It’s safe to say that the career of Alessia Glaviano — the brand visual director of Vogue Italia and director of Photo Vogue — has centered around shaping the modern photography industry. This year marks the 10th anniversary of Photo Vogue and Glaviano’s 20th anniversary at Vogue Italia — big milestones for a woman who used to buy copies of the magazine at a corner store in New York every month. We may associate models in bright clothes with fashion photography, but images that are thought-provoking, discomforting, and inquisitive are what compelled Glaviano toward the field.

We asked her about the photographers and images that influence her. She said that two things interest her: people, and what we can do to help them. “I like images that restore that complexity. My passion is to discover new things, to be able to change my mind about something,” she told BuzzFeed News.

Here are just a few of the photographers and works that inspire Glaviano. This list has been condensed and edited.

Marco Glaviano, “Ashley and the Tree,” circa 1980s

“This is from the 1980s, it was photographed in St. Barts. My father’s work was my first aesthetic influence. It was not always an easy father-and-daughter relationship, but he introduced me to the world of art and fashion. When I was a child, he used to work for Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. He lived in New York at the time, and I would go hang out on sets. This was a seed of what made me so passionate about photography. I’m also more aware now of certain biases I have. If I think back, most of the artists who influenced me are Western artists.”

James Nachtwey, “Nicaragua, San Juan del Norte,” 1984

“In my opinion, he is one of the most powerful photojournalists from the last century because of his ability to frame and compose images, even in such conditions, the care and attention that he dedicates to his photographs is the same care and attention he has to his subjects and the causes he denounces. The first thing that comes to my mind by looking at this image is the very strong reference to [Andrea Mantegna’s 'Lamentation of Christ']. I don’t even think that reference is conscious, but to look at the image and see the death of Christ, it’s already a photograph that makes you think. We are complex, full of contradictions; this complexity is something that is not accepted in our contemporary world.

“All of the issues that we need to reflect on when we speak about images of suffering, images of war, Susie Linfield wrote about in her book The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence, a must-read for people who are concerned with the history of photo criticism. Why do we judge the morality of the photographer more than what the picture is showing us? Can an image be at the same time horrible and beautiful?”

Sebastiano Tomada Piccolomini, Photo Vogue, 2011

“This image was taken by Tomada in Afghanistan, and I published it in Photo Vogue in 2011. I had just opened up Photo Vogue, a platform I curate and direct. I published this image as the picture of the day, and the late Franca Sozzani, who was the editor-in-chief of Vogue Italia at the time, called me and said, ‘Alessia, what are you doing publishing images of war?’ But I fought for it. I said that I didn’t want this platform to just be for fashion photography. Of course, it’s Vogue, but Vogue is a brand, and I feel that we should be talking about everything. I stood up for something I believed in, and we kept it. Today, Photo Vogue has submissions from more than 240,000 photographers from all over the world, and we speak about so many different issues.”

Jeff Wall, “Picture for Women,” 1979

“This image is the epitome of one of the things I love the most about art: when there is meaning but also strong, powerful aesthetics at the same time, when images are powerful and immediate from an aesthetic point of view so that they are accessible to everyone. I don’t want to take two hours just to speak about this, but the camera in the middle, the woman looking at us, the photographer — there are so many concepts in this image. You can be struck by the beauty of this image and the fact that you don’t really understand it. Is there a mirror? What’s going on? The picture lends itself to several readings and interpretations. It speaks about the representation of women but also challenges our capacity of observation and questions the role of photography as a witness of reality. All of this is condensed in just one image.”

Nan Goldin, “Rise and Monty Kissing, NYC,” 1980

“She is an incredible artist. I think what she did for photography was immense. She had an influence on so many generations and so many other incredible artists after her. She started, if you like, a social media approach to photography before anyone else, before even social media. She started a documentary, diaristic approach. Nan was photographing her community. This image is from The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, which was an achievement of the arts in the 1980s. The idea of this community of friends, all nonconforming people, and capturing intimate moments with this extended family and moments of love and loss. People like Wolfgang Tillmans, Corinne Day, and Ryan McGinley, they all come from there. She also worked in fashion. She loved fashion. Her work really, really touched me when I was a teenager, so she has a particular place in my heart.”

