SÃO PAULO, Brazil — A rumor circulating across WhatsApp this weekend had a warning for supporters of Brazil's far-right presidential candidate, Jair Bolsonaro: Show up to the polling stations wearing any sort of merchandise with his name or face on it, and you will be turned away and unable to vote. This, you see, was part of a coup organized by Brazil's electoral commission, which doesn't want Bolsonaro to win. Of course, none of this was true, but that didn't stop it from being one of the most shared pieces of content in public groups on WhatsApp in Brazil.

Facebook's penetration in Brazil is undoubtably massive, ranked third in the world, behind India and the US. But WhatsApp, the messaging service also owned by Facebook, is the true beating heart of the internet here. According to a study in 2016, nearly 100% of internet users in Brazil have WhatsApp. That means about 40% of the country's 207 million people are using the app.

WhatsApp is also a nightmare for fact-checkers. Nieman Lab called it a "black box of viral misinformation." Brazil's political activists, especially on the far right, have been extremely aggressive about using it to organize. Last year, Movimento Brasil Livre (MBL), or “Free Brazil Movement,” a right-wing pro-Bolsonaro youth movement, was the subject of an investigation by one of the country's biggest papers, which reported from inside one of their WhatsApp groups. The paper discovered that MBL was using WhatsApp groups like "MBL merchants" or "MBL lawyers" to spread their content — including rumors and fake news. BuzzFeed News has reached out to MBL for comment.

Due to WhatsApp’s encrypted messaging structure and the peer-to-peer nature of it, it’s impossible to know what people are sharing or how frequently. But if a WhatsApp monitor built by local fact-checking group Eleições Sem Fake is any indication, it looks just as overrun with misinformation as Facebook is.

