"One day someone is going to hug you so tight that all of your broken pieces stick back together," James Harris wrote on Jasmine Wright's Facebook wall. Later, he posted a picture of a dozen roses with the words: "All in for you."

To someone looking at her Facebook page, it would be easy to assume Harris was dating Jasmine. But they were not in a relationship. In fact, Jasmine did not know him. All she knew about him was that he worked as a maintenance man in her apartment block.

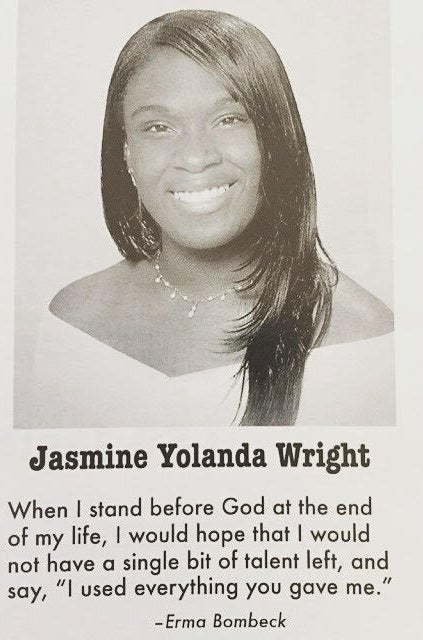

Harris regularly stalked and harassed Jasmine, and she often told friends that she felt uneasy around him. In July, Jasmine – a 27-year old Drexel University graduate from the Bronx, New York – was on her way back from the gym to her apartment block in Philadelphia. She was talking on the phone to her mother, Virginia, when she arrived home.

Her mother heard a scuffle on the other end.

The line went silent.

Jasmine was later found dead on her apartment floor. Harris, the man who had been harassing her, was charged with sexually assaulting and murdering her. After he'd been fired from his maintenance job, he had kept hold of the keys to the apartments, and had been hiding in her home, waiting for her. While Jasmine was on the phone, he sneaked up on her from behind. Her mother said she could hear the struggle before the call cut off.

Despite having been arrested for or charged with more than 30 serious offenses – including rape and murder – Harris was allowed to work in Jasmine's building, where his harassment of her was overlooked by authorities. According to a local report, another woman in the building had even changed her locks because she felt unsafe around him.

Jasmine's murder may be just one case among the thousands of instances of violence against women worldwide. But it is also emblematic of a series of gender-based killings in 2015 that have begun to force a recognition that these are not isolated incidents, but part of a larger pattern of endemic, gender-based violence that need to be addressed.

Last month, the United Nations special rapporteur on violence against women, Dubravka Šimonović, urged all member states to establish a "Femicide Watch" to tackle gender-related killings. She described violence against women as the most "atrocious manifestation" of the "systematic and widespread discrimination and inequality that women and girls face around the world."

"Women and their children continue to die as victims of gender-related killing, often in cruel ways," Šimonović said. "The weaknesses of national prevention systems, lack of proper risk assessment, and the scarcity or poor quality of data are major barriers in preventing gender-related killing of women and developing meaningful prevention strategies. These weaknesses result in misidentification, concealment, and underreporting of gender-motivated killings, thus perpetuating impunity for such killings."

Gender-related murders – often referred to as "femicide," a term used to describe killings in which the gender of the victim plays a role – differ from male homicides because they "involve ongoing abuse in the home, threats or intimidation, sexual violence, or situations where women have less power or fewer resources than their partner," according to the World Health Organization.

Jasmine Wright's murder highlighted the failure of the authorities to take action to deal with someone who was a known threat to women.

"This guy had been harassing her, and a couple of weeks before her death, she was getting really paranoid," Bri, an old high school friend of Jasmine, told BuzzFeed News. "He had been leaving her flowers and cards by her door. It should've been obvious that as a repeat offender he was a very clear threat to the public. What everyone is now asking is: How was this man allowed on the street?"

After her friend's death, Bri said she believes there is a "lack of protection" for women who are stuck in similar dangerous situations. She described Jasmine as a "really sweet girl", the "mother" of the group who gave back a lot to her community. The last time Bri saw her was two years ago, working a summer job, where Jasmine was saving to go to grad school.

"You don't see those who beat their spouses convicted until the victim is hospitalized or murdered," Bri said. "I wouldn't say I'm a hardcore feminist or anything, but I would say there is a worldwide plague of violence against women. It harms all classes, all races, all social and economic backgrounds. It's something that happens every day."

This year, reports of gender-related killings around the world have been hard to ignore. In England, a woman was killed by her boyfriend when she refused to hand over her Facebook password. Miss Honduras and her sister were killed in an attack by her boyfriend. A journalist and women's rights campaigner in Fiji was killed at home – her partner was charged with her murder. In South Korea, a man impersonated his girlfriend for two weeks after he murdered her. In Turkey, a teenager admitted to killing a woman because she "insulted his masculinity."

But 2015 also showed that the tragic murder of a woman could galvanize an entire country to sit up and call for an end to gender-based killings – and nowhere was that more noticeable than in Central and South America.

In June, following the killing of Chiara Páez – a 14-year-old girl who was buried alive at eight weeks pregnant – Argentina erupted in wave of protests that took over cities across the country. The public demands were loud and clear: Take gender-based violence seriously, and put an end to it. Thousands of people took to the streets to protest against gender violence in Argentina – more than 1,808 women have been killed in the country in seven years – using the slogan "They are killing us", and later #NiUnaMenos (#NotOneLess) on social media.

Fabiana Tuñez, executive director of La Casa del Encuentro, an NGO dedicated to women's issues, told BuzzFeed News: "This is a worldwide problem, but in Argentina in particular, there are a few structural inequalities between men and women that are deeply rooted in our culture, and violence is the vehicle for these inequalities to persist."

A month later, in July, Mexico jailed five men for nearly 700 years each for the gender-driven murders of 11 women, a historic sentence against femicide and a significant move in a country where six women are killed every day, according to the National Citizen Femicide Observatory. In Colombia, where on average one woman is killed every two days, femicide was made a distinct and legally defined crime in the same month, with jail sentences of 20 to 41 years.

Gender-related killing is beginning to be recognized worldwide, but experts say a lot still needs to be done to address the problem. Dr Aisha K Gill, reader in criminology at the University of Roehampton, in London, said it is important for countries to collect information on gender-based violence, and stressed that policies and initiatives to prevent it need to be grounded in "the reality of the experiences of the survivors of gender-based violence."

"Policy-makers need to recognize that acts of femicide occur within a general framework of the abuse of women – they does not simply happen 'out of the blue', and so need to be conceptualized as part of a broader effort to end gender-based violence," Gill told BuzzFeed News. "The most urgent requirement is to establish specialist refuges, shelters, and support services for girls and women who are at risk of femicide and other forms of gender-based violence in the countries and communities most concerned, as an issue of basic human rights."

In the meantime, women are taking the task of documenting gender-related murders into their own hands. In Turkey, local activists built a digital "wall" on which they listed the women killed in their country year by year, including Ozgecan Aslan, the 19-year-old student who was killed after fighting off a rapist in February, sparking nationwide protests. Murals of dead women and the slogan #NiUnaMenos on walls in cities across Mexico and Argentina remember and pay tribute to the lives lost to gender violence. In Australia and the UK, a project called "Counting Dead Women" collects the names of women thought to have been murdered for their gender. Compiling the names and images of the victims may not stop gender-based killing, but activists say they will continue to do so until governments around the world recognize that the responsibility ultimately lies with them.