When Lucas McNelly first began raising money for his film projects on Kickstarter in June of 2010, the crowdfunding giant was barely a year old. "I had to spend a lot of time explaining to people what they hell we were doing," he said, "Literally, half your time was explaining what it is, how Amazon is involved, hammering home the 'all of nothing.'"

"That is less important now," he says, deadpan.

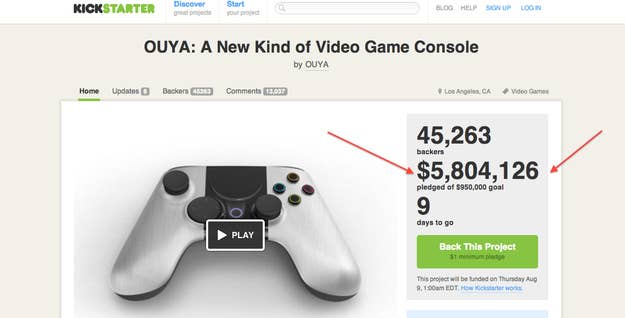

Now that Kickstarter funds more art than the NEA, it's a bit better known. In fact, Kickstarter (and lesser crowdfunders like IndieGoGo) have become the default funding mode for people who want to open restaurants, make video games, publish books, record albums and so much more. The platform is so ubiquitous it's now the subject of satiric pranks on its own website.

And it's spawned a whole new subeconomy — the professional Kickstarter(er)s, who get paid to manage campaigns and provide data to would-be entrepreneurs. So far, it's a small field but as crowdfunding grows — one estimate has Kickstarter raising over $120 million over the last year, with new multi-million dollar projects every month now, it seems — the people looking to raise money will increasingly need to bring polished, well-thought out projects to the marketplace.

The internet is teeming with blogs and web sites that dispense advice for free (and e-books have already been written) but McNelly is one person who charges for his goods. He's not alone, either. Victoria Wescott, a Canadian filmmaker, has also made a successful side hustle out of Kickstarter consulting, as has Los Angeles-based Josh Polon, who brags on his website that he has six campaigns for over $300,000 in the works this summer. (Thus far, Polon, who collaborates with a Duplass brother, has raised over $70,000 for his own film projects.)

And then there are the web video makers, who don't consult on Kickstarter per se, but who make professional videos for others' crowdfunding campaigns. Oakland-based Richard Parks co-founded a web video production company this past spring called Societeche. Also a filmmaker, he had successfully raised money for his documentary on Kickstarter, but wasn't expecting to make crowdfunding videos part of his business.

"No, we didn't think we'd be doing Kickstarter videos. We thought we were going to produce web commercials for companies that already existed, that were established," he said, "I think [we get Kickstarter queries] because we did a video that got some recognition in Silicon Valley, in the tech community." Thus far, he said, he's "been approached by a couple of dozen people, for wildly varying sums." One recent project, he noted, went into five figures.

Each consultant structures their services and fees differently. McNelly, who began charging to consult this past March, is particularly elaborate in his offerings. After a few successful campaigns on his own behalf, he said that he began writing blog posts about his insights into what works. And from there, "by default," he started taking on paying clients.

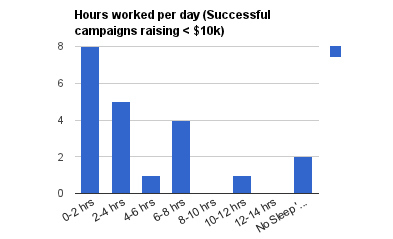

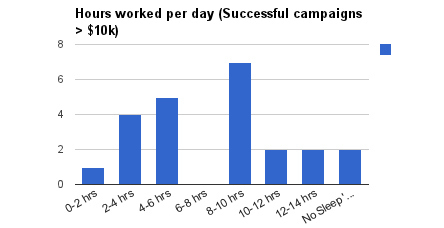

He offers three tiers of service. The least expensive is basic data: he has collected information on a number of crowdfunding efforts that could help inform one's choices on, say, how much to set as a target or what kind of perks to offer. This will cost you .75% of your goal.

