Last week, after the Indian government turned off access to the internet from mobile devices in state after state as furious protests erupted over an anti-Muslim citizenship law, I sent a WhatsApp message to a colleague in panic.

“Is there any chance in hell that Delhi would lose internet?”

For days, I had watched as authorities plunged districts across the country into digital darkness. On December 10, far-flung districts in the northeastern states of Arunachal Pradesh and Tripura went offline, followed a day later by parts of neighboring Assam. The authorities had shut off internet access to try to stymie protests against a law passed that week by India’s Hindu nationalist government, which made getting an Indian citizenship easier for immigrants who practice all major South Asian religions except Islam. People opposing the law say that it destroys India’s secular ethos.

Internet shutdowns in India are not new. For years, local, state, and national authorities across the country have been turning off the internet at the first sign of trouble. Last year, they shut it down in the state of Rajasthan during exam season simply to prevent students from cheating. And Kashmir, whose legal autonomy the Indian government suddenly took away earlier this year, has been under digital siege since August, making it the longest internet shutdown ever in a democracy.

Still, I thought, it couldn’t happen in the capital, could it? Delhi, after all, is home to not just me, but more than 20 million people, the Indian Parliament, national and international media, diplomats, and more.

“No I don’t think so,” my colleague replied.

On a freezing Thursday morning, days after our conversation, people across New Delhi started tweeting about dead networks. At first, there was confusion, then, shock and anger, as India’s largest mobile networks scrambled to explain: They were following a police department order that directed them to turn off voice, SMS, and internet services in dozens of Delhi neighborhoods “in view of the prevailing law and order situation.”

The shutdown in Delhi meant that protesters like 37-year-old Shakaib Azhar Chaudhry had trouble using their phones to mobilize. Chaudhry, an education consultant who participated in five protests in New Delhi the week he spoke to BuzzFeed News, is a part of six WhatsApp groups where dissenters share information regarding people’s legal rights when arrested by police, the best exit routes, news updates, and more. Last week, when protesters in New Delhi read the preamble to the Indian Constitution, most people pulled up a copy shared in WhatsApp groups they happened to be in, he said.

“The internet becomes a support system in times like these,” Chaudhry said and added that he was opposed to the new law because it singled out Muslims like him.

Eight years after India had its first internet shutdown, it had finally reached the national capital. What had once been used to control the peripheries was now being used to control the core.

What had once been used to control the peripheries was now being used to control the core.

At the beginning of the decade, just over a hundred million Indians were connected to the internet. Few people in the country could afford desktop computers, and broadband was prohibitively expensive. At the close of the decade, more than half a billion Indians are online. Some of that explosion has been a result of efforts of Silicon Valley giants like Facebook and Google to bring the “next billion” online — in the middle of the decade, Google brought free Wi-Fi to hundreds of Indian railway stations, while Facebook set up thousands of inexpensive hotspots in rural parts of the country.

But in the last few years, cheap data, thanks to a telecom war that slashed prices to pennies, and a glut of inexpensive Android smartphones have made India the world’s fastest-growing internet market — and Silicon Valley’s wet dream. In the 2010s, the country went from digital wasteland to megalopolis. Suddenly, we had Uber! Amazon! Prime! Alexa! Netflix! YouTube that you could watch without buffering! Swiping right! Our very own unicorns that delivered meals and let us zap money digitally! High. Definition. Porn!

“The changes that the smartphone brought to the West were incremental,” Ravi Agrawal, CNN’s former Indian bureau chief and author of the book India Connected, told BuzzFeed News. “If you were a middle-class American, chances are that you already had a PC, a telephone line, a camcorder, a music player. Getting a smartphone consolidated the things you already had.” For Indians, he said, the smartphone was people’s first camera, television, library, and newspaper. “For Westerners, the smartphone has been evolutionary, but for Indians, it has been revolutionary.”

“To young Indians today, smartphones represent literal and figurative mobility,” wrote Agrawal in his book. “The smartphone is the embodiment of the new Indian Dream.” When I spoke to him, Agrawal called the smartphone the “most transformative development in the last 10 years in India by far.”

But as India, ruled by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s BJP, slid deeper into authoritarianism, the smartphone is now powering a different transformation — for millions of young Indians, it has become a device for dissent.

