Like many concert promoters, Sascha Guttfreund, 25, has a gift for managing egos. His job is catering to young rappers, mostly — J. Cole, Kendrick Lamar, Big Sean, Chance the Rapper; stars of the genre still hurtling toward a peak — but his schmooze mode doesn’t have an off switch. In mid-March, inside an uncharitably small black Kia on a warm Wednesday in Austin, Guttfreund, who is about 6'3" and built like a college linebacker, indulged a chatty Uber driver who happened to overhear what he does for a living. “What’s the deal with Iggy Azalea canceling her North American tour?” asked the driver, a self-described Slacker Radio junkie with Costanza-pattern baldness and a five-o’clock shadow. For reasons unknown, he used the exaggerated vocal inflections of a drive-time radio DJ. “Why is Lil Wayne suing Birdman for millions of dollars?” he asked later, as a follow-up.

Guttfreund parried both questions with admirable sincerity, offering up a number of reasonable and informed theories as if a better use for his time had never occurred to him. “You ask great fucking questions, bro,” he said with gusto. That’s another thing you learn quickly about Guttfreund. He calls everyone — even people he has just met — “bro” or “brother.” To interact with him is to be unwittingly adopted into an ever-extending family.

Guttfreund lives in Austin with his business partner (and, for the last three years, romantic one) Claire Bogle, also 25, with whom he owns a house near the city’s idyllic Barton Creek. Together, they own 100% of ScoreMore, a boutique promotions company that operates in markets across Texas and Louisiana. In the world of concert tours, promoters are like matchmakers, pairing artists of differing scales with suitable venues in a given market. A good promoter knows the ins and outs of her market better than an agent or manager parachuting in from out of town, and maintains smooth relationships with a variety of desirable venues. As touring has remained one of the few consistently growing sectors of the music industry in the 21st century, promoting has become a crucial and lucrative business. The world’s largest promotions company, Live Nation Entertainment, which creates tours for A-listers like U2, Madonna, and Lil Wayne, raked in $4.7 billion in concert revenue just last year.

If Live Nation is Chipotle, ScoreMore is like an over-performing taco truck. The six-year-old company, founded before either Guttfreund or Bogle could legally enter most clubs, now has seven full-time employees, plus dozens more street-level promoters on contract in each of the cities where it operates. It promotes about 150 shows per year, most in underserved markets at venues with capacities ranging from 100 all the way to 6,000 people, and takes an industry standard 15% cut of ticket sales, plus bar returns, after artist fees and expenses. Since it started in 2009, the company has also launched two festivals — JMBLYA in Dallas and New Braunfels, and Neon Desert in El Paso — and seen 22x revenue growth, bringing in just shy of eight figures last year. Its fast rise, based largely on super-serving markets that bigger companies have overlooked, has made it a paragon of the new decentralized music industry.

Those who have worked with ScoreMore say the keys to its success have been identifying promising talent at an early stage, and going above and beyond to keep its clients happy. It promoted some of J. Cole and Kendrick Lamar’s first shows in the South — before either artist had a record deal — and both have remained loyal to the company, even as they’ve gone from the mixtape circuit to the top of the Billboard 200. “Of all the promoters I deal with across the country,” one hip-hop agent told me, “no one has a better relationship with artists than Sascha and his team.”

Back in the black Kia, Guttfreund and Bogle are discussing a small clan of young women in halter tops and minuscule denim shorts walking along the sidewalk. Each wears an array of colorful plastic wristbands stacked from wrist to elbow as in a ring toss. It’s the middle of SXSW — Austin’s annual 10-day music, film, and interactive conference — and the city is overrun by variously credentialed music lovers and industry flacks hoping to rub shoulders with artists at lavish showcases that run day and night. “They’re trying to get chose,” Bogle concludes dryly.

The chatty driver is taking us to St. Elmo Soundstage on Austin’s south side, about five miles away from the central hub of downtown. Starting tomorrow, it will be the site of the Illmore, ScoreMore’s five-year-old SXSW party thrown in conjunction with the hip-hop blog IllRoots, on which both companies have staked their name. Among hip-hop fans in the know, the Illmore is often discussed in near-mythical terms — a hyper-exclusive after-hours pop-up soiree with a reputation for attracting the who’s who of the genre’s new vanguard. Not officially sanctioned by SXSW, the Illmore is like an underground postscript to the conference, usually stretching from 11 p.m to as late as 6 a.m. Performances at the parties, which are somewhat improvised, are always a strictly protected secret and never announced beforehand. Illmore alumni to date include many of the biggest names in hip-hop and dance music: Lil Wayne, Skrillex, A$AP Rocky, Kendrick Lamar, Steve Aoki, Lil Jon, Big Sean, Diplo, Macklemore, and Kid Cudi.

