Paige worked in corporate America for several years before deciding at the beginning of 2020 to switch to a career she found more meaningful. When the pandemic hit a short time later, she second-guessed her decision, but the crisis also made her feel “more compelled to rise to the occasion.” She completed virtual training. Paige — who spoke on the condition that only her middle name be used — started her first job as a teacher at an under-resourced Dallas-area middle school in January 2021. The district was using a hybrid classroom model, blending remote and in-person instruction. Paige had the advantage of a previous career that prepared her for the technological headache. She felt she was able to build constructive relationships with her students, especially the roughly 30% who came to school in person. Though her subject, reading, is a perennial testing priority, she was liberated from test pressure since states were given the option to waive the usual battery of exams that year. In hindsight, her first few months of teaching were “breezy and manageable” in comparison to what came after.

On the first day of the 2021-2022 school year, all students were back in person. The sixth-graders she taught hadn’t been in full-time school since the fourth grade, and Paige saw the same kind of problems that many teachers have observed this year. Many were struggling. “These kids have gone almost two years without structure and following rules and routines and interacting with their peers,” she said. They lacked social skills and behavior problems ran rampant in the school, which didn’t have enough staff to manage them. The students were also behind on academics, but the district had returned to pre-COVID expectations for benchmarks; Paige’s students were “heavily, heavily tested” in four core subjects, undergoing testing twice a month in each. Catching them up was nearly impossible given the challenges. She says an administrator told her to focus on kids most likely to perform well on tests to maximize funding return.

Each day, Paige saw the strain in a tangible way: She had 28 kids on average in her classes. Her classroom had 17 desks. She complained to her school’s administration, who told her they were still adjusting schedules to even out the class sizes. Paige improvised. She didn’t want students to “feel distressed,” she said. She managed to wrangle four extra chairs and gave clipboards to all the students who didn’t have a desk. By the third day of school, after “raising hell,” she was given three more desks. But she didn’t have enough for every student in her classroom until January — a full five months after the start of the school year. By then, during the Omicron wave, teachers at the school had frequently been out sick, and the district had a major shortage of substitute teachers. The school managed it by spreading out students to other classrooms. One day, Paige saw dozens of kids just wandering the halls. “How is any learning even supposed to happen, or order supposed to happen if you have kids sitting on the floor?” she said.

Teaching has always been a demanding job. It’s a cliché that many teachers burn out within five years of starting; the commonly cited statistic is University of Pennsylvania researcher Richard Ingersoll’s finding that between 40% and 50% of them do so. Teaching “has had recruitment and retention problems, and that’s perennial,” Ingersoll told me. But this moment may be unprecedented. Though complete national data on the pandemic-induced teacher shortage isn’t yet available, Ingersoll said, the anecdotal and statistical trends he’s seen so far make him think “this could well be worse” than any shortage he’s examined in his career studying the teaching force. When Paige quit her job, she was the fifth teacher at her school to do so mid-contract. Over half a million public school educators left the field during the pandemic, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data; a recent National Education Association poll of its membership showed that 55% of them were planning to leave. Forty-nine percent of teachers in an American Psychological Association poll conducted between July 2020 and June 2021 said they wanted or planned to quit, as well as large percentages of school staff and administrators.

Rising costs of living were already outstripping teacher salaries before the pandemic, a key factor behind the teachers’ strikes in several states that took place in 2018; teacher pay has always lagged behind other college-educated professions, though they’ve traditionally received good benefits and pensions. Now, to many teachers, the tradeoffs look less worth it — even if they were to get a raise. School districts are desperate for new teachers, in some cases offering unprecedented signing bonuses to lure applicants — and still not filling vacancies. Some districts are allowing teenagers fresh out of high school to substitute teach; I spoke to a 19-year-old college student in Connecticut who started subbing soon after graduation, including at the school she had recently graduated from.

I spoke to a 19-year-old college student in Connecticut who started subbing soon after graduation.

