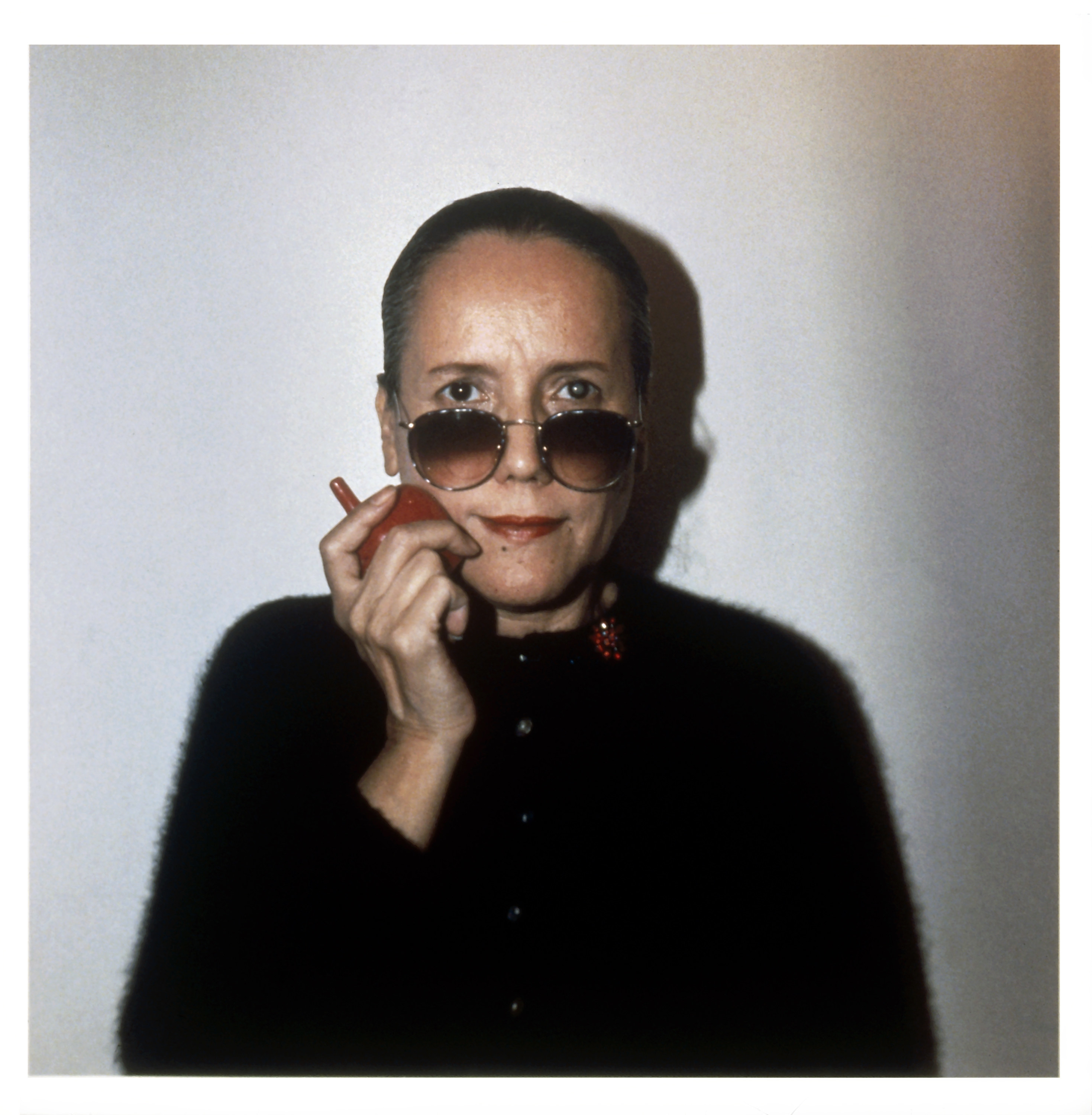

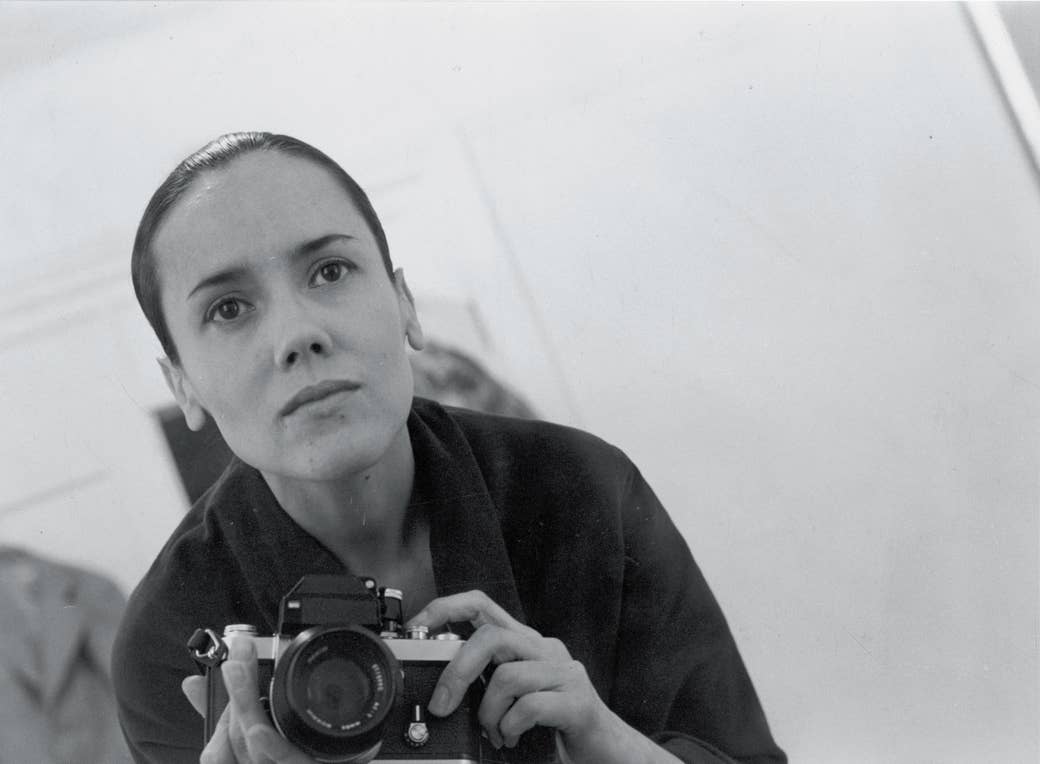

When Sophie Rivera died earlier this year, we lost a fearless and pioneering photographer whose passion for self-discovery was unparalleled. As a freelancer in the 1970s, and as a woman of Puerto Rican descent, Rivera really had to “hustle” for assignments, said Dr. Martin Hurwitz, her husband of 60 years. She was an early founding member of En Foco, a photography workshop turned nonprofit arts organization founded by a group of photographers who were also Nuyorican, or Puerto Ricans living in New York. She is best known for her Nuyorican portrait series and her radical self-portraiture.

Hurwitz met Rivera at Orchard Beach in the Bronx in 1961. “She had a camera when we met; she took some pictures, but she worked as a belly dancer at the time,” he said. When she realized that belly dancing wasn’t going to be her full-time career, she segued into photography.

“Photography gripped her,” Hurwitz said. “She started taking pictures of everything, the neighborhood. She was my wife, but she was incredibly talented also. She worked really hard at it. She was a good citizen, great artist, and we loved each other.”

Today, Rivera’s work is in museums including the Smithsonian and the Brooklyn Museum, galleries, and private collections all over the world. Rivera also practiced street photography, taking pictures of Latino residents and neighbors in her Morningside Heights neighborhood. As a street photographer, she was eclectic and independent. She could also be critical of her peers in the photography world, many of them white men.

“One of the things that she’s important for, she was a true feminist,” said Cecilia Fajardo-Hill, an art historian and independent curator of over 30 years and a champion of Rivera’s work.