Since it started in 2011, the Illmore has grown from a passion project into ScoreMore’s most high-profile event of the calendar year — the calling card on which it telegraphs its ambitions and growing cachet. At SXSW, where the world’s biggest brands go to farcical lengths in pursuit of buzz, the Illmore is a genuine phenomenon. On the day before this year’s event, a record 22,000 people have RSVP’d online for a chance to gain entry (compare that to the total number of official registrants to SXSW Music this year: 30,000), with fewer than 1,000 slots available for each of three planned nights. When the official Illmore Twitter account announced guaranteed three-night access, +1, to the first person to get a tattoo of the party’s logo, multiple submissions beamed in within 90 minutes.

En Route to St. Elmo, Guttfreund and Bogle take a call with VFiles, the avant-garde New York fashion boutique and amorphous lifestyle collective, which is hoping to become one of the Illmore’s sponsors this year. A regal blonde in black Audrey Hepburn sunglasses, smoky eyeshadow, and white high-top Vans, Bogle seems more weary than enthused by the call. She leans her head out of the window and smokes compulsively from a vanilla marshmallow vape pen. It’s a cherished vice. Neither she nor Guttfreund drink or take drugs.

Major brands like Beats by Dre, Red Bull, and Bud Light — all jockeying to siphon street cred from a ready-made reservoir — have already signed on to help foot the bill for the Illmore, which, unlike a ScoreMore concert, is invite-only and generates no ticket sales or other revenue. With building costs, security, stage, lights, sound, porta-potties, and insurance, among a long list of other line items, the party costs hundreds of thousands of dollars to produce.

Guttfreund has a round, boyish face and permanent puffy bags under his eyes that give him the impression of a teenager who missed curfew by six hours. He’s a gleeful negotiator with the useful ability to make you feel like he has nothing but your best interests in mind, even when he’s shutting you down. On the call with VFiles, a representative for the company starts pressing for backstage access in order to film interviews with Illmore guests. Guttfreund’s response is gentle but relentless.

“I just wanna make it clear, Jake,” he says, using the rep’s first name. “The whole reason why the Illmore exists is for artists to get away from everything feeling like a media tent. We’re where they can go without having cameras in their face, so doing interviews and stuff would actually be the opposite of the vibe we’re looking to establish. We’ve gotta be strict when it comes to maintaining the integrity of the vibe.”

After a few moments, Jake seems to have gotten the message. “No, no need to apologize, bro,” Guttfreund tells him.

In 2007, Guttfreund was a freshman at the University of Texas with no particular ambitions in the music industry. He majored in communications and paid his tuition by selling ads in newspapers, or cable door-to-door, or working as a waiter in a ranch-themed steakhouse. He had a reputation around campus for throwing parties — a skill that mostly served to support his fondness for illicit substances, especially weed, and alcohol, with which he first became acquainted at 15. Hip-hop was a passion. “It was conducive to the lifestyle I was living,” he says now. And in 2008 he decided to try his hand at throwing shows, instead of parties, for which he could sell tickets to students like himself. One of the first was with Afroman, a one-hit wonder whose 2000 song “Because I Got High” has had an enduring appeal among stoners.

Bogle, a New Mexico native who grew up preferring Tupac to bows and barbies, came on board shortly after the Afroman show. At the time, she was taking music business classes at Austin Community College and met Guttfreund through his roommate. ScoreMore grew by recruiting an army of like-minded students who were as proficient at selling tickets on Facebook and Twitter as they were on the street.

A half white, half El Salvadorian son of filmmakers from L.A., Guttfreund found that he could gain the trust of his favorite developing rappers by leveling with them, rather than posturing. Instead of promising more money than other promoters, he promised a better experience, and an opportunity to take their music to new horizons. It helped that he was a true believer — an enthusiastic champion and ally — and Wiz Khalifa and Wale signed up with ScoreMore early on. “I never pretended to be something I’m not,” Guttfreund says. “I’m not a gangster or anything, just a kid who loves the culture.”

It wasn’t all smooth sailing. Even as the business was taking off, partying as an occupational hazard was taking a toll. At 20, Guttfreund’s drinking had begun to consume him, and in three separate incidents in February 2009 he was arrested on campus, woke up in a hospital, and came to in his apartment missing his two front teeth — with a gash in his jaw — and no memory of what had happened to him. After a few false starts, he got sober in October of that year. “I just couldn’t live my life that way anymore,” he says now. Bogle, whose father was an alcoholic, followed two years later. She was 22.

“I was really good at getting fucked up and I wasn’t happy,” she says. “I used drugs and alcohol to escape life, rather than enhance it. I didn’t like the person I was. So yes, going sober was a choice, but it was a choice I knew that I had to make. It was, Do you want to be happy? Or not?”

