Disruption. It's really in the eye of the beholder, isn't it? Take a few high-profile startups that are part of the much-touted "share economy" — ride-sharing services Lyft and Uber. It turns out that where you stand on ride-sharing quickly becomes about larger values, like the role of government in regulating commerce. Start-ups, lean and often libertarian, lionize those who "think different." But governments have to be responsible to everyone, not just investors or shareholders.

Some people swear by these services, especially in cities like San Francisco, where taxis can be very, very hard to come by.

But to others, these newbies are a tarted-up menace to existing industy. “They’re hustlers,” a veteran cab driver told The Bay Citizen last month. "They’re not paying anybody any benefits, but they’re going out of their way to have no responsibility whatsoever.” Taxi companies are highly regulated, included having to abide by onerous insurance and medallion policies — which ride-sharing start-ups have managed to avoid.

At the heart of this dispute is differing notions of what's truly new about services like Uber, Lyft, SideCar, GetAround and more. Each of these ride-sharing apps have unique features — Uber leverages existing livery and taxi cabs by letting users book the car through their app, while Lyft and SideCar let drivers drive their own cars to pick people up, but skirt taxi rules by being "donation-based." Even though, in practice, these businesses do basically the same thing as a yellow cab: give people rides in exchange for money.

This week, the California Public Utilities Commission sent cease-and-desist orders to Lyft and SideCar, a similar service. It sent the same order to Uber two years ago, showing the commission's confusion over how to best enforce its rulings. In New York City, the taxi commission rejected Uber's bid to operate in the city, forcing Uber to offer rides for free — and Uber still can't operate in the city. Chicago saw even more aggressive action: a group of cab and limo companies sued Uber, claiming that their gratuity system was deceptive. Furthermore, the complaint charges that Uber confuses users by letting them book directly with the cab drivers, making it seem like Uber has an affiliation with the cab company (for insurance, say) when none exists.

"All the cities are different, have different laws, different jurisdictions, different relationships," Travis Kalanick, CEO of Uber, told me. "But the motivation is the same. The folks in the existing, incumbent industry [are] trying to slow down or stop the innovation."

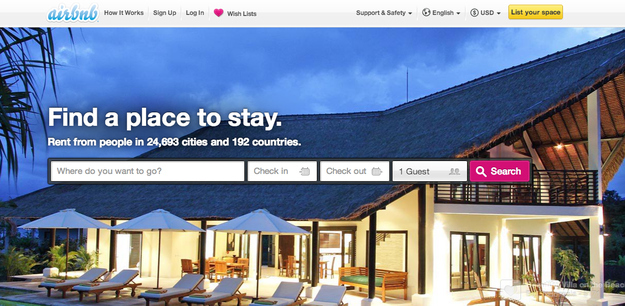

And ride-sharing isn't the only kind of disruptive start-up notion that is ruffling civic feathers: In San Francisco, Airbnb has been in a public fight with the city over the city treasurer's decision to levy a hotel tax of 14 percent on the service. (Tech-friendly San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee has formed a working group to discuss this, but for now, the tax stands.) Similar conflicts are taking place in New York City, where a 2011 law prohibits people from renting out whole apartments without being taxed (or regulated for things like fire code) — a common practice on Airbnb.

Of course, these sharing — or "peer marketplace" businesses — are disruptive and disruptive things tend to, you know, disrupt. "I could probably employ an entire army of lawyers researching every local issue out there," wrote Eric Koester, a founder of Zaarly, a company that matches skills to workers, answering a question on Quora about legal challenges to peer-driven start-ups. John Zimmer, the founder of Zimride (a long-distance ride-sharing service) and Lyft (its short-distance sibling, currently only operational in San Francisco), echoed this, saying, "Any new thing that we do has legal ramifications. We are deliberate and thoughtful with how we looking at city and more importantly, state regulations."

