For about a year, a Twitter account named Beto’s Spotify would tweet songs Beto O’Rourke might be listening to — an ironic parody run by a supporter of the candidate's.

The day O’Rourke dropped out of the presidential race, unexpectedly and late on a Friday, the account broke from the norm: “Y’all, what do we do now.” A few days later, another tweet appeared: “i thought i’d gotten over beto dropping out. but i just dyed my hair black so, maybe i’m not over it yet.”

Candidates' superfans, or stans, have become ubiquitous on Twitter — a new daily part of doing business in politics. People build fandoms around everything from sets of policies to how many languages a candidate can work into a press gaggle. And once the stans settle in, they’re defending their candidate from any slight, especially criticism from other candidates’ fans. Each day might bring a battle between different factions, or send a deluge of intense criticism toward a single person in politics or media. And unlike pop culture, where the musicians don't stop their campaigns, when candidates like O’Rourke or Kamala Harris end their candidacies, the fandom comes to a sudden halt. The dynamic can turn especially toxic — with stans, the media, and all kinds of users picking through the reasons for the failed bid, and the candidate’s most dedicated supporters can be on the receiving end of taunting and recruitment from opposing candidates’ stans.

“When he announced that he was dropping out, I think all of us were just shocked, it happened so suddenly that we didn’t even have time to react,” said Alyssa, the 19-year-old from North Dakota behind Beto’s Spotify. “Especially since, for a lot of us, he was the only one we really were rooting for.”

At first, “I didn’t believe it actually,” said Jade, a 25-year-old Harris supporter in Tennessee who didn’t want to share her last name because she'd made an anonymous Twitter account. “People are really devastated, a lot of the #KHive are women of color,” she added, referencing the hashtag of Harris’s most fervent and active supporters. “A lot of us have said that this is the first time that many of us have cried about something politics-related since Hillary lost.”

Gregory Truman, a data scientist from New Jersey and active #KHive member, alluded to anger felt within the community about coverage of the candidate, referencing recent Politico and New York Times reporting on Harris’s struggles. “We tried to scramble to try to find out, and because a lot of us are active in volunteering,” he said, “we got a message from the organizers and we were sad, we were mad, and we were frustrated.

“I wish I’d had the opportunity to vote for a black woman for president.”

