A few weeks ago, Larry Ellison bought the Hawaiian island of Lanai, reportedly disappointing local residents who were hoping that the more magnanimous Bill Gates would sign the papers. He hasn't said what he's going to do with the island, but among a certain Silicon Valley crowd, buying your own island — or establishing your own country — has become as routine as snatching up your username whenever a hot new startup launches.

Take, for example, the "most successful technology investor in the world," Peter Thiel, who in 2008 announced the creation of a nonprofit called the Seasteading Institute, which is meant to "set the stage in order to empower" people and corporations to build and launch floating cities that will not be beholden to local governments. More recently, a few Thiel disciples debuted the Blueseed Project: a plan to put a giant boat outside of the San Francisco Bay. Although not quite a floating city, Blueseed would (theoretically) let startups evade immigration laws to work with talented foreigners.

Or if you're in the market, you could buy James Island, which is currently owned by telecom executive Craig McCaw — founder of McCaw Cellular, which he sold to AT&T, and more recently Clearwire — though he's now looking to unload it for $75 million.

Thiel, though, would be well-served by studying the long line of failed attempts by former captains of industry to create their own countries. It's an eternal desire: to be literally above the law. Here are some of the more notable attempts at nation-building on the micro level.

The Territory of Poyais

Gregor MacGregor, a Scottish adventurer, founded the Territory of Poyais in 1821. He claimed that his Honduran island was filled with fertile land and free of disease — all he needed were a few good British settlers. After collecting fees from over 200, the group sailed to "Poyais," where they found only some confused locals and raw jungle lands. MacGregor then took his story to France, where the con was shut down after the French government noticed visas being issued to an imaginary country.

Stated purpose: To provide virgin, fruitful land to Europeans eager to experience the Americas. Unstated purpose: to make MacGregor a lot of money.

Economic activity: Nonexistent.

Current state: Part of Honduras.

Lessons for tech billionaires: Stay vigilant against scam artists. You're a dreamer, so you're a mark.

View this video on YouTube

Video on Outer Baldonia

Principality of Outer Baldonia

Way before the Jose Cuervo brand established the "Republic of Cuervo Gold" (true story: I accidentally went there on a family boating trip and it was devoid of parties or people), a Pepsi president tried to establish an island nation near Canada. Russel Arundel founded the Principality of Outer Baldonia on a small piece of rock near Nova Scotia in 1948.

Purpose: According to a 1967 article in Sports Illustrated, Arundel found the island while fishing for tuna: Its "citizens" were all fisherman.

Economic activity: Stamps were once printed but mostly it was a spot for sports fishing.

Current state: In 1970, the Nova Scotia Bird Society purchased the island for $1 — a loss for Arundel, who paid $750 for it.

Lesson for tech billionaires: Control expenses if you are self-financing the nation-state. You cannot count on your citizens to pick up the tab.

Seborga

The oldest municipality in Europe, according to its residents, is the Italian town of Seborga. The hamlet declared itself a sovereign nation in 1963 and the head of a flower-grower collective proclaimed himself "His Tremendousness Giorgio I" (real name: Giorgio Carbone).

Stated purpose: To recognize the town's history. Giorgio claimed that when Italy was united in 1861, Seborga was not listed as a state. Therefore, they are not technically part of Italy.

Economic activity: Seborga has its own currency, the luigino, as well as their own stamps and a flag consisting of a white cross on a blue background. The population is small (a 2006 story pegged it as 362) so there's not much in the way of industry.

Current state: Before Giorgio died in 2009, a woman calling herself "Princess Yasmine von Hohenstaufen Anjou Plantagenet" asserted her right to the "throne" and tried to reunite Seborga with Italy. She communicated via a series of faxes, leading Giorgio to dismiss her as "the internet princess." At any rate, there is a new man on the throne: a 30-something textile heir who promises to keep fighting for Seborga's independence.

