On Wednesday, Tencent, a Chinese tech giant best known for its super-popular messaging app WeChat, found itself at the center of a frenzy. Screenshots began to circulate of the company’s "Epidemic Situation Tracker," which tracks the coronavirus’s spread in mainland China, displaying a death toll almost 80 times higher than the official number. This time was reportedly the third instance the tracker briefly displayed numbers much higher than the official counts coming out of Beijing.

Adding to the alarm, the numbers matched a viral WeChat rumor that spread separately across Chinese and American social media. (In actuality, the coronavirus outbreak has killed 565 people and grown to more than 28,000 cases, according to the World Health Organization, with 265 outside of China.)

A spokesperson for Tencent told BuzzFeed News the screenshots were fake: “Unfortunately, several social media sources have circulated doctored images of our ‘Epidemic Situation Tracker’ featuring false information which we never published,” the spokesperson said. “Tencent does not condone the dissemination of inaccurate information and fake news especially during this sensitive period. We reserve all legal rights and remedies in this matter.”

China's censorship laws, which far predate the first coronavirus cases in the city of Wuhan late last year, have been deployed under the pretense of preventing mass panic. But it has still been a constant struggle for China's government to control the narrative around the outbreak.

On Thursday, Chinese state media reported via Weibo, a Twitter-like social platform, that Dr. Li Wenliang died after contracting the coronavirus, only to report hours later that he was alive but in critical condition. Li was then declared dead hours later on Thursday night.

"We deeply regret and mourn this," hospital staff wrote on Weibo.

Li, who contracted the virus while treating patients, was one of the eight whistleblowers initially arrested by local police in Wuhan, China, last month for "spreading rumors” about the outbreak. There are reports that up to 40 other people have been investigated for similar charges across the country.

The reaction to Li’s death on platforms like Weibo and WeChat has been intense. “I’ve never seen such collective anger and sadness on my WeChat feed,” journalist Viola Zhou tweeted.

But even as Li became a hero on Chinese social media, the enforcement of anti-misinformation laws like the one used to arrest him is becoming common across Asia.

In the last month, three people were arrested in Kerala, India, on allegations of “spreading fake news,” two people were arrested for purportedly sharing “false information" in Bangkok, and five people were arrested for similar charges in cities across Malaysia.

This week, Hong Kong police arrested a mall security guard for the alleged “transmission of false message[s] by telecommunication," accusing the 37-year-old man of causing panic by sharing an audio file on WhatsApp that claimed five mall staffers had called in sick with a fever. The arrest did little to quell rumors, because following it, Hong Kong police bragged about arresting the man on Facebook. Unlike the rest of China, Hong Kong has no "fake news" law, but it does have a law dating back to 1935 against using a phone to send false messages to cause annoyance, inconvenience, or needless anxiety.

But people in China are still using the internet to track the outbreak. The problem is: If they amplify the wrong thing, they could get arrested.

Yuan Xiaohui, the CEO of Beijing-based tech company QuantUrban, is trying to create a useful coronavirus crowdsourcing service while avoiding rumors.

“To prevent arousing panic, we only add government publicly released data. All of the data comes from [the] Health Commission of the related city,” Yuan told BuzzFeed News.

QuantUrban combines preexisting map data of Chinese cities with reports from volunteers along with outbreak data that comes from cities’ health commissions. So far, it shows infection cases for 23 cities, including Beijing, and a timeline of daily changes. To minimize the possible accusations that a live, hyperlocal heat map of coronavirus cases could cause alarm, there’s a warning on its website that reads “don’t panic.”

“Some users of our websites will give us feedback when [a] certain place is mistakenly or not accurately annotated, then we will correct it and update the website,” Yuan said.

Hong Kong's government has the almost impossible task of navigating between the CCP’s coronavirus plan and a pro-democracy protest movement now entering its eighth month. The city government has demanded more transparent and proactive containment measures and has been accused by users on pro-democracy social networks like Reddit and LIHKG of downplaying the outbreak’s seriousness and putting its citizens in danger to appease the government in Beijing. Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam has resisted a total border closure, instead enacting quarantines for mainland Chinese travelers entering Hong Kong.