The first time Modi won election in 2014, fewer than 300 million Indians were online. Modi rose to power on a wave of nationalism and bright promises to lead the country into economic prosperity. But the BJP was also the first major political party in India to use the internet and social media to gauge public opinion and build support. The Financial Times called him India’s first “social media prime minister.”

In a blog post published soon after he won, Modi wrote: “This is the first election where social media has assumed an important role and the importance of this medium will only increase in the years to come.” He added that “our party, our campaign and me personally have gained tremendously from social media.”

That remark would be prescient. On the internet, Modi’s reign has been marked with extreme polarization, orchestrated harassment campaigns against critics, and a deluge of misinformation and propaganda that party supporters pump into private WhatsApp groups. “Proud to be followed by @narendramodi” read the Twitter bios of hundreds of the prime minister’s most fervent supporters.

“India used social media to infect its democracy much before the Trump election,” said Mishi Choudhary, founder of the Software Freedom Law Center, a legal advocacy organization that works in the internet policy space in India. “They really understood how to use social media to control narratives about the economy or their policies.”

“India used social media to infect its democracy much before the Trump election.”

But the internet boom in India in the last few years also birthed a new kind of influencer: the young digital dissident.

Since the protests began in the second week of December, Aranya Johar has been spending entire days glued to her Android phone. The 21-year-old slam poet and Instagram influencer, who lives in Mumbai, had been posting about feminism, gender, and sex positivity for her audience of nearly 100,000 people. But now, as she flicks open her phone’s settings and clicks on the screen time feature, which keeps track of usage, the number surprises even her: an average of 12 and a half hours every day since the protests started. Johar has been using her platform to amplify anti-government voices and information about upcoming protests.

“It’s a moral responsibility for me,” she told BuzzFeed News. The bar graphs indicating which apps she used the most rose and fell — on the first day of protests, her most used app was YouTube, but as she tracked the news, swapped information with friends, and posted pictures from protests she attended, her list became dominated by Twitter, WhatsApp, and Instagram.

Friends, please remember that we have WhatsApp stories and Facebook at our disposal. Feel free to share news there so that it reaches people. If you are feeling helpless, understand that sharing information is a great way to help.

Dhruv Rathee, a 25-year-old Indian, lives “somewhere in Europe” (Rathee said he prefers to keep his location private). In the last few years, Rathee has become one of India’s top YouTubers by posting videos busting government propaganda, critiquing BJP policies, and fact-checking misinformation spread online by government supporters. At the time of publishing, he had 2.72 million YouTube subscribers, over 400,000 Twitter followers, and more than 910,000 followers on Facebook. In his videos, Rathee looks straight into the camera and breaks down his analysis in simple Hindi with English subtitles. Most videos get millions of views.

Eighty-five percent of his viewers in India watch him on their mobile phones, Rathee told BuzzFeed News, and said that he sees a direct correlation between the rise of Modi, the explosion of internet users in India, and his own popularity on the internet.

“I think I am also popular because India’s mainstream media has become worse and worse over the years,” he said. India’s media has been criticized for cheerleading the Modi government ever since he became prime minister in 2014. “People who seek criticism of the government can’t find it on television channels or newspapers. That’s why they see us on the internet as the only alternatives. I don’t think I would have become this popular if the media was doing its job.”

Others, like Kunal Kamra, have built thriving careers in stand-up comedy by risking the wrath of BJP supporters and viciously poking fun at the prime minister and BJP apparatchiks on his Twitter account with more than 660,000 followers. Each of Kamra’s zingers against the government gets thousands of likes and retweets on Twitter. Last week, Kamra got the last word in a quote-tweet battle against a BJP spokesperson, tweeting: “BJP is Nazi Germany.” The tweet got more than 34,700 likes and 8,000 retweets. Kamra didn’t respond to requests for comment from BuzzFeed News.

More recently, the BJP itself has begun targeting digital dissidents directly from its official channels. In a propaganda video tweeted from the party’s official handle on Wednesday, the BJP said that all “Instagram celebrities” who push back against the government are doing it to be “woke” and because they need “cool topics for their New Year parties.”

“What we think of as the ‘internet,’ even 10 years ago, was the American internet, and that is what everybody experienced.”