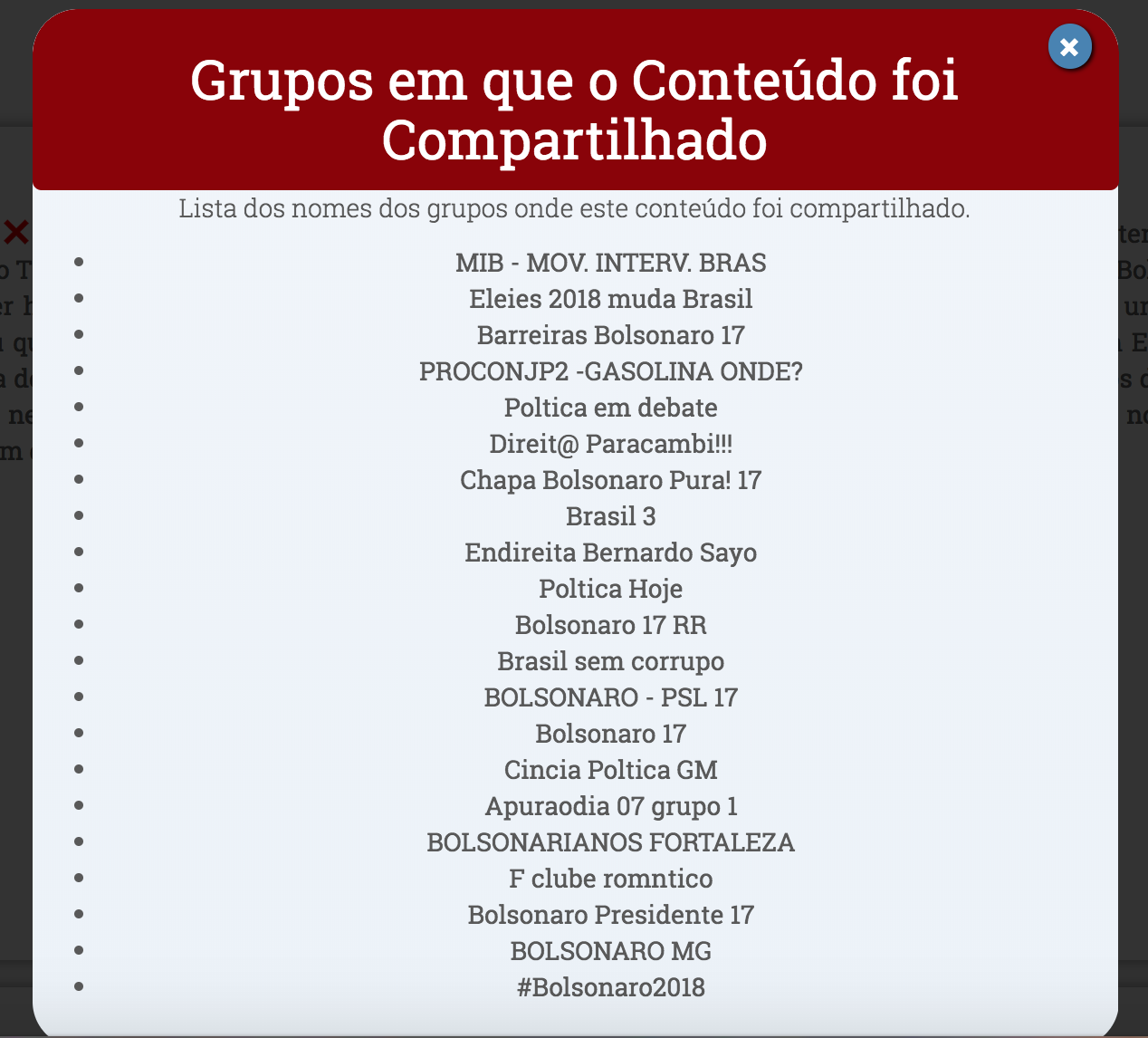

Fabrício Benevenuto, an associate professor of computer science at the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, and creator of the WhatsApp Monitor, told BuzzFeed News that the tool gathers data across 350 politically motivated WhatsApp groups. It pulls in images, videos, audio files, links, and text posts.

Benevenuto said that attempting to track misinformation on WhatsApp has been extremely hard, due to the social network's encryption, but he said the fake news his monitor collected became increasing politicized as the election drew closer.

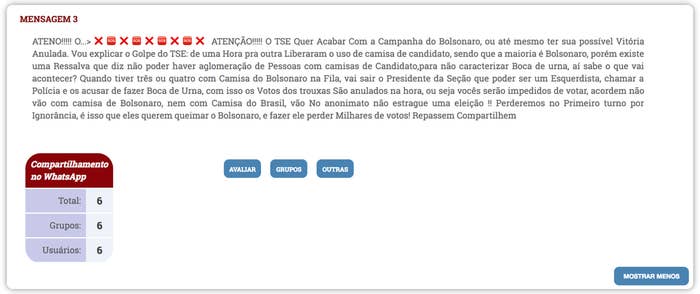

Over the weekend, the monitor was able to record groups sharing the rumor that Bolsonaro supporters would be turned away from polling stations if they wore any merchandise supporting the candidate. On both Saturday and Sunday, several versions of the rumor were among the top five most shared posts across the 350 public groups.

"We don't know the extent to which public groups represent private groups," Benevenuto said. "It is reasonable to assume that a malicious misinformation campaign might attempt to maximize the audience of a fake story by sharing it in existing public groups. So, we believe these groups are the front door for misinformation to reach the private groups."

Aimee Rinehart, who works with First Draft, an international group of researchers and journalists who fight digital misinformation, said the tricky thing about WhatsApp is no one actually knows what's happening inside of private groups.

"What we do know is that people trust the information they see in a WhatsApp group and are more likely to read every message that comes into the platform, unlike Facebook where you skip many posts because of likes/dislikes," Rinehart said.

Moderating WhatsApp isn't impossible. Since May, WhatsApp misinformation has contributed to 17 different lynching incidents across India. One event completely destroyed a village. Over the summer, during the Karnataka state elections in India, WhatsApp detected and banned a number of accounts that were engaged in spam-like behavior. And in a September blog post, Mark Zuckerberg wrote that WhatsApp and Facebook's moderators coordinate on banning malicious users.

"Our systems are shared, so when we find bad actors on Facebook, we can also remove accounts linked to them on Instagram and WhatsApp as well," he wrote.

In Brazil, WhatsApp is working closely with a local fact-checking service called Comprova, the first fact-checking group to use the WhatsApp Business API to scan for misinformation. But this access still doesn't give journalists or researchers a clearer idea of what is being shared in or between family or friend groups.

Much has been made of Facebook's efforts to combat misinformation on their platform in the lead-up to Brazil's national elections earlier this month. In July, Facebook deactivated 196 pages and 87 accounts in Brazil for their part in “a coordinated network that hid behind fake Facebook accounts and misled people about the nature and origin of its content, all for the purpose of sowing division and spreading misinformation.”

Facebook didn't publicly disclose any specifics about the pages and profiles deactivated in their pre-election purge, but senior organizers from the pro-Bolsonaro youth movement, MBL, confirmed on Twitter that many of their pages were affected. And while it appears that Facebook was able to successfully neuter some large constellations within Brazil's solar system of hyper-partisan Facebook pages, what isn't clear is what effect that has had on WhatsApp.

Rinehart also points out that in Brazil, Facebook and WhatsApp are much more intricately linked, both technologically and culturally. Many posts on the newsfeed have a button underneath them that allows you to instantly share them to WhatsApp.