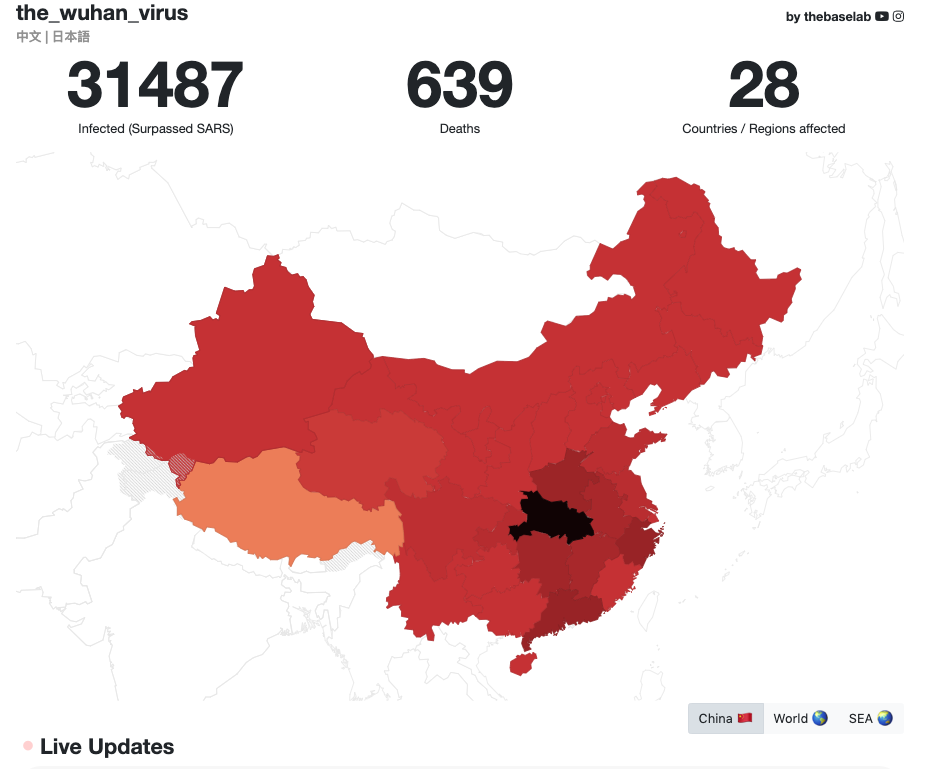

As the city’s officials continue to walk a difficult path, a group of high school students in the city, working under the name thebaselab, went viral after building a coronavirus tracker similar to the one on the other side of the Great Firewall, China’s heavily restricted internet.

“The live map idea is inspired by [the] mainland's websites on the coronavirus by Tencent and other tech corporations,” Ken Chung, the map’s developer, told BuzzFeed News. “Those are huge sites with large teams behind them, and really popular among mainlanders. But they were only in Simplified Chinese and mostly report local official news and numbers.”

Thebaselab’s live map works in three languages and has been shared several thousand times on Facebook and Reddit since it launched last month.

Chung said that Beijing’s inability to control the flow of information about the outbreak will be a huge wake-up call for Chinese users.

“I think arresting someone just because they posted inaccurate information is plain ridiculous. While I do agree there's a certain responsibility borne when posting stuff online, it's really impossible to draw a line between misinformation and non-government approved content,” Chung said. “While the Chinese have just noticed the harsh truth of censorship, I don't see why Hong Kongers should step back and accept it.”

“While the Chinese have just noticed the harsh truth of censorship, I don't see why Hong Kongers should step back and accept it.”

The live map is only half of thebaselab’s coronavirus work. The team members also run a WhatsApp group chat called GloNews Room, which they recently gave BuzzFeed News access to. It’s primarily run by thebaselab member Andy Tang.

“Since the Wuhan virus outbreak happened in Wuhan, China, I have been following different Chinese media reports and social platforms as the Beijing government tries to lock down the free flow of information,” Tang told BuzzFeed News. “Eventually it turned into a global emergency issue, and it would be our job to deliver instant reports from countries abroad.”

GloNews Room has about 100 users, who collect, vet, and disseminate coronavirus news, but the group doesn't always focus on the virus. A bunch of the members also used the group to share memes about US President Donald Trump’s State of the Union address earlier this week.

Tang said that while crowdsourcing can make things more confusing, it’s also the best way in the current information ecosystem to deal with the sheer scale of the global news cycle.

“Crowdsourcing is providing an all-round perspective for netizens to fact-check the authenticity of a large amount of information,” he said. “Which is now critical under this chaotic environment with all sorts of rumors floating around.”