Turning down a desolate, tree-lined road off the highway, we finally arrive at St. Elmo, a sprawling, hangar-like compound with metal siding in an anonymous, grey-blue business park at the end of a long driveway. Compared to the bustle of downtown or the east side, the location is utterly remote — the kind of place where Walter White from Breaking Bad might set up a clandestine meth lab. Guttfreund, cell phone still on his ear, gives me the grand tour.

The first Illmore was in 2011 and took place at a modernist glass and concrete mansion in Rollingwood, a well-manicured sliver of Austin’s hilly west side. Guttfreund and Bogle teamed up with Mike Waxx, then an 18-year-old blogging prodigy who had launched IllRoots four years prior, to rent out the house as a sort of crash pad for their mutual industry friends visiting from L.A. and New York. The living room and backyard pool were converted into ad hoc performance areas, and Mac Miller, Big Sean, The Cool Kids, Khalifa, and Kid Cudi stopped by as both performers and guests. If SXSW had become a circus with brands and media herding artists at the crack of a whip, the Illmore was conceived as the opposite — an off-the-grid no-spin zone where performers and their publics could have organic interactions. “It’s where artists can be fans,” Guttfreund likes to say.

The inaugural Illmore was a smash — and then some. Several days of partying left the mansion nearly destroyed, resulting in $30,000 worth of damage that the undergraduate organizers struggled for months to repay. The dilemma has shaped their thinking ever since: how to arrange for the ingredients of any great party — spontaneity, atmosphere, and a lack of inhibition — in a way that’s sustainable rather than self-destructive?

Last year was the first time the Illmore didn’t take place at a house, descending instead on the Millennium Youth Entertainment Complex, a 55,000-square-foot events center with a bowling alley and a skating rink. The extra space solved the event’s ballooning capacity needs, but many complained that the magic of the old house parties — the all-important “vibe” factor — had been lost in the expansion. During his performance that year, A$AP Rocky felt compelled to raise the ghost of Illmores past, addressing the crowd to challenge the palpable sentiment that the party just “ain’t the same.”

Though he’s reluctant to admit it, Guttfreund knows that the pressure on this year’s Illmore is higher than it’s ever been. He can’t have a repeat of last year, which he acknowledges may have been too big and felt too much like a traditional concert. More than a party, the Illmore is a critical forum for fortifying relationships with existing clients, and a demo tape that helps drum up new ones. A flop would be an embarrassing and costly ding to his reputation. In the music industry, any misstep can turn today’s wunderkind into yesterday’s news.

St. Elmo has been divided into three interconnected warehouses for the Illmore 2015, with a combined capacity of 999: a large main room with an open bar and games (350 cap), a neighboring complimentary hookah lounge with a second bar (249 cap), and a performance area, typically used as a film set, that is being outfitted with a stage (300 cap). The goal this year is to turn the vibes to 11, and flashy amenities abound. Guttfreund leads me past a foosball table, a live Bud Light-branded art wall, two arcade-style basketball shoot-out games, a claw machine filled with Illmore and Beats merch, enough crates of vodka (complimentary of Tito’s brand) and Red Bull to keep the Jersey Shore flush for a long weekend, and a barber’s chair, sponsored by Jay Z’s D'ussé cognac, where guests will be offered free straight-razor shaves. It feels like being in a manchild version of My Super Sweet 16.

Just as my tour is ending, a black car pulls into the driveway carrying Coran Capshaw, the silver-haired founder and owner of Red Light Management — the world’s largest independent artist management company with clients including the Dave Matthews Band, Tiesto, and Enrique Iglesias. Capshaw, in addition to being the sixth most powerful person in the music industry, according to Billboard magazine, is a personal hero of both Guttfreund and Bogle, who take a 20-minute meeting with him to discuss possible investment opportunities in ScoreMore over by the foosball table. Capshaw holds equity in major festivals like Lollapalooza, Bonnaroo, and Austin City Limits, and ScoreMore is looking for a partner to help develop more of its own festivals in smaller, tertiary markets like San Antonio and Tucson. “Other people can do the main dishes — we’ll be the sides,” Bogle says.

As he's giving Capshaw his vision for the Illmore, I overhear Guttfreund self-consciously deploy words like “weird” and “crazy.” Capshaw, 56, assures the younger man that he’s seen weirder. “I’ve been around,” he says. “We’ll have to get dinner sometime and I’ll tell you some stories.”

It’s the kind of thing people say casually all the time and then never act on. But Guttfreund actually has reason to be optimistic about the meeting. Already this week, he’s been to dinner with another one of his heroes, Dallas Mavericks owner and serial entrepreneur Mark Cuban, for whom he’s writing a business proposal. “I’ve seen every episode of Shark Tank,” he gushes.

Guttfreund, whose phone buzzes approximately every three minutes, tells me that the number one question he had for Cuban was about how to achieve a work-life balance.

