In February 2017, Microsoft announced Skype Lite, a brand-new edition of Skype just for India. A more spartan version of Microsoft’s marquee messaging service, Skype Lite is designed to run well on cheap Android phones and to handle calls over flaky 2G data networks — the trappings of an app made by a large, wealthy corporation for a large and largely poor emerging market. But that’s not all it does.

Skype Lite also taps into a giant government-owned database filled with the demographic and biometric records — names, dates of birth, addresses, phone numbers, photographs, iris and fingerprint scans — of more than a billion Indian citizens.

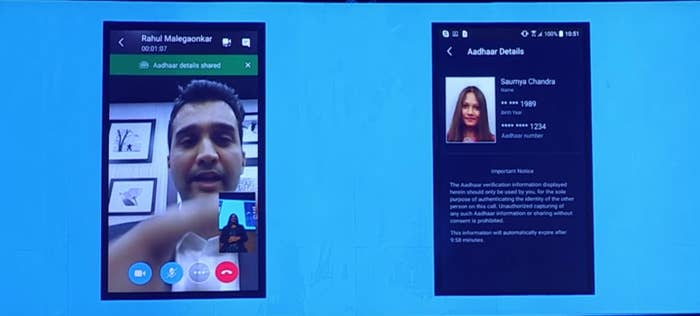

Touting that feature onstage at a launch event in Mumbai, Microsoft's executives offered the most vanilla of demos: a job interview over Skype.

“If I want to hire somebody, I would feel more comfortable knowing that I am indeed talking to the right candidate,” said Skype engineer Rahul Malegaonkar. To do that in in Skype Lite, he explained, all an interviewee would need to do is punch in their 12-digit government-issued UID — short for unique identifier — which the app would check against the government database.

Some 1.12 billion Indians — more than 99% of citizens over 18 — now have UIDs thanks to this authentication system. It’s called Aadhaar — “support” or “foundation” in Hindi — and it is the largest, most ambitious national identity program in the world.

When it was first rolled out in 2009, Aadhaar was envisioned as a voluntary identity system that would help the Indian government crack down on fraud in the country's notoriously corrupt welfare system. But over the years, it's become effectively mandatory as the government and private sector alike rely on it to provide all manner of identity-linked services to India’s vast and diverse population. Now, less than a decade after its debut, Aadhaar is, for many Indian citizens, a proverbial "one ID to rule them all." Not only is it a means of accessing India's welfare system, it's tied to everything from banking and internet services to international travel and marriage registration — and, of course, Skype.

Onstage at the company’s Mumbai event, Malegaonkar’s Skype Lite app displayed a large green checkmark along with dummy name, address, and date of birth information.

“Yep, it seems like we have a match,” he exclaimed, as the audience clapped wildly.

Meanwhile, India’s privacy experts rolled their eyes. “A proprietary software company harvests personal information from a centralized government database using unaudited technology in a jurisdiction without a proper privacy or data protection law,” said Sunil Abraham, director of the Centre for Internet and Society (CIS), an influential Bangalore-based think tank. “Sounds perfect to me!”

A Microsoft spokesperson assured BuzzFeed News that Skype Lite was compliant with local regulations. “We don’t store any users’ Aadhaar information,” the company explained. “Rather, we pass [the details] through to the government’s central Aadhaar database.”

Who am I?

For millions of Indians, government-vetted identification has been elusive for decades. This is particularly true in India's most impoverished regions, where a lack of simple birth or address documentation can lock people out of crucial services many take for granted — bank accounts, insurance, pensions, government services. With a very simple set of objectives, Aadhaar was designed to change that. It would provide every Indian with an official identity, and it would allow government agencies and private companies like Microsoft to authenticate that identity by plugging into a set of software application interfaces called the India Stack.

In 2009, the Indian government established the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) under the country’s IT ministry and tapped Nandan Nilekani, billionaire and co-founder of IT services juggernaut Infosys, to oversee it. Nilekani called Aadhaar a "turbocharged version of the Social Security number," and a year later, the agency began collecting citizens' demographic data — names, addresses, photographs, mobile numbers, iris scans, and all 10 fingerprints — and adding it to a centralized database.

Pitched as a panacea to welfare fraud by India’s ruling Congress party, Aadhaar was lauded by some of the biggest names in technology. Bill Gates called it a “world-class digital foundation,” and Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella said it was “pretty tremendous.” The Wall Street Journal called it “the most technologically and logistically complex national identification effort ever attempted." After decades of being invisible, India’s poor would now simply authenticate themselves through their irises or fingerprints to receive their share of subsidized food and cooking fuel. The corruption that had plagued India's welfare system was done for.

But in the years that followed, an increasingly vocal group of privacy activists, security experts, and citizens raised concerns about the implications of creating a vast database of biometric information for the population of an entire country. "Aadhaar is being converted into the world’s biggest surveillance engine," Indian news website Scroll warned in a recent opinion piece.