Diane Arbus, “A Family on Their Lawn One Sunday in Westchester, NY,” 1968

“We’re speaking about incredible artists — all these people are changing the medium of photography or introducing new languages. Arbus started photographing the unfamiliar. It’s interesting to think about how we would judge her if had she lived and were photographing this today. The reception would be different, of course, and luckily these days we are more aware and respectful, but these images need to be contextualized; you can’t judge an artist of the past or their art with the awareness of today. When she started to do this, it was amazing that someone would turn their camera to show us these uncommon and uncomfortable scenarios and people. She didn’t want to reform life; she wanted to understand it. It’s about compassion and sympathy for the imperfections. The fact that she killed herself in 1971, she was herself someone who was suffering. Her ability to show us the unfamiliar and not to judge, her images are never judgmental. She has been an incredible inspiration.”

Philip-Lorca diCorcia, W magazine, 2000

“This image is for a story for W magazine in 2000. It’s a reference to Edward Hopper. I am a big believer that fashion is a language and speaks about identity. When you take a fashion picture, you can go buy the clothes ‘advertised’ in it for six months — but after that, the image becomes a document. There are so many incredible images. If you think of Richard Avedon or Irving Penn, they started in the pages of a magazine, and today they are on the walls of museums. DiCorcia is someone I’ve looked at a lot. The theatrical representation of reality in photography, images that are never didactic or rhetoric — and by looking in and looking more, you understand that there are other things at play in the images.”

Francesca Woodman, “Untitled, MacDowell Colony, Peterborouogh, New Hampshire,” 1980

“Her work touched me a lot. The way she was taking pictures of herself and blending in with what she was photographing — the walls of the room, nature, the trees. The idea of disappearing and blending in, the idea of fragility and of exposing oneself, it’s the female gaze before the female gaze. If you think of how much she is loved, it’s because her work is so authentic, and that is why we still respond to it so strongly.”

Gregory Crewdson, “Untitled (Robin With Ring of Eggs),” 1992–1997

“Crewdson is a friend. I remember going to see an exhibit of this series in New York in the ’90s. The work was inspired by the dioramas in the natural history museums. If you look, you will see already all the themes he will explore in his career. I love this image. I love this entire series. I love his approach to mystery and the uncanny. It’s very clever how he can speak about the uneasiness of life, the so-called suburban normalcy in America, how mysterious it can become. It makes me think of Close Encounters of the Third Kind. I prefer the still image to the videos. It’s more interesting. It’s open-ended. Photographs that are about the moment of transition between before and after — but you don’t really know what happened before and after, you are filling in the story with your imagination. That’s something that he believes in, and I do too.”

Thomas Hoepker, 2001

“We all know there is a world before and a world after 9/11. I had just moved back to Milan after many years in New York. I had only been gone two months to take the job at Vogue Italia. I think this image is a metaphor for the surreality of what happened. It was so heavy when we all witnessed it on TV. It was so surreal how incredible and ambiguous and confusing it was. This is all in this image, which is not at all that these people are there and they don’t care what’s happening on the other side of the bridge. This is just a frame, a moment in time. Images aren’t always the truth, and we don’t know what they were saying, how they felt.”

Ryan McGinley

“I think that there is a before and an after Ryan McGinley in fashion photography. He was able to create this work that didn’t exist before. Again, he was documenting his friends, but he was living in the East Village and surrounded by super-cool people like Dan Collin and Dash Snow. He brought a joyful documentary style to his photography — the idea of freedom, a celebration of life, being in nature, and even the way that he treated gay male bonding in a refreshing, direct, immediate, and autobiographical way without being narcissistic.”

Kenneth Josephson, “Polapan,” 1973

“Josephson made me understand the importance of referencing other work. At times, it’s hard to know who started something. It’s like Guy Bourdin — they both used illusions to draw your attention to the artifice of the picture, the picture itself being an object. He was an intellectual about photography, and this image reminds me also of the concept that the map is not a territory. That means individuals don’t have absolute knowledge of reality. You look at things with a model you have in your mind as how it should be, but when you go out and see the places, that is real, not the map. Representation is representation, it’s not reality. ‘Ceci n’est pas une pipe.’”

