CENOVÍ, Dominican Republic — Emely Peguero had been missing for less than 24 hours when her boyfriend decided to hold a press conference. Peguero was 16 years old and five months pregnant when she disappeared. Marlon Martínez, her boyfriend, had last seen her on the morning of Aug. 23, 2017. As the hours passed that day, Martínez saw her name start to be talked about on social media and WhatsApp groups. Friends and family said that it wasn’t like her to not reply to text messages or ignore phone calls, and they asked where Peguero might have gone. By the evening, it became clear no one had heard from, or seen, Peguero since Martínez last saw her.

By the next morning, and with still no word from Peguero, Martínez knew he had to do something. Martínez’s mother, Marlin, wanted to help her son. As a senior, well-connected civil servant, she was a powerful figure in the Dominican Republic. Mother and son invited two local reporters to their home in the town of Cenoví, a few hours north of the capital, Santo Domingo, so they could publicly express their concerns over Peguero.

“Emely, no matter where you are, please, we are waiting for you with open arms.”

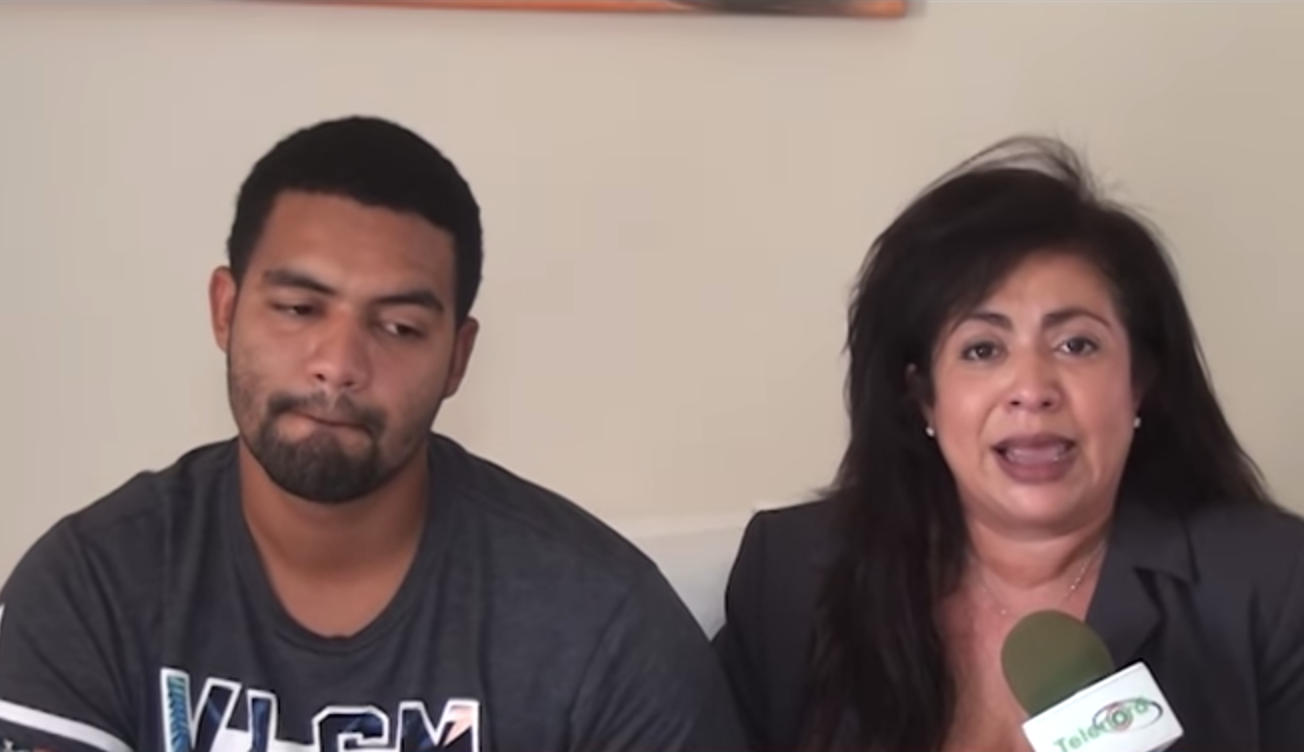

Martínez and his mother led the reporters into their living room. Dressed in a gray T-shirt, Martínez appeared less formal than his mother, who wore a dark suit jacket. When the cameras were turned on, they focused on him. Looking at the floor, Martínez began to describe the last time he saw his girlfriend. After several minutes, he finally looked into the camera, pleading for her to come back home.

