Sometimes I think, Black women are the best of people. Then, before I can correct myself, a Black woman does something that is so incredibly graceful, surprising, loving, disturbing, or fearless that takes the breath out of my chest. What amazes me about my sisters is we’re infinite. We, as poet Walt Whitman wrote (of himself— with the confidence of a white man, no offense to dear Walt, specifically), “contain multitudes.” Contradictions, colors, varieties, inventions. We are growth embodied. We are shape-shifting. The incredible poems below are fly, subtle, wild, soft, cutting. They’ve grown out of the experiences and brilliant minds of poets from Los Angeles, the South, the Bronx, and Salt Lake City, who span multiple decades, sensibilities, histories, futures. I’m in love with the fact that each of them are alive writing now, writing with fierce commitment to language— to poetry— and all of its possibilities.

Look: I almost didn’t write poetry, almost went my whole life hating it. I thought, as many do, that Poetry (capital P), is Robert Frost, William Wordsworth, maybe Emily Dickinson or Sylvia Plath. Poetry wasn’t meant for a regular Black girl. Poetry knew nothing about me, was irrelevant to me. I have never taken a walk in the woods on a snowy evening, and frankly, I don’t care to. I have googled “pasture” and “bougainvillea.” And for a long time, I thought that was Poetry’s job: to make me feel small and dumb, to make me embarrassed about which words and objects make up my life, and which ones don’t.

I love these four poets because they understand that great, impactful, lasting poems don’t close the door to the room, but leave it open. Let these poems be an invitation to never settle for what already exists, to find possibility in every word.

I never met Donald Trump but I sure have been grabbed by the you-know-what & I really don't even want his name in my book & I almost didn't tell this story but sometimes it's important to name names & the luxury of fame is that it doesn't matter what a nobody says if you have enough money you can buy any kind of truth you want when you're a star they let you do it & actually when you're a man in general the one who did that to me wasn't anyone famous it was a homeless man on the La Brea bus I was 15 & had on a white T-shirt & a denim skirt I was with my mother & she tried to protect me but he chased me from the front of the bus to the back & the driver who happened to be really tall & muscular with his uniform sleeves rolled up past his biceps & sunglasses on with a strap he had to stop the bus & push the homeless guy down the exit stairs & he still kept banging on the doors sticking out his tongue & shouting

Khadijah Queen was born near Detroit and raised in Los Angeles. She is the author of five books, most recently I'm So Fine: A List of Famous Men & What I Had On, due out from YesYes Books in March 2017. Her verse play, Non-Sequitur (Litmus Press 2015), won the Leslie Scalapino Award for Innovative Women Performance Writers. The Relationship theater company staged a full production in December 2015 at Theaterlab in New York City. Individual poems and prose appear in Fence, Tin House, Memoir, Gulf Coast, DIAGRAM, Best American Nonrequired Reading, and widely in other journals and anthologies. She is core faculty in poetry and playwriting for the Mile-High MFA program at Regis University. Visit her website: khadijahqueen.com.

Which is to say, on any given day there is a question of origin:

Georgia clay South Carolina piedmont

How many chains before the boat? My name is dust.

When I say generations, there are only 4 & then silence

My blood is bought & sold. At 6 years old, Grandpa

was listed tobacco laborer in the Census. When she broke him,

Grandma brought him to the suburbs, & he turned his acre plot over

& over to seed & chicken feed & rabbit pellets. Daddy’s father

fought in all the great wars, survived, only to drown

his heart in bourbon. No one has survived grief long enough

to live past 80. I wake in the middle of the night

to check my pulse, wonder how long after your heart stops

you keep living, or is it sudden gone? Grief

is a volley ball lodged behind my shoulder blades. Am I gone?

In 22 days I will mark another year: both the last day Grandma lived

on this earth, & the last time I heard my Mama’s voice.

Looking into our eyes that first month, that third month,

Doctors said it’s possible to learn to talk again. Then the ninth month

came & they stopped coming around. How long Mama will survive

this silent grief? My capacity to make it 1 year

without my mother’s voice is dwindling. Last night

my pulse read 90 bpm. 84 bpm. At 3:45am it read 95,

then back down to 80. At 157 bpm, I enter tachycardia.

Once, at 5, I lived. But the blood lineage: diabetes, diabetes,

congestive heart failure, stroke, diabetes, stroke, lung cancer,

congestive heart failure, liver cancer. At 36, my aunt

at the front of the classroom slumped over & died. At 32, I wonder

what living I need to do in 4 years if these are my last.

DéLana R.A. Dameron’s second collection of poems Weary Kingdom is forthcoming from University of South Carolina Press in April 2017, as part of the Palmetto Poetry Series. Dameron’s debut collection How God Ends Us was selected by Elizabeth Alexander for the 2008 South Carolina Poetry Book Prize. She has conducted readings, workshops and lectures all across the United States, Central America and Europe. DéLana holds a Master of Fine Arts in Poetry from New York University and a Bachelor of Arts in History from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. An arts & culture administrator, Dameron is a native of Columbia, South Carolina, but currently calls Brooklyn home.

