The emails started last Sunday, April 14, 6:37 p.m., with a grim warning.

Subject: "We are under attack."

“... An organization that is the epitome of the political establishment — the Center for American Progress (CAP) — unleashed and promoted an online attack video against Bernie.”

There was another on Tuesday morning (Subject: “A serious threat to our campaign”) with the news that Democrats who supported Hillary Clinton in 2016 — dubbed "‘Stop Sanders’ Democrats" in a page-one New York Times headline — were “increasingly worried,” “agonizing over his momentum,” and “jittery (again).” Later that night, another email: They were launching an “emergency 48-hour fundraising drive.” (Subject: “An ‘anti-Sanders campaign’ is starting ‘sooner rather than later…’ We have to be ready.”)

Forty-eight hours passed, and the emails kept coming. By the end of the week, there were six fundraising appeals and 14 mentions of a Democratic establishment already “planning” and “plotting” to “derail our movement" and “defeat our political revolution.”

“... Do you know how powerful you are, [NAME]?”

“... They are terrified of our movement — as they should be."

“... Add a contribution before midnight to send an unmistakable message.”

“… We cannot underestimate what they will do to try to take us down.”

“... The political and financial establishment are plotting against us.”

“... Bernie can't do it alone.”

The fundraising drive could have easily been mistaken as a series of emails from the height of the last Democratic primary — a two-person race between Bernie Sanders and a candidate with all the money and endorsements and few Democrats willing to challenge her ascent to the nomination that played out cleanly as a referendum on institutional forces that had “rigged” not just the economy but the political process too.

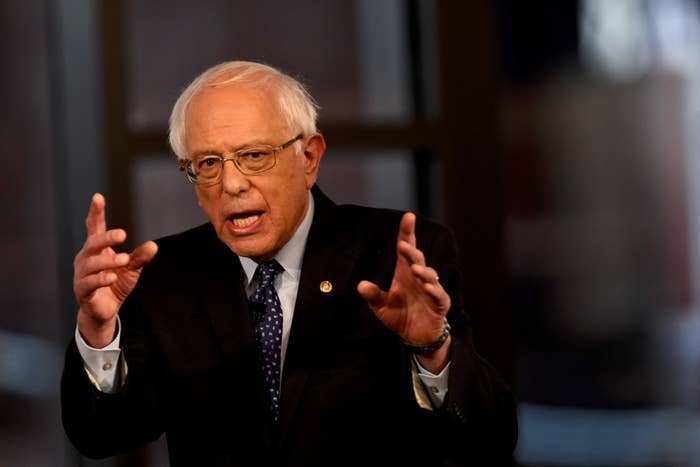

Four years later, in a field of nearly 20 candidates, if Bernie Sanders is still running against the establishment, this time it’s on more complex political terrain: The 77-year-old senator, leading the field of declared candidates in early polling, is both fighting to lead and unite the Democratic Party he’s helped transform, while also recreating the antiestablishment sentiment that fueled and funded his 2016 bid.

On the trail, at almost every rally, Sanders does not hesitate to revisit the topic. In interviews, he will tell you he works closely with party leaders (“We speak to the DNC every week,” he said during a Fox News town hall last week, “and I think the process will be fair”) just before he vows to take on the “Democratic establishment,” along with the drug companies, the insurance companies, and the military-industrial complex.

And last week, during a bus tour across the Midwest aimed at winning back blue-collar support from Donald Trump, his campaign was quick to air its grievances against the Center for American Progress, a prominent liberal think tank founded by Clinton’s former campaign chair, John Podesta. (The group’s political arm owns a left-leaning news outlet, ThinkProgress, which published a story and attack ad–style video about Sanders’ newly accumulated wealth, prompting Sanders to accuse the think tank of sponsoring a “smear” campaign against progressives.) On Twitter, Tim Tagaris, the strategist leading Sanders’ digital fundraising program, asked loyal supporters to pitch in. “You know what to do,” he said. (No explanation needed.) And on cable news, former Clinton and Sanders operatives returned to make the rounds. (An establishment effort to stop Sanders would be a "mistake," said a former Sanders adviser, Mark Longabaugh, in an MSNBC segment last week. On set, a onetime rival, Clinton 2016 spokesperson Brian Fallon, nodded in agreement. Donors "might as well light their money on fire.”)