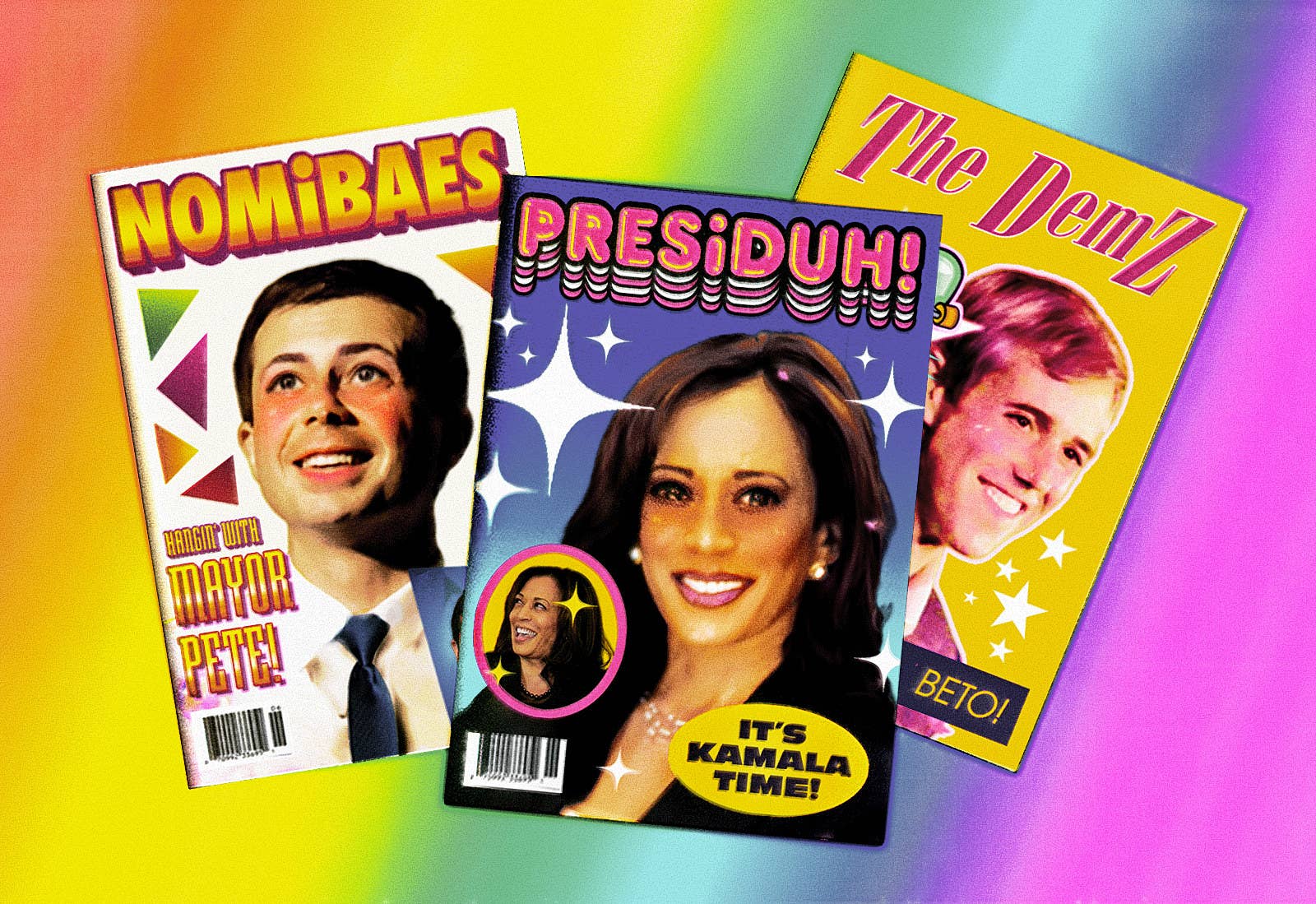

Politics Twitter and Stan Twitter have always been intense, niche corners of the internet — but this presidential primary has converged the two and spit out tribes of supporters that are willing to go off on the internet for their candidates, spawning free rapid-response communication teams and wins/nightmares for campaign staffers across the board. Search nearly any of the presidential candidates' names and you’ll find an online community crowning Elizabeth Warren their “qween,” and praying for the chance that the random phone number calling them just might be the senator thanking them for a donation and not a robocall for an insurance policy for a car they don’t even own; people tweeting That One Tweet about O’Rourke and mourning his campaign when it ended abruptly; the #KHive making a video of Harris in a sparkling rhinestone jacket go viral and vehemently defending their candidate online.

The 2020 election has, in fact, turned Twitter into a breathing, combustible ecosystem of warring factions — where the struggling O’Rourke and Harris pulled in as devoted, enthusiastic, and vicious supporters as the ascendant Pete Buttigieg and steady Bernie Sanders, and where the real people mixed up in all of it can get lost in the rush.

But everyone is watching what happens on Twitter, where press narratives take shape.

The relationship has become symbiotic. When I talked to stans, they told me about their interactions with campaign staffers who solicited their feedback. When I talked to campaign staffers, they sometimes spoke warily about off-the-rails grassroots campaigns and urged that they couldn’t control everything their fans do online. But everyone is watching what happens on Twitter, where press narratives take shape.

“Sometimes there will be a legitimate person, or reporter, or pundit who tweets something out, and Kamala’s team can only go so far in how sharp they can be in their responses, so I think we’ve taken it upon ourselves to help correct the record,” said Chris Evans, who turned his large Twitter following into a soundboard for Harris supporters. “So sometimes I’ll quote-tweet something … and a lot of the people that follow me see it, and they’ll jump in the replies, and also echo what I’m saying or post the receipts.”