None of this would have been possible at the beginning of the decade. Despite some early efforts from American tech companies to bring Indians online, the scales didn’t tip until oil tycoon and Asia’s richest man Mukesh Ambani, who lives in a 27-story house that towers over the slums of Mumbai, bankrolled telecom carrier Jio with $35 billion. In 2016, Jio started giving away high-speed data to millions of Indians for free and kicked off a telecom war that made Indian data prices the cheapest in the world. Experts say that Jio was an inflection point. “If Jio hadn’t happened, internet adoption in India would have been much, much slower,” said Agrawal, the author. “I don’t think the world has seen anything like this — one company just bombarding the market with free data the way Jio has.”

But fast-tracking millions of Indians onto the internet hasn’t been as easy as throwing free data at them. A large part of that revolution was made possible by one of the largest tech companies in the world: Google.

For years, India wasn’t on the radar of most American tech companies. “The only times India came up during product discussions was customizing those products on slow and patchy internet networks in developing countries,” said a longtime Google executive who didn’t wish to be named. “What we think of as the ‘internet,’ even 10 years ago, was the American internet, and that is what everybody experienced.”

That started changing just a few years into the decade. Once they saturated developed markets like the US and the UK, tech giants realized that the next phase of growth would have to come from emerging markets like India, where nearly 900 million people were still offline. "We're not here for a quarter or a year, or a few years. We're here for a long time. For hundreds of years," said Apple CEO Tim Cook during a visit in 2016. But he may have been too late.

