Last July, actress Emma Roberts posted an Instagram photo of herself posing with a canary yellow copy of Eve Babitz’s 1979 novel Sex and Rage. Roberts’ hair is tousled, her teal floral dress hiked up as she lolls on a chaise — the paperback slouched across her chest like an elegantly deflated tent. Now a preeminent influencer in the literary world, Roberts’ Instagram account often serves the purpose of promoting her book club, Belletrist, and the titles and indie bookstores it champions.

“As a young girl growing up in Los Angeles, I spent a lot of time and energy trying to figure out who I was,” reads Roberts’ caption. “I think this is true for young women growing up in most places — and it is for this reason that we choose Sex and Rage, by the legendary Eve Babitz, as our July Belletrist book pick. Babitz’s heroine, Jacaranda, speaks volumes to the messiness and mistakes that mark adolescence.”

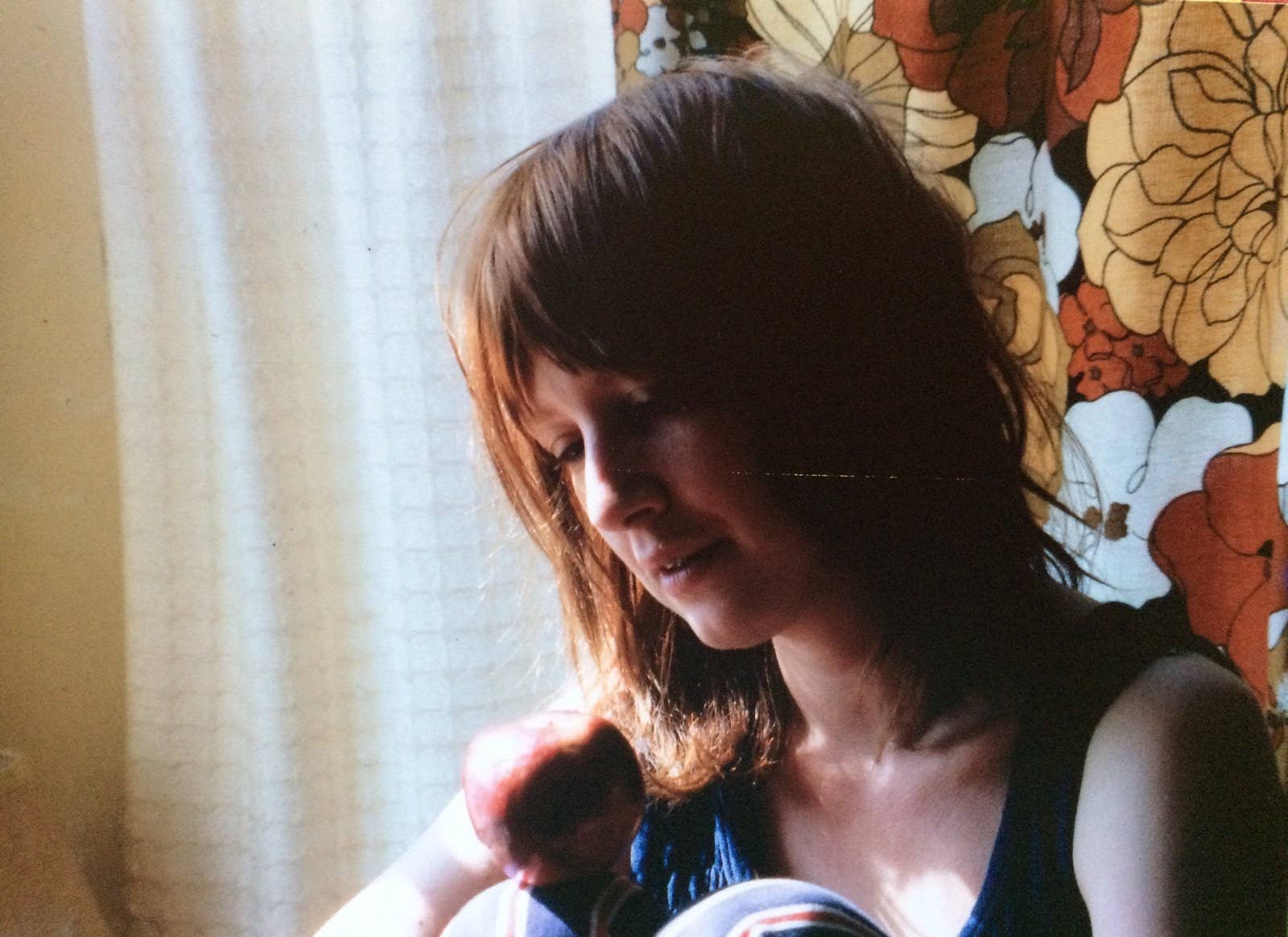

It’s an apt enough endorsement for the novel, but to refer to Babitz as “legendary” implies a ubiquity that, until recently, was more befitting of fellow California author and literary It girl Joan Didion. After an accident in 1997, Babitz receded from public life: She had suffered third-degree burns across the bottom half of her body when flecks of cigarette ash set her skirt aflame. The ordeal left her disinclined to write, take interviews, or, generally speaking, maintain her legacy as one of LA’s most illustrious women.