Fans and stans have always gone hand in hand with pop culture figures and franchises: Beatles fans followed the members wherever they showed up in the ’60s during the height of Beatlemania; Elvis Presley’s manager, Colonel Parker, encouraged fans to form fan clubs to spread news about upcoming album releases and concerts because they saw the networks’ existence as “another grassroots opportunity for local promotion.” The internet accelerated everything, creating a symbiotic relationship between pop culture figures and the communities that stan for them.

Over time, those public displays of support by passionate fans have become almost synonymous with social media platforms like Twitter and aspects of stan culture. The language used by stans to discuss pop stars (which is primarily lifted from black women and queer communities of color) has spilled over into other communities that aren’t just talking about which pop star just “outsold” the other but are stanning for a congressional or presidential candidate.

Stans for various presidential candidates agreed that the shift in how some of the most dedicated supporters of campaigns were interacting with each other online began in 2015 with the rise of the Bernie Bro — Sen. Bernie Sanders' Extremely Online supporters, stereotyped as young white men who were overzealous in the support for and defense of Sanders’ campaign.

“The Berniebro is #FeelingtheBern. The Berniebro is posting a video on his Facebook wall: You really have to watch this,” wrote Robinson Meyer in 2015, describing the stereotypical Sanders supporter. “The Berniebro solemnly posts links to his Facebook wall that night: Here is the focus group which said Bernie won the debate. Here is an online poll that said the same thing. Here is an online CNN poll that also declared his victory.” A February 2016 Vox explainer on Bernie Bros opens with a comment that journalists and pundits have learned to choose their words carefully. “At this point, it’s pretty much a given that almost anything critical of Bernie Sanders or his supporters will lead to backlash, and perhaps even personal attacks.”

But the political press got it wrong in 2015. The phenomenon wasn’t unique to Sanders — Bernie Bros were just early adopters of stan culture, the influential prototype of our new political reality.

Take Kamala Harris’s now-ended campaign and its online army.

On Twitter, members of the #KHive — which took its name from the #BeyHive, home to Beyoncé stans — presented their candidate as decisive and in possession of a cinematic élan. They fundraised. They praised. They attacked.

When news broke that an aide to Tom Steyer had resigned after stealing voter data from Harris, the #KHive was already prepping content, tweeting at Steyer, drafting their own fundraising tweets, and responding to anyone who had shared the news.

“Oh hell naw!!! I will be addressing this as soon as I get home via video because this is some straight up BS!” tweeted Reecie Colbert from her account BlackWomenViews, which became one of the largest and most vocal accounts supporting Harris’s campaign. “Tom Steyer needs to drop out!”

In a thread of watermarked, well-lit videos posted less than an hour later and addressed to Steyer himself, Colbert sits with the halo of her ring-light setup reflected in her eyes.

“You’re unethical, your campaign is unethical, and you have no place in this primary,” Colbert says in a video posted for her 17,000 followers, explaining that Steyer has had every advantage and privilege. “I have been saying that this operation 'block the black woman' — but GODDAMN, it’s operation ‘cheat the black woman’ too?”

“Does Kamala Harris look like your fucking mule? That’s a serious goddamn question, and you motherfuckers try it because you feel like, ‘I can get away with it. It’s just a black woman. Who’s gonna care?’ OH, WE FUCKING CARE, TOM STEYER,” Colbert says — then plugs a fundraising link for the campaign urging anyone who’d ever felt slighted or cheated to donate to Harris’s campaign.

These kinds of outside efforts, effective as they were (Colbert once raised thousands of dollars for the campaign online through a fundraising link for grassroots supporters), weren’t the extent of #KHive’s activities.

In October, the Harris campaign even hired an influencer and surrogate strategist to assist the campaign on planning media.