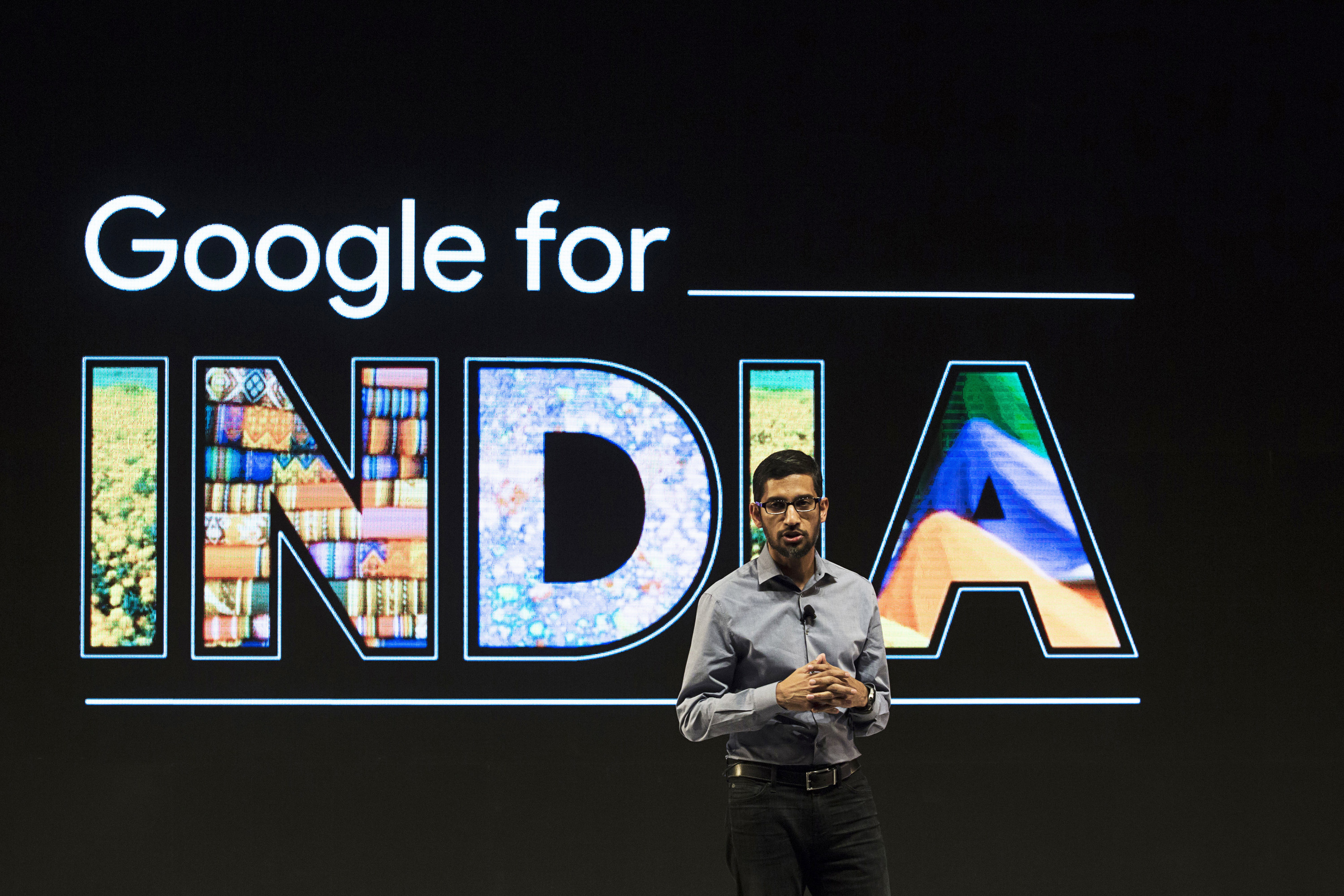

In October 2015, a lanky, bearded Indian called Sundar Pichai became Google’s CEO. Just two months later, Pichai, along with dozens of top Google executives, flew to New Delhi. There, Pichai had a closed-door meeting with Modi, dined with India’s then-president Pranab Mukherjee at his palatial, colonial-era residence, interacted with thousands of students in an auditorium, and made a series of India-specific announcements — an expansion of Google’s Hyderabad campus! A ramping up of Google’s engineering presence! Free Wi-Fi at Indian railway stations! Training rural women to use the internet! — at a splashy event called Google for India, which has since become an annual extravaganza.

“Our goal is to bring all Indians online — regardless of income, region, age, gender, or language — and as they come online, we want to make the internet more relevant and useful for their needs,” said Pichai at the time.

Google had already announced a few India-specific initiatives like low-cost Android One phones and letting Indians download YouTube videos a year earlier. But flying the new CEO to his home country was a turning point for the company.

More so than Apple, Google shaped the modern Indian internet. The company went to the grassroots and got its hands dirty, doing more than throwing free Wi-Fi at Indians. Over the last few years, Google has made its products available in more than a dozen Indian languages, reworked Android keyboards to work better with Indic language scripts, and even trained its voice assistant to understand Hinglish, a mixture of Hindi and English that millions of Indians use colloquially, which trips up Alexa and Siri regularly.

It made Google Maps work offline and launched Google Pay, a made-for-India payments app that now dominates digital payments in the country. When millions of Indians use an internet-enabled smartphone for the first time, more than 90% of devices run Android, Google’s mobile operating system.

“We realized that when we build for India first, those features work better elsewhere, because it’s a much bigger market,” Google Pay senior director Ambarish Kenghe told BuzzFeed News. “The kind of heterogeneity you find here is hard to find anywhere else.”

And during the last few weeks, hundreds of Indians shared Google Maps links directing people to precise protest locations. A fundraising web page for student protesters injured by police brutality let Indians pay through a handful of digital payment options including Google Pay.

In the last month of the decade, as the Modi government faced the strongest dissent it has ever faced, cheap internet — and Google’s products — powered the revolution. Back in California, Google has come under increasing protest, but here in India, it still powers the demonstrations.

When the internet went down in the capital, Apar Gupta, director of the Internet Freedom Foundation, a New Delhi–based nonprofit that works in areas of free speech, online freedom, and privacy, said he was worried about the larger point the government was sending its citizens. “There are concerns about us not being in control, but actually being small widgets that are being turned on and off in a larger machine serving either the interest of large Silicon Valley corporations or authoritarian governments, just pieces being moved around on a chess board,” he said.

In India, shutting down the pipes that power dissent has been the go-to move for officials, big and small, for years. According to the Software Freedom Law Center, which tracks internet shutdowns in the country, India tops the world in digital clampdowns. By its estimate, India had turned off the internet in various parts of the country 376 times at the time this article was published — 104 times in 2019 alone.

“It’s not as if previous governments in India haven’t to do tried this,” said Gupta. “But the present government, especially, is very intent on political control over large sections of the Indian population and views the internet as a very important instrument in doing that. This is a level of authoritarianism that reeks of a Chinese model, which is very antithetical to India’s democratic values.” Indeed, the same day that India turned off the internet in large swathes of its capital, People’s Daily, China’s state-run mouthpiece, published an article that pointed to India’s internet bans to justify China’s own internet shutdowns in volatile Xinjiang.

"This is a level of authoritarianism that reeks of a Chinese model, which is very antithetical to India’s democratic values."