Sanders, as his campaign advisers see it, isn’t fighting the last war. The other side is.

“Listen, when we’re attacked, we are gonna fight back,” said Ari Rabin-Havt, who serves as the Sanders campaign’s chief of staff. “But if people who are fighting the last war are going to swing punches against us, it is unfair to think we're going to sit quietly by.”

“We are going to win this primary, but if we don’t, he will do whatever it takes to defeat Donald Trump. If the nominee is Bernie Sanders, will those Democratic insiders fully support a Bernie Sanders campaign? Will they put aside their personal animus?”

Other Democrats, including some Sanders allies and former aides, see a candidate unwilling to adapt to the new landscape of the 2020 primary. “He's running to lead the party. This is a different race. This is a different framework,” said one operative close to the Sanders operation. “That's not the energy that you want to tap to try to win this thing.” Another put it this way: “It’s like he’s trying to make the freshman album again,” the strategist said. “He’s stuck at 20% [in primary polling], and he’s playing to that 20%. Maybe it’ll raise you money, but it won’t put you beyond that 20%.”

"Sanders' brand is fighting the establishment. It's who he is. It's core to his appeal. But the landscape is different this time," said John Neffinger, a longtime progressive operative. "Voters have more choices, which argues for leaning into that strength, but they also want someone who can unite the party in the end."

Ahead of his February campaign launch, a number of senior advisers, including Longabaugh, whose consulting firm has since split with the campaign, warned that Sanders, a longtime independent who made a point of filing his 2024 Senate reelection paperwork as a third-party candidate on the same day he registered as a candidate in the 2020 Democratic primary, would need to work to unite the party behind him.

Sanders advisers now describe a scenario where the senator captures the nomination with less than a plurality of support from Democrats — setting up the possibility of a multiple rounds at the national convention next summer.

“Last time you had to get 50 plus 1 to win, and we started at zero,” said Ben Tulchin, the campaign’s pollster, who recently conducted surveys showing Sanders leading Trump across three key Midwest states: Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania. “Now we need basically about a third to win. And others have a lot farther to go than us to get to that third.”

Asked if the attacks against the “Democratic establishment” would limit Sanders’ ability to expand his support in a primary electorate, Tulchin pointed to the senator’s support among independents — a voter block that aides see as key to pushing past that 20% base. “Picking on Washington insiders is always going to be popular with voters,” Tulchin said. “It just strengthens him with independents and with people who are frustrated with the political and economic status quo.”

If a single moment defined the senator’s first presidential bid — one that marked the point at which “the tables began to turn,” as Sanders’ former campaign manager, Jeff Weaver, puts it in his book, How Bernie Won — it was the morning of Oct. 18, 2015.

Multiple Sanders aides had just been caught taking advantage of a glitch in the DNC’s voter software, allowing them to access proprietary Clinton data. In response, the Democratic Party chair temporarily blocked Sanders from using the voter file. That morning, reporters gathered outside the row house that served as the campaign’s Washington office for a press conference with Weaver. They expected a formal apology.

Instead, they heard Sanders’ campaign manager accuse the Democratic Party of “actively attempting to undermine our campaign.” This, Weaver told reporters, was “sabotage” by the establishment. A “heavy-handed” attempt to “undermine” a grassroots campaign. Part of a “pattern of conduct” by party leaders to “help the Clinton campaign” and “attack the heart and soul.”

“We need our data, which has been stolen by the DNC,” Weaver said, to “vindicate the rights not only of this campaign, but of the millions of people across the country who want change.”

Inside the campaign, where more junior staffers had urged the candidate to offer a more conciliatory response, the candidate and his staff saw the impact immediately. In Iowa, volunteers were “cheering” as they watched the press conference; online, more than $2 million came rushing in; at rallies, crowd attendance “swelled.” People were energized by the campaign’s willingness to call out a “party establishment” that put its “fingers on the scale.” And for Sanders, Weaver writes, it was a “valuable lesson”: “to win, one had to be on the offensive.”

The second time around, their approach hasn’t changed.

“Bernie got attacked and he responded and defended himself,” said Tulchin, the Sanders pollster. “In the context of a general election with Trump — who attacks people at will, calls them names — voters are going to want to know someone can stand up for themselves and defend themselves. That’s core to who Bernie is.

“If he were not to do it, they would wonder about it.”