This winter, I interviewed dozens of teachers across the country, from all kinds of districts and at all levels of experience. Most of the teachers worked at public schools, though a few were private school teachers or charter school teachers. I contacted many of the teachers through the r/Teachers Reddit board, which has over 300,000 members.

In those conversations, it became clear that the pandemic didn’t simply create but heightened problems that existed long before. Parents struggled to improvise childcare in the absence of in-person school, a situation that strained families and exacerbated inequality; some kids had quiet homes and access to Wi-Fi, some did not. Some families could form learning “pods” and afford extra instruction for their children, while most could not. Remote learning caused a severe setback in many kids’ academic progress and damaged the mental health of some. It also highlighted the fact that schools serve many purposes beyond academic learning, like providing meals for kids and identifying children who qualify for social services or special education. The debate over school closures devolved into one side calling teachers lazy and narcissistic, and the other side accusing parents of selfishly wanting free daycare while they worked. Once teachers’ unions got involved and began pushing against reopenings in the summer of 2020, the vitriol boiled over on both sides. Democrat-run states where teachers’ unions are strong tended to delay reopening, while Republican states opened. Some teachers in red states I spoke with had been teaching in person since the fall of 2020.

Despite these wide geographic and logistical differences, however, nearly all of the teachers I interviewed spoke about similar problems in their schools that touch every aspect of our culture and society, from technology dependence to stats-obsessed bureaucracy. Teachers described increasing pressure from multiple angles. They’re dealing directly with the ways phones and technology have changed the classroom environment. They’re dealing with kids who were out of school, sometimes for years, and are readjusting to social interaction every day. They’re dealing with an increasingly political and surveilling approach to curriculum from outside, and longstanding budgetary and bureaucratic demands from above.

The breakdown of teaching, I came to understand, has been accelerating in plain sight from well before the virus hit. But its aftershocks will be felt long after the virus has faded.

As the Omicron variant surged all around him, Martin Urbach was teaching his tenth-graders at Harvest Collegiate, a high school in downtown Manhattan where 67% of students qualify for free or reduced lunch. A group of them sat in the fluorescent-lit classroom finishing their lunch between sessions of a restorative justice workshop Urbach hosts. Urbach put me on Zoom so I could speak with him and the kids. All wore masks, which made it hard to tell who was speaking at any time. Though the sophomores were back in school, their high school experience had so far been anything but normal. Ninth grade was remote, and masking up throughout the (abbreviated) in-person school day wasn’t exactly what they had dreamed of. “I feel like we haven’t had any type of real high school experience,” said one of the students. “Most people didn’t really get that freshman experience of being in school meeting people,” said another. “And now we’re in the building but it’s still not that authentic high school experience that I would really love to have.”

During the surge, the school went into a kind of war footing in an attempt to control it, canceling electives and letting students leave at 12:45 if their parents allowed. One of Urbach’s students told me that one day he walked through the halls for 45 minutes after the 12:45 bell and didn’t see a single teacher or sub. He alerted one of the school’s social workers, who told him to just go home. None of the students blamed teachers for what was going on. “I feel like it's really stressful for all of us, especially teachers,” one said.

The Zoom era, far from relaxing, was isolating and arduous. “Last year, the loneliness and teaching on Zoom all day long really kind of destroyed parts of my spirit,” Urbach said. The physical challenges of teaching in person with COVID restrictions this school year had been daunting, though — hard to communicate with students while everyone is wearing a mask, hard to hear over the constant hum of air purifiers. Urbach got COVID right before the winter break. He’s angry at the system that has left schools in such a state. But despite it all, he said, “I love getting to spend time with the young people and just getting the connection that only in-person school can happen.”

Urbach has been teaching for 17 years, five at Harvest Collegiate. Of all those, even after the crisis of 2020, “this year has been the most exhausting year for my whole career,” he said.

Connection with students, many teachers say, isn’t what it used to be. The emotional and behavioral crisis among American kids has become so obvious that President Biden addressed it in his State of the Union speech.

