Since 9/11, Peter van Agtmael has photographed in both the US and the countries that the US has been at war with. His new book, Sorry for the War, interrogates and implicates politicians and regular Americans in the violence and warfare that have torn up the Middle East for the past 20 years.

He has been interested in covering war since he was young, but how he interacts with it through photography has changed immensely over the past 15 years. Both his grandfather and his father had military experience, and he grew up with those stories in the family lore. “I have no immediate plans to return to the region,” he says. “But everything I do moving forward until the day I die is going to have something to do with 9/11 and these wars and their impact and consequences in the world. They’ll always be a direct part of my life.” The book encourages Americans to see the absurdity and the serious consequences of wars that we are implicitly involved in but often opt not to see or engage with.

What led you to this kind of photography — to focus on war, conflict, and the ugliness of American expansion?

Little boys in America often have a keen interest in war. Society encourages you to pay homage to the triumphs of America’s martial glory. Broad parts of politics, pop culture, and Hollywood fetishize physical courage and the eternal battle between “good and evil.” When I was younger, these simplistic ideas were very compelling to me. Beyond the drumbeat of society, there was a proud family history in the military, and I believe something primal in me as well. To top it all off, I was very socially marginalized for years of my adolescence, and these grand ideals seemed like a shortcut to masculinity and status. Quite dark and immature reasons to want to go to war, but surprisingly commonplace, which is why I try to be honest about my failings and foolishness. I see the power of those same seductions present in many others, often wrapped in a veneer of patriotism.

When I was in college, I developed a strong interest in journalism, and photography specifically. I was also becoming politicized and starting to have a much clearer and more sober understanding of America’s complex and often destructive role in the world. And then 9/11 happened, followed by the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. Wars fought by my country, by my generation, and sometimes by my friends in the military. So between these massive events, my interest in war, photography, and a growing political identity, I began to form a clear idea of what to do with my life. Or at least the basic framework of an idea, which has steadily expanded outwards in the past few decades.

Tell me about the book, or about the photography that led to the book.

One of the earliest images in the book is the picture that became the title — “Sorry for the War.” In 2013, I passed a storefront art gallery in Manhattan that had a pop-up show called Balloons for Kabul. Inside, there were all these pink balloons floating around, a pingpong table, and pink Post-it notes where people were invited to write to the citizens of Afghanistan. The notes would be handed out to people in Kabul on their morning commute as a show of solidarity from the people of New York. It struck me as sweet, but hopelessly disconnected from reality — both tender and absurd at the same time.

At that point, I had been covering these conflicts for almost 10 years and feeling frustrated at how small and meaningless my own contribution was, despite the enormous risks I was taking. The starkness of the note reading “Sorry for the War,” in all its sincerity and helplessness, struck the right tone for a work I intended as my apology for these intergenerational wars.

Every book I’ve done starts with a loose idea. Photography is a mystical and magical thing, and you don’t really know where it’s going to go and what it’s going to give you — it has a lot to do with the places where you find yourself, the people you meet there, the unexpected instances that resonate. In those early months of working on the book, I found a few things that stayed with me and helped guide this work.

One was a trip to the 9/11 museum. I took a picture of a mother and a daughter in front of a lightbox of the towers exploding. It’s a surreal museum, dedicated to just that one tragic day, but it misses the point that 9/11 was not just about that day, it was about the history that led to that event and all that has followed. To focus on the day and not the continuum seemed like a missed opportunity. I understand how difficult it is to do justice to that history in a museum — our narrative of this era is disjointed, still in motion, and above all deeply politicized, but it became an important thread I wanted to follow.

The work was also deeply shaped by ongoing conversations with friends of mine from the Middle East and the countries we are at war with. They encouraged me to focus more on documenting the often invisible and anonymous people from their homelands. In the United States, we obsess almost exclusively over the experience of American servicemen, while the Iraqis and Afghans — amongst others — caught in the middle of the United States’ often incoherent and contradictory foreign policy are the true victims of these conflicts.

One of the interesting things about the book is that it shows examples of the horrific effects of war, interspersed with people who are tangentially inflicting that hurt and pain but doing something very mundane, like standing next to a package.

