As queer men were ostracized from society in the early 20th century, some came together to form a community on a secluded strip of beach just off the coast of Long Island. One such community was Cherry Grove, which is the subject of an exhibition at the New-York Historical Society titled Safe/Haven: Gay Life in 1950s Cherry Grove. As the area evolved over the years, one man made it his mission to save artifacts from this community, eventually forming the Cherry Grove Archives Collection. What began in the 1940s as a simple collection of photos has become a treasure chest of queer history that includes house signs, playbills, and films that show the daily life and fabulous events of the Grove.

“Harold Seeley lovingly collected all this material from our community that he thought would one day be valuable," said Parker Sargent, a documentarian who has made several films about Cherry Grove and helped curate the exhibition. "He didn't really do much with them in the way of preservation; he was more of a collector. But when he died, he chose a group of people to continue his work. And since then we've been trying to catalog and digitize everything he collected.” The Cherry Grove Archives Collection has held a large film festival for three years to help cover the high costs of digitizing all the material. BuzzFeed News spoke with Sargent over the phone about why this collection is important. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

What was it like to look at these photos for the first time?

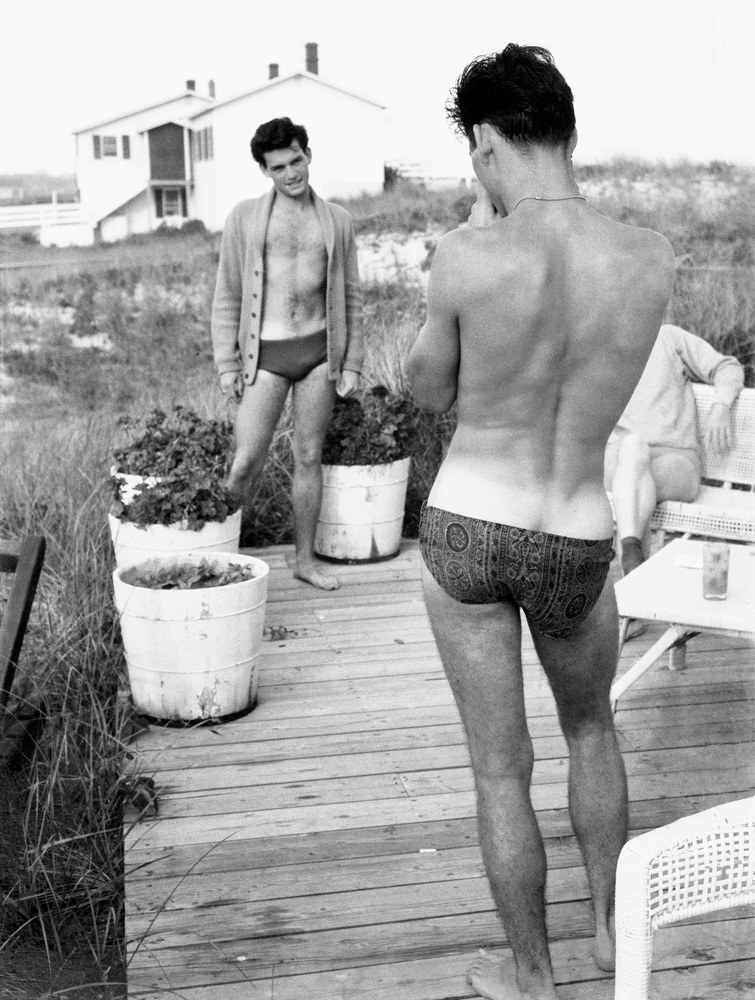

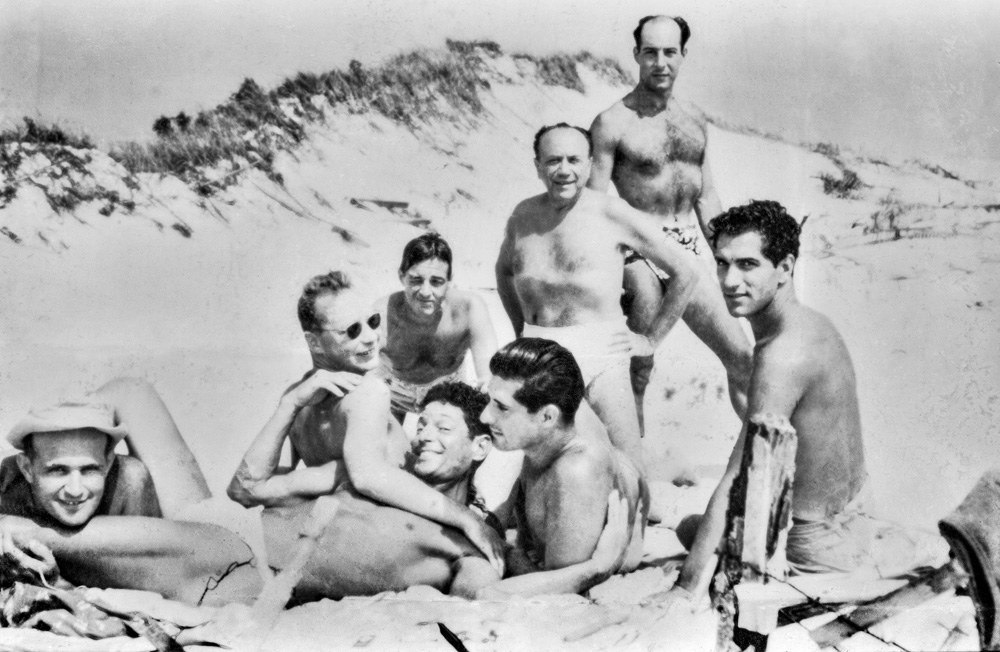

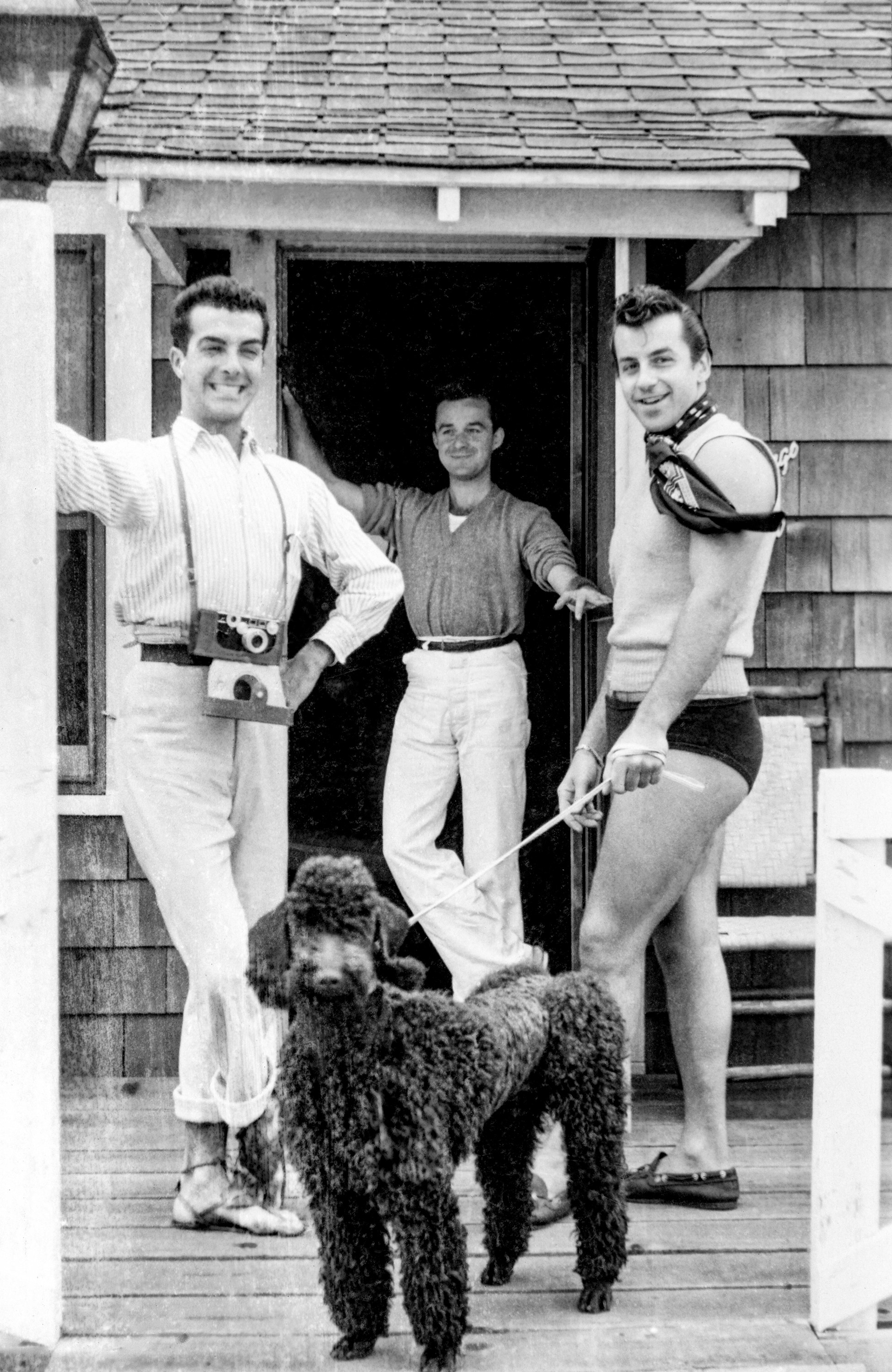

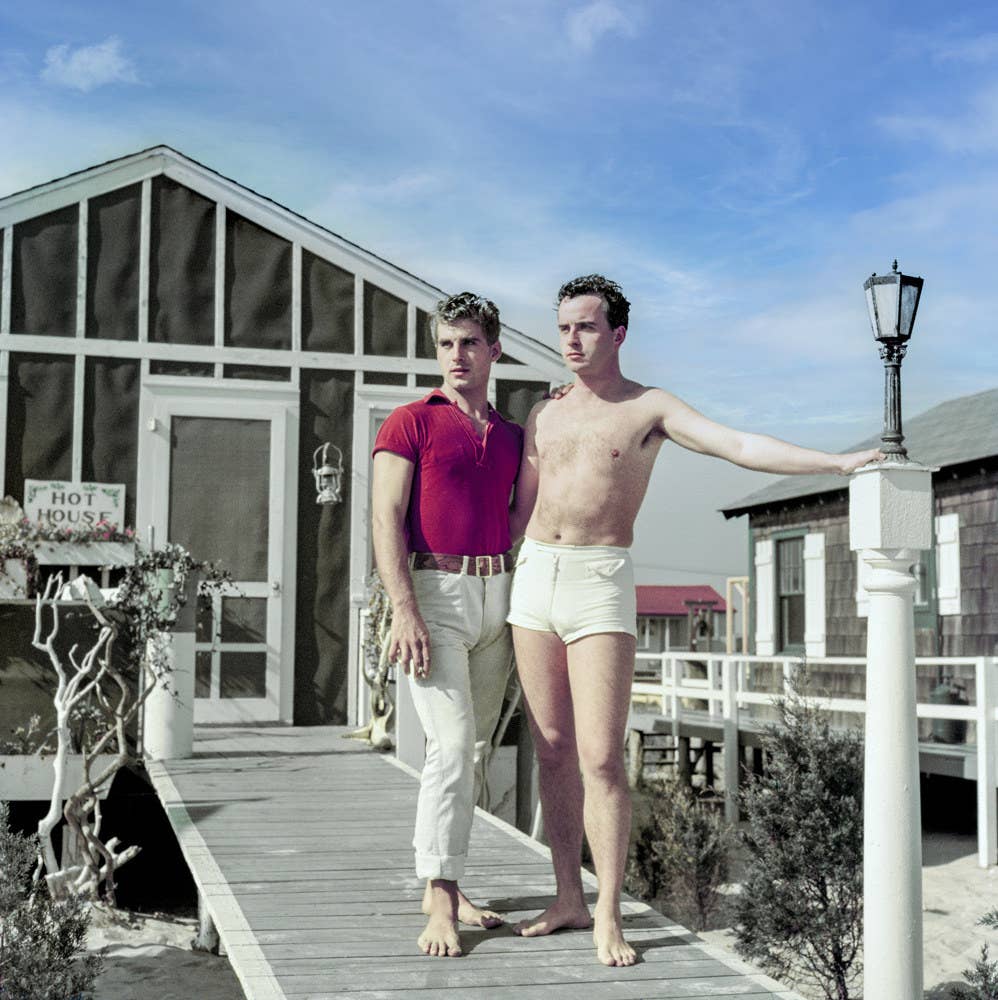

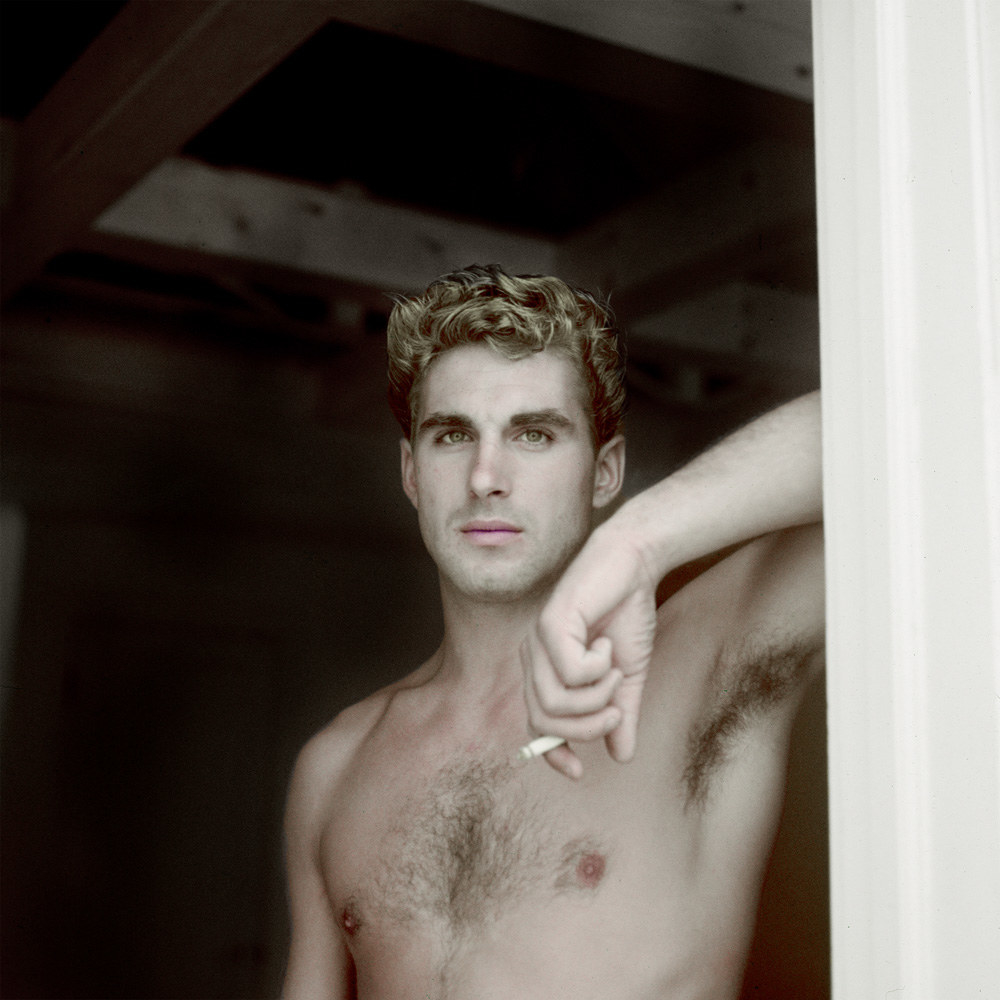

When we started scanning images from the 1950s, we were immediately blown away by joy. I felt like, oh my god, I'm looking into the faces of people I know today. As a trans woman, I definitely felt like I