GEVGELIJA, Macedonia — For months in this small Macedonian border town near Greece, refugees desperate to head north would pack the train station at Gevgelija, sometimes clambering aboard through windows with little interference from authorities.

But on Wednesday, as a wave of refugees flowing in from Syria, North Africa, and Afghanistan continued to unfurl across the eurozone, all was quiet at the station.

"New rules," said one employee.

Trains that once carried the refugees instead stop closer to the border, keeping them out of local cafes, streets, and other sites that had been trying the brittle patience of Gevgelija residents.

Hundreds of thousands of refugees have been flowing through border towns like Gevgelija on their way to western Europe in search of safety. But they have had to pass through regions where patience wears thin and sympathy can often run short.

The unnamed camp — which now documents the majority of the refugees crossing the border into Macedonia — is a short drive from the station, and sits on a route common for refugees heading to western Europe.

Most people BuzzFeed News spoke to at the border said they had travelled from Afghanistan and Syria by way of Turkey and Greece.

Refugees arriving from Greece were held by guards at the railway line before being brought across to the camp in groups. There, a bleak stay awaited them.

White tents and wooden blocks were cornered off with a large gate and fencing. Inside, they registered and had access to bottles of water while purchasing tickets for travel to the Macedonia-Serbia border in the north. For the large number of mothers and children arriving into the camp, there was a tent which offered toys and supplies for babies.

Dalal, who was waiting to board a train with her four children – Sang, Elma, Mahmoud, and Reem – planned to meet her husband in Germany, having left everything behind in Aleppo, Syria.

"She can be heavy," Dalal said, gesturing towards the baby she held in her arms before passing her over to 16-year-old daughter, Elma.

In Syria, Dalal was a primary school teacher. "It was very hard, we had to leave," she said. "We left all of our bags, all of our things, everything. Now, we have nothing. I just want to go and see my husband."

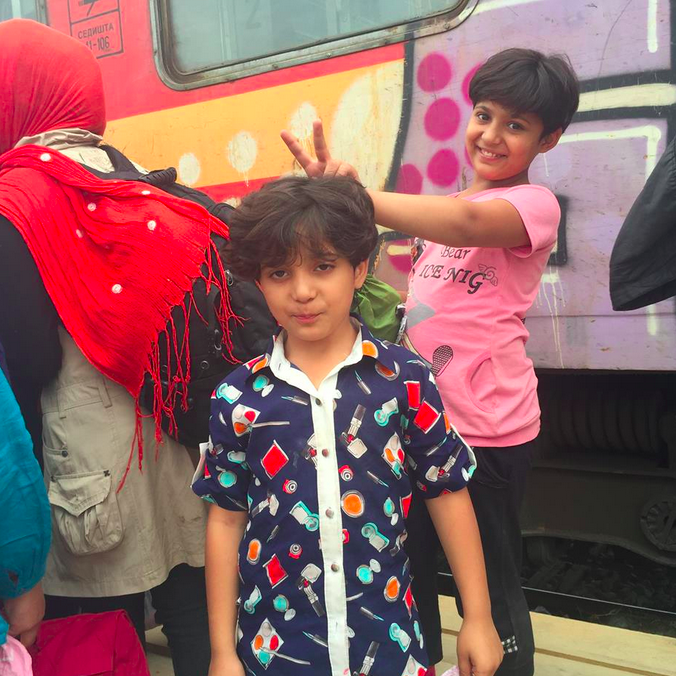

Nasal from Afghanistan was already with her husband, Mohammed, as they waited to board a train on their way to Germany. With them were their three sons, including 8-year-old twins Masamour and Fareed who wore matching patterned shirts.

"These are my babies," Nasal said proudly.

When asked for permission to take the family's photo, Mohammed jumped up to straighten the twins' shirts and spent several minutes slicking back their hair.

"Our journey has been long and hard," he said, holding his sons' hands as they walked up to board the train.

Stories of lives and plans obliterated by war and violence were familiar at the camp.

Maream, who fled Syria with her husband and two-and-a-half-year-old son, had recently qualified to be a pharmacist. A month ago, she was forced to flee.

"I studied to be a pharmacist while I was pregnant at home," Maream said while waiting to board a train. "Then my life was snatched away without any warning. Now, I worry that I'll have to do my training all over again. Five years, it took me five years to complete it."

If she had stayed in Syria, Maream said, she wouldn't have been allowed to leave her home, much less work, and her son would not have been able to attend school.

"I was just afraid, we were afraid," she said. "If I stayed, I'd have nothing. I want a good life, I want to work, I want to do things, I have dreams too. I wish I am able to do that."

A week previously, the family had travelled through Turkey before they reached the sea to cross to Greece.

"I can't swim, and they took our life jackets from us. They told us there was a boat for us, but it was so small. We were at sea for three hours – just us, the sky, and water. Nothing else, nothing around us."

Maream doesn't know where they will be heading, but all she wants is to be in a safe place.

"I want to go to sleep, and when I wake up in the morning, I want to not fear that my husband or child is in danger, or dead."

As the refugees push on to each new leg of their journey, European leaders are struggling to find ways to distribute them among more than just a handful of host nations, particularly Germany, Austria, and Sweden.

In Hungary, which has seen more than 150,000 refugees arrive, public sentiment is less than supportive of playing any role other than guide.

Further south on the Greece-Macedonia border, where families stood in lines ready to take the five-hour train journey north, the surge of refugees fleeing war and poverty does not appear to be slowing down.

On Monday a record 7,000 Syrian refugees arrived in Macedonia from Greece, according to United Nations figures. Meanwhile, Christopher Tidey, an emergency communication specialist for Unicef, told BuzzFeed News that they expect more than 20,000 people seeking refuge to arrive in Gevgelija over the next few days.

For some gathered at the Gevgelija train station, the destination didn't matter as much as getting there.

In a polka-dot blouse with a backpack over her shoulder, Maria, a 22-year-old who left Afghanistan two months ago, stood alone among the groups of large families. Unlike most of the refugees at the camp, Maria said she had been safe at home. She decided to leave on her own after her father pressured her to marry and stop pursuing her dreams of being a writer.

"I left home because I want to keep writing," she said. "That is why I choose to run and go somewhere, anywhere — it does not matter which country, just somewhere where I'll be allowed to perform free art, to think freely."

No one in Maria's family knows her location, she said, which is why she declined to be photographed head-on. She was fearful that her father would find her.

"I don't know what waits for me out there in Europe. I've never been in Europe," she said before following a big crowd preparing to board the train. "I just hope I'll end up somewhere where I can be independent and write. I don't want mercy, just to be able to write."