"Closed messaging apps like WhatsApp are definitely concerning," Rinehart said. "It would be ideal for Facebook to end the easy share button from Facebook to WhatsApp, or at least have the surrounding content travel with it to provide context."

This connection between WhatsApp and Facebook was seen over the weekend as the polling center rumor spread. A quick search showed that many users were copying and pasting the WhatsApp message into Facebook and vice versa. And, really driving home the interconnectedness of WhatsApp and Facebook, the most shared WhatsApp post on Friday was just a link to a Facebook video made by Roberto Motta, the founder of The New Party, asking people to vote for Bolsonaro.

The Bolsonaro voter rumor itself has connections to a wider suspicion of electoral fraud that spread across public social networks like Twitter and Facebook on Sunday. A video surfaced Sunday afternoon of a voter trying to type in a number for a presidential candidate on a voting machine only to have it immediately change their vote to one for Fernando Haddad, the candidate of Brazil's leftist, populist former president Lula da Silva and his Workers’ Party (PT). The video originated on Facebook and was first shared by a user named Lucas Andressa.

Local Brazilian media immediately debunked the video. But that didn't stop it from being shared by thousands of people — including Bolsonaro's own sons.

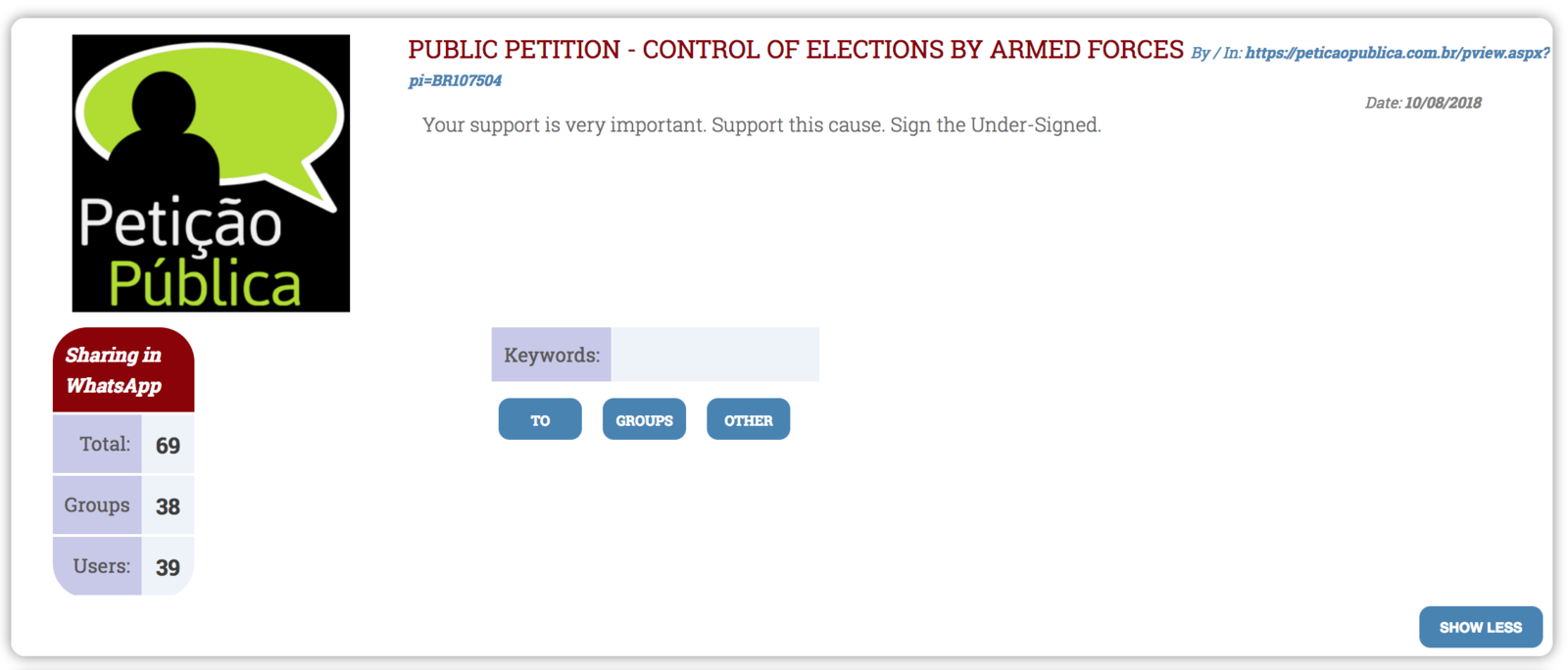

The next round of voting isn't shaping up to be much better as far as WhatsApp's influence is concerned. On Monday, the most shared item on the public WhatsApp groups was a petition for the military to inspect the second round of votes on October 28.