Indian authorities have justified their country's shutdowns by saying turning off the internet prevents rumors and misinformation from spreading on platforms like WhatsApp and Facebook.

But last week, when a court in the state of Assam ordered the state’s government to restore internet access, it said that the government hadn’t provided any evidence that this actually happened. “Shut down of mobile internet service[s] virtually amounts to bringing life to a grinding halt,” the court said.

Some of the worst violence during the ongoing protests occurred in Uttar Pradesh, an Indian state led by a Hindu cleric, and home to 43 million Muslims. At least 17 people, including an 8-year-old boy, were killed in the state, even as law enforcement personnel denied allegations of police brutality. A HuffPost India report published on Wednesday revealed how state police detained and tortured children, some as young as 13 years old. On WhatsApp, rumors about Uttar Pradesh flew thick and fast, but it was difficult to gauge the true extent of the horror: Authorities banned the internet in at least 22 Uttar Pradesh districts.

If you want to see how retaliatory actions by the state are essentially anti poor, step outdoors in Uttar Pradesh towns today. Poor need phone data. Middle class/elite have wifi. Vendors entirely missing from streets. Glass front stores open. A day's wage lost is starvation here.

“With governments, the desire to control is universal,” said Choudhary. Last week, the day the internet was turned off in Delhi, Choudhary said that the SFLC office in the city got an anonymous threatening phone call, telling them to stop tracking shutdowns.

By controlling the tools through which millions of Indians organize, mobilize, push back, protest, and protect, India’s powerful try hard to stomp out dissent — and to stop out the fragile feeling of solidarity that has united Indians across religions since independence.

“Why are you othering us? Why are you making us feel like outsiders when we also participated in the Indian freedom struggle?” said Shakaib Azhar Chaudhry, the education consultant.

Today, Delhi is seeing its first internet shutdown. The wall has been breached, it has never happened in a metropolitan city before. Shutdowns are supposed to be last-resort tools for public emergencies, not weapons to prevent dissent. #internetshutdown #CAAProtest

And yet, despite the internet shutdowns, India, whenever and wherever it could, protested online.

“Get your protest buddies to download Bridgefy,” someone tweeted, referring to an app that uses a phone’s Bluetooth connection to let you chat with other users around you. “The more the users, the longer the range,” said another. “It will come handy when the government decides to turn off the internet in your area.”

“Why are you othering us? Why are you making us feel like outsiders when we also participated in the Indian freedom struggle?”

A loose group of artists called Creatives Against CAA (an abbreviation for Citizen Amendment Act, the name of the anti-Muslim law) set up a website where it uploaded high-resolution posters under a Creative Commons license for anyone to print and take to protests, while later in the week, an exhaustive “cheat sheet for responding to state propaganda” went up, full of tips, tricks, and FAQs to convince government supporters (like friends, uncles, and extended family, for instance).

On Sunday, ordinary Indians poked holes in a fiery speech that Modi gave at an election rally in New Delhi on Twitter, and showed that it was full of lies. The tweets went viral, and shortly after, the term #ModiLies trended on Twitter in India.

Someone on Instagram created CAA-bashing “Good morning” style WhatsApp forwards, popular with Indians.

On Friday evening, a crowdsourced Google spreadsheet of medical professionals to call in an emergency zipped through dozens of WhatsApp groups full of angry young protesters. “Please amplify this!” became a popular request.

“Please come join us immediately at Daryaganj police station,” read someone’s Instagram story, screenshots of which were immediately shared in WhatsApp groups. “There are people inside and the police are denying that. Bring your lawyer, doctor and influential friends. Come asap.”

Some Indians urged each other to link their phone numbers to their Twitter accounts so they could use a little-known Twitter feature that lets you tweet by sending an SMS in case the internet went down.

