Serbest Salih’s traveling darkroom is unlike almost any other in the world — a few miles over the Syrian border in Turkey, it moves on a trailer hitch like a caravan from town to town. The darkroom works primarily with children, most of them refugees like Salih himself.

“I'm from a town on the Syrian border,” Salih said. “After ISIS attacked, I came to Turkey and started working with NGOs as a photographer. I was introduced to the Sirkhane social circus school, which works with children. Through them we created the Sirkhane Darkroom, a mobile photography project for refugee and local children, which works with analog photography.”

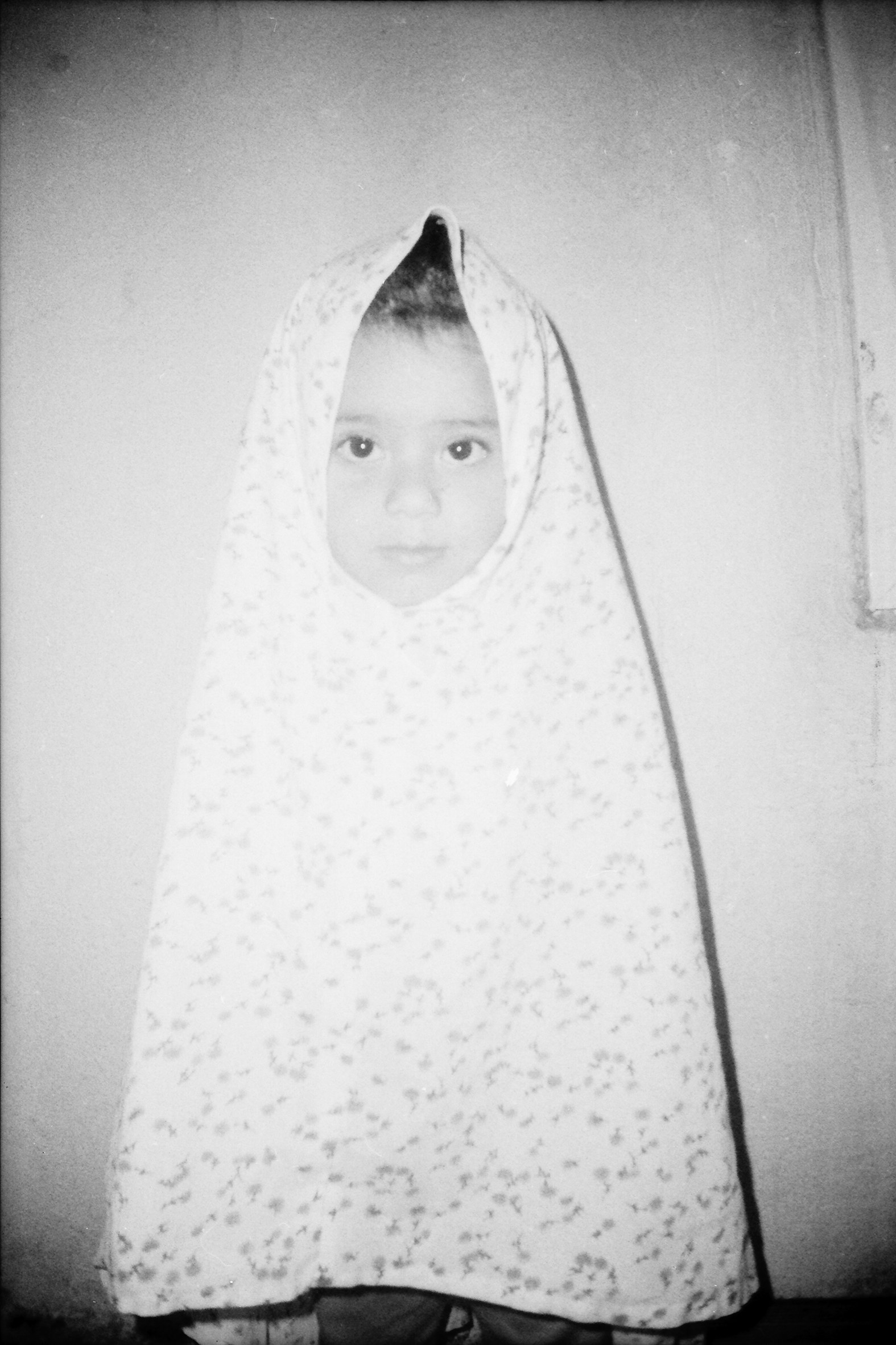

The darkroom works with children from communities all over Turkey, starting from Mardin and Istasyon near the Turkish–Syrian border. The traveling container studio functions as a classroom. The kids select the subject by themselves, but Salih said that the photography focuses on the more joyous and playful moments of their lives.

For the children and families on the border, the displacement and refugee experience has been a taxing and constant reality of the last decade. With Mack Books, the darkroom took input from students in the program when curating a collection of their photographs for the book i saw the air fly, out this fall.

What was your introduction to photography?

I started photographing in 2012, when the Syrian crisis was getting bigger. There were a lot of displaced people from city to city, coming to Aleppo. Once I saw people's portraits and faces, I was inspired to photograph them. I registered in the photography department at Aleppo University, and I graduated in 2014. After I graduated, I came to Kobani, and after that I came to Turkey.

How did the darkroom start?

I run the project by myself, under Sirkhane, a social circus school and nonprofit. In the beginning of the project, my friend and I created it together with funding from an NGO. After 10 months of support, the funding ended, so we did fundraising to continue the project.

I'm hoping to use the mobile program to reach more children — it is a very useful tool and lets families know more about the workshops. They think that photography is too hard for children. They want to send the kids away to have a little bit of time alone. But after they see the results of the workshops and the communication, they take it seriously.

During COVID-19, we received support from an NGO, Welthungerhilfe, who sent us internet, but most kids didn't have a smartphone, so they mostly weren’t able to access online workshops. We just started holding workshops face-to-face again, and the kids are really excited.

What are some of the themes that the kids photograph, once you give them cameras?

I'm always surprised by the kids with this project. You see different sides of the children and new things every time. People are always asking me, What are the effects of children affected by war, or refugee children? But it's always about happiness. They don't share moments of sadness with us, it's always about playing with their friends and about happiness.

What’s something that consistently surprised you about this work?

First, adults tend to think that children will not take a good photo. The kids are very small, they use very simple cameras. They share their world, their private moments in their homes when they're having lunch or breakfast, when they are playing inside or outside the home. It's about happiness. They are playing with shadow, light, and enjoying themselves. The darkroom isn’t their only art education. There's a lot of other classes, but when you are not going to school, you don't have access to a lot of things, like integrating with children.

What were your hopes in starting this project?

For the children in the future, I hope that art will continue to be a very good tool to empower them. You can see it after they participate in our workshops, they improve and they start expressing themselves. I'm always telling them that they can continue this after the workshop, that they can use their smartphones to take pictures. Sometimes I talk to kids who took the workshop three years ago, and they are still taking pictures.

We want to use photography as a language to integrate all the communities in the area. There may be in a village Arabs, Kurds, Iraqis, Syrians, Kurds from Turkey, Kurds from Syria. We want to let them use photography as a language to express themselves and bring this community together. With digital, they can delete photos directly, if they don't have the self-confidence or if they think that it's bad. With analog photography, they can't see the photos. The children have to come to the workshops, develop, print, and see all their results. They get self-confidence and start believing in themselves throughout this process.

Maybe a previous student will take over or continue this project. My goal is not to have to search for funding; funding is really important. My goal is to find people to donate secondhand cameras, and that kind of thing.