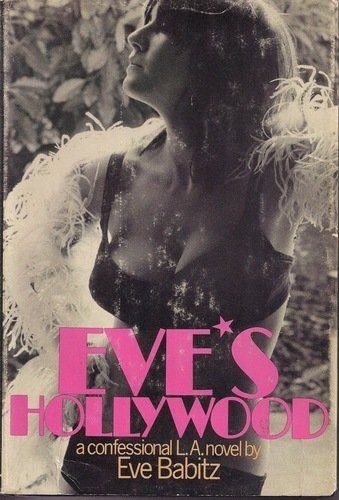

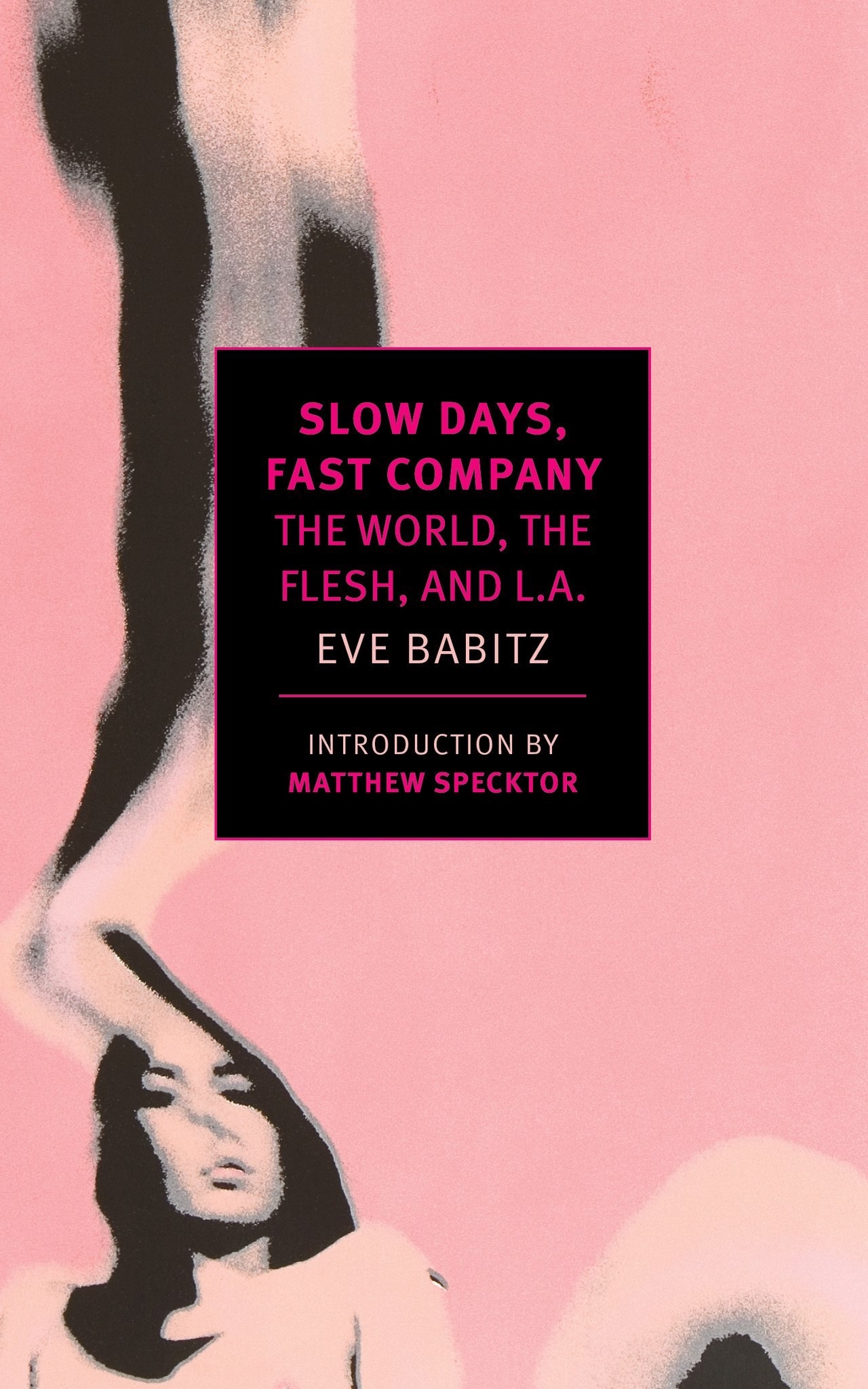

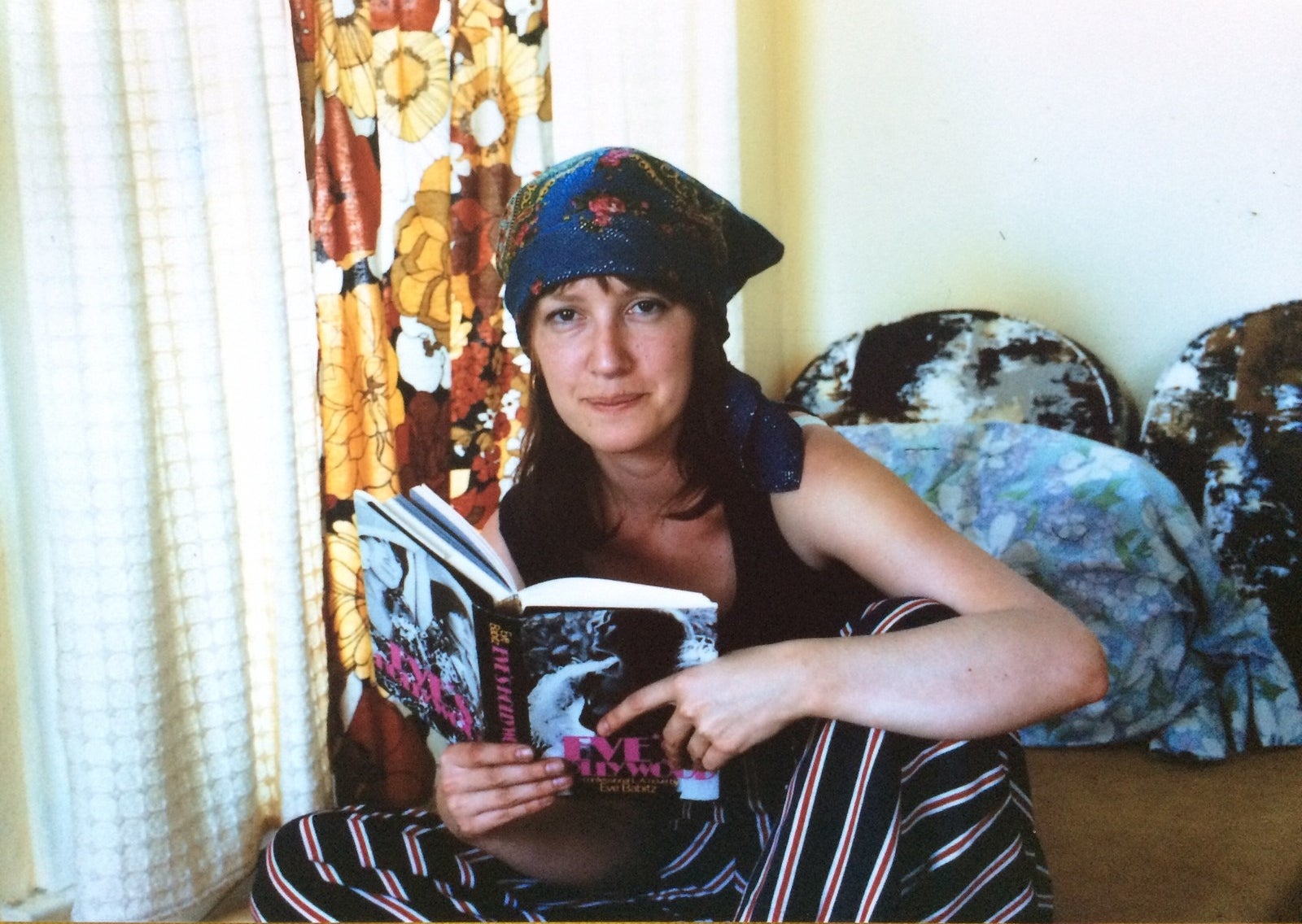

Her books long out of print, Babitz has for decades dwindled on the outskirts of cultural consciousness, until now. Her recent renaissance, like her writing, has been both propulsive and rapturous. In October 2015, New York Review Books reissued her roving, decadent memoir Eve’s Hollywood (originally published in 1972), followed by Slow Days, Fast Company (1974) in August 2016. Counterpoint Press took their turn in 2017, publishing their edition of Sex and Rage in July. In October of last year, Hulu announced that it was developing a comedy based on Babitz’s memoirs titled, after her novel by the same name, L.A. Woman.

Then, this April, Counterpoint Press released Black Swans (1993), a wistful collection of nine autobiographical tales from the 1980s and ’90s. By then, Babitz’s tidal pull — sumptuous prose organized into vignettes of hedonism without the weight of moral consequence — had lassoed the attention of bookish women, and, seemingly, everyone else too.