Then there what McNelly calls "the setup" — helping figure out what the perks should be, how to shoot the all-important promotional video, etc. That is 5% of whatever gets raised.

And then there's the full-scale campaign management. "You can't just walk away and come back 30 days later," McNelly warns on his site, but for 13% of the total haul, he'll hold your hand.

In total, McNelly has gotten upwards of three dozen requests to manage campaigns and rejects about half. He is booked through September and is currently running this project for a man who's trying to make a movie before he goes blind.

It might seem odd that a platform like Kickstarter — launched to help underfunded artists find an audience — suddenly needs a class of people who make money off of consulting. McNelly said that he has caught flack for his new gig, but "that lacks an understanding" of Kickstarter's process. "It's like hiring a DP to shoot your movie if you're a director," he said. "Besides, you need three-to-four people to do a successful campaign. You're going to need help anyways." He says his success rate is over 90%.

As Kickstarter grows, it seems inevitable that more and more amateur Kickstarter experts will go pro. McNelly, logically, won't take clients who he doesn't think have a prayer of meeting their goals. To weed out the unrealistic, McNelly sends out a questionnaire before taking a client — "if they have 300 followers and say, 'I want to raise $50,000,' how is that going to work?" He also screens clients for their level of preparedness, recently rejecting someone who emailed on a Friday to start a campaign the following Monday.

All of this, he said, underlines the fact that crowdfunding is a serious business that has already deeply impacted the independent film community. As studios focus on popping out sequels of movies inspired by comic books, enterprising filmmakers have latched onto Kickstarter in a big way. And unlike the film festival circuit, the gatekeepers (in this case, Kickstarter itself, which vets projects) do not have any need to impose limits on how many projects can try to find audiences and funding.

"I don't think we've seen how big it can get yet. I think someone will have a million dollar film by the end of the year," he said.

As for the clients, McNelly points out that he works hard for them because, like an agent, he only gets paid if they do. So he's gotten lots of public praise like this tweet — from a group whose campaign failed, no less. Another customer, Damian Dydyn, whose May campaign successfully netted over $8,000, gave McNelly five percent of his proceeds for a customized data pack, a consultation and other support. "Lucas helped us to pick our perks, what days were best to start and end our campaign, and how long to run the campaign based on the data he had been collecting for quite some time from campaigns across the spectrum," Dydyn wrote in an e-mail, "Personally, I think his services are well worth the cost. I have no idea if we would have made our goal without him. It's an incredibly useful resource, especially for a first timer on Kickstarter."

"Anyone without a built in audience would be an idiot not to take advantage of this," noted another client, Jack Marchetti, whose campaign is currently in progress.

Parks said that he has been offered a percentage of Kickstarter spoils but prefers to work with a flat fee. Thus far, no complaints on their video work.

"In general, people are looking for a professional film look that's produced —probably something that someone who is asking for money shouldn't be able to get but now that's the norm," Parks said, "That's why people are starting to pay us our full rate to make a Kickstarter video."

Kickstarter itself doesn't appear to have anticipated the sub-economy their platform has created, as it was initially thought of as a way for the unprofessional to have access to global audiences. (Kickstarter did not respond to a request for comment.) As Kickstarter's co-founder Perry Chen told the New York Times in 2009:

“Money has always been a huge barrier to creativity,” Mr. Chen said. “We all have a lot of ideas we’d like to see get off the ground, but unless you have a rich uncle, you aren’t always able to embrace those random ideas.”

And this irony isn't lost on those profiting from Kickstarter: Parks, in particular, seemed a little befuddled that people would pay his company so much money on the crowdfunded platform. For McNelly, he said that he has faith that "it'll be a rising-tide-lifts-all-boats-situation," that the glut of Kickstarter projects means that more will be funded, in increasing amounts. Besides, the publicity alone can make even a ham-fisted crowdfunded concept worth the effort of running a campaign. "Maybe you don't hit your goal," he said. "But you get one or two people who get your idea."

Update: Corrected the founding date of Kickstarter — it was 2009, not 2008.