She went after a colleague so forcefully that she was silenced by Mitch McConnell on the Senate floor. She thoroughly embarrassed top regulators and dressed down not one but two Wells Fargo CEOs. “You should resign,” she told the first in 2016. “At best you were incompetent, at worst you were complicit — and either way you should be fired,” she told the second in 2017. Even now, they remain the most-watched videos of her on YouTube: otherwise-dry hearings and Senate procedures turned into a display of her fierce and uncompromising brand of intellect.

This Elizabeth Warren, largely absent from her 14-month-old presidential campaign, has come out in full force over the last week.

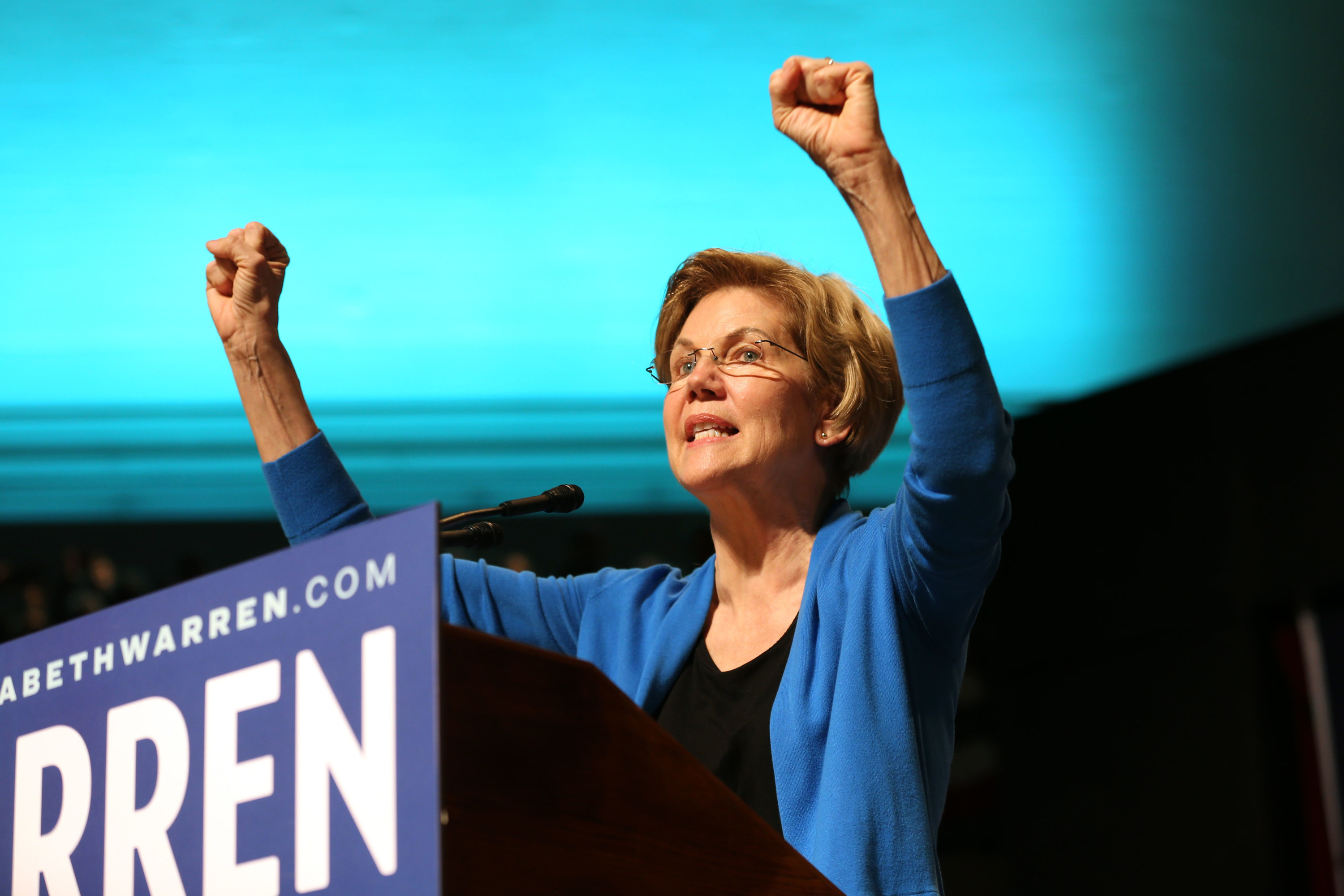

Voters have seen Warren tear into her opponents on the debate stage, politely but a little ruthlessly, with laser-like precision. They watched her dispense with her usual folksy introduction before a crowd of 7,000 in Seattle — “I thought I'd tell you a little bit about myself” — to launch instead into a new condemnation of the “big threat” posed by Michael Bloomberg “Not a tall one, but a big one,” she said. And on Tuesday night, they heard Warren voice something she has long believed — but never before laid out explicitly or publicly: “I think I would make a better president than Bernie.”

