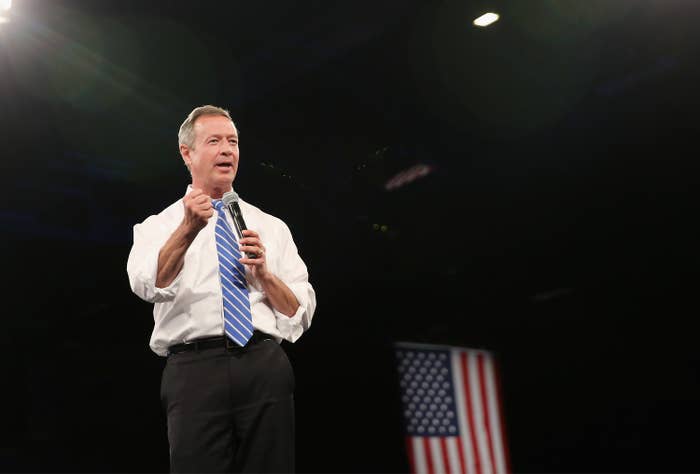

Martin O’Malley is poised to become the first major candidate in eight years to publicly finance his presidential campaign.

The former Maryland governor will likely accept matching payments once the Federal Election Commission deems him eligible in a decision expected as early as this week, an O’Malley aide confirmed. “We’re likely to be deemed eligible and likely to accept,” the aide said.

The move reflects a campaign up against its own limitations, short on time and money, yet pressing forward. After five months in the race, 18 trips to Iowa and 10 to New Hampshire — after trying again and again to will the polls upward, to find his footing and finally take off — O’Malley is still trying, though now with equal parts resolve and resignation. His team is pursuing a public funding option that would keep them afloat in the short term, while locking the campaign into a set of restrictions that would almost certainly guarantee failure in the long term.

The taxpayer-funded system for presidential primaries, designed to match contributions up to $250 per person, would help sustain the O’Malley operation into the early caucuses and primaries. But should he agree as planned to receive matching funds, O’Malley will also submit to severe spending limits, curbing resources overall and in each state.

The public finance spending rules would cripple any candidate. But the state limits would pose a particular challenge for O’Malley, whose advisers announced a plan this week to redirect staff and resources to the early states, with an emphasis on Iowa, as reported first by MSNBC. If the election were held this year, under the public finance system, his campaign would not be able to spend more than $1.8 million in Iowa and $960,000 in New Hampshire, according to the FEC’s current estimate of the annually adjusted limits.

The matching program also limits a campaign’s primary spending to $48 million — about half the $100 million fundraising goal Hillary Clinton's campaign set for 2015 alone.

The last major candidate to adhere to such strict spending limits was John Edwards, the former U.S. senator and vice presidential nominee who opted into the matching program in the fall of 2007.

His campaign manager, Joe Trippi, now likens a publicly financed candidate to a terminally ill person on life support. If O’Malley goes through with his plan to accept matching funds, “that is effectively the end of his campaign,” said Trippi. “No campaign that is serious can win taking that money.”

“It is a brutally tough decision to make,” he said. “They know this — it’s akin to a doctor sitting down a patient and telling them they are terminally ill, informing them that they have days to live and there is nothing that can be done to save them, but there is something that can be done to give them another few months of life.”

And given the choice, “who wouldn’t pick extending the inevitable?” said Trippi.

The matching system would likely afford O’Malley the very same opportunity. Aides have maintained that his is a “lean” campaign, designed with sustainable overhead costs and built to carry the candidate through Iowa, New Hampshire, and onto the Super Tuesday states.

But O’Malley has raised and spent money on a vastly smaller scale than his rivals. In the last fundraising quarter, Bernie Sanders brought in $26 million, right behind Clinton’s $30 million. O’Malley, meanwhile, raised $1.3 million and reported having just $800,000 in the bank. Worse, disclosures showed that O’Malley effectively began the next quarter with even less money: At the time of the filing deadline, his campaign had yet to pay some of its September expenses, including hundreds of thousands of dollars in payroll.

An O’Malley spokesperson declined to comment on the thinking behind the decision to pursue public financing.

Eight years ago on the Edwards campaign, as Trippi recalled, they knew they were done either way: “We had to make the decision to either leave the race or take public funding and stay in, knowing that if we took the funds we were dead.”

The week they went public with the decision, Edwards worked to cast the move as “a principled stand,” not a “money calculation”; his aides tried to calm questions and concerns about the spending limits; and Trippi found himself trying to explain negative comments he’d made years earlier about public finance, unearthed and reprinted by reporters.

He offered his best defense at the time: “It’s a different time, a different year,” he told the Washington Post in 2007. But he now admits that was only “the best spin I could come up with.” Eight years later, he said, the matching payments system remains untenable. “I actually thought Edwards would be the last candidate to do it.”

“I have no glee in saying any of this... It’s a horrible way for a campaign to die.”

Update (Nov. 19):

Filings with the FEC show that O'Malley applied for public financing eligibility in a letter dated Nov. 2. He also sought matching funds for 897 contributions of amounts up to $250. The request would direct an additional $339,873.11 into the campaign. The influx would help propel O'Malley forward, but only by so much: At his operation's current size, the matching funds would cover roughly one month's payroll.