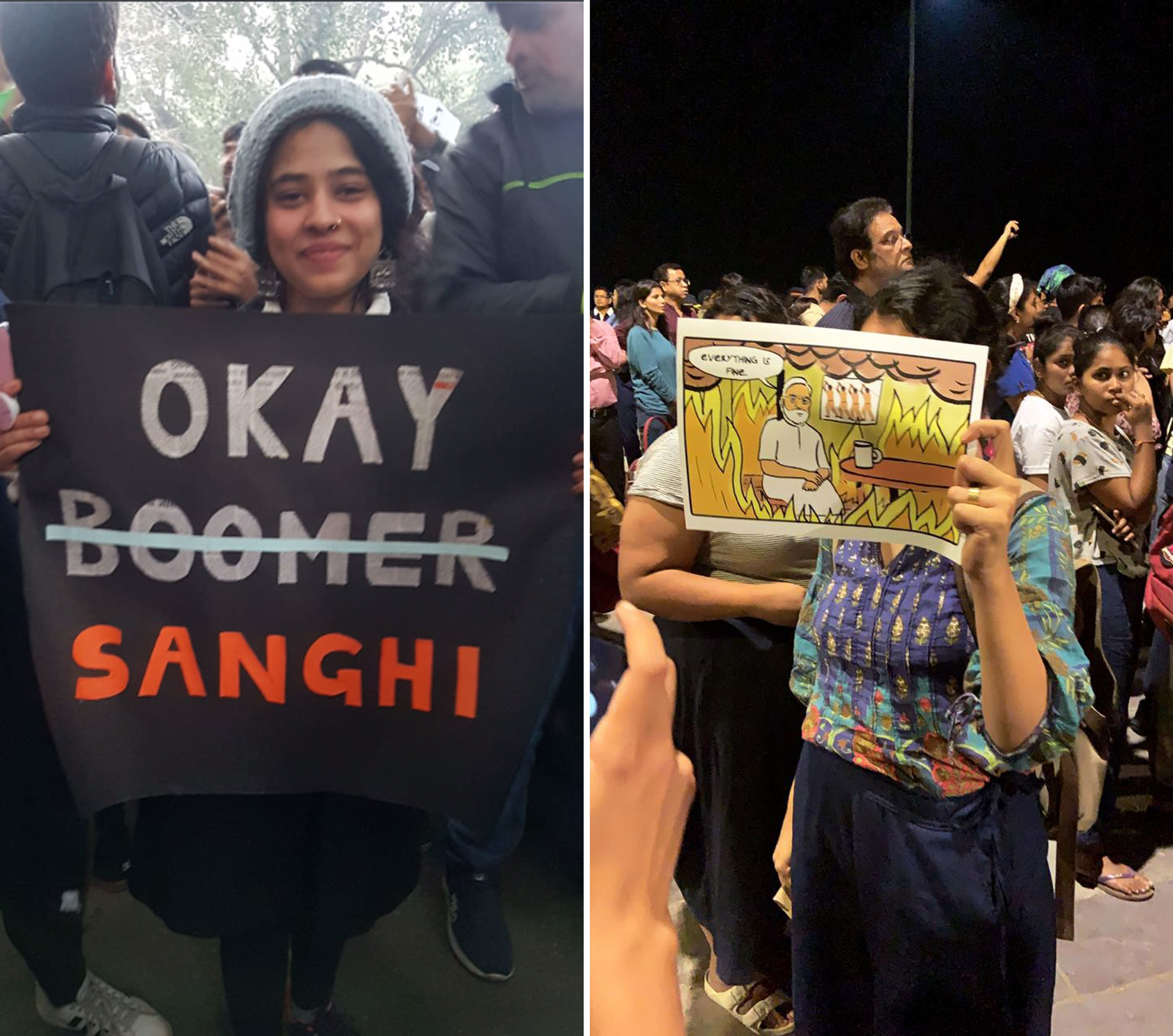

And at some protests, the internet itself trickled down into the real world. “OK 𝙱̶𝚘̶𝚘̶𝚖̶𝚎̶𝚛̶ Sanghi,” read a poster, modifying a viral cultural catchphrase to refer to a pejorative word for Modi supporters. A 2015 meme in which Gordon Ramsay holds talk show host Julie Chen’s head between two slices of bread while yelling “What are you?” (her response: “an idiot sandwich”) made its way to a poster with Chen’s head replaced by India’s Home Minister and Modi’s right-hand man, Amit Shah. A young girl carried a poster of the viral “This Is Fine” meme with the dog engulfed by flames replaced by a caricature of Modi.

“Fascism fuels creativity,” said Sukhnidh Kaur, a student from Mumbai who is a part of a WhatsApp group that is against the new law.

Last week, a 2013 tweet from Modi, long before he became prime minister, suddenly went viral. “A question,” it said. “Where do you see India in 2020?”