Kalanick, at Uber, said that when the California Public Utilities Commission sent a cease-and-desist two years ago, it came as a surprise: Uber thought, and continues to think, that its service is legal. He did make distinctions between Uber and newer ride-sharing services, like Lyft, in terms of regulatory complaints. "The difference between us and some of these other guys is that they have no commercial insurance to carry people — no carrier insurance. They don't have any licenses from the state," he explained. "Providing transportation without a license is a really serious problem." Uber works with livery and cab drivers, not ordinary citizens, so it doesn't risk having cars impounded.

As the ride-sharing start-ups expand, they're fighting on more fronts. Uber, the most established, got one of its first cease-and-desist orders from the San Francisco cab commission back in 2010. Uber ignored the order and the commission didn't take any further action. Since then, it's also run into trouble in Washington, DC — where a measure almost passed by the city council would have banned it outright — and in Cambridge, MA, where the issue was Uber's use of GPS technology. Just this week, Uber experienced a new problem: New York City taxi commission declared that a new app, aimed at flagging and paying for a yellow cab ride, was invalid for a number of reasons. The biggie is that Uber directly conflicts with one of the cardinal rules for yellow cabs in NYC: A cabbie must take a fare if he or she sees it, without discrimination — and Uber's policy is that the cab must travel to its pre-arranged fare. (Such apps like TaxiMagic have existed in other places for years but New York is still a place where you hail a cab outside.)

As a Bronx councilman told the New York Times, he was concerned about the possibility that these apps create “two-tiered taxi system," one for those “with fancy smartphones” and one for those without.

Kalanick defended Uber, reiterating his belief that its service is legal, noting that in "every city we've rolled out, we've continued to operate in," including NYC — although currently Uber only works with black sedan-style livery drivers. In terms of Uber's ongoing Chicago lawsuit, Kalanick denied that Uber was pocketing tips from drivers. "The business model in Chicago is similar to a hair salon, where the stylist pays a fee to rent a chair," he said. "That does not mean the hair salon is stealing the tip."

It sounds simple to resolve, almost, but the issues are deceptively complex. Take Lyft, for example. The idea behind this service, with the friendly pink mustaches, is to replicate experience of your friend giving you a ride — Zimmer said that he had heard of people going out for dinner at the end of a Lyft or staying in touch. Riders are encouraged to sit in the front seat, not the back. When I asked him how Lyft differed from a cab, besides the "different feel," Zimmer offered details on the method of procurement and payment. "It integrates technology. With a tap of a button, your friend with a car appears on demand. Technology makes that possible: requesting a ride, reimbursing from that ride."

But that doesn't differentiate Lyft, really, from a spiffed-up taxi. And taxi regulation goes beyond medallions that say who can and can't drive a cab. Take insurance, for example. In response to a report from The Bay Citizen that quoted personal injury lawyers saying that it was "troubling" that Lyft and Sidecar drivers were not carrying nearly the $1 million of coverage required for taxis, Lyft added that protection for drivers. It's similar to a move Airbnb was forced to make last year after the highly publicized vandalism of a house spurred the company to up its coverage to up to $1 million.

It's hard to say how much impact regulatory issues will have on startups, said Nick Economides (really his name), a visiting professor at Berkeley's Haas School of Business. "In the sense that this is a new business, they are having to negotiate how it's going to be regulated," Economides said of ride-sharing start-ups. "That seems very normal and straightforward."

A more dicey question is what exactly is new about "collaborative consumption" companies — and if the basic service is not new, why it should fall outside of existing rules? So far, these companies have survived, even flourished, all while clashing with local and state laws. And with cities like San Francisco eager to please tech companies, it seems plausible that some rules might be changed to accommodate the disruption that comes from the new businesses. Kalanick said that Uber would be looking to increase the list of 18 cities they currently operate in before the end of the year: "We feel like we're doing good business, creating new jobs, making the city more liveable."

But these controversies do take some of the air out of the hype around so-called collaborative consumption. "It could be that businesses think if they are put under this general rubric, they might escape regulation. The businesses can say, 'we are something completely different,'" Economides said. Even if they aren't.