was not present in Cherry Grove at that time, but gay men and women were there, carving out space that I get to inhabit today. There's this idea that before Stonewall, everyone was repressed. This is the time of the McCarthy era and the Lavender Scare, when men couldn't dance with men, women can't dance with women. And queer people were not allowed to congregate. It's easy for us as a newer generation to think they must have just been living in hell — but to look back at these photos, the people in them are happy. They are joyous.

Let’s be honest, we are looking at predominantly white men, because that's the unfortunate truth of the world, that white men get everything first. They may not have been highly affluent, but they had enough income to rent these basic little cabins out on Cherry Grove. The longtime residents, who were mostly straight families from Long Island, used Cherry Grove as a fishing spot and for the amazing beach.

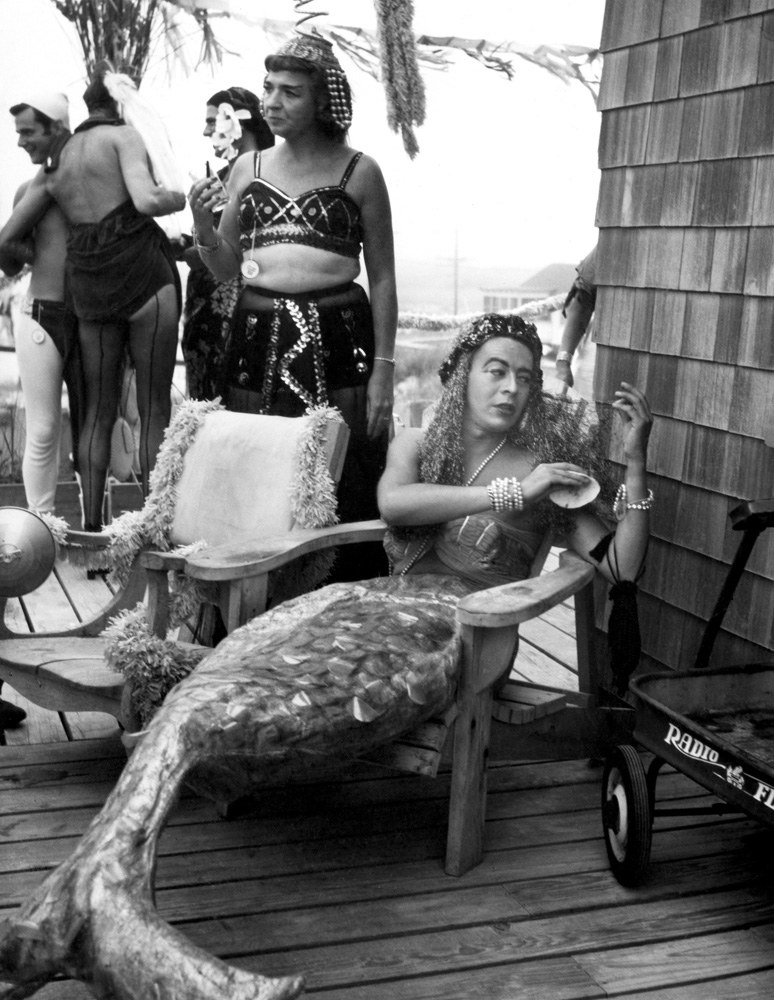

Gay men and women working in New York City as costumers, directors, actors, and dancers were referred to as the “theater people” by locals. Soon these “theater people” would start to formulate a strong community where people were able to be openly gay; they could cross-dress and play with gender norms.