#KHive members strategized in group chats, created hashtags to promote campaign videos, and passed along ideas to the campaign. Evans told me that Colbert came up with and pitched the campaign on a video series where Harris, a noted home chef, cooked with voters across the country. (She cooked in the homes of Iowans and Mindy Kaling alike.) In October, the Harris campaign even hired an influencer and surrogate strategist to assist the campaign on planning media. Some of the larger accounts of Harris supporters' told me that the coordinator had reached out to them to let them know that the campaign wanted supporters to use a particular hashtag or themed day; Evans told me he sometimes received deep-cut clips of Harris speeches or hashtag suggestions from campaign aides.

He recalled attending a Harris fundraiser he’d purchased a ticket for in the New York area. “All of her team knew who I was and they were excited that I was there, which was a shock to me,” Evans said. “So they brought me back and I got to meet her and they were like, ‘We talk about you in the office all of the time and her husband loves you.’” The campaign later invited him to CNN’s LGBTQ town hall, where he met Harris’s husband, Doug Emhoff (he calls himself a Harris stan in his Twitter bio), who later tweeted that it was great to meet the “King of the #KHive.”

“We’ve had to pick up the mantle to combat the disinformation because there’s only so much her campaign can do,” Evans added.

Members of the #KHive saw themselves as the unofficial anger translator, rapid-response team, and communication hub for the Harris campaign, which they believed was reserved in its approach to the primary, because Harris would be perceived as too harsh, too loud, and too mean if she were to push back on criticism because she is a black woman. (At one point, MSNBC’s Craig Melvin apologized to Harris onstage at a gun control forum after the network left her out of a video. “I had no idea that it had happened,” he said. “But I heard quickly after from a number of people that it had happened. So I wanted to apologize.”)

“People have figured this out that yeah, if you are saying something that’s negative about Kamala you probably are going to get some people pushing back on you,” Colbert said in an interview.

Colbert and other supporters, like Truman, the data scientist from New Jersey, said that the hashtag and group were born out of their desire for more positive media exposure for Harris, but that the group had also focused the need to counter the avalanche of misinformation, misogynoir, and racism that they say Harris’s campaign faced on social media platforms from other campaigns supporters, far-right figures, and from nativist black movements like the American Descendants of Slavery, which specifically advocates for benefits for black Americans descended from enslaved people brought to America. ADOS activists have specifically attacked Harris, who is the daughter of Indian and Jamaican immigrants, by accusing her of “not being black enough” to understand the needs of black Americans.

“We’ve had to pick up the mantle to combat the disinformation because there’s only so much her campaign can do.”

“These ADOS bots and there are these weird things we’ve never experienced before because when Jesse Jackson ran he was a black man, when Barack Obama ran he was a black man,” Truman said. “Now that a black woman is running it’s a challenge. We’re getting sexist tropes, racist tropes, and xenophobic tropes against her. It’s overwhelming.”

Evans told me that he initially started promoting Harris after watching her question Jeff Sessions and Brett Kavanaugh during their confirmation hearings for attorney general and the Supreme Court, respectively. “It was like when you discover a band that you want all of your friends to know about but nobody knows,” Evans said, adding that many of his followers who’d previously supported Hillary Clinton came along with him.

That link between pop culture and politics was apparent to most people I talked to. “I’m a black gay man — so stan culture is a part of my culture,” Truman told me. “I stan Rihanna and I know there are people that stan some of these generic pop stars and sometimes those conversations can get a little wild.” He thinks that some aspects of the culture that’s forming on Politics Twitter have become more toxic than attacks from stans on people who criticize the musicians they love. “It’s not like, if I’m conversing with a Beyoncé fan and I’m a Rihanna fan and I’m like, ‘Oh, she has all of these number ones that Beyoncé doesn’t have.’ It’s not at that level where you’re getting doxing people, or contacting their employers — it’s nothing like that, but it seems like it’s headed that way in politics.”

It’s those types of interactions between stans of opposing campaigns that have turned bitter and resulted in personal attacks on individual supporters.

In early November, for instance, an email hit the BuzzFeed News tip line, where people often send confidential information about wrongdoing and abuse.