Babitz’s tidal pull — sumptuous prose organized into vignettes of hedonism without the weight of moral consequence — had lassoed the attention of bookish women, and, seemingly, everyone else too.

In celebration of the reissuing, the New York Public Library hosted a panel moderated by Girls star Zosia Mamet and composed of sharp, hip women from the literary world. One month later, LA Weekly marveled at Babitz’s millennial aesthetic appeal. Readers, particularly literary women in their twenties and thirties, seem to be entranced by this child of Hollywood, who unabashedly relished her LA milieu and both chronicled and defended its paradoxes. But it’s still a milieu that flattens the city into one that is homogenous, wealthy, and white.

What’s captivating about Babitz’s particular mode of confession is that it’s anchored by an intuition that renders her environs both so enchanted and familiar. And her irreverence in the face of persistent expectations of feminine decorum — reanimated like a sociocultural zombie during this administration — can cause a sigh of relief. She has always been, as she explains in Black Swans, a “shimmering charismatic,” and resultantly, a polestar for “fun” and devil-may-care delight, that she and her companions:

are such gluttons for narcissistic fantasies ... that we began our lives knowing that sinking into gracious old age, being happy about grandchildren, planning family dinners, being proud we put children through college or had children not in jail — these are not the things we meant by “life” when we started. I mean, they may have happened, but not on purpose.

It’s a breezy rebuff of heteronormative relationships, while also alluding to a seductive life of carefree sex influenced by her own life experiences. But it’s also saturated, as so much of Babitz’s writing is, with a carelessness afforded by whiteness and beauty. Her blithe acknowledgment of her own beauty’s benefits — “I looked like Brigitte Bardot,” she writes in Eve’s Hollywood — ignores the fact that this likeness would not be so advantageous if it did not signify the blonde, fair-skinned aesthetic venerated by the whole of the Western world.

