Back in February, on a trip to Washington, DC, New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker made time to meet privately with Democratic National Committee members from Georgia — a small but influential group of party officials who, until last year, held key superdelegate votes in the presidential nominating process.

Before he got in the race last week, Joe Biden’s campaign manager, Greg Schultz, met with a similar constituency: chiefs of staff to Democratic members of the House of Representatives.

On the campaign trail, California Sen. Kamala Harris makes it a point to check in on superdelegates wherever she goes, tasking a senior adviser to keep tabs on all 769 in a carefully monitored spreadsheet.

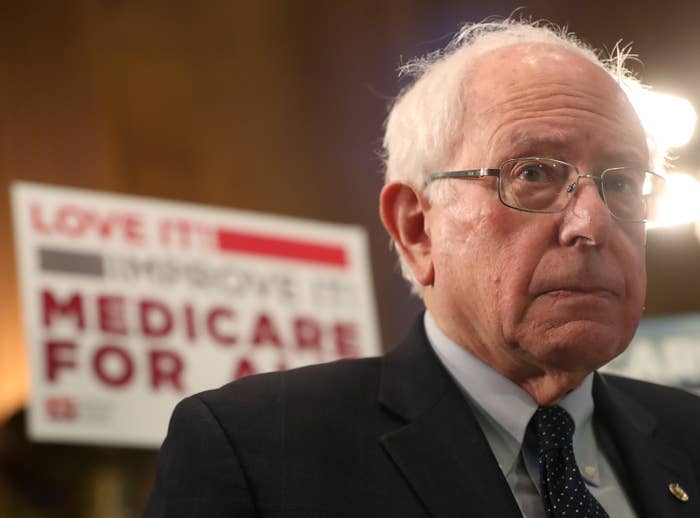

And after helping to strip superdelegates of a significant portion of their power after his first presidential campaign, Sen. Bernie Sanders' campaign officials are planning to take “superdelegates strategy seriously,” they say, with an outreach program designed to “prepare for multiple convention scenarios” — even as the candidate continues to bemoan superdelegates at his rallies.

Superdelegates — the elected officials, party officers, and activists who have been given a say in the Democratic nominating system since 1982 — were stripped of their vote in the first round of convention voting last year, a move to appeal to Sanders supporters who felt the system unfairly benefited Hillary Clinton in 2016. But across the field of 21 candidates, campaigns with the resources to do so are already courting superdelegate support to prepare for the possibility of a contested convention next summer — a scenario in which superdelegate votes could come back into play.

“We're taking superdelegates and superdelegates strategy seriously,” a Sanders aide said, “hence having a team dedicated to delegates who can prepare for multiple convention scenarios. We will be reaching out to them over the course of the campaign. When the senator wins the nomination, he's eager to work with them to support and unite all the party in the general and beyond.”

On the campaign trail, the 77-year-old Vermont senator periodically brings up superdelegates. In his speeches, they are one in a long line of proof points that his “political revolution” prevailed because of grassroots strength and despite an establishment fighting to undermine his support.

In the last Democratic primary, superdelegates made up about a third of the 2,382 delegates needed to clinch the nomination. They include elected officials such as members of Congress, “distinguished” party leaders like former presidents and vice presidents, and the 450 or so members of the DNC, ranging from state chairs to longtime activists.

The superdelegate system emerged as a real and symbolic point of contention during the 2016 primary — allowing Clinton, a two-time presidential candidate uniquely positioned to lean on long-standing relationships across the party, to declare a seemingly insurmountable advantage before voting even began. In summer 2015, five months before the Iowa caucuses, her campaign let it be known that Clinton already had commitments from about 440 superdelegates, putting her at close to 20% of the total delegates needed to win the nomination at the convention.

To many, it’s a confusing, arcane system that puts too much power in the hands of insiders. To others, including black leadership inside the Democratic Party, it’s been one way to empower voices that historically have been shut out of the process. Last summer, as Democratic officials prepared to vote on the proposal to strip superdelegates of their power, DNC Vice Chair Karen Carter Peterson, along with other DNC members of color, appealed to her colleagues to reject the changes: “Are you telling me,” she asked on the floor, “that I’m going to go to a convention, after my 30 years of blood, sweat, and tears for this party, that you’re going to take away my right?”