Bruce Davidson, “Brooklyn Gang,” 1959

“This is another example of how you can’t really label things and divide them. You look at his series Brooklyn Gang… These could all be fashion images. There are so many documentary photographers that I admire like Davidson. Danny Lyon, for one. They were documenting their communities, what was going on, where they were living. The people they photographed had such great style; they could just as easily be fashion images. It’s important not to label, to be open, to look at what you have in front of you without judging.”

Steven Meisel, Vogue Italia, 1998

“I lived in New York when this cover came out, and I would buy Vogue Italia every month. It was my dream job. I loved it so much. It had everything — strong aesthetics and important concepts, and most of that was through the lens of Meisel. I chose this particular image, but it could have been any other cover from the ’90s. It references ‘Relation in Space,’ a 1976 performance by Marina Abramovic and Ulay. Meisel is my favorite fashion photographer of all time. He wrote many chapters of the history of Vogue Italia, and he is more capable than any other of overturning conventions, breaking rules, and using fashion as a lens to talk about so many other things, from the obsession with plastic surgery to oil spills to mental health. Voracious in terms of his influences, he looks at everything, absorbs everything, and does it better and in his unique way without ever plagiarizing. He has been a huge influence on my aesthetics.”

Maisie Cousins, “Peony,” 2016

“This is part of the Female Gaze exhibition from the first edition of the Photo Vogue Festival in 2016. I proudly call it the first conscious fashion photography festival, which works at the intersection of ethics and aesthetics, because this has been my mission since day one.

“My awareness of what was happening with the female gaze started when I interviewed Bettina Rheims, a great friend and incredible artist. For over 30 years, Rheims has produced work that explores and investigates the female body, identity, and gender issues. She made me think about taking back the male gaze and photographing women in a way usually done by men. Women are always being asked to conform to that and take upon themselves the same objectifying point of view.

“This was the beginning of an awareness that brought me to identify all the contemporary young women who are using photography in this sense, who shifted their lens onto other young women producing nonstereotyped images with a strong erotic component that are a manifesto of sexual emancipation and reappropriation of one’s body. A body that is real, authentic, and portrayed with all its signs and imperfections that are no longer seen as ‘mistakes’ to be retouched. Finally, we arrive at a more sincere and truthful representation of women. I think it’s the most important thing that has happened to photography in the past 10 years.”