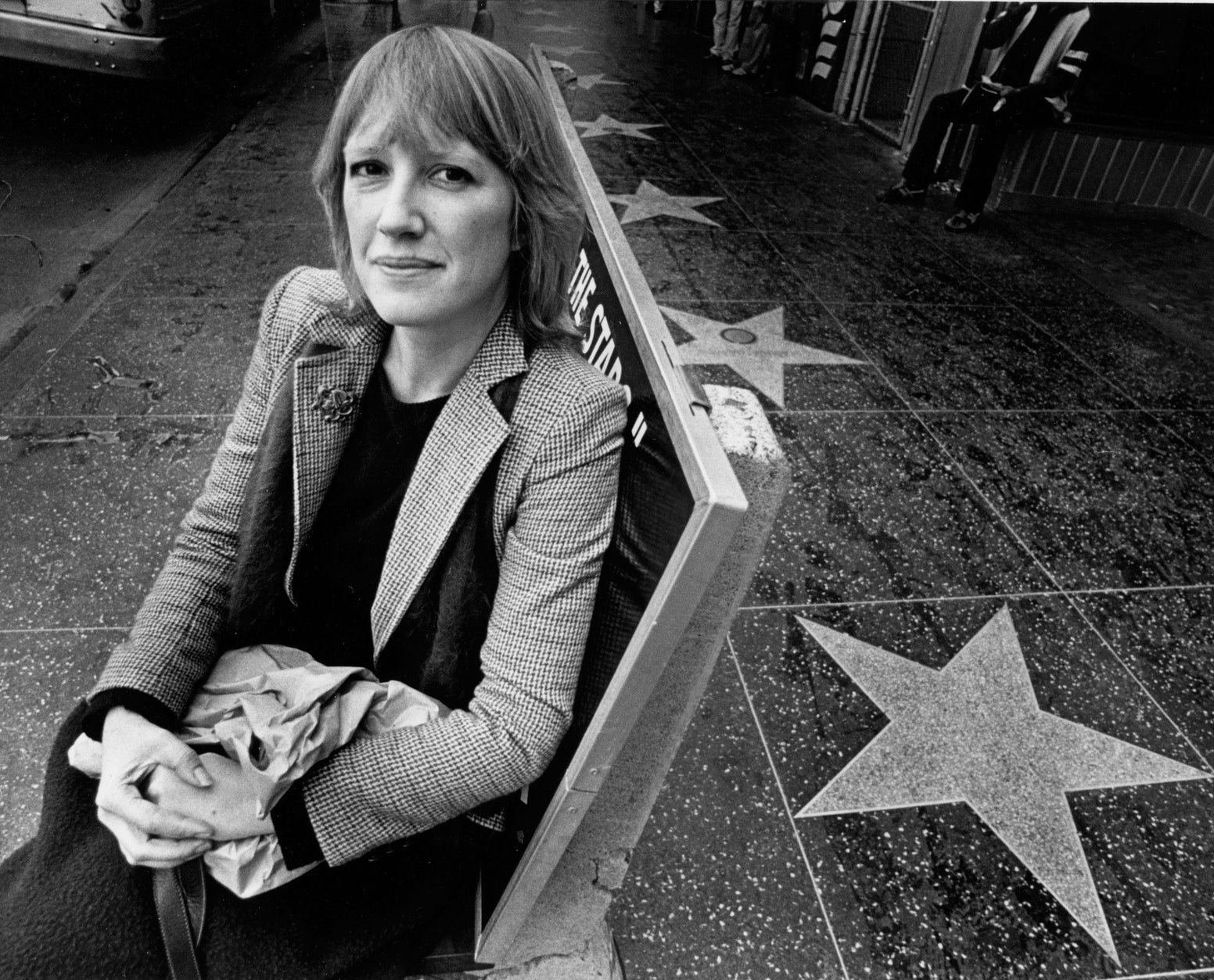

Born in 1943 to parents ensconced in Los Angeles’ proto-bohemian scene — her father was first violin in the orchestra at Twentieth Century Fox, and her mother was an artist — Babitz came of age amongst the likes of Igor Stravinsky (who was also her godfather), Greta Garbo, Charlie Chaplin, Aldous Huxley, and Bertrand Russell. She was beautiful — blonde and creamy-skinned, a marble Aphrodite witched into pliant softness — not to mention unapologetically vain (her books also incorporate a smattering of unfortunate remarks about dieting and her efforts to lose negligible amounts of weight).

In 1972, she started writing, and in 1974, Eve’s Hollywood was published. Then in her early thirties, she met her now-longtime agent, Erica Spellman Silverman. A memoirist first, the boundaries between fiction and nonfiction in Babitz’s writing are always elastic. But she is grounded by geography; at its core, her work chronicles her coming-of-age in Los Angeles, depicting the city as a rangy, sultry playground for women bewitched by their own youth and beauty. And yet, Babitz is sensitive to her city’s fundamental contradictions. Namely, its preoccupation with contrived beauty and glitz and its vulnerability to nature’s impositions: the hot gale winds of the Santa Anas, the earthquakes, and the fires. Her wholesale embrace of what is lovely and dangerous and absurd about Los Angeles appeals to contemporary readers. After all, the world Babitz depicts in her books of women roaming its streets and weighing their impulses very much remains the same, even if the landscape of the city itself has changed.