“I love what I do, but I want to be a person too,” he says. “Family is important to me, friends are important to me. If this all went away tomorrow, I want to be able to wake up comfortable in my skin.”

Cuban’s response? “Family always comes first.”

Inside a windowless production space that will double as a backstage greenroom for artists, I find Mike Waxx, his IllRoots partner Cliff Skighwalker, and a small band of ScoreMore employees in T-shirts and hoodies going over logistics for the party tomorrow. Waxx is the Illmore’s creative director and social media guru (it was he who tweeted the tattoo promo), and was once an in-house videographer for Kanye West. At 19, he co-directed the video for Big Sean’s 2011 single “Dance (A$$),” featuring a twerking Nicki Minaj, which currently has nearly 71 million views on YouTube.

I ask Waxx, whose messy brown hair, peach fuzz, and oversize Adidas basketball shorts make him look like a shaggier Justin Bieber or a young Harrison Ford, what his favorite memory of the Illmore is. He doesn’t think twice. It was year three, 2013, at Austin’s American Legion Charles Johnson House. Kendrick Lamar, then touring in support of his 2012 breakthrough Good Kid, m.A.A.d City, brought the house down — literally. Around 4 a.m., a standing-room-only crowd started going wild during “m.A.A.d. city,” taking their shirts off and jumping up and down, causing the floor to partially collapse. Skighwalker, who was on the floor directly beneath the performance, says he saw the roof go convex. Paint cracked and dust particles rained down from the ceiling. There are insane videos of the melee online.

“I really think that one’s going to go down in history,” Waxx says.

There’s an episode of Broad City in which Ilana Glazer and Abbi Jacobson spend a night zigzagging across New York in search of the perfect party. At the second of several stops, Jacobson protests Glazer’s insatiable lust for discovering “the Narnia of parties” — a 10 out of 10 on the proverbial rager scale.

“But I’m having fun,” Jacobson complains before being shuffled out the door of a pleasantly dim apartment.

“You think you are,” Glazer replies. “But this party is a 7. We could be missing out on a 10!”

Glazer’s concern, the fear of missing out, or “FOMO,” is both obviously irrational and profoundly human. Anyone who has ever attempted to plan a New Year’s night out, or lingered in first class while boarding an airplane, knows it well. The most desirable party is always the one you can’t get into.

As much as anything, the Illmore is a FOMO factory — a meticulously engineered black box designed to stoke awe and envy among the uncredentialed masses. ScoreMore employees tell extraordinary stories of party hopefuls rushing them in the street, or showing up to the gate with $1,000 in cash, hoping to bribe their way to a coveted wristband. The party’s organizers take some joy in fomenting the hype — the only official way for music industry outsiders to gain access is by picking up one of only a few dozen wristbands at a surprise location announced just hours before doors. Emerging triumphantly from one of these locations — often an unassuming parking lot outside of a strip club or restaurant — typically requires Hunger Games-level bloodthirst.

“If you’re supposed to get in, you’ll get in,” Waxx tells me of the Illmore’s admissions policy. “If you’re not supposed to get in, then you won’t.”

The elusive nature of the Illmore is a double-edged sword. Not promoting a lineup and choosing locations far from downtown has helped the party avoid the ire of SXSW’s owners, who have a history of using their connections with the city to crack down on unofficial parties that draw too much attention to themselves. But it also creates predictably unreasonable expectations. Those who make it inside the party’s hallowed walls come expecting to experience a 10 out of 10 — anything less is a disappointment.

On Thursday afternoon, less than 12 hours before doors open at 11 p.m., I find Guttfreund at St. Elmo chatting up a long-faced agent with the Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission. Wearing Air Jordans and head-to-toe black sweats emblazoned with the Illmore logo, he’s in full salesman mode, going into fine detail about the mission of the party.

“If you’re Wiz Khalifa, this is where you go to get away from SXSW and just hang out,” he says. “It’s invite only — no tickets. We’re not selling anything here.”

At the same time that this conversation is happening, the party’s producer, Gina Martinez of Splendid Sun Productions, is giving a tour to the fire marshal. She has curly black hair in a ponytail and a concerned look on her face. Some exit signs are too faded and will have to be replaced, and the stairs leading from an outdoor hangout area to the main bar and games room may not be up to code.

Along with ScoreMore, Splendid Sun produces Neon Desert, a hip-hop and electronic music festival in El Paso, and the two companies have grown close. Martinez, who is older than the average ScoreMore employee by maybe 10 years, is a stabilizing maternal presence — she calls Guttfreund and Bogle “mijo” and “mija.”

This is the first year that the Illmore has worked with an outside producer, and it was Martinez’s idea to go aboveboard with the city. In previous years, the parties have skated by under the radar without permits.