First, there’s the technology. Smartphones and laptops aren’t new, and schools have had to contend with distracting devices for years now. Ken, a high school teacher in Northern California, noticed a shift around 2010 when smartphones became omnipresent. Ken teaches computer programming, and when he started out 20 years ago, his students loved learning about how a computer works, seeing inside the box. But around that smartphone inflection point, he saw their interest fade away. Why bother learning the nuts and bolts of computing when everybody had a super-powerful computer in their hands at all times?

Now, though, their withdrawal has grown more severe. “I have students post pandemic who will sit and just stare at the screen,” he said. “They’re so disengaged from everything.”

“I was watching one student make their way through the entire third and fourth season of Bojack Horseman.”

Teachers describe swaths of kids nearly anesthetized by technology, socially limited, and often displaying disruptive behavior. It’s not only teaching them that’s hard — it’s reaching them on any level. The screen dependence that preceded the pandemic seems to have gotten worse during it, turning students across America into TikTok mainliners. Everyone seems to have given up on managing it.

“Five years ago, it was an issue in that it was kids just texting each other,” said M., an art teacher in Northern Virginia who requested going by her first initial to speak freely. Now, she says, she’s observed more passive content consumption in lieu of communication. “I was watching one student make their way through the entire third and fourth season of Bojack Horseman,” she said.

The way teachers describe their hyperconnected yet disengaged students is reminiscent of the British writer and critic Mark Fisher’s descriptions of his philosophy students at a continuing education college in his 2009 book Capitalist Realism. Fisher noticed that the teenagers in his classroom wallowed in a state of what he called “depressive hedonia,” glumly and constantly seeking an instant gratification that never translated to true satisfaction. The students displayed a “twitchy, agitated interpassivity, an inability to concentrate or focus.” Even in 2009, like Ken observed, personal devices had already become too mighty for teachers to compete with in the classroom. The system had conditioned the students to view education like any other consumer service, and teachers were thus “caught between being facilitator-entertainers and disciplinarian-authoritarians.”

“They’re just waiting for something. And I don’t know what that thing is that they’re waiting for.”

This tension nowadays starts early as screens become a part of children's lives at younger and younger ages. “We’re competing against all the devices,” said Yvonne, a second-grade teacher in southern Illinois who has been teaching for over 30 years. “I can think of good things to say about technology,” she said; over the break she was able to keep in touch with one motherless girl in her class on Google Classroom, for example. “But I can see that sometimes it’s hard to keep a child engaged.” Increasingly, her students are given unrestricted access at home to YouTube, viewing material she doesn’t think is age-appropriate.

TikTok is seen as a particular curse, given its addictive quality and ability to spread new fads rapid-fire, like the “devious licks” TikTok challenge that briefly made it trendy to vandalize school property.

“TikTok is just wrecking these kids’ attention span,” said Joe, a high school history teacher in upstate New York who has also taught middle schoolers. “You always have to teach in 15-second intervals for the youngest; for the oldest, it’s a little different.” Activities that used to be considered a treat, like watching a movie in class, now get rejected as boring. “If I show them a movie, they don’t want to watch it,” said James Stanley, also a high school history teacher, in Killeen, Texas. “If I have them do activities, they don’t want to do it. If I have them do notes, they don’t want to do it… they’re just waiting. That’s it. They’re just waiting for something. And I don’t know what that thing is that they’re waiting for.”

Then there are the other, more serious challenges teachers are seeing.

“Astonishing,” “terrible,” “off the wall”: These are just some of the ways teachers describe the behavior issues they are seeing in their schools. These range from a non-threatening though puzzling unconcern for the bare minimum — raising one’s hand, not walking around the school or classroom during lessons — to more severe disruptions like violence, bullying, and breaking things. The pandemic seems to have exacerbated these issues, though they’ve always been an under-discussed fact of American education, a fact Biden also acknowledged in his State of the Union. A third of teachers polled by the American Psychological Association reported receiving verbal harassment or threats from students in the 2020-2021 school year, while 14% said they’d been the victim of physical violence.