Babitz is sensitive to her city’s fundamental contradictions.

“In her writing, she makes it clear that she loves LA completely,” Variety’s Caroline Framke wrote to me. Framke, who lived in Los Angeles for six years, finds Babitz a site of resonant nostalgia. “It’s really refreshing to read someone who will celebrate the city at its most glamorous, tackiest, strangest. But even if I had never set foot in LA, she’s also just really fucking funny. Whenever I recommend her to someone now, I tend to go with the (probably unfair) shorthand of ‘she’s a funnier Joan Didion,’ though let’s be real, Eve just has more fun in general.”

Author and actor Mara Wilson, an Angeleno by birth, began reading Babitz last year after a friend supplied her with a few books. She also drew the Didion comparison, but, as Wilson observed, Didion wasn’t born in Los Angeles; she simply wrote about it. “I've had a complicated relationship with my hometown my whole life,” Wilson told me in an email, “and Eve is able to describe its idiosyncrasies like no one else. I’ve never seen LA explained so well, and in such gorgeous detail. She gets what I love about it, and what is frustrating and confusing about it.”

Babitz revels in Los Angeles’s basic illegibility and persistent thwarting of expectation, particularly when they spark East Coast elitist — coded as “civilized” — ire. She writes in Slow Days, Fast Company, “People with sound educations and good backgrounds get very pissed off in L.A. ‘This is not a city,’ they’ve always complained. ‘How dare you people call this place a city!’”

They’re right. Los Angeles isn’t a city. It’s a gigantic, sprawling, ongoing studio. Everything is off the record. People don’t have time to apologize for its not being a city when their civilized friends suspect them of losing track of the point.”

But as Babitz ages, the tensions that comprise the sinewy center of her city serve as a kind of barbed joke in her work. “That strange mixture that’s always been a major part of Hollywood — self-enchantment mingled with the ever-present fear of total disaster (earthquakes, fires, random murders) — lies beneath the physical reality of Hollywood, which sometimes looks too good to be true, as though we must have sold our souls to the devil for all those swimming pools and orange trees and young hopefuls basking in the sun,” she muses in Black Swans. “The idea of middle age — never mind old age, God forbid one hundred years! — is the violent opposite of everything Hollywood is based upon, which, as anyone can see, is and has always been beauty.”

Indeed, Babitz is also compelled by beauty, and the corporal pleasures to be found in it. Wilson and Washington, DC, gallery attendant Alessandra Dreyer perceive Babitz’s work as in concert with the zeitgeist particularly because of her unblushing treatment of sexual desire and feminine impudence. “In the past, people were much more likely either to shame or to fetishize women who wrote about sex and substances,” Wilson wrote to me. “It was shocking when, say, Erica Jong wrote about wanting to have consequence-free sex in the ’70s. But these are experiences people have, and perhaps more are willing to see women as people these days.” And maybe it’s a relief, this erotic audacity and unwillingness to perform civility or “niceness.” “Babitz pushes against niceness, showing how claustrophobic it can be,” Dreyer explained. “I think because of this expectation on niceness, women that may feel hamstrung by it can find a refuge in her world.”

Babitz’s confessional, sexually explicit delivery strikes Framke as a retroactive origin for the essays spilling across the internet over the last decade. “Her essays are sharp, but slyly ‘fluffy,’ she observed. “They’re so obviously and unavoidably personal, wrapping canny observations about industry and people and culture in salacious details about her life during some of LA’s juiciest times. Basically, she feels like the most obvious godmother of something like The Hairpin.”

Babitz’s sexual conquests have always been a natural source of fascination for readers. As a teenager, she wrote a fan letter to author Joseph Heller:

Dear Joseph Heller,

I am a stacked eighteen-year-old blonde on Sunset Boulevard.

I am also a writer.

Eve Babitz

By age 20 she had posed nude in a photo shoot with Cubism artist Marcel Duchamp. She dated Doors frontman Jim Morrison, comedian Steve Martin, and actor Harrison Ford (“The thing about Harrison,” Babitz has said, famously, “was Harrison could fuck.”). But of course, diminishing Babitz as the sum of her sexual conquests is both facile and absurd. Babitz’s appetites were diverse: She read Marcel Proust and Virginia Woolf, sang the praises of quaaludes, and knew precisely what to eat at every notable establishment in the city (for example, to delight in the perfect Bloody Mary she would direct us to the Musso & Frank Grill).

