ZAGREB, Croatia — Noona had no intention of being in Croatia.

She and her family had planned to have crossed the Serbia-Hungary border by now, and moved on towards Munich, Germany. There, they'd hoped to find a new home away from the danger they fled in Iraq just two weeks ago. But at midnight on Thursday, she was sitting on the cold floor of the Zagreb train station waiting for a train to Slovenia.

"We ran here from Serbia," the 15-year-old told BuzzFeed News, surrounded by 10 of her relatives. Her two younger sisters lay asleep on top of their bags, piled on wooden benches surrounded by sandwiches and water bottles. "We ran here, and we're very tired."

Noona and her family are some of the 17,000 refugees who have arrived from Serbia into Croatia in the last three days. The majority had traveled by foot through fields strewn with land mines to reach Sid in northwest Serbia, before crossing the border at Tovarnik and being directed by police onto trains and buses to the capital. Many of the those who have arrived in the city were transported to a nearby refugee center and registered. Others attempted to get a room in a hostel nearby. Around 100 refugees waited at Zagreb train station through the night.

When the Hungarian border shut, it drastically altered the route – from Serbia into Hungary, on to Austria, to arrive in Germany – that hundreds of thousands of people had taken in recent months. It left Noona, and the other refugees in Serbia, trapped, forcing them to carve out a new route towards western Europe.

"Why did Hungary close, why?" Noona asked. "Where could we go?"

When Hungary began its tougher crackdown on refugees along the Hungarian-Serbian border two weeks ago, it had a ripple effect on nearby countries. Soon Serbia, Croatia, and Slovenia followed suit and — despite brief instances of appearing to allow refugees to move through freely — later declared they were unable to cope with the large numbers of refugees, so they too would build their own tougher border controls.

Croatia, who earlier this week shamed Hungary for its "threatening" barbed wired fences, has since deported refugees back on buses into Serbia, the one place where there is next to no option for them to move elsewhere. Meanwhile, those fleeing are left to decipher what the latest statement from political leaders means to them on the ground.

On Thursday, Ranko Ostojic, Croatia's interior minister, said the country would not allow refugees to proceed northwards to Slovenia on their way to Germany. "Don't come over here anymore, stay in the detention centres in Serbia, Macedonia, and Greece," Ostojic said. "This is not the route to Europe."

As countries across Europe continue to make U-turns on their refugee stances and seal borders to divert refugees into neighbouring countries, only one thing remains consistent: the people, caught tangled in Europe's squabbling game of cat and mouse, who still remain in search of safety.

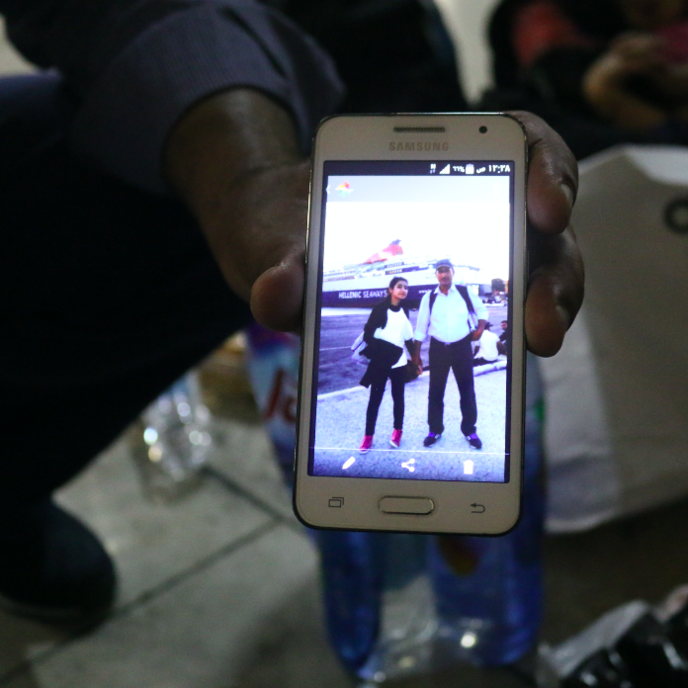

In the station, Noona took out her phone and showed photos of the long route they had taken so far. There were pictures of the plane the family had flown from Iraq to Istanbul, a boat in Athens, and the inside of a train going through Macedonia. Among them were photos of life in Iraq before they were forced to flee.

"We are going to Germany through Croatia because there was death in Iraq," said Noona. "My house was burned down. No school, no house, no hospital, nothing. What we had there is finished."

After a long night, the Zagreb station began to bustle by morning. Locals boarded trains with suitcases in hand while refugee men, women, and children looked on, unsure of whether they'd be able to pass through to their next biggest hurdle: the Slovenia border.

Overnight, Slovenia had allowed a first batch of 150 refugees to enter from Croatia by train, where many were transported to a refugee centre in Postojna in the west of the country. However, a number of reports of coaches and trains being turned away and returned to Croatia at the Slovenian border surfaced, prompting many at Zagreb station to panic.

Whispers that the Slovenia-Croatian border has closed completely circulated around the train station.

"Can you check your phone?" one Somali man asked a volunteer. He sat with five friends who had also fled their home country, citing the economy and war as among the many problems they faced at home. "Maybe you can find out for us on your phone about Slovenia. Slovenia — that's where our problem is right now. Now we don't know if the border is open. No one knows."

At the Zagreb station, families and groups of friends sat under trees by the station, taking shade from the heat. Basma, 27, was there with her son, Adam, and her husband. She met her husband in college five years ago, and they got married two years later. They left Baghdad and had traveled to Greece — where they were at sea for seven hours — through Macedonia and on to Serbia, where they were turned away at the Hungarian border.

"My name means 'smile', and you know, I'm smiling," Basma said, laughing. "We've been travelling for so long. We've been sleeping on the floor... I'm sorry, I haven't brushed my hair for weeks!"

A large number of the refugees arriving in and out of Zagreb were from Iraq. Basma said that although she loved Iraq, she left because since 2003, her country "has been killing, threatening, and abducting people."

"We are not going away to be safe from Iraq," she stressed. "We are going away to be safe from war. We only left because there is no peace, and no peace of mind."

Police patrolled the station, and Basma ran around with her son, playing among the crowds. "One day, when he's older, he's going to ask me: 'What about Iraq?'" she said. "I hope he then says, 'Thank you for saving me.'"