“We’ve had problems, but problems that are common to all couples,” he said. “We accepted her pregnancy. We said we’d continue forward. ... I want to now make a public announcement: Emely, no matter where you are, please, we are waiting for you with open arms.”

Martínez stopped speaking, staring back down at the floor. He threw his head into his hands, and sat silently, as the reporters behind the camera began to ask questions. After a moment of quiet, the shot panned out to show his mother, who then began to talk.

“She was already a part of us, and she was my son’s girlfriend,” she said, before correcting herself, “is the girlfriend of my son. She was five months pregnant, and when we found out, we gave her our support.”

She began to sob. “I understand how her parents feel,” she said, with a slight tremble, “and we feel even worse. Wherever you are, Emely, don’t make us suffer any more.”

Peguero and Martínez had known each other since they were children. They grew up together in Cenoví, on the outskirts of the city of San Francisco de Macorís, in the mid-2000s, playing with other local kids in the streets of their hometown.

Peguero’s family lived in a small, quaint home with shuttered windows, a flat roof, and a painted mural of a butterfly on the front-facing wall that had faded from the sun. Her parents struggled to support her and her three older siblings, juggling low-paid part-time jobs. Martínez lived across the road from Peguero, but they might as well have been in two different worlds. He lived in a grand, modern villa, closed off by a large front garden and gate. Martínez was born in New York in 1998 and was raised by his mother and stepfather in the Dominican Republic. His family could afford holidays and lavish gifts, and sent him to an expensive school out of town. As the years passed, Peguero and Martínez lost contact, and only saw each other in passing.

In his late teens, Martínez rekindled a connection with Peguero, and the pair started to date. Martínez was 18 and Peguero just 15, below the age of consent in the Dominican Republic, which is 18. Peguero’s parents were supportive of their daughter nonetheless, but they didn’t warm to Martínez’s mother, who they thought was judgmental of their family.

Peguero was also uncomfortable with the difference in wealth between the two families. She worried she was a burden on Martínez and his family, and that his mother didn’t want him to date her. She told Martínez about her concerns, but he reassured her, saying that he didn’t mind that she was poor.

Peguero got pregnant in early 2017. As a minor, she was worried at first about having a baby. Catholicism played a big part in her family life, and abortion went against her religion. She would often attend church summer camps and had a framed image of Jesus on her wall. She also knew taking abortion pills or getting a back-alley abortion could land her in jail or even kill her.

She knew taking abortion pills or getting a back-alley abortion could land her in jail or even kill her.

In the Dominican Republic — a largely Catholic country — abortion is strictly illegal. The last 20 years has seen the introduction of stricter laws on abortion across Central America, and it was criminalized in the Dominican Republic in 2009. In 2012, the country introduced prison terms for people who assist with abortions, including medical staff, but also friends and relatives. Today, it is one of only six countries worldwide that bans abortion in all circumstances. Last year, the UN Development Programme found that nearly a quarter of girls between the ages of 12 and 19 in the Dominican Republic have been pregnant, 34% higher than the average for Latin America and Caribbean countries.

There is currently a bill before the Dominican Congress to decide whether to decriminalize abortion in three cases: when the mother’s life is at risk; when the pregnancy is not viable; and in cases of rape and incest. While abortion rights campaigners are hopeful lawmakers will approve this new proposal, in a country where the Catholic Church holds so much power, it seems unlikely.

After talking with her mother, Peguero decided to keep the baby. Martínez’s mother, however, wasn’t thrilled at the idea of her son becoming a father so young, and with a poor girl from the family next door. As a prominent member of the Dominican Revolutionary Party, an important ally of the ruling political party, and deputy director of passports in one of the country’s main districts, she held a lot of power locally.