“This shit scares the shit out of me,” Guttfreund tells me after dispatching the TABC agent. Government scrutiny nears the top of the list of things that could derail the party before it starts. But adding to his nerves is the fact that he won’t be around to see how everything is resolved — in a few hours, he has to drive to San Antonio to be with J. Cole for a stop on a tour ScoreMore is promoting. He’ll return after the party is well underway.

I ask him if he got any sleep last night. “Not really,” he says. “The night before I only slept three hours.”

As it turns out, Guttfreund’s apprehensions about permitting are well-founded. Crisis strikes less than an hour after he decamps for San Antonio. ScoreMore’s lawyer, after speaking with the TABC agent, has a tense meeting with Bogle and Waxx in the greenroom. It’s carpeted and lamplit with a long sofa and a smattering of stray computer chairs. Boxes of Illmore wristbands of varying colors lay on the floor.

Because of a quirk in the zoning of St. Elmo, the location is considered a public place and cannot serve alcohol after 2 a.m., the legal cutoff in Austin, as has been done at previous Illmores. For an after-hours party, this is a devastating blow. Bogle looks as if she’s just watched a cab pull away with her wallet and cell phone inside.

“Our party doesn’t fucking START until 2!” she yells. It’s the only time I see her less than fully composed. Several more f-bombs follow. Bogle, Waxx, and the lawyer huddle to assess damages and debate strategy, like climbers who’ve just lost a foothold.

If there’s no alcohol, will anyone come? Maybe we can tell everyone to come early and just pour really strong drinks? Can the sponsors pull out? What will this do to our reputation? What will happen if we do it anyway? Can they arrest us?

The lawyer ends the conversation by promising to make some phone calls, but there are no easy workarounds. Perhaps there was a time when the Illmore could have claimed it was merely an innocent gathering of friends who didn’t know any better. But certainly that time is long past.

Later, after several rounds of vanilla marshmallow vape therapy (“This is for when I’m like, Don’t shoot yourself, Claire,” Bogle deadpans), the crew forges ahead as planned. Waxx distracts himself by designing step and repeats — the logo-printed backdrops used on red carpets — that will eventually cover the walls of the hookah lounge. A gang of his associates, whom I can’t decide whether to give a noogie or a job, mine YouTube for “the most fire Vine compilations” to project in the main room. It’s around 3:30 p.m. and representatives for tonight’s performers will soon be arriving to pick up credentials and check out the space.

Because it’s not a formal, ticketed concert, artists who perform at the Illmore aren’t under contract nor paid a fee. And since the lineup is kept fluid, many aren’t confirmed until hours or even minutes before going onstage. Guttfreund, Bogle, and Waxx must lean on their formidable connections to lock in talent with only a friendly handshake and the promise of good promo and good times.

Few promoters twice their age would dare approach an artist at the level of Lil Wayne or Skrillex — who regularly sell out stadiums — to play an unpaid, unannounced gig for a few hundred fans in a tiny DIY venue. But when it comes to the Illmore, many artists clamor for the privilege. This year, the biggest rapper in the world, Drake, was in talks to make his first appearance at the Illmore. But plans fell through after he received a conflicting invitation from the royal family of Dubai. Another superstar, Miley Cyrus, has been emailing about possibly coming with the super producer Mike Will Made It.