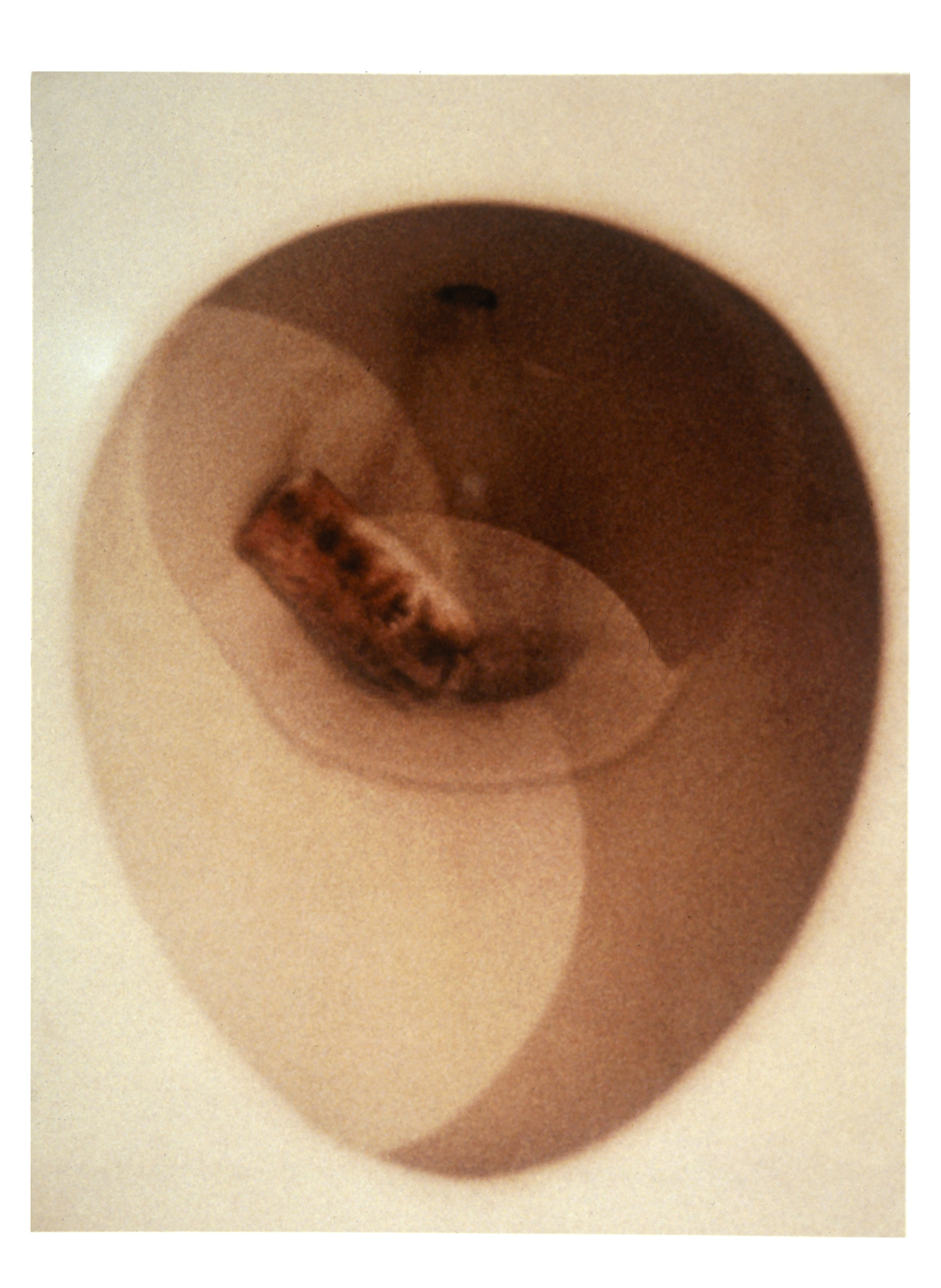

“I don’t really know as much work as powerful as hers,” said Fajardo-Hill. “Her most important work is extremely intimate, about herself and about Martin and about the body. In her Rouge et Noir series, she celebrates women's bodies through these still lifes, even when they’re a still life of a toilet bowl. I think that the way she beautified this is important.”

Of the Rouge et Noir series, Marcela Guerrero, an assistant curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, said that Rivera “granted viewers a new vocabulary of abstract photography that is at once feminist, conceptual, and revolutionary.” Her self-portraiture “is literally her body: She is the possessor, agent, and object of her own photographs.”

“We can’t just think of the images; we have to think of the artists behind the images. And she was a master of photographic art,” said Fajardo-Hill. “She’s left us with this iconography that has left us with the beauty of Nuyorican people [and] the beauty of the body.”