Yet cataloging Babitz’s multitudes has become its own kind of fetish, one that feels akin to a tacky fantasy about sexy librarians. We’re still dazzled by the notion of a woman who fucks and reads in equal measure, which is to say that she is persistently — myopically — treated as a rare entity. And while our literary icons are not always conventionally beautiful, it is undeniably au courant to be well versed in the works of a woman singularly comely and talented. Icons, after all, are fundamentally visual artifacts; they demand to be worshiped through a supplicant’s gaze.

However, this illusion of exclusivity, positing the rare breed of the Voluptuous Female Genius, isn’t merely tethered to antiquated bifurcations of feminine identity: the angel and the whore, the mousy bibliophile and the vamp. But in the American cultural imagination, smart, beautiful women are — still — often white; accordingly, these are the bodies in which we seek and hail the exceptional. It’s no surprise, then, that Babitz’s literary mythos is tied up in the privileges of conventional sex appeal.

To be sure, it’s oppressive for any woman to be force-fed clots of repetitive images: the same waifish body, milk-white skin, glinting, silken hair — but in this context, white women’s discomfort is born not entirely from garden-variety concerns of inadequacy. Babitz is aspirational to certain bookish women not merely because she is as smokin’ hot as she is poetic, she’s implicitly assigned as a prototype for beautiful genius.

But then, this impact ought to be expected. “I think I was expecting some level of white privilege [in Babitz’s work],” Wilson told me, “it’s pervasive in a lot of writing from that time. But I also think that there is a lot of classism that is not addressed. As much as I love [Babitz’s] depictions of LA, it’s not the LA that I grew up in, or that millions of lower socioeconomic status people and people of color grew up in. LA can be a very racially and economically segregated place.”

Babitz, however, is trading in a different sort of Angeleno fantasy: one that’s glamorous and sexy and staunchly homogenous. When she wrote to Joseph Heller, she knew that introducing herself as a blonde bombshell would secure his attention, and throughout her memoirs she breezily gestures to the irresistibility of her (white) curves. In Slow Days, Fast Company, she remarks, cannily and matter-of-factly, that the gleaming hue of her skin is largely responsible for the lust she inspires in men:

The truth is that when you’re as voluptuous and un-hair-sprayed as I am, you have to cover yourself in un-ironed muumuus to walk to the corner and mail a letter. Men take one look and start calculating how they can get rid of obstacles and where the closest bed would be … The reason for this is because my skin is so healthy it radiates its own kind of moral laws; people simply cannot resist being attracted to what looks like pure health.

For a woman like Babitz, there’s no paradox in “voluptuous” purity, no assumptions of lascivious excess that has contributed to the long exploitation of black women, from Sarah Baartman in the 19th century to the lingering racial stigmas of the present day. Babitz senses the potential danger of male sexual entitlement — she sheaths herself in “un-ironed muumuus” when she would prefer to be undisturbed. But still, her relative safety renders her tone flippant, insouciant: However implicitly, she understands that her desirability, potent though it may be, benefits from the protection of social favor. No matter how stacked, the glow of pure white health ensures that men, though they may pant after her, cannot take her simply because they desire her. She, after all, is art — fit for the Louvre, not an exotic curiosity held captive at a sideshow. Her beauty is meant to be a source of power, rather than a liability.

As Dreyer remarked to me, Babitz is not merely “charismatic and pleasure-seeking,” but also “able to use the cover[s] of youth and whiteness to manipulate problems away ... because of the privilege of being the feminine default in Western culture, she always had a safety net that could be activated.”

In Slow Days, Fast Company, Babitz claims “sex is our art,” and so she records her memories of lusty encounters as if they are populated by marble-white figures made suddenly warm by breath and blood. She raves about the pleasure of these venerated bodies, both her own and those of her lovers. In the story “Expensive Regrets” from Black Swans, Babitz recalls her friend Vicky, with whom she sometimes tumbled into bed: “[She] pushed me back on the bed, threw off her clothes, and the next thing I knew, I was in this sensually divine taboo tableau that went from curiosity to lust really fast, her white body reflecting the moonlight like a pure lily doing impure things.” She describes Renzo, a fellow writer who has come to town to consummate their flirtation in the sober 1990s, as “an elegant vampire.”