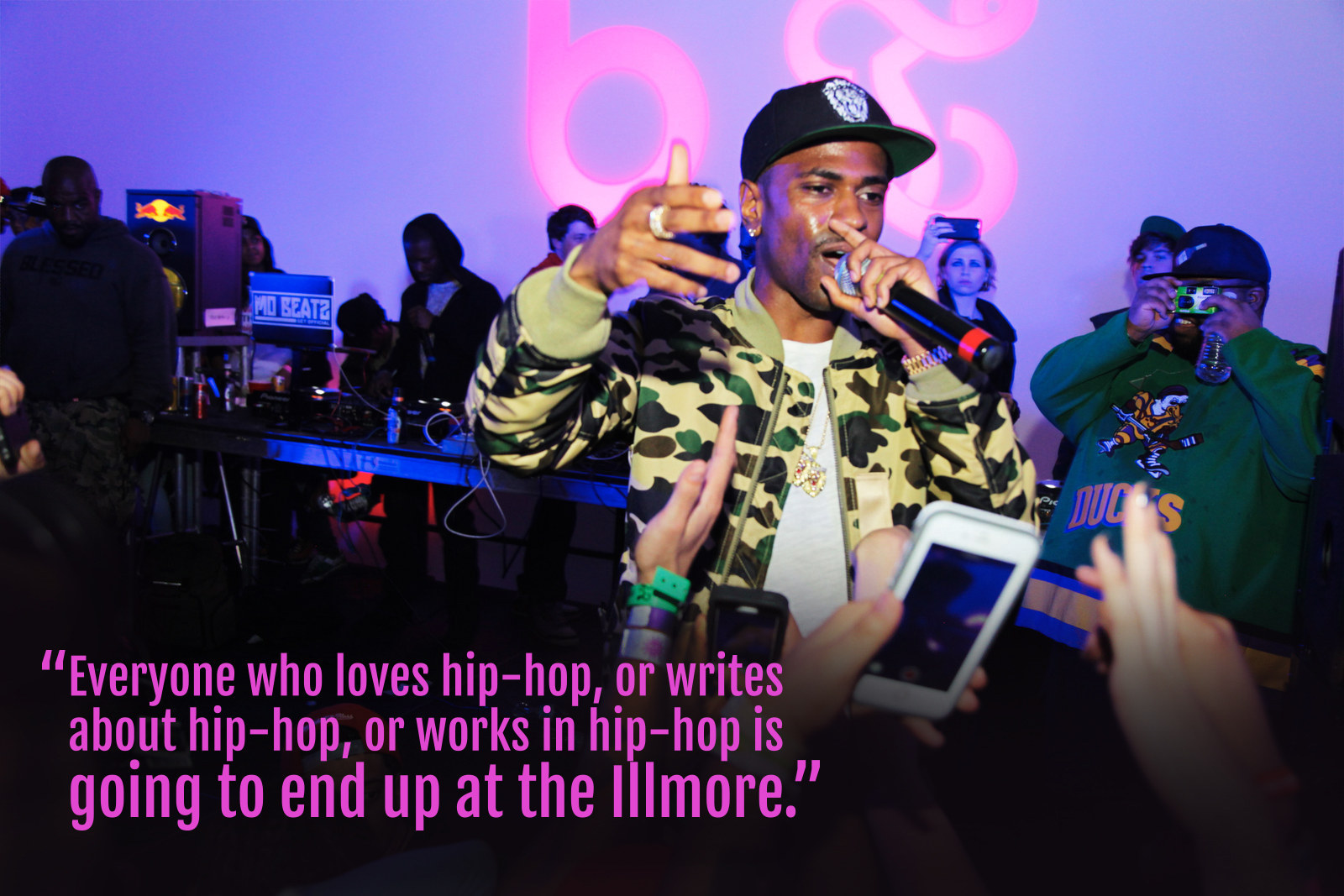

“It’s the hottest ticket in town,” says three-time Illmore veteran Jon Briks of the Agency Group, which represents acts like A$AP Ferg, Macklemore, and Muse. “During South By, it’s the place that everyone who loves hip-hop, or writes about hip-hop, or works in hip-hop is going to end up. It’s better exposure than doing a show in New York or L.A.”

Though no money may change hands, the Illmore tends to support artists who support it. Two years ago, a rapper in town for SXSW and scheduled to perform at the party got busted on a weed charge. In Texas only for a few days, he needed a get-out-of-jail-free card. Guttfreund and Bogle found a local lawyer who came to the rescue.

Right now, in the St. Elmo greenroom, Bogle is making a different sort of accommodation. Chance the Rapper’s tour manager, a skinny kid with a five-panel cap pushed back far on his head, has just arrived with an audacious request: 70 wristbands to distribute among Chance’s personal entourage. That’s enough to accommodate the starting lineups of 12 NBA teams. Avoiding Bogle’s gaze, he wears the half-guilty expression of a man who just ordered two entrees at dinner.

Seated on the couch with her hair pulled into a knot, Bogle reaches into a box of blue wristbands in front of her and pulls out a handful. “This is for whores, sluts, girls,” she says calmly, pressing them into the tour manager’s two open palms.

She reaches into another box and grabs a smaller handful of black wristbands. “This is for 10s — I’m talking super bad bitches.”

Then she reaches into a third box and fishes out an even smaller assortment of white wristbands. “This? This is for crew only,” she says. “No one should have these unless they need to be onstage.”

In total, the tour manager now holds 60 wristbands. He smiles and thanks Bogle with a little bow. “I know how you fuckers roll,” she says.

After spending two days preparing to party, reminiscing about other parties, and engaging people in discourse about the nature of parties, the time to party has finally arrived. It feels a little like prom night for the planning committee.

I arrive at St. Elmo slightly before doors open at 11 p.m. on Thursday. The scene is eerily quiet. Since I was here this afternoon, the entrance to the compound has been barricaded by a blacked-out fence, which is being tightly patrolled by several black-clad security guards. Hanging from the fence is a large white vinyl banner with “Illmore” printed in a gothic typeface.

To the left of the banner stands a 50-yard line of onlookers in snapbacks and hoodies, the “have-nots,” who are hoping to make their way inside the party despite ruefully naked wrists. To the right of the banner, at the end of the fence in the shadow of a streetlight, is a much shorter line of “haves” — wristband holders waiting in oddly silent anticipation. Perhaps they think the Illmore is like Fight Club, and by merely talking about being on the inside they could find themselves expunged. I work my way through the crowd and head through the gates.

