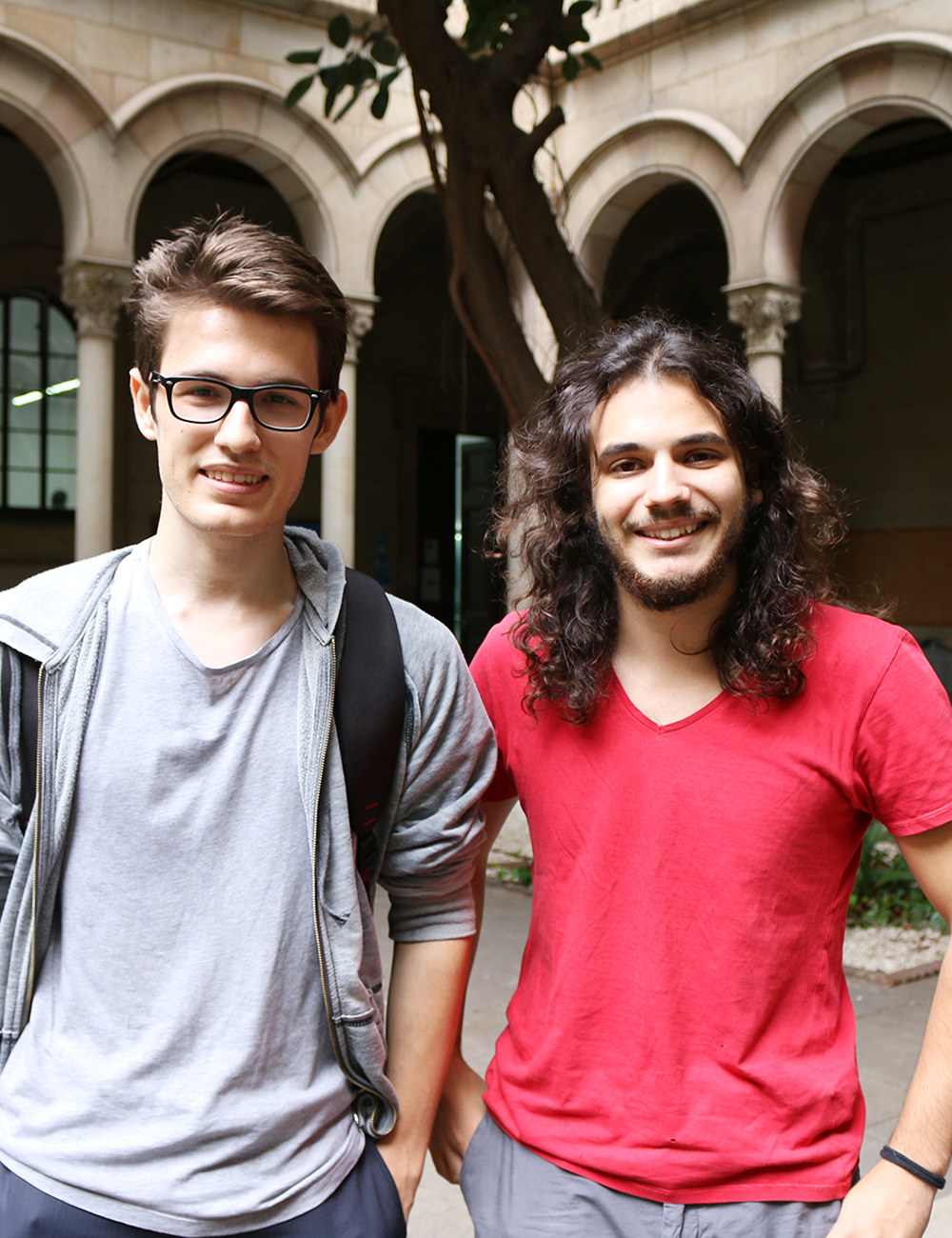

A 20-year-old University of Barcelona named Bertran told BuzzFeed News that he knew where to vote because of the Telegram chatbot.

“I found a polling place with the internet. I found it on Telegram. It was a chatbot you could ask on Telegram,” he said. “I also saw a lot of stuff of on Facebook.”

Another University of Barcelona student named Carlos, 19, told BuzzFeed News that he was only able to cast his vote because of his phone.

“On the day of the voting, there were lots of sudden changes in the organization. Some polling stations were shut off and you had to move to another place and through social media or iPhones or whatever you could stay always in contact with everybody and know where you had to vote,” he said. “For example, in our case, we stayed all day long in the polling station in order to protect it from the police. Because we didn't know if the police were coming or not and we organized all of that with our phones.”