“Even though Beto has dropped out — his fans/stans/supporters are overwhelmingly bitter,” began the email. “So bitter, that they started a ‘Pete for governor’ hashtag on Twitter and it trended for awhile. This is the state of the hate in the party. But WE Pete supporters [are] unified and conquered without hate.”

#PeteForGovernor, a hashtag ostensibly to push Mayor Pete Buttigieg toward running for office in his home state of Indiana, trended for a period of hours on Twitter. Then a “Pete for Governor” website appeared. And then mock Pete for Governor merch appeared. Pete supporters and stans, like the one who emailed us, accused Beto stans or maybe even foreigners of manufacturing the situation. The Buttigieg campaign took note.

“Hello from Pete Buttigieg’s campaign,” read an email from a Buttigieg campaign aide who’d noticed a tweet from a Harris stan that said I was looking to speak with people about the hashtag.

“We had seen some people tweeting about how it was perpetuated by bots and accounts based in the country of Georgia, which raised some alarms on our end because we want to be as vigilant as possible about foreign election interference,” the aide said in an interview.

The Buttigieg campaign asked Twitter to investigate the origin of the hashtag, the aide said. “It was fans of Beto’s now former presidential campaign that had been tweeting it.”

I actually had already contacted the Beto supporters behind the Pete for Governor website before the email tip arrived, and before I talked to Buttigieg’s campaign. Alex, who created the Pete for Governor website and didn’t want to share his last name to protect future job prospects, said the whole thing had been satirical — some tongue-in-cheek retribution for O’Rourke, whose campaign had been plagued by requests and questions about why he wouldn’t just drop out and run for Senate. Alex clarified that he doesn’t actually dislike Buttigieg.

“The website doesn’t put anything about Pete in a negative light,” Alex told me. “It’s just like, ‘Hey, Pete should run for governor. He should come home. It’s a divisive time, and he should come home.’ I think that’s why it resonated with so many people.”

He also said something that many supporters and stans I spoke with volunteered: “The entire primary so far has been very frustrating, because I think Twitter gets a little too much influence in mainstream political discussions.”

It’s a new reality for campaign staffers and stans themselves across the primary who say that the fanbases that have organized various campaigns have created a double-edged sword — one that provides a campaign a fast and free way to spread information and counter misinformation, but has also created an environment where misinformation spreads easily and where their supporters might not be advocating for a candidate in the best light.

“Most of [Sanders’] supporters were younger people, millennials, who were already tuned into social media,” Evans said. “I think this has been the first election where I’ve seen it branch out into other candidates. Everyone who’s running has some kind of online stan culture around them.”

Campaigns have worked on reining in supporters’ behavior on social media platforms. In early February, Sanders told surrogates in an email that he wanted them to be respectful of other candidates in the race and condemned “bullying and harassment.” Buttigieg’s campaign has constantly reminded its supporters of the “Rules of the Road” (a list of very earnest qualities) they want them to adhere to. Almost every Reddit board for candidates includes an extensive admonition to not engage in derogatory behavior on behalf of their candidate.

“On the one hand, when you see someone who supports your candidate just happen to respond to an attack or respond to misinformation organically, or see they’ve tweeted out this interview clip from three months ago proving that there’s consistency, or responding to someone who says ‘Oh, this person doesn’t have any plans’ by linking them to your campaign’s plans before you’ve even seen it — [it] is incredibly useful,” said one Democratic campaign staffer.

One Democratic campaign said it’s noticed that a majority of the attacks on its campaign come from candidates' supporters instead of the campaigns themselves. “We’ll see inaccurate quotes posted by people who say they support different candidates in Twitter bios, and it doesn’t seem like it’s something that’s popping up from journalists a lot of times — it seems like a supporter of a candidate will launch an attack and they’ll get a lot of pickup, and it’s the way that a lot of attacks are getting generated these days, and that seems new for Twitter.”

In fact, it’s a situation that makes some supporters worried that the culture they’re willingly participating in might turn people away from voting at all.

“I’ve seen some really mean things from supporters from every candidate that’s running,” Evans said. “Things that I’m sure they wouldn’t want that candidate to see.” ●