Outside the Illmore’s trilogy of warehouse structures, white vinyl tents and tall standing tables draped in Mexican serapes create designated hangout areas with a tropical bohemian vibe. There are lawn chairs and little potted palm plants, with everything bathed in soft multicolor floodlights. Walking up from the long driveway at night, it looks like a neon oasis in a concrete desert.

Past the tents and up some stairs I enter the hangar-like main room, with the open bar and shoot-out basketball, made open-air thanks to a front-facing garage door. The Beats by Dre and Illmore logos are projected side by side in red along a white wall. Lil TerRio dances nearby on a loop. By now, people are starting to trickle in and soak up the vibes. I grab the first of too many Red Bull and vodkas and head for the basketball.

A funny thing kept happening on my first night at the Illmore: People kept telling me to wait for night two. Cliff Skighwalker, the IllRoots blogger, was already looking toward the future when I spotted him outside of the green room around 12:45 a.m. “Tonight’s more of like a trial run where we’re testing things out and seeing what works,” he said. “Tomorrow, though, that’s when I think things are gonna get really special.”

When I bumped into Waxx, he said basically the same thing, that tonight was more or less a soft opening, and that Friday and Saturday nights were the ones to watch out for. I wasn’t sure what to make of this. Over the past 48 hours, I’d watched these same people working tirelessly for the sole purpose of etching the coming three nights into the annals of party history. And now they were suggesting that one of those nights would essentially be a wash. Was it opening night jitters? Had a key performer canceled? Was a loophole to the 2 a.m. booze cutoff within tantalizing reach?

I looked around and saw no obvious reason why the night was failing to live up to expectations. Everywhere people were standing in clusters clutching little white plastic cups, giddy and over-caffeinated. I did notice that the foosball table wasn’t being used much, and that the barber and his chair often had no takers. In a sense, it was like any gathering of adults at a carnival — some played, most gawked.

In the performance area, where the white walls of the stage glowed purple, blue, and red under overhead lights, Hot 97’s Funkmaster Flex warmed up the crowd with an aggressive, if not necessarily inspired, special DJ set. Drake’s “10 Bands,” Big Sean’s “IDFWU,” Meek Mill’s “Dreams and Nightmares.” Around 2 a.m., the special guests started rolling out: Chance the Rapper, who announced himself as the evening’s host and resurfaced on a handful of occasions to play hypeman, Dej Loaf, Rome Fortune, Fetty Wap, and DJ A-Trak. It was a solid opening lineup — Loaf and Wap are among the year’s most promising and creative new talents — but devoid of true star power. The crowd often seemed to be waiting for a “holy shit” moment that never quite came.

And there were sound issues. The mic was muffled and mixed too low, a critique more than one audience member lobbed toward the stage to no avail. Additionally, many of the performers sang over the commercially recorded versions of their songs — vocals and all — giving the shows an unfortunate karaoke feeling. Guttfreund later told me this was a quirk of the unplanned nature of the performances — the artists simply didn’t have instrumental versions of the tracks on them.

But even if the performances had gone off without a hitch, the increasing sobriety of the crowd had a noticeable dampening effect on the evening. The bartenders stopped serving just as the first performers took the stage, and the energy level never quite reached a critical mass. “Have y’all ever been to a concert before?” Chance snapped at one point. By 3 a.m., a once-packed room of about 300 had dwindled to around half that. By 3:30, A-Trak was playing trap music to just a couple dozen people crowded around the stage.

Outside after the show, I bumped into a deflated-looking publicist with a red goatee and a gray backpack. He said he had been to several Illmores in the past, and I asked him how he thought this year was going. He thought for a minute, then gave me a four-word review: “More difficult, nicer couches.”

So, not exactly historic. But there were a lot of things still going in the Illmore’s favor. I called an Uber and prepared for round two.

Illmore Night One Rated in Terms of FOMO-Worthiness: 6.3/10.

One of the challenges of SXSW is the unceasing demand for surprises. Even compared to other music festivals, where witnessing a secret performance is a kind of badge of honor, the rumor mill at SXSW is on perpetual overdrive, with an apocryphal new celebrity sighting at a taco stand or Samsung hut reported on social media every three to six hours. The steady supply of rumors fuels an annual snipe hunt — everyone in town stands at the ready for a pop-up Kanye or Rihanna or Drake performance that, more times than not, never materializes. (Sometimes, of course, it does — à la Justin Timberlake at a MySpace Secret Show in 2013 — and the hunt is renewed.)

The constant expectation of surprises, the sense that an A-lister lies around every corner, makes the Illmore’s promise of an all-surprise lineup for three consecutive nights a complicated proposition. On the one hand, FOMO runs so high at SXSW that a vacant slot on any lineup does wonders for turnout. On the other hand, competition to secure artists for truly unexpected performances is increasingly fierce. Most of the higher-profile performers who take the stage at Illmore at 2 a.m. have already made much-ballyhooed appearances earlier in the day at showcases sponsored by The Fader magazine, or Pitchfork, or The Hype Machine.