Tracking police activity was one of the largest priorities for the Catalan activists on the day of the vote. A user-generated map quickly started getting shared around. “There was a map, a Google map, with points where the police had been and you could see different colors. I don't know who made it,” Rosique said.

One of the key moments in the lead-up to the referendum came about a week before the vote, when Catalan Twitter users found the location of two chartered ocean liners currently docked in Barcelona’s port that Spanish police have been using as a command center to house thousands of officers.

In a weird twist, one of the requisitioned boats happened to be a cruise ship adorned with a large picture of the Loony Tunes character Tweety Bird, or Piolín as he’s called in Spanish. A satirical #FreePiolín hashtag started going viral in Spain. The lighthearted hashtag was also the beginning of a kind of epiphany for Catalans: They could use social media to monitor the police.

“The Tweety Bird has also become an image of repression. There are T-shirts created. People have been using it all over as an image of being against repression,” Rosique said.

As the police violence began on Sunday, graphic photos and videos went viral, first within Catalonia, then within Spain, and then internationally.

A 19-year-old university student named Marcel told BuzzFeed News that he thinks the ability to record the Spanish police attacking voters drove more Catalans to vote for independence.

“I know a lot of people, quite a few who were going to vote white — not vote against it [but leave their ballot blank out of protest] — but saw those images and went and voted yes,” he said. “That made them realize they didn't want to be part of a state like that.” Ahead of the referendum, polling had suggested that most Catalans wanted the right to vote but that a slender majority were in fact opposed to independence.

Another University of Barcelona student called Nina, 19, told BuzzFeed News that the viral videos Catalans were seeing on their phones were also completely counter to what they were seeing on Spanish television. “On the Spanish TV, they were saying that they were doing the right thing,” she said, “but here you saw things going bad.”