A Georgetown analysis of how schools have spent federal COVID relief funds found that about a third devoted money to social-emotional learning, or SEL, an increasingly prevalent concept in education. The idea behind SEL is to promote emotional management and social skills as part of the school day, not separate from academics. Its proponents say it has a measurable impact on classroom behaviors and academic performance. Opponents say the method overly de-emphasizes academic learning and infringes on the home and family’s purview.

It’s clear that kids need help that goes far beyond their studies, and the SEL push is an attempt at addressing this. It’s often coupled with new discipline frameworks, like restorative justice practices, and an emphasis on giving kids “grace” in the wake of two traumatic years. While this all sounds enlightened and helpful, and can be when applied skillfully, teachers say that these concepts often prove counterproductive in practice. Schools have increasingly removed many of the once-standard consequences for misbehavior like detentions, suspensions, and even being sent to the principal’s office, except in extreme situations. Many schools have de facto stopped trying to keep kids off their phones in class. The absence of consequences, many teachers I spoke with said, has undermined their authority, led to disorderly and even unsafe classrooms, and hampered learning overall by diverting lesson time to classroom management.

H.R., a teacher in rural Missouri who teaches first-years in English and Spanish, described her students as around a sixth-grade level academically, and even less mature than that behaviorally. Disruptions are frequent in her classroom, along with talking back and constant requests for special exceptions on missed work. After a year of “rough classes,” H.R. is tired of hearing about grace.

“I hate that word,” she said. “I mean, nobody gave us grace. So what about us? And we gave them too much grace, and now these are the consequences of our actions.” Her students are finally “learning how to be in school,” she said, but “it was touch and go.”

“I don’t know how many fights I had break out in my class,” said Darby McNally, a former middle school teacher in Atlanta. “Like physical fights, like kids bleeding in my classroom. And not just me, multiple teachers around me as well.” McNally felt she had no backup from her administration, who refused to impose consequences in an effort, McNally surmised, to avoid recording so many disciplinary incidents. The result was that “I really was not able to teach” because of the constant disruptions in class. “I really am knowledgeable of the subjects that I’m teaching and I would be able to, in the right circumstances, provide knowledge and care to these kids, but the environment was just not conducive to that whatsoever,” she said. McNally left at the end of the first semester, paying a $1,000 fine in order to quit mid-year.

School districts face a complicated balancing act when it comes to severe behavior issues: negotiating the needs of the student, how it affects their peers, their parents’ reaction, and the system’s legal obligation to provide an education for every child. The complexity often feeds inertia, keeping students in an environment that might not be beneficial for them nor their classmates while making a teacher’s job harder.

Even the school administrators one level above teachers often have little say when it comes to discipline, even in cases of serious violence. “They won’t let me expel for fighting unless they have multiple fights and the fights get severe,” said Donald P., a vice principal in Arizona. “I’ve had some severe fights and I’ve pushed to get the kid expelled and they won’t do it. I actually have an easier time having the student arrested than expelled.”

Lydia Echols teaches middle school English in a district outside of Dallas. Though it’s her fourth year teaching, it’s her first in this district, which is smaller than her previous one. At the beginning of the school year, Echols’ school held a parent-teacher night, which she felt went well. She thought the parents were “lovely” and was excited to meet them. So she was surprised when a student the next day told her “my parents don’t like you because you’re too liberal.”

“I don’t remember ever bringing up anything political,” Echols said. “I don’t remember being anything other than myself that night. Apparently, something about me that’s too liberal for these parents. And they don’t like me because of that, even though I completely adore their child.” Echols was also wary. “That’s one thing that could get you in trouble here,” she said. “You know, ‘you’re being too political or or you’re being too liberal by introducing my child to this text.’”