The arrival of a more aggressive and uninhibited Warren comes as the 70-year-old Massachusetts senator faces an urgent moment of reckoning: Warren, a politician known for her consistency and discipline in matters of strategy and message, will have to dramatically change the dynamics of the race if she hopes to compete on and beyond Super Tuesday next week, when a third of delegates will be awarded in 14 states.

She has yet to place higher than third in a state and is not expected to do so in South Carolina this weekend. In critical Super Tuesday states such as California and Texas, she is still polling behind Sanders, Bloomberg, and Joe Biden.

Facing perhaps unanswerable questions about what went wrong with her once-ascendant campaign, Warren has returned to the fights that made many Democratic voters fall in love with her in the first place. But she has also compromised some of her long-unwavering positions.

In the last week, voters saw her openly embrace a new super PAC supporting her campaign, the kind of big-money political organization she has railed against repeatedly since entering the race. They saw her allies begin sending out invitations for high-dollar fundraisers. And they have seen her go after Sanders, a longtime ally, after telling reporters dozens of times over the last year, “I’m not here to attack other Democrats.”

At a debate on Tuesday in South Carolina, after a week of more tentative comparisons, Warren launched the direct attack on Sanders that some of her allies had been agitating for. “Bernie and I both wanted to help rein in Wall Street. In 2008, we both got our chance. But I dug in. I fought the big banks. I built the coalitions, and I won,” Warren said in Charleston.

"There is no treading water at this point in the race. You either sink or swim,” said Adam Green, a progressive strategist who cofounded a group, the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, that supports Warren and says it coordinates with her campaign on strategy.

Green, who has been pushing the case that Warren is a better and more reliable implementer of progressive policy than Sanders, said her more combative debates over the last week have given voters the chance to see “the strong fighter who challenges power — the Elizabeth Warren America loves.”