Soon after Peguero disappeared, suspicion turned to Martínez and his mother.

People who had never met the couple began to question Peguero’s relationship with Martínez. Rumors swirled around about the poor girl who had gone missing — and the wealthy, powerful family of her boyfriend.

It was to counter those stories that Martínez — by then 19 — and his mother decided to hold the press conference. He told the gathered video journalists that he had not seen Peguero since he dropped her off at a gas station on the morning of Aug. 23, when he said he saw her get into a car to take her to a prenatal appointment.

But rather than allay the public’s suspicions, the press conference only added fuel to the fire. Why, people asked, did the mother and son invite reporters to their house rather than go to the police, as Peguero’s parents had done? Why did they keep referring to Peguero in the past tense? “When a person is lying they look to the floor, and he’s only looking at the floor,” read one YouTube comment under a copy of their taped conference. Another read, “Not only did she say she was my son's girlfriend, but she also said she was part of us, she was 5 months pregnant!” Some people even made their own YouTube videos, running through conspiracy theories about the mother and son.

With all the suspicion surrounding him, Martínez went to the Peguero family home for the first time since she went missing. It was there that Martínez decided to hand himself into the police, realizing they would likely arrest and question him soon anyway. Martínez agreed for the family to take him to the police station, where he was arrested as the main suspect in her disappearance.

With all the frenzied rumors on social media, growing desperation from Peguero’s family, and mounting pressure on Martínez, one thing still remained unclear: Was she still alive?

Five days after her disappearance, local police made a breakthrough. On Monday, Aug. 28, they traced the geolocation of Peguero’s phone to Martínez’s mother’s apartment in San Francisco de Macorís, where she stayed when she worked away from Cenoví. When police searched the apartment, they found blood spatters on a mattress.

Two days later, a security guard at the apartment block said that he had seen Martínez carry a sack out of the building. He also said Martínez’s mother had asked to see the footage, and that later, it had been stolen. “I don’t know if the lady took it,” the guard told police. “I only know that when she saw the video, she put her hand on her head and started screaming.”

“I only know that when she saw the video, she put her hand on her head and started screaming.”

Public anger continued to grow — much of it directed at Martínez’s mother, with many seeing her as the evil female mastermind behind Peguero’s disappearance. Across the country, people believed she would use her influence and wealth against a poor family in order to protect her son. On Wednesday, Aug. 30, the same day the security guard spoke to police, she handed herself into the authorities. Her lawyer insisted she did this only to cooperate with the police. During her arrest, a reporter asked her if she had been involved in Peguero’s disappearance. She replied: “I’m not an accomplice — I never would. I only acted like a mother.”

Finally, the pieces began to fall into place. Later that day, Martínez made a confession to police, and the Peguero family’s worst fears were confirmed: He admitted to killing her. It was the first time the police knew for sure that she was dead.

Martínez told police that he left her body in a local landfill, and the police drove him to the site. Angry crowds gathered around the car, and officers fired shots into the air in an attempt to drive them away. As Martínez sat and waited in the car, authorities searched and searched, but after seven hours, they gave up: They couldn’t find her body.

The next morning, residents of Peguero’s hometown erupted in anger. At 9 a.m. they walked into the roads, stopping traffic and calling for Martínez to tell the police where he had hidden her body. They burned tires, threw rocks, and threatened to destroy Martínez’s house in Cenoví. Police officers dressed in riot gear tried to disperse the growing crowds by throwing tear gas at protesters.

Later that day, across town, Peguero’s older brother, Eugenio, received a flurry of messages on WhatsApp, from people telling him they’d heard that a body had been discovered in the province of Espaillat, about a one-hour drive from Cenoví. As the sun set and police descended on the town, Peguero’s brother and other relatives frantically drove to the site. Crowds of people had gathered in the darkness, illuminated by the blue and red of flashing police lights. When the family arrived, they saw people standing around an abandoned suitcase by the side of the road. At 8 p.m. on Aug. 31, Peguero’s decomposing body was found inside.