To avoid such impressions, Echols’ new district places a heavy emphasis on teachers staying within the strict bounds of the curriculum, to a degree that struck me as counter-productive. When I spoke to Echols, she was teaching her students The Diary of Anne Frank, a mainstay of middle school curricula nationwide. She’d been directed to downplay the Holocaust part. “When we were instructed to teach this, they told us explicitly you’re not history teachers, so don’t go too deep into the history of the Holocaust in how it touches on Nazis, neo-Nazism, Holocaust deniers, things like that, and we’re not allowed to broach those topics in a realistic way where it makes the kids sit up and pay attention,” she said.

“As an African American woman, I am all for social and emotional justice and learning for these kids who are going into a world where they are going to have to face these issues,” Echols said. She has wanted to teach The Long Way Down, a well-received 2017 young adult novel about gun violence told in verse, but she hasn’t been able to get permission. “Anything that looks like, smells like, tastes like critical race theory to whoever is in charge is not allowed. That’s why we can’t go anywhere with a curriculum.”

A few hundred miles away in rural western Missouri, H.R., the ninth-grade English and Spanish teacher, is working in an environment she described as paranoia-inducing when it comes to teaching anything with a whiff of political sensitivity.

“I cannot for the life of me ever teach something that has to deal with like, social justice. Or anything that highlights you know, like, basic human rights like LGBT and things like that,” she said.

H.R. has felt the need to tread carefully after a class discussion of the novel Ender’s Game offended a few students who didn’t like hearing about the atheist society depicted in the book. She worries constantly that a parent will try to get her in trouble for something like that. Teachers like Luis, a sixth-year high-school teacher in Scottsdale, Arizona, have learned what kind of material will generate parent complaints: in Luis’ case, the Rudolfo Anaya novel Bless Me, Ultima, which some parents opposed because it involves witchcraft.

Conservative activists have pushed the specter of critical race theory in schools into the mainstream of political debate over the past two years. Though the term itself refers to a theory of systemic racism encoded in the legal system that originated among scholars in the 1970s, the right has used the term to attack anything that seems too woke on race or diversity. Critics have portrayed it as a sinister, anti-American ideology being smuggled into children’s heads on the taxpayer dime.

More than one teacher I spoke with scoffed at the idea that they could teach students about critical race theory even if they tried; it’s enough of a challenge as it is to get them to pay attention at all. “I could teach basket weaving, and they still wouldn’t learn it,” said Joe, the history teacher in upstate New York. “Let alone these massive, you know, critical race theory beliefs.” The furor has powered a national wave of fraught, often unruly school board meetings and motivated voters in key races like last year’s Virginia gubernatorial election, powered by conservatives.

Republican state lawmakers around the country have been introducing bills designed to prevent classroom discussion of institutional racism that would directly impinge on teachers’ pedagogical autonomy. These range from bans on specific curricula to sweeping injunctions against teachers bringing up certain topics. A new law in Florida, which opponents have called the “don’t say gay” bill, outlaws any instruction about sexuality or gender until fourth grade or “in a manner that is not age appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.”

So far, these endeavors have been a mixed bag; bills attempting to ban the teaching of “divisive concepts” recently failed to pass in Indiana and South Dakota. But the movement has contributed to an atmosphere of censoriousness around teachers. So have efforts to increase “transparency” by filming teachers or requiring schools to post lesson plans and curriculum materials online ahead of time.

According to Ingersoll, the controversy, however fervent, is just the “latest manifestation” of a “long-standing debate” about curriculum dating back at least to the 1925 Scopes Monkey trial. “These are people's children,” Ingersoll said. “And so there's a tussle. You know, who gets the final say in what they're taught and how they're taught?” The current situation also reflects the persistent tendency to try and use schools as an arena to settle societal disputes, Ingersoll argued. “Usually, it's a story of asking the schools to do more and more and more, and not lengthening the day, not lengthening the year and on more and more topics,” Ingersoll said. “‘We have this societal problem, boom, let’s have the schools fix it.’”