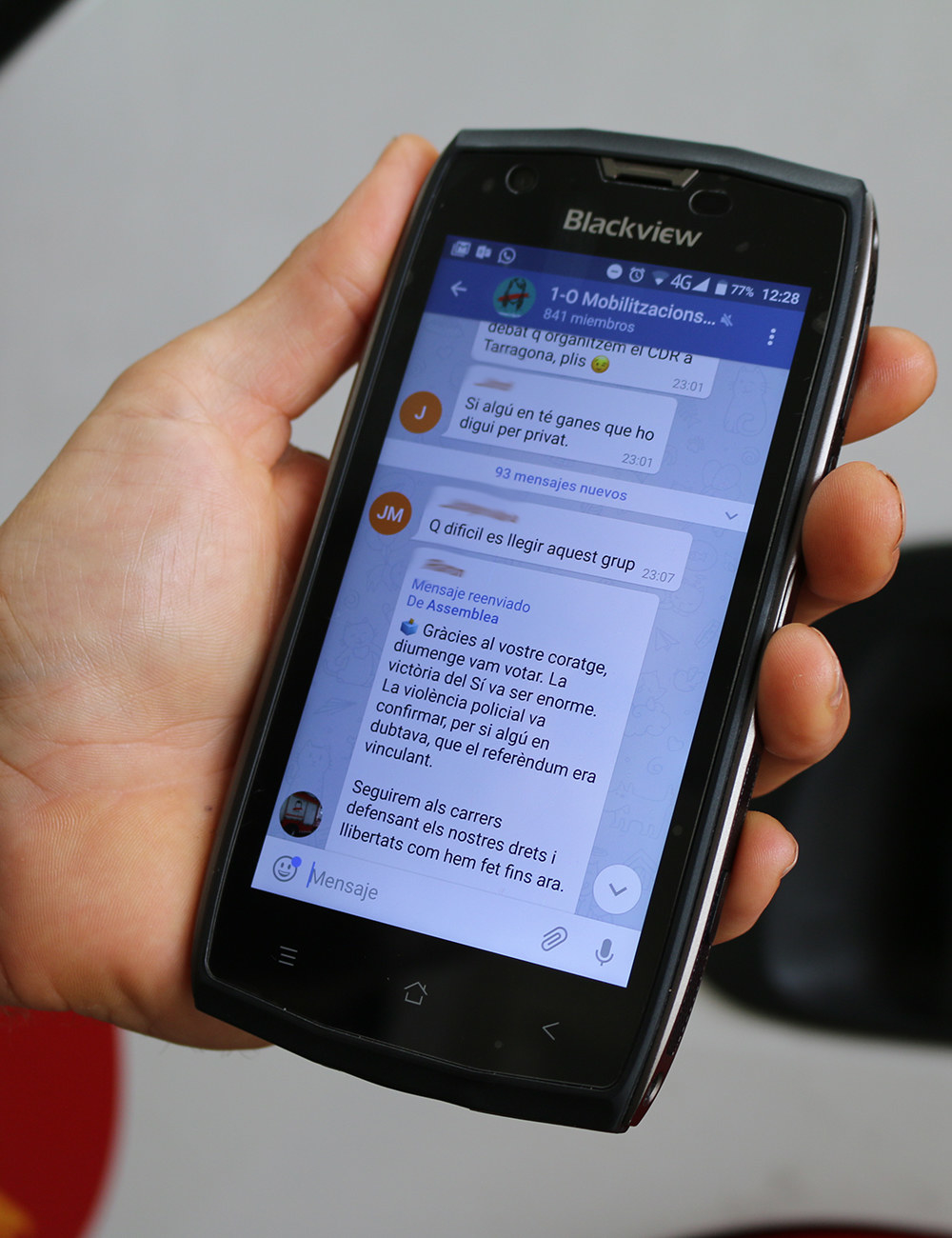

One of the images that has struck the biggest chord around the world has been the photos and videos of Catalan firefighters creating a blockade between Spanish police and protesters. And it turns out that Catalonia’s firefighters were also using Telegram to mobilize — and were in direct communication with Rosique and the student-activists.

“During the weeks before the referendum we had many mobilizations of students and we were always in contact with the firefighters and they would come with us, as well,” Rosique said. “They were always showing their support.”

Rosique said that the students had the numbers to mobilize, but they wanted to make sure the pro-independence demonstrations remained peaceful and civil.

“We have the ability to mobilize people, but they [the firefighters] have the ability to bring safety to everything, so we tried to combine our powers, let's say,” she said. “People really trust firefighters. It's always been this way and now they are trusting them a lot more.”

Victor Dobaño, a fire chief for the Barcelona Fire Department, excitedly showed BuzzFeed News the Telegram group Catalan firefighters have been communicating with.

“When I connected, we had 400 people. And now, it's up to 800. But it's only for firemen thinking about the independence movement,” Dobaño said. “We’re using this for the logistics of organizing across all of Catalonia.”

Dobaño wanted to make it clear that the firefighters’ involvement in the pro-independence movement is not something they do while they’re at work. He said that all the videos of Catalan firefighters protecting the pro-independence voters were taken outside of work hours. “They take their helmets and their jackets and go to the streets,” he said.

“The position of the firemen is neutral. All we want is peace and not violence,” Dobaño said. “I want people to not feel alone. We wanted to do a symbolic thing to let people know that they are not alone, that we are with them.”

Juan Xalmet, a firefighter who was born in Valencia and is not Catalan, said he’s not sure how he feels about the independence movement, and believes that it would be dangerous for firefighters to advocate for one side over the other.

“For me we are working for the people — and the politics are another thing. For example, all the people condemn all the violence, but we are supposed to help the people. Not to say in one way or another way for political ideas,” he said. “For me, we are here to help the people.”

The Catalan president, Carles Puigdemont, is expected to formally declare independence on Oct. 10. But there are rumors that if Catalans don’t back down, Spain may invoke Article 155 of its constitution, which would essentially allow the Spanish government to bring the military into Catalonia and take back control of the region. The Spanish prime minister, Mariano Rajoy, told El País newspaper he had not ruled out the idea of suspending Catalonia's regional autonomy.

Pro-independence activists like Rosique aren’t expecting an easy road.

“Catalan identity has been very important to me,” she said. “For us, having independence is about breaking with the regime that we've been living in, a regime that keeps being very fascist and that hasn't changed much since the dictatorship [of Francisco Franco, who died in 1975] and although that they call it a democracy, they are showing now in a very clear way that this is not a democracy that we are living in.”

Rosique also believes that the playbook young Catalans spontaneously assembled — with some help from Assange — during the referendum will continue to evolve in the weeks and months ahead. She believes that the recent progress toward independence is partly thanks to social media, but hesitates to compare it to something like the Arab Spring.

She thinks people are starting to embrace more secure, private apps to organize politically. She said that WhatsApp, Telegram, and Twitter may have worked well thus far, but expects that while the strategy of decentralized social media will stay the same, their tool kit might change. She said that in the last week or so the number of people in Catalonia downloading another encrypted chat application called Signal has spiked.

Rosique’s view of where social media is heading isn’t all that different from her view about where Catalonia is heading. “It’s what’s happening. It’s the way that we’re going now. A more decentralized way, more networks that put the people as a center, not the interests of the companies.”