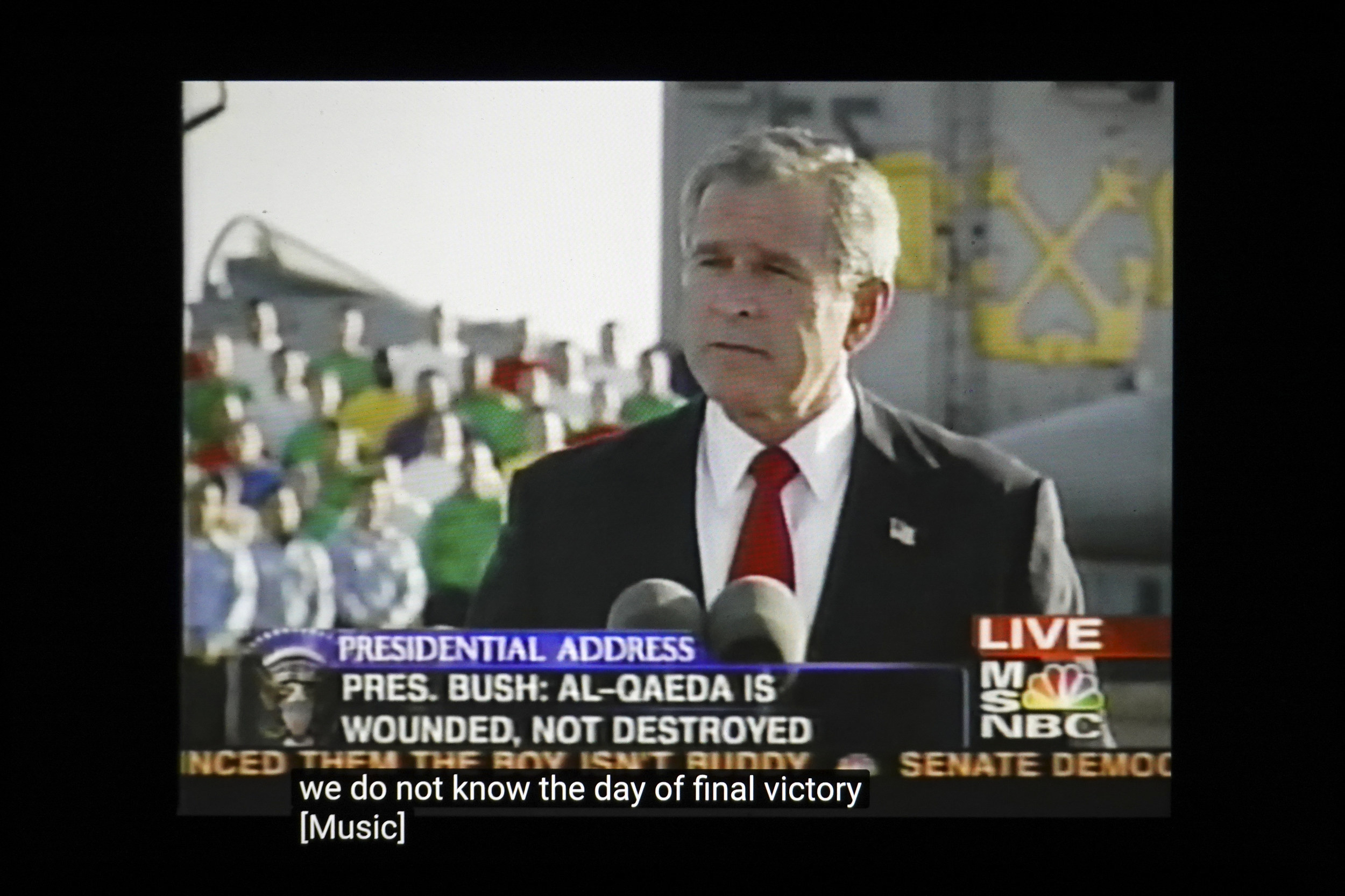

So much of this work is about the forms of subtle violence that create and sustain conflict. Unlike my prior book Disco Night Sept 11, much of the violence in this book is disconnected from danger. Artillerymen in a base in Mosul firing rounds into the old city from miles away. Weaponized drones, a critical part of modern conflict, being flown from another continent. Photographs of politicians who are enabling these endless wars through the decisions they make and the interests they are beholden towards. And then there are images of American society: what we believe, how we are influenced, and how we give politicians the license to both sanctify and commit to war in our name. In some way, everyone in this country is incriminated by the violence contained in the photographs in this book. We are a democracy. We can resist. I believe that still means something.

What do you want people to take away from this work?

I want people to reassess what they think they understand about this era of history. I think our collective understanding is generally very superficial. I get that. Not everyone is going to take a deep interest in the subject matter. But though most of us haven’t been personally exposed to these conflicts, they still nonetheless rage on, and their consequences reverberate everywhere in our lives. Nationalism, the ever-widening partisan schism, Islamophobia and racism, isolationism, economic costs — 5.9 trillion and counting... all have been exacerbated by the long tail of these wars, and that has enormous impact on our lives and our choice of the politicians we elect to lead us. And this is only to speak of the United States. After 20 years, we hardly know a name or a face of an Iraqi or an Afghan, while recent estimates claim up to 480,000 dead and 10 million refugees. These are unfathomable numbers. I’ve covered these conflicts for 15 years, yet I’ve seen only the tiniest pinprick of the total suffering. Yet that’s still been an utterly devastating experience. So I hope that when you see these simultaneous realities laid out before you, the familiar and the unfamiliar, you ask important questions of yourself, and perhaps find a way to act. These horrors are ultimately sustained by indifference more than any evil.