Lesson for tech billionaires: Plan succession carefully. If Giorgio hadn't successfully fended off the Internet Princess, Seborga might have quietly acquiesced to Italy.

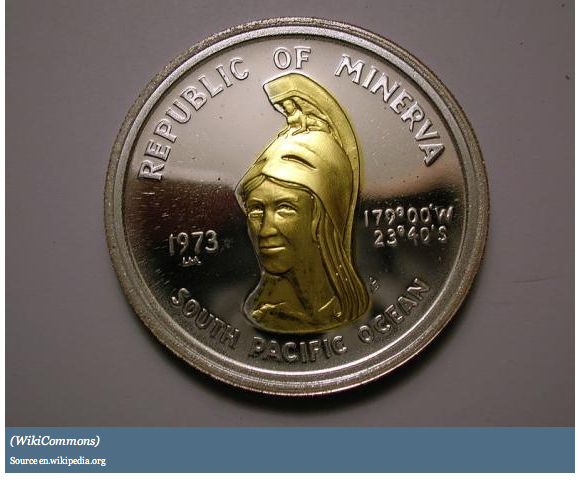

Republic of Minerva

Before the most infamous nation-founder is a man named Michael Oliver, a Nevada businessman and Holocaust survivor whose determination to have his own republic (lacking taxation, welfare or any other trappings of economic governance) spanned two oceans. In 1971, Oliver vowed to reclaim land for what he called the Republic of Minerva: He sent sand to reefs in the South Pacific, not far from Tonga, and declared Minerva's founding in 1972. Most of the world ignored him, save Tonga, who dispensed boats to the island to destroy the nascent island colony. Oliver then tried his hand at making an Australian island a sovereign country. It also failed.

Purpose: Libertarian utopia.

Economic activity: Minerva wasn't around long enough to have actual industries but an impressive two-sided coin was printed.

Current state: Minerva now belongs to the ocean.

Lesson for tech billionaires: Make nice with the neighbors first.

Sealand

In the mid-1960s, two “pirate” radio operators somehow found out about a disarmed anti-aircraft tower seven miles off the British coast. By 1967, Sealand was born. It is perhaps the best model for both Seasteading and the Blueseed Project: because of uncertain maritime boundaries, Sealand has a history as a semi-recognized sovereign space.

Stated purpose: Sealand was "founded on the principle that any group of people dissatisfied with the oppressive laws and restrictions of existing nation states may declare independence in any place not claimed to be under the jurisdiction of another sovereign entity."

Economic activity: Like many nascent countries, Sealand made money by issuing passports and selling coins.

Current state: According to Cabinet magazine, Sealand is now a data haven, home to servers from parties who do not want to be subject to a specific country's laws.

Lesson for tech billionaires: Choose a spot wisely. Sealand has been saved by its gray status as a steel offshore installation. Also, it seems that while many early "kings" did not anticipate the advent of the internet, secure off-shore data storage seems like a growth industry.

Oceana/Oceania

The Ayn Rand-inspired concept of an island nation called Oceana has gone through a few different versions. As Cabinet details, disciples tried in 1969 to build a new nation, starting with its defense system. (They actually made plans to steal a nuclear missile.) In 1993, a plan to build a free-standing island in the Caribbean took shape.

Purpose: Like Thiel's Seasteading Institute, the Oceana/Oceania folks are interested in free enterprise with a very minimal government.

Economic activity: While Oceania's plans tended toward the grand (30,000 residents), there didn't seem to be much planning re: financing. This could explain Oceania's short life: founder Eric Klien pulled the plug in 1994.

Current state: Alas, the hexagon buildings never got beyond computer animation. But in the shards of Oceania rose Klien's next venture: the Lifeboat Foundation, dedicated to "encouraging scientific advancements while helping humanity survive existential risks and possible misuse of increasingly powerful technologies... as we move towards the Singularity."

Lesson for tech billionaires: As always, PIVOT.