By this time, the story of the missing girl had spread around the world. Peguero trended on Twitter, and photos of her dressed in a red traditional Dominican dress flooded Instagram. Posts about her were shared and liked hundreds of thousands of times around the world, and in an effort to rally support, Peguero’s family started a hashtag campaign called: “We Are All Emely.” It caught the attention of the rapper Cardi B, who is of Dominican descent, who shared a post about Peguero to her 23 million followers. “What would you do to keep a clean image and reputation?” she wrote in the caption. “Make a 15 year old girl get an abortion and kill her so they don’t find out your 19 year old son got a minor pregnant?” Dominican celebrities also spoke out, including the singer Sergio Vargas and baseball player Starling Marte, who tweeted that Peguero was a victim of “machismo.”

While images of Peguero went viral, her family was dealing with the harsh reality of what she had suffered. The police and forensic reports about her death — compiled between September and December 2017 and seen by BuzzFeed News — detail the scale of the violence inflicted on her. Peguero experienced internal bleeding, believed to have come from a botched abortion attempt. She also suffered a blunt-force blow to the skull.

After all, who would go looking for a poor missing girl?

Police had since learned that Martínez didn’t take Peguero to the gas station on the morning of her death, as he had told reporters. Instead, he took her to his mother’s empty apartment. The prosecution told the court that Martínez forced her to drink an unknown liquid to induce an abortion, causing the internal bleeding, and then killed her by hitting her over the head. The press and many people on social media speculated that a local doctor may have advised Peguero to get an abortion. However, the doctor later held a press conference where she denied the accusation and said she had only served as a gynecologist when she met with Peguero once.

After Martínez killed Peguero he put her body in a sack, carried it down the stairs and out of his mother’s apartment block, and threw it from a bridge in Cenoví onto the soil below. The prosecution argues that Martínez then called his mother to tell her what he had done, and to ask her to help him. In the early hours of Aug. 24, according to the police, she discussed with her son and two accomplices (her brother, Martin, and a friend, Simón Bolívar Ureña) what to do with Peguero’s body. Angry at her son’s failure to hide the body in a discreet place, she insisted he move it. Martínez then collected Peguero’s body from under the bridge, stuffed it into a suitcase, and dumped her by the side of a road, in a town one hour from Cenoví.

In May, Ricardo Reyna, the defense lawyer for Marlon Martínez, said that his client was not guilty of murder. Instead, he argued Martínez participated in Peguero’s abortion procedure, which accidentally led to her death. Reyna has argued there is “no evidence” to suggest Peguero’s death was murder.

Latin America has some of the highest rates of femicide in the world. But even in a country that had at least 170 reported cases of femicide last year alone, the brutality of Peguero’s murder, and the implication of a public official, has shocked the Dominican Republic. But it also forced it to consider how its own draconian laws for women played a role in her death. In 2012, Congress approved sentences of up to three years for women who have an abortion and between four and 10 years for anyone who helps someone get the procedure. If Martínez had not attacked Peguero, but had instead been found to have helped her get an abortion, he would have been the one to face a harsher sentence. The logic of Dominican law made it seem a better idea for him to kill his girlfriend, and remove any trace of her altogether. After all, who would go looking for a poor missing girl? According to local reports, while the police were searching for Peguero’s body they found two other dead girls, both aged 18.

Martínez and his mother, Marlin, have been held in preventive detention since late 2017, as they face pretrial deliberations. Trial proceedings were due to begin May 18, but the court delayed them until June 11. Martínez faces up to 30 years in prison for the murder of Peguero, and his mother, accused of complicity in the concealment of Peguero’s corpse, faces up to 20 years.

The lawyer for Peguero’s family, José Martínez Hoepelman, believes that once Martínez’s attempt to force the abortion had gone wrong, he thought it would be better — safer — to kill Peguero and make her body disappear than to take her to a hospital and risk imprisonment. “He didn’t expect her body to be found,” Jose said.

The brutality of Peguero’s murder, and the implication of a public official, has shocked the Dominican Republic.

Hoepelman said Martínez and his mother planned how they’d bury Peguero’s body at around 1:15 a.m. on the morning of Aug. 24, as her body sat in the trunk of their car outside their family home.

