Recently, an acquaintance posted an ultrasound image to Facebook, the customary way to announce a pregnancy in the 2010s. The image was equal parts eerie and expressive: yellow-tinged and three-dimensional, like an infant in the uncanny valley. By the time I saw it, the comments were already rolling in: "Adorable!" "He looks just like his dad!" I clicked "like."

Before the ultrasound, as the 2013 book Imaging and Imagining the Fetus puts it, "the unborn human was hidden." Invented in the 1950s as a medical tool, by the 1980s the 20-week fetal ultrasound was becoming a standard milestone of American pregnancy. And it was doing far more than letting doctors keep tabs on a pregnancy: It was also visually introducing parents to their children long before birth, for the first time in history.

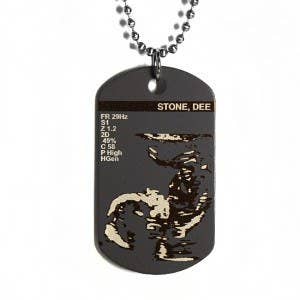

These days, the resulting image has become something more like a sentimental souvenir than a medical one. Some expectant parents visit spa-like "keepsake ultrasound studios" several times over the course of their pregnancy, to capture images at various stages. Others put ultrasound images on cakes and cupcakes, shower invitations, dog tags, and original prints, or subject them to bizarre feats of Photoshop. On the extreme end of the spectrum, you can commission a lifelike doll ($250-$550) based on your fetus's ultrasound. How did ultrasound images become so ubiquitous?

The first trend propelling the rise of the fetal "portrait" is the 3D ultrasound, which offers strikingly clear images like the one I "liked" on Facebook. This newer technology can display distinct facial features and wiggling fingers and toes in much more detail than the grainy 2D black-and-white blobs of yore. "It's the narcissism factor," said Blair Koenig, who has been chronicling parental over-sharing on her blog STFU, Parents since 2009 (and whose own online avatar is an "ultrasound" showing a can of Pabst Blue Ribbon). "If you can see more of your child and you're proud already that your kid has your nose or whatever, of course it's better to show an image that's not totally grainy."

Although 3D ultrasounds are widely available these days, many doctors won't employ them unless they suspect something is amiss with the fetus — and plenty of parents still want to see those clearer images no matter what. Hence the rise of the ultrasound "studio," which dispatches with medical checklists altogether and caters only to parents' aesthetic desires. "We're not doing measurements and we're not checking for abnormalities," said Michelle Radice, who owns a studio in New Jersey. "It's just a bonding experience." Instead of a cold room presided over by a dutiful technician, clients settle into a comfy recliner in a spa setting, with room for the whole family and a sonographer whose only job is to capture that perfect fetal smile. Companies with names like BabyFace and A Peek in the Pod offer "fetal portraiture" sessions; clients can also take home live-action recordings their "4D" ultrasound sessions set to lullabies. (In a few places, safety concerns over the high-powered sound waves — which have never been proven harmful — have prompted a crackdown on non-medical ultrasounds; last year, Oregon became the second state after Connecticut to ban the "keepsake" versions.)

Joli Reid is a co-owner of Baby on Board, an ultrasound studio that opened last year outside Detroit. She had worked as a sonographer at a local hospital for years, and women frequently asked her to reveal the gender early, or to help them see the baby's face. Now she can give then what they want: If the fetus's face isn't visible during a session at Baby on Board, she gives the mother candy and asks her to move around a little, which encourages the baby to shift into a more "camera"-friendly position. "There are a lot of tears and a lot of screams, and it sounds like a party," she said. Private rooms can fit up to 15 people, and many people bring their extended families. Some women come in at 15 weeks for a gender reveal, and then again shortly before birth to capture a more baby-like image. She said women who have had miscarriages sometimes come in as early as eight weeks just to hear the baby's heartbeat. (For $60, they can take home a teddy bear implanted with the recording.)

Many parents also want to know the baby's sex as soon as possible in the pregnancy. "This is a society where you're supposed to start getting kids ready for college when they're 3, so in a way it's consistent," said Sallie Han, an anthropologist at SUNY Oneonta who has studied how women view their ultrasounds. At many of the appointments Han observed for her research, the parents and grandparents were much more focused on the "gender reveal" than the doctors were: More than once, she heard them exclaim, "Now I can go shopping!"

My friend Matt, a father of five in Illinois, visited an ultrasound studio with his wife during her last pregnancy. They generally rely on "crunchy" birth care providers who don't recommend the scans unless they suspect a problem, but Matt's wife was eager to find out the baby's gender. They toted their four other children down to a studio in a strip mall, and for $40 they found out and got to take home a print-out. (It was a boy, the family's fourth.) The experience was a little surreal, he said — flat-screen TVs and tchotchkes everywhere — but it was also memorable and fun.

"It was a really sweet moment for the other kids, who were dizzy with anticipation," he wrote in an email. And "especially as a father, who doesn't get the deep and intimate connection the mother has with the child during pregnancy, that can be a moment where the whole thing becomes a lot more real." He used the ultrasound image as his Facebook cover photo for awhile.

And that's the other obvious explanation for the 21st-century popularity of the ultrasound image: social media, which enables parents to share every single milestone with a larger circle than ever before. It was the proliferation of ultrasound imagery on Facebook that prompted Priya Kumar to write her 2014 master's thesis on new mothers' decisions to share baby photos online. "Their digital footprint exists before they do, before they're even born," Kumar recalled thinking. About half of the women she interviewed shared ultrasound images on a social network, sometimes using them as a birth announcement; one posted her own ultrasound photo side-by-side with her son's. For the mothers Kumar interviewed, the images signified "the baby's real, it's in there, and this is what it looks like."

The unavoidable subtext of posting very early ultrasound images to Facebook is that this publicly frames even very young, non-viable fetuses as "babies." This isn't a new observation: In an influential 1987 article in Feminist Studies, scholar Rosalind Petchesky critiqued ultrasounds as fetishistic images that "blur the boundary between fetus and baby." New technology — and the ability to disseminate it — has blurred the line between medical image and "baby's first photo" even more dramatically than Petchesky could have anticipated, and there seems to be no going back. The images are also often criticized, of course, as a weapon wielded by opponents of legal abortion. According to the Guttmacher Institute, 23 states now regulate the provision of ultrasounds by abortion providers, often motivated by the idea that a woman who sees the image will be less likely to terminate her pregnancy.

For most of the parents-to-be happily sharing images online, however, ultrasounds aren't about politics. When I asked other friends on Facebook for their ultrasound stories, it became clear that no matter what doctors and social critics might say, the ultrasound has become something deeply meaningful. I read stories about images framed at home, stuck in wallets, and emailed to family members; one friend posted hers on her refrigerator as a reminder to pray for her daughter. Another who recently miscarried said the first thing she did when she found out was to shove the images in a drawer.

There will always be skeptics who dismiss the increasingly public ultrasound image as tacky, overly personal, or boring. But they may be consoled by the fact that for many parents, the ultrasound's power is short-lived. "When I was pregnant, my babies always felt so close yet so far away, and the ultrasound pictures were a great consolation until the babies were born," my cousin's wife told me on Facebook. "I stared at those blurry black and gray pictures for hours, even when they only showed indistinguishable shapes, and shared and posted them as if they were portraits." But, she added: "Once the kids were born, they lost their meaning to me."