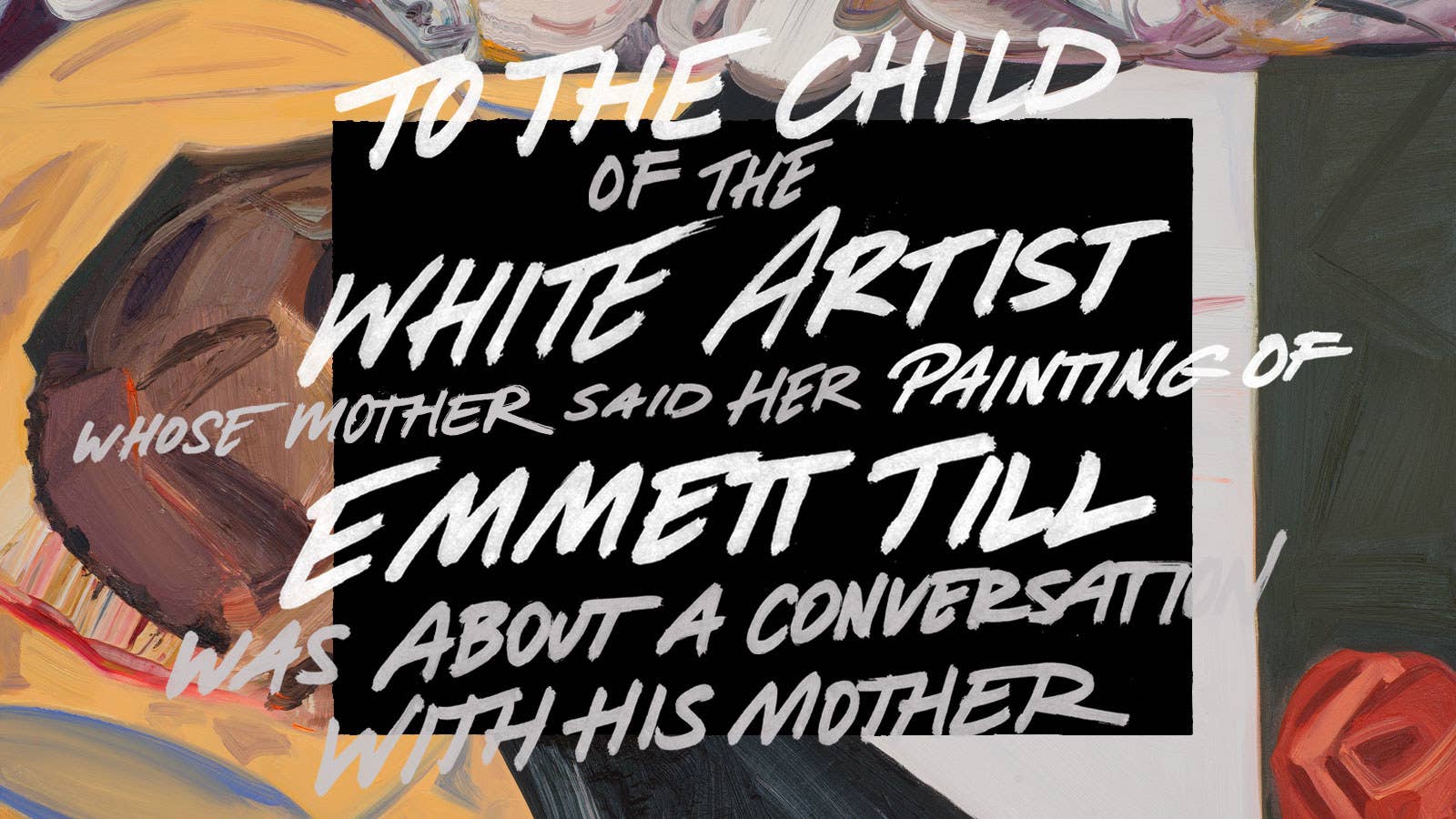

In paint you're still pulling him

out of the river. Still taking the skin

off (again) with a bullet brush. Here is the head

his mother stared at, staring back

at your broken colors. Bruise as palette, as figure.

See, the angle isn't even dead. The day

before America elected 45 I walked through

a vast museum, staring in the pit

of a slave ship. Choking there in the dark,

I couldn't breathe upon those iron shackles

for a baby whose mother might have

held him to her heart as she leapt into the sea.

Don't tell me about a white woman's master-

piece: the tender whistle that lies over black men's

graves. By the time I went to another exhibit

I had to sit down. On a bench in front of Emmett

Till's casket. His mother's voice clear

& strong in a video. A narrative. The black

woman, alive, next to me couldn't stop crying.

A photograph of the boy's face

taped to the museum glass where the body

is there (always). Who would dare

paint it? Pluck the wound into cubes,

globs of cadmium & lashes of umber? What

artist could stand for days in front of

our brother's body? When they write

about destroying the painting, all I

can think of is who must remember

our devastation if not us? A color-

by-number. For millions. The artist says

she'll never sell him the painting

down the river. Imagine what it would take

to paint millions of broken black bones that way?

Does she own us too: the still-life my people

are still dying for?

Forgive me. Is that what your mother meant?

Was it shame or a sensation: this could be mine. My own

child dragged up from ole Dixie's depths? Was it a fear?

Some new art, abstract & apologetic, could be made

in your name, should you walk into a store in 1955

& receive anything but candy? Which can be what

some art insists it is for the artist. We're all talking

about mothers, I guess. It was her imagination

& what is that? Your mother has no intention of selling

it, she says. A black boy's face is free speech

somewhere. Is that what your mother meant?

Or did she slip into another woman's grief with her

brushes & white canvas? Chile, did she tell

you what it meant? When I have to get up in

the godless night & trace that boy's name with a prayer.

Drag his death through burnt syllables until the blood

in me writes & writes & weeps. Did your mother mean

for me to hear Mamie Till's scream in the photograph

she painted? Black woman, monochrome of her

moan above the flower of her son's face? Child,

tell me, what color does your future have? &

what will my unborn children forgive

when they are asked to love you?

Rachel Eliza Griffiths is a poet and visual artist. Her most recent collection of poetry, Lighting the Shadow (Four Way Books 2015), was a finalist for the 2015 Balcones Poetry Prize and the winner of the 2015 Phillis Wheatley Book Award in Poetry. Griffiths' video series P.O.P (Poets on Poetry), a series of intimate interviews with over one hundred contemporary poets, is featured online at the Academy of American Poets. Griffiths' visual and literary work has appeared widely including The New York Times, The Los Angeles Book Review (Voluble), American Poetry Review, BAX 2016/Best American Experimental Writing, Guernica, Callaloo, Lit Hub, Transition, and the National Museum of African American History and Art. A Cave Canem and Kimbilio Fellow, Griffiths has received numerous fellowships including Yaddo, Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center, Millay Colony, and others. Currently, Griffiths is working on her first novel. She lives in Brooklyn, New York. For more information, please visit: www.rachelelizagriffiths.com.