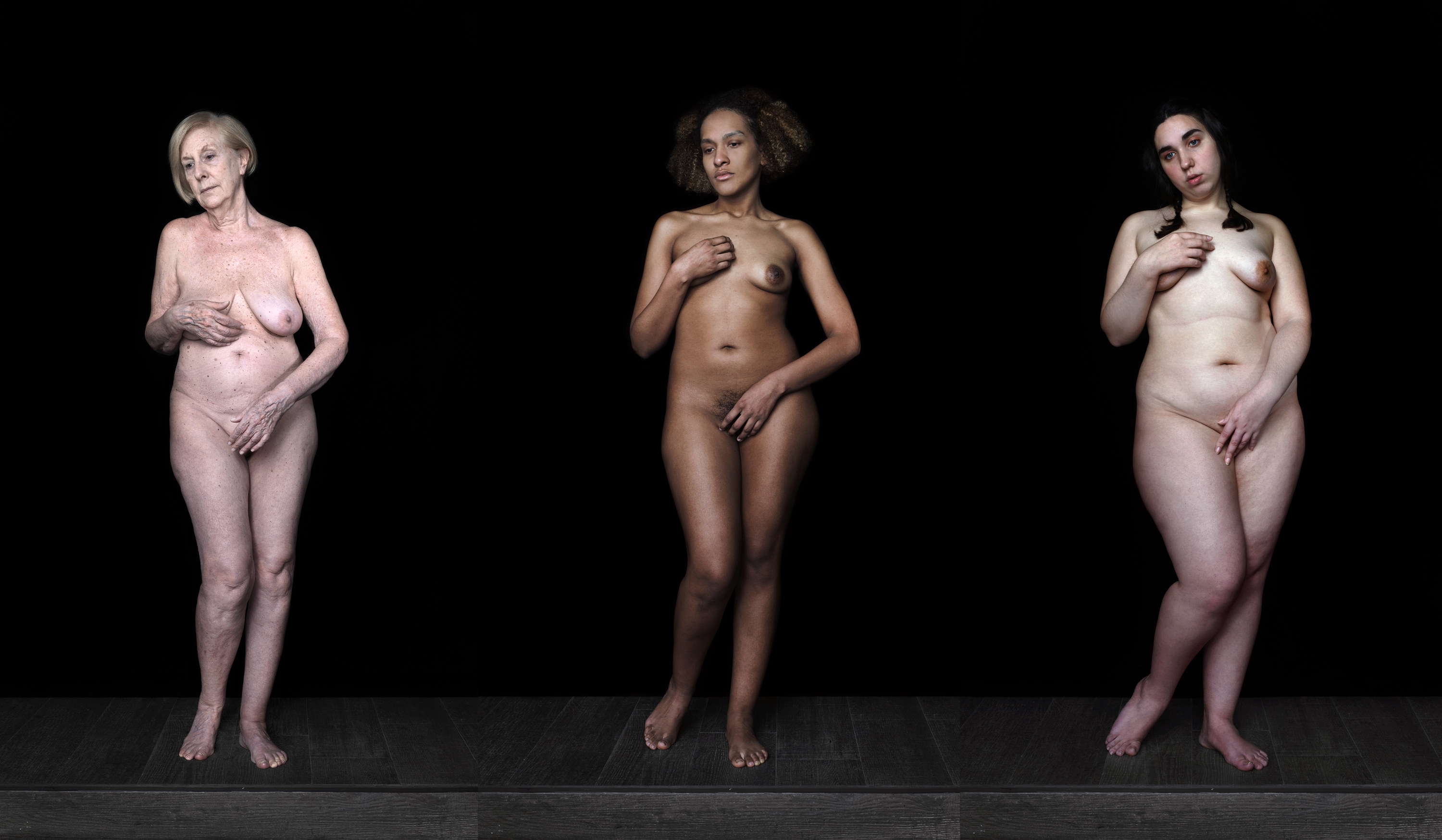

Romina Ressia, 2019

“This image was in the exhibition A Glitch in the System at Photo Vogue festival in 2019. It is a symbol of many of my battles regarding representation. The idea of diversity, there are different kinds of bodies and different beauties. Romina photographed many different women referencing Botticelli’s ‘Venus.’ A Glitch in the System is a continuation of what we started the year before with the exhibition Embracing Diversity, we wanted to explore and promote diversity in all its forms by taking a step further, by extending the concept to include not only the subjects whose stories are being portrayed but also those behind the camera who tell those stories, on how we choose to represent diversity, so as to avoid perpetrating clichés and reinforcing an ideological vision.”

David PD Hyde, “Ellie”

“Ellie Goldstein is a model with Down syndrome, and she was the protagonist of a digital story that we produced for Gucci Beauty with Hyde, a super-talented photographer from Photo Vogue whom I really like. He also has a disability.

“If there’s one thing I’m proud of, it’s the work I've done toward the representation of people with disabilities. I always thought about how kids must feel — growing up and never seeing yourself. Not in an advertisement, not in movies. There’s a complete lack of people with disability representation — or, when it’s done, it mostly falls into the trap of presenting their subjects as brave, pitiable, or some mix of the two.

“This image is a symbol of my commitment. It went viral, the image and the story, and Ellie is now a model who works a lot. I am so happy about this. If there’s one thing I’m very proud of and I want to keep doing, it’s work like this.”

Alexandra von Fuerst, Nadine Ijewere, Ruth Ossai, and Camila Falquez

“In this year’s Photo Vogue Festival, we did two exhibitions: One was called All in This Together, and the other one was called In the Picture, with four young artists, whom I really, really love. The artists were Nadine Ijewere, Ruth Ossai, Camila Falquez, and Alexandra von Fuerst. Going back to the idea that every image is political, we wanted to explore what this means when we speak about fashion. I think that these four artists are contemporary socially conscious fashion photographers. Their work is imbued with issues of gender, race, and womanhood, without ever being didactic or redundant. It’s instead very glamorous, vibrant, and powerful.

“They are four artists working in an industry — fashion — that is undergoing a profound journey of self-reflection, and they are not mere bystanders observing the change but rather part of the main driving force.

“I think Ruth’s work is extremely important. As she says, when she grew up she thought that fashion photography was inaccessible and untouchable. In her words, it can also be the everyday and imperfect, while filling her subjects with power and agency. It’s not that fashion has to be for a certain type of person, class, or demographic.”