As Babitz drives him through LA, they learn from a radio news report the verdict of the Rodney King trial. Four police officers, three of whom were white, had been charged with brutally beating King — and on April 29, 1992, they were acquitted. Disgusted, Babitz switches off the radio. “I can’t listen to this,” she tells Renzo, and then promptly brings up a more pleasant subject. Later, they retire to his room at the Chateau Marmont, passing days and nights in a darkened cocoon spun out of libido and bedsheets: “With his white skin and shiny wet black hair, things just marbleized into unbridled fiery endlessness, almost as if we lay in smoke.”

When, after a few days, the lovers emerge from the bed, Babitz learns that the smoke that seemed to emanate from their entwined bodies was real, but that its origins were the riots that had raged with ferocity since Los Angeles had learned of the shameful acquittal. “It was then that we found out about the city,” Babitz writes, “how it had, in our absence, gone up in smoke. The smoky smell was smoke. The silence was the curfew.”

As she chronicles the following days, in which she and Renzo parse the aftermath, Babitz mourns the devastation of her city and stares aghast at footage of the looting on Hollywood Boulevard, including lingerie retailer Frederick’s of Hollywood. “It struck me that I’d been having too swell a time to get away scot-free, but this seemed too much of a price to pay, I love Frederick’s!” she bemoans.

A remark like this might give the impression that Babitz cannot be troubled to take these riots — and what they mean — seriously, but her prose often leans into the juxtaposition of folly and careful reflection. She is, we learn, in favor of police reform and disgusted by politicians like Ted Kennedy, who, rather than enact progressive measures, cravenly leaves a young woman to drown in the ocean. Since Nixon’s resignation, she explains, she had expected more than these surges of injustice.

And yet, she turns off the radio. She goes to bed with her lover for four days without so much as glancing at a headline. Ultimately, the horror of the riots supplies a backdrop, a striking juxtaposition for a story centered on Babitz, the aesthetics of full-throttle lust, and her fancifully self-absorbed notion that “maybe if I’d been home, none of this would have happened!”

In claiming the sprawl of Los Angeles as her own, Babitz dreams up an intimacy so thick that the relationship is mutually influential — that she has become a needful, talismanic body within the ecosystem capable of shielding the city from tragedy. It’s a well-traveled sentiment — protecting one’s home is a near-feral impulse — and one born from love, but the presumption is nonetheless insidious. After all, whatever Babitz may know of Los Angeles, she writes almost exclusively about places that are beautiful, whitewashed, and thrilling, which, in turn, reinforces a finite vision of Los Angeles that has become iconic in popular culture. Twenty years later these elisions and assumptions are especially glaring, as is her disinclination toward politics, but Babitz’s work is first and foremost historical — that is to say, we need not make excuses for Babitz, but to fully condemn her would be anachronistic. The limitations of her work, and of her perceptions, do not negate her literary importance. The world she renders for us is always worth dwelling in, even skeptically.

In the last 10 years, Babitz’s politics have allegedly snapped to the right. But as Framke observes, you can track this shift across her work, both in terms of tone and her burgeoning preoccupation with bygone dissipation. “As I’ve been moving along chronologically in her books ... I’ve noticed her writing get more reflective towards the past, less in love with the studied carelessness of being young and hot and down for a good time,” she wrote to me. “And maybe the more she wrote about the LA and world she once loved so much, the more she resented what it all became even more. For all her big talk about indulging a hedonistic lifestyle, her writing really did value tradition and consistency ... more than she maybe realized.”

Of course, Babitz is not the first literary figure to show her readers a gilded Los Angeles experience, hedonistic or not, and her newly conservative politics by no means demand that we permanently shelve her books. The mind needs respite in the midst of outward turmoil; who doesn’t enjoy a well-staged Instagram shoot? We should escape into Eve Babitz’s honey-sweet, glittering world if we want to, so long as we aren’t dazed by the warm lights making false promises: that the exploits of young white women are the defining stories for women at large, and that they alone can be anointed as our icons. We can love Eve Babitz and relish her dizzying, seductive legacy — but we can, we must, open our aperture on whose stories deserve commemoration, and on which persons are hailed and exalted as It girl. ●