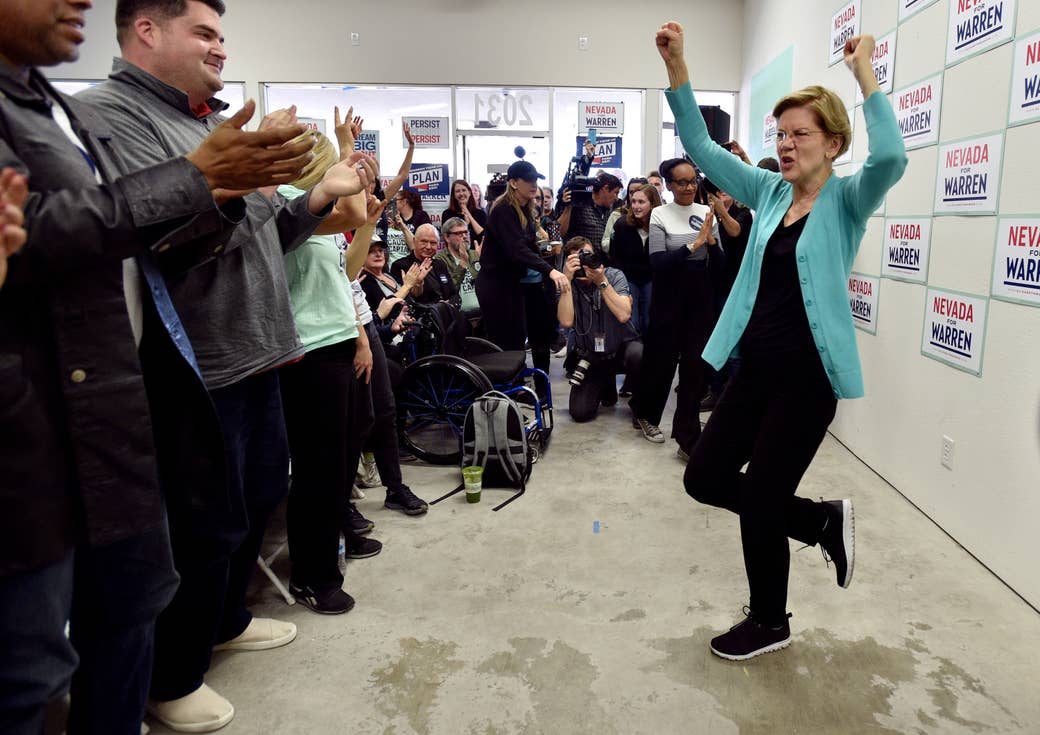

In recent days on the campaign trail, Warren has looked, quite simply, to be having fun — something that had not quite seemed true for weeks, as she slogged through Iowa and New Hampshire with trips back and forth to DC for President Trump’s impeachment trial. The morning after last week’s debate, Warren was almost giddy as she lit into Bloomberg again in front of a group of loyal volunteers packed into a Las Vegas storefront. In Seattle, she could only get through the words “Since Wednesday night—” before the crowd interrupted her with a roar, and when she raised her fists above her head, as she often does, she turned it into a dance.

Inside the campaign, aides are reticent to talk about Warren’s thinking, and bristle at the suggestion that she’s made any fundamental changes: She knows genuinely why she is running, they say, and that can take you far. If anything has changed in the last two weeks, it’s the threat of Bloomberg, the former mayor and billionaire whose self-funded campaign embodies much of what Warren believes is broken in government and politics, that has unleashed her attacks.

People who have spoken to her since the debate last week said Warren has remarked on how many women have come up to her, in public and in private, to say how glad they were to see a woman hold a man accountable like she did.

“Women can be tough,” she said after a woman thanked her at an event in Denver.

After getting in the race at the start of last year, Warren rose to the top of the Democratic field that summer by releasing a steady stream of plans and keeping her focus trained unshakably on a message aimed at moderates and progressives alike. Then she fell back in the polls by doing much the same thing.

Even at her lowest point, as a disappointing third-place finish in Iowa turned into an even worse performance in New Hampshire, there was little consensus among her allies about what had gone wrong, and what — if anything — Warren should be doing differently.

Some cited the influence of sexism as a factor in her struggle to lock down support as voter anxieties about “electability” mounted; others say they wish she spent money on polling, put more surrogates on television, or invested in advertising to cement her lead last summer.

People involved in fundraising for Persist PAC, the new group supporting Warren, say they will aim to do what the campaign was only able to in small measure: amplify her basic message on TV with the financial support of the national donor network Warren developed in her 2012 and 2018 Senate bids but set aside last year when she decided to abstain from high-dollar fundraising.

“She probably should have had it from the beginning,” Sean McElwee, whose think tank Data for Progress has advised the Sanders and Warren campaigns on policy, said of a super PAC.

Warren’s campaign tried to appeal, in part, to the Democratic establishment, at least compared to Sanders’ firebrand policies — offering a “unity candidate” that could win the support of both moderates and progressives. But without a super PAC, McElwee argued, there was no mechanism for big donors to back Warren over Sanders.

“A super PAC allows the establishment to fund the campaign,” McElwee said.

Persist PAC, which is run by four women veteran operatives in Democratic politics, will have its own pollster, a basic function of campaigns that Warren has also sworn off this cycle, to determine what about her pitch is working best with voters, the people said. (Election laws prohibit the super PAC from coordinating with the campaign. A spokesman for the group said there are no former Warren staffers working on the PAC.)

On Monday, Persist PAC announced its latest round of spending, placing more than $3 million worth of pro-Warren ads in more than half of the Super Tuesday states across broadcast, cable, and digital platforms. The ad buy spans 13 media markets in eight states, but in places like California, where paid media campaigns are expensive, $3 million makes up a fraction of what other candidates, in particular Bloomberg, have spent and will spend before March 3.

There is some evidence that voters like what they’ve seen in the last week. Warren raised $9 million in the three days after the Las Vegas debate and saw a bump in some of her polling numbers. And in an immediate post-debate poll, 40% of people who watched Tuesday night said they were impressed by Warren’s performance, putting her near the top of the candidates.

“I don't like to second guess the campaign, but I do think many people needed to see her killer instinct to believe she could win,” said Evan Sutton, a progressive operative and organizer who is supporting Warren.

"I don't know whether or how it could have been done earlier. Until Michael Bloomberg stepped onto the stage, there was no one she could go after with that kind of ferocity without risking major blowback,” he said, citing Sen. Kamala Harris’s attack on Biden and his record on racial justice issues in the first Democratic debate, a move that raised millions of dollars but that later many dismissed as a manufactured product of debate prep.