What makes these photos so wonderful is that they are very rare. In the 1950s, it was dangerous for queer people to document themselves. Simply having photos developed that reflected homosexuality could get you arrested. We have a lot of lost history that was thrown away, so these photos from the archives add so much to our knowledge of what gay life was like. It's really wonderful.

What makes the Cherry Grove community so unique?

We have 300 houses out here. Of the 15 other communities on Fire Island, most of them are straight. Lots of families. There is a transient community in Cherry Grove, people who just come for the day to enjoy the beach and the bars. There are a lot of people who rent [a house] for one week or a month. But these people, they still consider themselves “Grovers.” It's such a special place of celebration and healing. The beach is incredible. The people are friendly, and we have always been on the front of LGBTQ+ rights and fighting for freedom to be out and proud.

Back in the 1950s, there was no running water and no electricity, but gay men and women were happy to be roughing it because they were free to be themselves. If you were gay in the city, you went to these dark and dingy bars, which were run by the Mafia, and at any time it could be raided by the police and you could be arrested.

Out in Cherry Grove, the police would leave on the last ferry to the mainland at midnight, allowing same-sex dancing and open expressions of affection to occur in the local bars and restaurants. It truly was a safe haven for so many people, which would only increase over the following decades.

For instance, the tradition of the Invasion of the Pines is a well-known 4th of July event on Long Island with roots in activism. In 1976, a trans woman named Teri Warren was refused service at a restaurant in our neighboring community, the Pines, because she was in drag. A group of friends led by Thom Hansen (known to the community as Panzi) stormed the Pines in full drag and demanded service to show their support for Warren. Each year, thousands of people come together to dress up and celebrate Independence Day in the gayest way possible … with hundreds of drag queens on a ferry returning to the Pines to keep the tradition going. That could only happen in Cherry Grove. And we, like the rest of the world, are looking to make our community a more inclusive place for people that still need a safe haven.

What do Cherry Grove and other predominantly queer spaces mean today in a more open and progressive country?

So many people don't think that you need a queer space anymore, but I definitely think that women, trans people, and people of color still need this space. We need Cherry Grove. My wife and I came to the Grove simply to find a safe place to wear bikinis on the beach as trans women and not be in danger of intolerance — and I have to say, it is the safest I’ve ever felt in any space. Maybe rich white men don’t need this safe space anymore, but it’s vital for so many other queer people.

How large is the archive?

In all honesty, we still don't know how big the archive is, because we are working hard to digitize material, and our community is always donating their photos and artifacts of their life in Cherry Grove, trusting us to preserve their history.

A lot of things we have, Harold Seeley literally found in the trash. When community members in Cherry Grove would pass away, their straight family members would clean out their houses to sell because they did not want to live in a “gay town.” A lot of our community died of AIDS, and their families would come out here and want to sell their homes. People were afraid of AIDS. They didn't want to be here. These family members often threw out any evidence of their gay uncles or cousins. Seeley made it his mission to save these treasures.

It's really expensive to have things digitized, and our work is funded by our community’s generous donations, so we put a lot of time and effort into fundraising. It’s challenging and time-consuming, but we all feel really lucky that we have this adventure ahead of us.

How did the exhibit at the New-York Historical Society come about?

When we saw these photos from Seeley's collection, we saw that it was adding something to the lexicon of gay life. Whenever people show something in a documentary or in a book, most of the photos of gay life start at Stonewall and goes on from there. We saw that we had this new element to add, these photos that people had not seen before.

The three cocurators, Brian Clark and Susan Kravitz [and myself], we're all friends who work together as volunteers, and we spend so much of our time together. So when we embarked on this adventure with the New-York Historical Society and Rebecca Klassen, they helped us take our exhibit and make it even more [special]. We feel lucky that the NYHS saw the value in gay history, because not everyone does.

At the Stonewall Museum, most of the patrons are queer. But at the NYHS, it will be seen by people of different sexes, nationalities, and sexual persuasions. We hope that everyone can see aspects of themselves and their own journeys through understanding the struggles and triumphs of our queer community.