In the end, the changes were adopted — but if voters don’t coalesce behind a single candidate by the time Democrats gather in Milwaukee for the convention next summer, requiring a second or third round of voting, they could see superdelegates reemerge as a deciding block.

Democrats believe, and hope, that the scenario is more unlikely than not — even with Sanders promising to eke out a small-margin lead in a historically large Democratic field. (“Last time you had to get 50 plus 1 to win,” his pollster, Ben Tulchin, said last month. “Now we need basically about a third to win. And others have a lot farther to go than us to get to that third.”)

Mark Longabaugh, a former Sanders adviser who helped oversee ballot access and convention strategy in 2016, said he “can’t conceive” of a primary where more than two contenders end up scoring delegates in equal measure. To do so, he said, you’d have to see delegates scattered across the field, with perhaps every candidate taking his or her home state: If Sen. Amy Klobuchar won in Minnesota, John Hickenlooper in Colorado, Harris in California, Sen. Elizabeth Warren in Massachusetts, and Beto O’Rourke or Julián Castro in Texas, said Longabaugh, “that’s the scenario that would create a convention where maybe somebody can’t get there all the way.”

“And I find this implausible, too, just given the way momentum works coming out of the early states.”

The closest analog might be the 1984 Democratic primary, when Gary Hart and Jesse Jackson held enough delegates that Vice President Walter Mondale had to rely on superdelegates to put him over the top.

As of this spring, according to an operative tracking the list, there were 765 superdelegate votes. (Each of the eight DNC members who live overseas and make up the “Democrats Abroad” delegation gets half a vote.)

Of the Democratic campaigns thinking about superdelegate outreach, Harris’s has the most organized and tactical operation. One of her senior advisers, David Huynh, oversaw Clinton’s exhaustive delegate-tracking program in 2016 before leading the effort to wrangle votes in Tom Perez’s successful campaign for DNC chair.

“The one that I've heard from, from their delegate tracker, is Kamala,” said Leah Daughtry, a superdelegate and veteran Democratic Party official, referring to Huynh and his team.

“He gets it, and so he’s on it,” Daughtry said.

An official from Harris’s campaign pointed out that superdelegate outreach is good politics regardless of whether they factor in the convention. “All of these people — whether they are DNC members or members of Congress — have footholds in their communities,” the Harris official said. “Obviously we are reaching out to those individuals and doing our due diligence.”

Sanders has also tasked Matt Berg, a former 2016 aide, with overseeing delegate strategy and ballot access, including superdelegate outreach. (After Sanders ended his first presidential bid, Berg worked closely alongside Huynh on Perez’s DNC campaign, helping to lead his whip operation.)

Sanders aides say they hope to be in contact with superdelegates earlier in the process than last time, when a last-ditch effort to court their support prompted one supporter to encourage Sanders voters to “harass” superdelegates by posting their contact information in an online “hit list.”

Several operatives noted that South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg might have an advantage with the 450 or so superdelegates who are DNC members. In 2017, Buttigieg ran for DNC chair against Perez, helping to boost his national profile, though he dropped out of the race before voting. (Even though the 37-year-old mayor caught the attention of DNC members during the chair race, he secured only about seven committed votes, according to two operatives tracking the race at the time. Six were from his home state. The other was from Nan Whaley, a fellow mayor from Dayton, Ohio, who has now endorsed his presidential campaign.)

The Booker, Buttigieg, Biden, and Warren campaigns did not respond to requests for comment or declined to comment.

“Look, it’s smart politics in the sense that, if you have the bandwidth and capacity to do it, it’d be very smart to be ready for that contingency,” said Longabaugh, the former Sanders adviser.

“But I would argue for putting more time into trying to win Iowa and New Hampshire.”

Ryan Brooks contributed reporting.