And other critics sounded an equally troubling note: With the most intimate details of over a billion people in a database, what if Aadhaar were to be hacked?

No way out

“Indians have historically had different sets of information stored across different databases, such as their bank accounts, driver’s licenses, passports, accounts with cell phone carriers, and more,” said Nikhil Pahwa, editor of Indian technology news website MediaNama and a staunch Aadhaar critic. Traditionally, these weren’t linked to one another. “What Aadhaar aims to become is a single ID linking your entire life across dozens of these databases together,” he said. “This allows it to be used for mass surveillance and targeting very easily.”

While India's Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled that Aadhaar numbers are not and cannot be required of the country's citizens, it's becoming increasingly difficult to get by without one. Indeed, Aadhaar's critics complain that the Indian government has been shrewdly pushing it into broader usage by requiring it for things like driver's license applications and renewals, and soon cell phone numbers.

Last month, the government passed a finance bill making it mandatory for every Indian who files tax returns to input their Aadhaar number. Asked if the government was forcing citizens to get Aadhaar despite the Supreme Court mandate, finance minister Arun Jaitley replied simply, “Yes, we are.”

In the future, Indians may be required to use Aadhaar to log on to public Wi-Fi hotspots, buy train tickets, access bank accounts, withdraw pension money, use matrimonial websites, and buy tickets for cricket matches — among other things.

Critics paint a grim picture of India with mandatory Aadhaar: an Orwellian state with every action of every citizen under constant scrutiny at all times.

Got it. It is compulsorily mandatory to voluntarily get yourself an Aadhaar card.

“All this is illegal and is in contempt of the Supreme Court,” Usha Ramanathan, a legal researcher and activist who has been a vocal opponent of the Aadhaar project ever since it launched, told BuzzFeed News. “The Aadhaar project is less about technology and more about technocracy.”

In November 2016, Ramanathan organized a daylong session in New Delhi that was attended by more than 50 people — lawyers, activists, social workers, researchers, academics, and journalists — to draw up a plan to spread awareness about privacy issues related to the Aadhaar program.

"Aadhaar is a sitting duck."

“Aadhaar alters the relationship between the citizen and the state,” said Shyam Divan, a Supreme Court lawyer who has been fighting the project in the country’s highest court for years, and who was present at the event. “It’s concerning, because it tilts the balance so steeply in favor of the government.”

That concern is well grounded in reality. In March 2016, India’s parliament passed legislation giving federal agencies access to the entire Aadhaar database — all billion-plus names, fingerprints, irises, mobile numbers, addresses, and photographs — in the interest of “national security.” In February, the UIDAI was accused of trying to silence critics by filing a police complaint against a writer who wrote about the project's data security vulnerabilities. And in March, the agency filed a criminal complaint against a television journalist who aired a segment showing how he was able to use a fake name along with his real one to get two different Aadhaar numbers.

"You can't change your fingerprints"

Sunil Abraham, the CIS director, calls himself a “technological critic” of the Aadhaar platform. For years, he’s been warning of the security risks associated with a centralized repository of the demographic and biometric details of a billion or so people.

"Aadhaar is a sitting duck," Abraham told BuzzFeed News. That's not an unreasonable assessment considering that India’s track record for protecting people’s private data is far from stellar. Earlier this year, for example, a security researcher discovered a website that was leaking the Aadhaar demographic data of more than 500,000 minors. The website was subsequently shut down, but the incident raised questions about Aadhaar's security protocols — particularly those around data shared with third parties.

Yesterday I was informed about a website which was publishing #Aadhaar numbers of minors. We informed the authoriti… https://t.co/GBqrzfBY3R

Abraham’s concerns are not without global precedent. In 2012, Ecuadorian police jailed blogger Paul Moreno for breaking into the country’s online national identity database and registering himself as Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa. In April 2016, hackers posted a database containing names, national IDs, addresses, and birth dates of more than 50 million Turkish citizens, including Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan; later that month, Mexico’s entire voter database — over 87 million national IDs, addresses, and more — was leaked onto Amazon's cloud servers by as-yet-untraced sources; and in the Philippines, more than 55 million voters had their private information — including fingerprints — released on the Dark Web.

“When this database is hacked — and it will be — it will be because someone breaches the computer security that protects the computers actually using the data.”

“What is the price that we pay as a nation if our database of over a billion people — complete with all 10 fingerprints and iris scans — leaks?” Abraham asked. The consequences, he said, will be permanent. Unlike a password, which you can reset at any time, your biometrics, if compromised, are the ultimate privacy breach. “You can’t change your fingerprints.”

The UIDAI claims that the Aadhaar database is protected using the “highest available public key cryptography encryption (PKI-2048 and AES-256)” and would take “billions of years” to crack.