Warren’s fiercest supporters are sensitive to the idea that the approach represents a change at all.

“I don’t think we have seen some kind of new Warren,” said Murshed Zaheed, a Democratic strategist who is among her most forceful boosters in online progressive communities. “That's the Warren I have known dating back to my time in [former Senate Majority Leader Harry] Reid’s leadership office. That's who she is.”

Zaheed, like many of Warren’s supporters online, uses the turtle emoji as a talisman for the campaign’s approach and sensibility. “Slow and steady 🐢,” he said in an email.

Warren’s window to move ahead in the field, however, is rapidly closing. Sanders’s decisive victory in the Nevada caucuses, where he won 40% of the vote, set up an immediate and existential moment in the nominating process: In less than a week, unless the field of eight remaining Democrats begins to shrink, Sanders could emerge from Super Tuesday with a delegate advantage that makes it increasingly difficult for a single other candidate to retake the lead.

Sanders, who became the target of a new wave of attacks on Tuesday night in South Carolina, is making a play to win Warren’s home state of Massachusetts, with two rallies scheduled there this week.

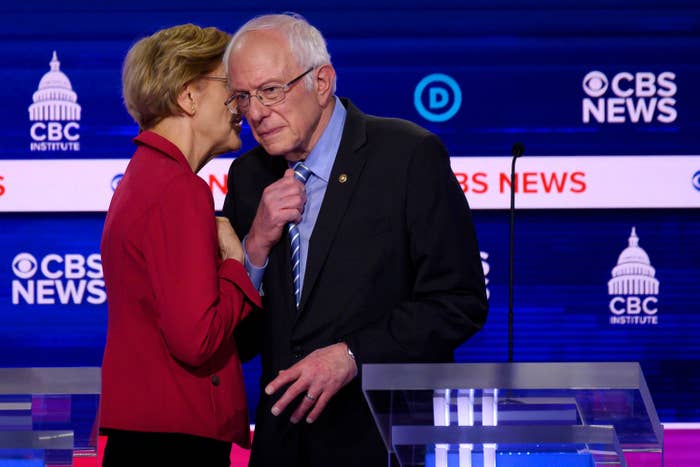

Sanders and Warren, two progressive icons who have worked side by side since before they were colleagues in the Senate, have been careful in the way they interact during the primary.

In January, they clashed for the first time over their conflicting accounts of what was said in a private meeting where Warren asked Sanders whether he believed a woman could win against Donald Trump in 2020. Shortly after Warren issued her own statement about the meeting, sparking a new wave of discussion about the conflict online, one of her campaign officials moved to calm her supporters. “Our goal is de-escalation and focusing on our shared goals,” the staffer wrote to a large group of prominent Warren supporters in a shared private direct message channel on Twitter.

In the DM group, which is still active, supporters have grown increasingly negative on Sanders, one member said, but Warren campaign officials in the group have mostly stayed out of those discussions when they arise.

For those on the left, the difference between Warren and Sanders has less to do with policy or ideology than with questions of progressive power and theories of change. If he is leading a political revolution, then she has honed a more tactical and methodical approach to government regulation and oversight, coupled with the public displays and confrontations in the Senate that would generate dozens of headlines and millions of views on YouTube.

“She began to do what no other candidate can do — make the effectiveness contrast with Sanders from a progressive perspective,” Green said of the debates in Nevada and South Carolina.

But on Tuesday in South Carolina, Warren’s sharpest attacks were still aimed at Bloomberg.

A few minutes into the debate, Bloomberg declared, “I have the experience. I have the resources. And I have the record. And all those sideshows that the senator wants to bring up have nothing to do with that.”

Warren jumped in, talking over Biden until she won the chance to speak.

She turned to a familiar story, one that she has been repeating almost daily on the campaign trail for 14 months: “When I was 21 years old, I got my first job as a special education teacher. I loved that job. And by the end of the first year, I was visibly pregnant. The principal wished me luck and gave my job to someone else.”

This time, though, her voice rising with emotion, Warren added a different ending, one borrowed from a lawsuit against Bloomberg by a woman employee.

“At least I didn't have a boss who said to me, ‘Kill it,’ the way that Mayor Bloomberg is alleged to have said to one of his pregnant employees.”

UPDATE

This story has been updated to clarify Data for Progress's work.