On Friday night, I thought about this dilemma as Mike Will Made It was set to perform at the Illmore with special guests. The previous day, he had created a genuine Moment at the Fader Fort, a daytime party, by bringing out Miley Cyrus — a feat that I knew the Illmore’s organizers were hoping he’d repeat tonight. Also on Friday’s list of performers was Big Sean, who had made his own unannounced appearance at the Fader Fort just hours earlier.

The fact that the Illmore competes with the Fader Fort — widely regarded as the gold standard for SXSW parties — for top-level talent is a testament to the scale that its young organizers have been able to achieve in five years. But Guttfreund insists that his party isn’t trying to become the next Fader Fort — which, unlike the Illmore, is officially partnered with SXSW and promotes its lineup in advance — or step on anyone’s toes.

“We love [the Fader Fort], but it’s like comparing Shaq to Allen Iverson,” he says, with the Illmore presumably playing the point guard in that equation. “Our games are completely different.”

Despite rain, Friday at the Illmore was a marked improvement on Thursday in terms of vibes. The showers forced everyone indoors and created a welcome sense of intimacy. Additionally, the hookah lounge, which on Thursday had been reserved for VIPs, was made open to the public. It was an instant hit. Girls in angular jewelry and patterned leggings danced and smoked with boys in rare sneakers and expensive denim.

As for Miley, she never showed up; but the crowd didn’t know to miss her. Mike Will Made It brought out Atlanta hit-maker Future and the perpetually shirtless party rap duo Rae Sremmurd instead. They performed on thankfully improved microphones. When Big Sean took the stage in front of a capacity crowd, people genuinely lost it. I was reminded that the thrill of the best experiences erases the anxiety of their anticipation.

Illmore Night Two FOMO-Worthiness Rating: 8.1/10.

On Saturday afternoon, I called Guttfreund and asked him how he thought things were going. I wanted to know whether he regretted going to the city for permits, whether the Illmore had gotten too big, too mainstream, less fun. He didn’t see it that way: “We did what we had to do to ensure the safety of our guests.”

“I feel a thousand percent better about the Illmore 2015 than I did about Illmore 2014,” he went on, referring to the party at the Millennium Youth Complex. “This year we’ve got the vibe back, it feels very much like a party. It’s very DIY. And we’ve got festival-level artists performing in a tiny room for 300 people. Where else does that happen?”

Guttfreund and Waxx told me they’re looking to expand the Illmore parties to other locations beyond SXSW. They’re not sure where exactly, but Miami during Art Basel and Chicago during Lollapalooza are of interest. “Anywhere our colleagues go and are stressed out, we look to provide an alternative experience for them to enjoy themselves,” Guttfreund says. For ScoreMore, the goal over the next few years is to start promoting full tours with artists across the country and beyond, and — possibly with a partner like Capshaw or Cuban — to expand its festival offerings. Guttfreund and Bogle have also branched into artist management, representing the developing artists Tory Lanez and Kali Uchis, respectively.

Of the three, Saturday night was the Illmore’s most seamless. After the jitters of night one, and the rain of night two, everything and everyone seemed to be firing on all cylinders. It was the last night of the party, and the last night of SXSW at large, and the sense of shared triumph was palpable. Guests wore their wristbands a little more loosely. I even noticed the D'ussé barber, in a new location behind the claw machine, had as many takers as he could manage.

Performers on Saturday included OG Maco, Vince Staples, Trae tha Truth, Bun B, and J. Cole, the latter of whom was playing the Illmore for the first time. Cole, whose most recent Billboard No. 1 album, 2014 Forest Hills Drive, marked his full transition from underground favorite to mainstream force to be reckoned with, seemed a fitting choice to close out the Illmore. As he was wrapping up, I spotted A$AP Rocky and Zoë Kravitz nodding their heads by the stage. Neither artist had been scheduled to perform that night; they just came to hang out.

After the party was over, I caught up with Rudy Guerra, a 23-year-old San Antonio native who has been to every Illmore since 2013. This year, he had been standing in line at his local tattoo parlor when he saw the offer for guaranteed three-night entry on Twitter. The Illmore logo is his latest tattoo of seven, a curly script “I” on the inside of his right ankle.

“This year I had the time of my life, honestly,” he tells me, a little breathless. “The Illmore isn’t like other parties or concerts. You never know who you’re gonna see or what could happen.”

I ask him if he’d do it over again, if given the chance.

“Absolutely,” he says immediately. “I have no regrets whatsoever. It’s going to be an awesome story to tell one day.”

Illmore Night Three FOMO-Worthiness Rating: 9.0/10.