“Encryption like this doesn’t typically get broken, it gets circumvented,” security researcher Troy Hunt told BuzzFeed News. “For example, the web application that sits in front of it is compromised and data is retrieved after decryption.” Or alternatively, he said, the encryption key itself is compromised. “Naturally, governments will offer all sorts of assurances on these things, but the simple, immutable fact is that once large volumes are centralized like this, there is a heightened risk of security incidents and of the data consequently being lost or exposed,” he added.

Cryptographer and cybersecurity expert Bruce Schneier echoed Hunt’s assessment. “When this database is hacked — and it will be — it will be because someone breaches the computer security that protects the computers actually using the data,” he said. “They will go around the encryption.”

Nilekani — who did not respond to BuzzFeed News' requests for comment — recently dismissed concerns around the project’s privacy implications as “hand-waving.” In an interview with the Economic Times, he repeatedly stressed how secure Aadhaar’s “advanced encryption technology” was. “I can categorically say that it’s the most secure system in India and among the most secure systems in the world,” he said.

Abraham is unconvinced by such assurances. He believes Aadhaar fundamentally changes the equation between a citizen and a state. “There’s a big difference between you identifying yourself to the government, and the government identifying who you are," he said.

No fingerprint, no food

Fingerprint scanners may work quite well for limited applications in urban bubbles, but here’s the thing: The technology simply hasn’t been tested at scale with a billion-plus users from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. In other words, Aadhaar is really the first effort of its kind — and it’s rural India that’s bearing the brunt of the stress-testing.

In the Indian state of Rajasthan, for instance, Aadhaar scanners have regularly failed to recognize weathered fingerprints of elderly people and manual laborers. Many of these people didn't get their share of food subsidies as a result.

Last November, T. Peter, secretary of India's National Fishworkers Forum, complained publicly that thousands of fishermen who use fishing nets are often rejected by Aadhaar fingerprint scanners because of the micro-abrasions nets leave on their fingers. They are locked out of food subsidies as a result. “The popular narrative around Aadhaar is that it uses technology to provide access to entitlement,” Ramanathan told BuzzFeed News. “But in situations like these, it is actually a loss of entitlement.”

If your fingerprint doesn’t work, you go hungry.

“What evidence does the government have of biometric authentication being appropriate tech for food rations?” asked one Indian journalist who requested anonymity because of their extensive reportage around Aadhaar. “Who is responsible if someone is denied food to which they are legally entitled?”

For years, the Aadhaar project has been challenged by dozens of people — privacy-conscious citizens, ministers, activists, and more — in various courts in the country on grounds of both privacy and exclusion.

Apar Gupta, a New Delhi–based Supreme Court lawyer who represents one of the many litigants challenging Aadhaar, told BuzzFeed News that one of his main concerns about the project is the lack of legislation governing the collection and use of personally identifiable information by Indian government agencies. “If your data is compromised in any way, there is absolutely nowhere that you as a citizen can turn to,” said Gupta. “There are no judicial remedies built into the Aadhaar program in case of identity theft.”

And the Indian government currently appears to have no intention of putting any in place. Last year, government advocates repeatedly told Supreme Court judges that there is “no fundamental right to privacy in India,” in a court case challenging Aadhaar on the grounds of right to privacy.

Historically, attempts to create national identity databases have been met with widespread public resistance and struck down in other countries on privacy and surveillance grounds. In the United Kingdom, for example, citizens' groups and privacy advocates were able to successfully dismantle a similar program in 2010 that would issue every UK citizen a unique number linked to biometric information.

That’s a stark contrast to India, where 22 of the country’s 29 states now have over 90% Aadhaar enrollment, according to a January press release.

“We still haven’t been able to take the conversation around the problems with Aadhaar mainstream,” said Pahwa, who played a key role in rallying public opinion around net neutrality and pushing for the ban on Facebook’s Free Basics program in India last year. “We don’t know how to mainstream this.”

"The reality is that a billion people are using Aadhaar."

Aadhaar’s opponents say the program’s implementation has left India’s poorest people with no choice but to use it. “If you link people’s food subsidies, wages, bank accounts, and other crucial things to Aadhaar, you hit them where it hurts the most,” Ramanathan argued. “You leave them with no choice but to sign up.”

“Can you imagine if the United States passed a law that said that every person who wished to get food stamps would need their fingerprints registered in a government-owned database?” a journalist turned Aadhaar activist who did not wished to be named told BuzzFeed News. “Imagine what a scandal that would be.”

For Nilekani, such criticism is just overstatement and drama. “I think this so-called anti-Aadhaar lobby is really just a small bunch of liberal elites who are in some echo chamber,” he said during a recent interview with Indian business news channel ET Now. “The reality is that a billion people are using Aadhaar. A lot of the accusations are just delusional. Aadhaar is not a system for surveillance. [The critics] live in a bubble and are not connected to reality.”

Abraham laughed off Nilekani’s comments. “The Unique Identification Authority of India will become the monopoly provider of identification and authentication services in India,” he said. “That sounds like a centrally planned communist state to me. I don’t know which left liberal elites he’s talking about.”