Hoepelman has built a kind of cultlike status in Dominican media and regularly appears on television and radio to speak about Peguero’s case. His passionate speeches hold the attention of the tiny courtroom, including one that went viral last year, in which he directly addressed Martínez’s mother: “Marlin, in the Dominican Republic we are not afraid of you! Face your charges over the murder of Emely Peguero and your ... grandson, and yet to be born! Defend yourself from that! Not me!”

In the nine months since Peguero’s death, each week has brought fresh drama to the pretrial proceedings. Family members have boycotted some hearings, multiple defense lawyers have dropped out, and a suspect who authorities believed to have fled the country was arrested at the airport. In April, Peguero’s father, Genaro, was arrested after he allegedly tried to bring a firearm into the courtroom.

Martínez’s mother is described as the overprotective, villainous mother who didn’t want the baby, while her son is depicted as an easily manipulated fool. Her wealth and powerful connections have only exacerbated the public’s anger toward her. During the early weeks of the trial, members of the public threw rocks at her, and since then she’s worn a bulletproof jacket and helmet in court, with armed guards surrounding her. Her son hasn’t needed any such protection.

There are videos on YouTube dissecting her every move, including one that’s racked up more than 150,000 views. It zooms in on a photo of her smiling, with the words: “This woman shows that she does not have any kind of conscience for what she did; the woman is a demon.”

Peguero’s bedroom remains in the same state she left it in before she died. Red paper hearts are stuck on her headboard and neon pink curtains drape her window. A photo of Peguero in her school uniform hangs on the wall, framed by a Hannah Montana collage. By her bedside table sits a pile of handmade bracelets, a small statue of Jesus, and a framed photo of the pope. Her clothes are stacked up in the wardrobe, alongside her collection of stuffed toys. The only new item in Peguero’s room is a collage of photos and messages commemorating her death, made by students at her school.

Her mother, Adalgiza Polanco, hesitated before pushing the bedroom door open. It was late spring, seven months after Peguero died, and she rarely went inside, mostly keeping the room locked. She separated from her husband shortly after their daughter’s murder and moved in with her parents down the road. Momo, the family’s small terrier, rushed past her legs, through the crack in the door, and circled the floor. Momo, she said, would always run into Peguero’s room when she arrived home from school, yapping and pouncing up on her legs. “When she first went missing, I waited here for her to come back,” Polanco said. “By the second day, I thought she was dead.”

Despite Martínez’s confession, Peguero’s parents place more blame and anger on his mother, Marlin. “She lived in an empty world,” Polanco said. “She didn’t want her son to have a baby with a poor person.”

Physical reminders of Peguero are everywhere in their hometown. Her face is plastered on several billboards, on the front pages of newspapers, and on car stickers. Girls at her school say her murder was a reminder of just how dangerous it is to be a girl or a woman in the Dominican Republic.

Peguero’s best friend, Sharilenny Morel Peña, is timid and soft-spoken, and nervously smiles when making eye contact. She said Peguero was a chatty, confident student, who would fiercely defend her and other friends. “She wouldn’t look for trouble,” she said. “But she stood up for herself.” They spent a lot of time together outside of school, and would often cook spaghetti at Peguero’s home. Morel Peña remembers how Peguero wrote her a Valentine’s Day card in 2015. In the card, Peguero thanked her for being her friend and “putting up with her.” She told Morel Peña she was like a sister. Morel Peña wrote her a letter back, telling her she was thrilled to have found a good friend in Peguero.

Morel Peña said she had struggled with depression before, but since Peguero’s death, she has been overwhelmed. She walked to the garden area near the back of her school grounds where she and Peguero used to run to between classes and after school. Here, they’d complain about homework and gossip about their friends. She liked it here because it was just the two of them alone. Morel Peña said Peguero always helped pulled her through difficult times. But now, she has no one. “I wish she was still here to help me. I wish it was me instead.” ●

Rossalyn Warren was a 2018 Adelante Latin America Reporting Fellow with the International Women’s Media Foundation.