So notorious you don't even know what I look like

everybody's boo everybody first love everybody's thot everybody good fuck everybody's tit everybody's mama everybody's abandoned everybody's excuse everybody's lament You love

that shit, the way I put my black on

flex in it, put my whole foot in it, so black you can't divorce it, so black you don't speak

my language, black in your wet dream, I come

Black. My black is residual, will not wash out of the duvet.

you love to deliver

love to send the sickled train down my throat, love to shut me up

turn the floodlights off &

Trap Queen don't fear shit except, how easily

my body leaves me, how often it is not mine.

Trap Queen don't fear shit, except an unlimited

caricature, except the way they tow my narrative

right out of my own mouth and iron it out flat.

Trap Queen don’t fear shit, except for how

Errybody lay claim when the sun falls, except

for how I can't keep a moment of myself to

myself. Don’t fear shit except the way my

lonesome is your invitation, the way

all my power coagulates

The way the world will lay its violences at the threat

of my able black body. Except, the way nobody

got my back. Until I’m face forward, an obituary

a red prayer orbiting, until

Errybody forget about it

& find my sister. & Repeat.

Camonghne Felix is a poet, political strategist, media junkie, cultural worker & NYC native. She received an M.A. in Arts Politics from NYU, an MFA from Bard College, and has received Fellowships from Cave Canem, Callaloo and Poets House. The 2012 Pushcart Prize nominee is the author of the chapbook Yolk, and was recently listed by Black Youth Project as a "Black Girl From the Future You Should Know." Her first full-length collection of poems, Build Yourself a Boat, is a University of Wisconsin Press Brittingham & Pollak Prize finalist.

Clouds hanging so low they almost touch

the wooden colonnettes of the big house

the brick, held together by animal

fur and mud, bousillage, the hands

that formed it. I raise my arm and rub

the belly of a cloud

our tour guide is Black and doesn’t remark

on architectural flourishes. I am grateful

and still wiping sweat from my brow

We are in Wallace, Louisiana

looking for our people’s names

now upon a marble wall of 70,000

first names in no particular order

I sidestep a white man with a camera

so that I can take my mother’s

hand from her mouth and hold it

On the way to New Orleans we stop

to gather Spanish moss

a groundsman opens the gate after hours

he looks softly after my mother and me

could it be that he is one of us

I fill my purse with moss and unlock

the rental car

How cruel the sun must’ve been

to the slave, I think, when I get back

to our French Quarter hotel and lay

poolside in a two-piece

desperate, almost

Rio Cortez is a Pushcart-nominated poet, who has received fellowships from Poet's House, Cave Canem and Canto Mundo Foundations. She was a recipient of the Sarah Lawrence College Lucy Grealy Prize in Poetry, the 2012 Poets & Writers Amy Award, and a 2015 Jerome Foundation Grantee. She is a graduate of the MFA program at NYU and co-founder of the Good Times Collective and BLKGRP. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in a number of journals, including The Miami Rail, The Offing, Cortland Review, Prairie Schooner, and Huizache and The New Yorker. Rio Cortez has been selected by Ross Gay as the inaugural winner of the Toi Derricotte & Cornelius Eady Chapbook Prize for her manuscript, I Have Learned to Define a Field as a Space Between Mountains, available from Jai-Alai Books. Born and raised in Salt Lake City, she now lives, writes, and works in book publishing in NYC.

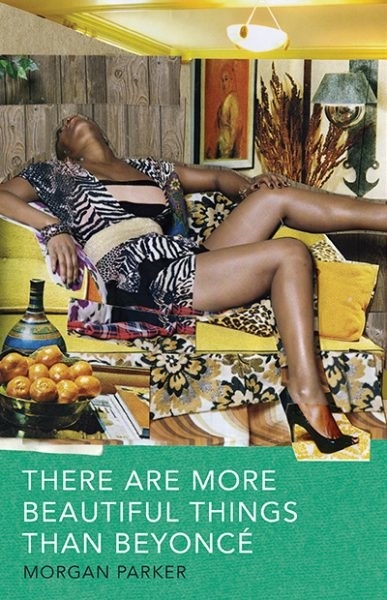

Morgan Parker is the author of There Are More Beautiful Things Than Beyoncé (Tin House Books, February 2017) and Other People’s Comfort Keeps Me Up At Night (Switchback Books 2015), selected by Eileen Myles for the 2013 Gatewood Prize. Morgan’s work has been featured or is forthcoming in numerous publications, as well as anthologized in Why I Am Not A Painter (Argos Books), The BreakBeat Poets: New American Poetry in the Age of Hip-Hop (Haymarket Books), and Best American Poetry 2016. Winner of a 2016 Pushcart Prize and a Cave Canem graduate fellow, Morgan lives with her dog Braeburn in Brooklyn, NY. She works as an editor for Little A and Day One, co-curates the Poets With Attitude (PWA) reading series with Tommy Pico, and with poet and performer Angel Nafis, she is The Other Black Girl Collective. www.morgan-parker.com