For Yvonne, the veteran elementary teacher in Illinois, the increased contempt for teachers has been one of the most pronounced shifts she’s noticed over her long career. Parents have become “quick to attack,” instantly defensive and accusatory when a teacher calls home. Some parents air their grievances about individual teachers publicly on Facebook. The breakdown in trust saddens her, but she’s concluded that people now channel their rage toward teachers the same way they do to service workers. “It has nothing to do with us,” she said. “You know how people are mean to retail people, like you’re in Target and people are mean? It really has nothing to do with the Target workers. They’re just mad about something.”

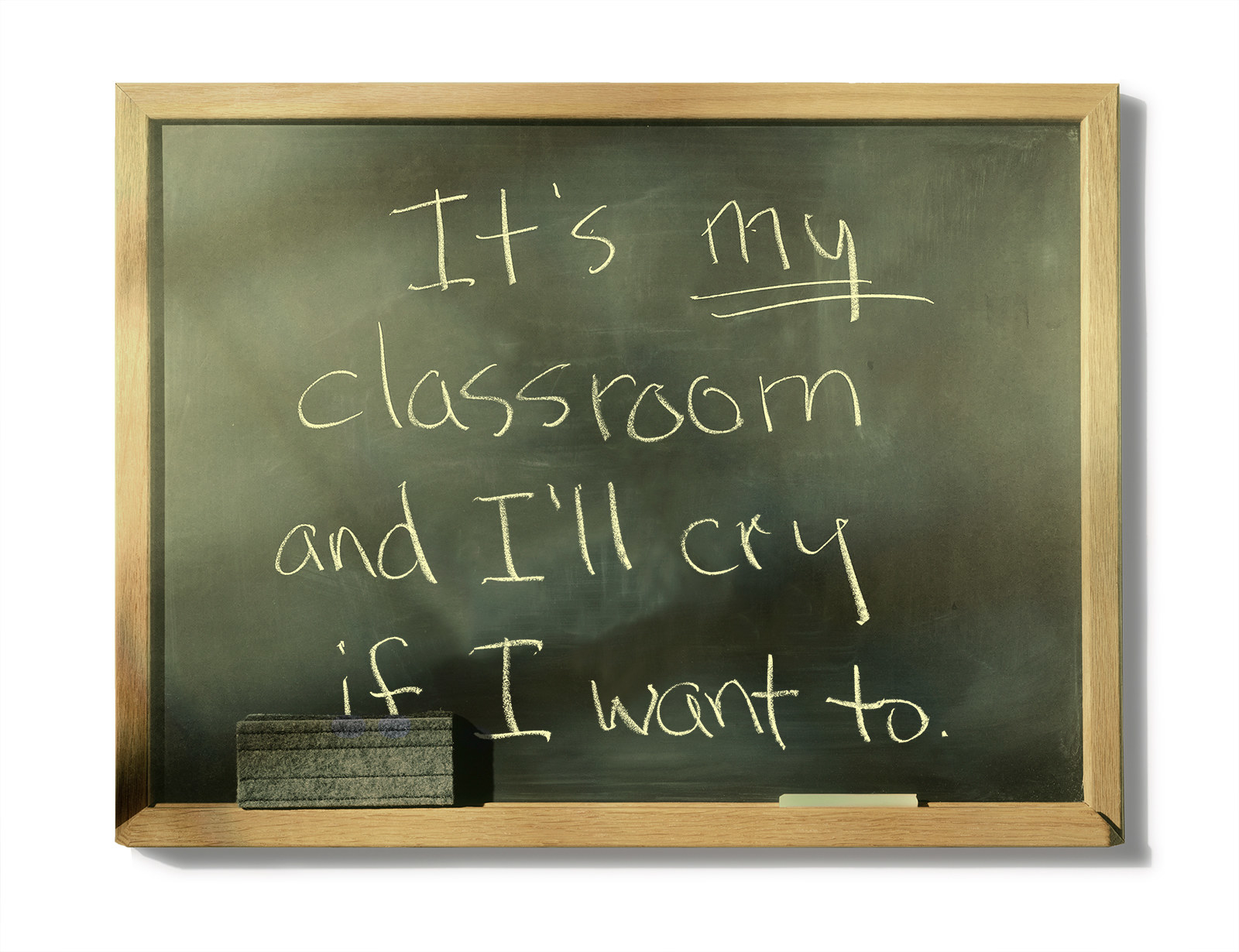

Left with no comprehensive way to staunch the flow of quitting teachers, the system has leaned on nominal stopgaps aimed at helping teachers cope. These may include professional development sessions focused on mental health and self-care, or regular school-wide appreciation emails. A teacher friend of Joe, the high school teacher in upstate New York, recently received a self-care kit from their school’s administration that came with a sheet of “reminders” printed out in colorful type on a sheet of paper. The advice includes affirmations like “I deserve to take care of myself” and “I am important & good at what I do.” Joe sent me a photo of it.

“It’s my classroom & I can cry if I want to,” reads one of these reminders. “Teaching is rewarding, but hard work. It’s okay to cry in a bathroom stall.”

“They also need reasonable hours, reasonable class sizes, and supplies.”

“I don’t think you could go anywhere besides an Amazon warehouse and see a sign that says you can cry in the bathroom, it’s OK,” Joe said. “For $56,000.”

The material realities prevent teachers from getting the kind of reprieve that could help keep more of them in the profession or at least improve their morale, even when administrators try to help. Donald P., the vice principal in Arizona, gives his teachers mental health days off whenever he can. “But I don’t have the staffing where I can give it as much as I want to,” he said. “And when my higher ups hear that I’m letting a teacher take a mental health day, I get my ass chewed out for it.”

All his teachers deserve a raise, Donald said, but that won’t alleviate all the problems with the job. “They also need reasonable hours, reasonable class sizes, and supplies,” he said.

Tierraney Richardson taught for eight years in elementary and middle schools before becoming an assistant principal in Texas. Though she’s still working in a school, she interviews teachers who mostly are not for her podcast, Teachers Who Quit. While increasing teacher pay would be a welcome change, “I think my pay could have been upped a lot, and I still wouldn't have stayed in the work,” she said. “And I think a lot of people do that. Because we're not driven by money. We already know going in that we're paid pennies, OK? We're doing it because of the purpose behind the work.” Giving teachers more support and decision-making power, Richardson said, would do more to keep them in the job; she herself left teaching for administration to try and fix the kinds of problems in school culture and leadership she had encountered.

“I love when I have those days where I’m like, ‘Oh my gosh, that was so much fun. I love my students, we did so much.’”

Support and autonomy are also measures that don’t have to cost anything, unlike politically unpopular raises. “Sometimes when I'm talking to legislators, I’ve had cases where a legislator will just stop me right in the beginning and say, ‘Look, Professor Ingersoll, give us some concrete things to do. But please, please, don't bring up raising salaries,’” Ingersoll said.

Many of the teachers leaving classrooms find jobs at educational technology companies or writing curriculum, which McNally, the former Atlanta teacher, now does. Teaching can translate to roles at tutoring companies and in training programs for businesses. At these kinds of jobs, they can escape the pressure and low pay and finally attain work-life balance. Teaching is a job too, but it’s also a craft, and for many people, a passion; and it’s bittersweet for some to think of a life without it.

Jasmihn Williams, a sixth-grade teacher in Salt Lake City, often sees advice online from former teachers on how to pivot to jobs she sees as much less fulfilling than teaching can be. “They end up in these like, tech jobs, which is fine, but it’s not really what I want to do,” Williams said. “I love teaching. I love when I have those days where I’m like, ‘Oh my gosh, that was so much fun. I love my students, we did so much.’ Those days are so worth it for me that I don’t really want to try something else right now.

“I would rather see through the other side,” she said of this moment in teaching. “But it feels like there’s never gonna be another side.” ●