Cinthya Santos-Briones is a multi-hyphenate like no other: She’s an artist, anthropologist, professor, ethnohistorian, and community organizer based in Brooklyn. Her photography and collaborative projects all stem from the social problems that affect her community. Her pictures of Indigenous Mexicans in the United States are regal and tender, informing our understanding of how diverse Mexican culture can be in a single city. By allowing her viewers to hear directly from the participants involved, Santos-Briones is looking to broaden their understanding of the nuances of Mesoamerican cultures, which have often been silenced under traditional colonial narratives.

Informed by her previous work as an anthropologist in Mexico as well as her time as a community organizer, Santos-Briones rejects the traditional role of a photojournalist, saying that the people that she photographs are co-collaborators and she plays the role of producer or just one of the authors of the project. “It’s the idea that the system tells you that you are the artist, you are the author — you know, individualism,” she said. “Photographers don’t discover stories. We need to be more collective than individual.”

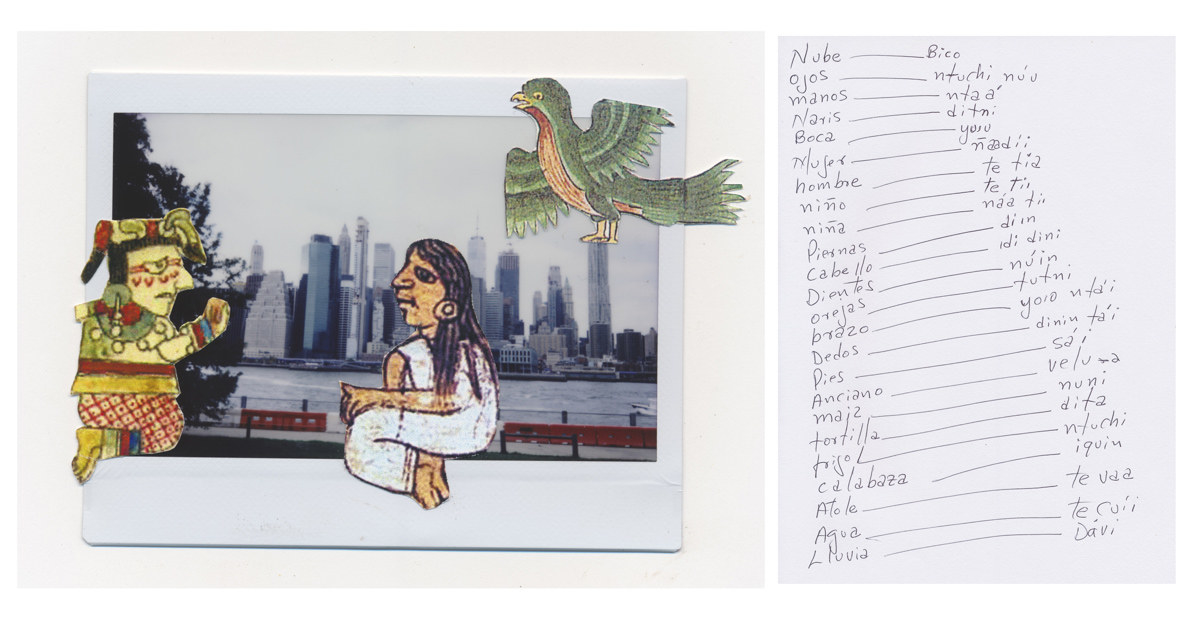

As a Mexican woman living in New York City with Indigenous roots herself, Santos-Briones is interested in highlighting the diverse cultures of Mexican Americans in the United States, and the diverse experiences of the individuals who work with her on her pieces, through drawings or what they choose to wear in the photos.

We spoke with her about the importance of challenging the colonial narrative, the role that dance plays in her photography, and how she makes the grandmothers in her work happy.

Tell me about yourself.

I’m a Mexican migrant. I have Indigenous roots with the mestizos, and I used to be an anthropologist in Mexico. For around 10 years, I worked as a researcher for the National Institute for Anthropology and History in Mexico. I focused on Indigenous immigration, codex and textiles, and traditional medicine. When I moved to the United States, I was doing my dissertation on cultural anthropology about Indigenous migration, focusing on an Indigenous Otomi community in Flushing.

I mix my backgrounds a lot — my methodologies and ethnohistorian tools. I try to create in my practice not just an aesthetic, but also a political work that serves as a reflection of social empowerment and a community impact.

I worry a lot about how the media has represented not just people of color and not just migrants, but also women and working-class communities. My aunt immigrated in the 1980s to South Carolina, and that had a huge impact on my life. She left home with my cousin, and they couldn’t come back home because of their status.

Since I was a child, I was impacted by these policies and these displacements — my family has been separated by these policies. To put all the migration experiences into one box is a mistake; everyone has experienced it in a different way. My husband came as an unaccompanied child and became a citizen — now he’s a minister. In the end, we all have these experiences.

How did your family and people close to you influence your work, from anthropology to your photography?

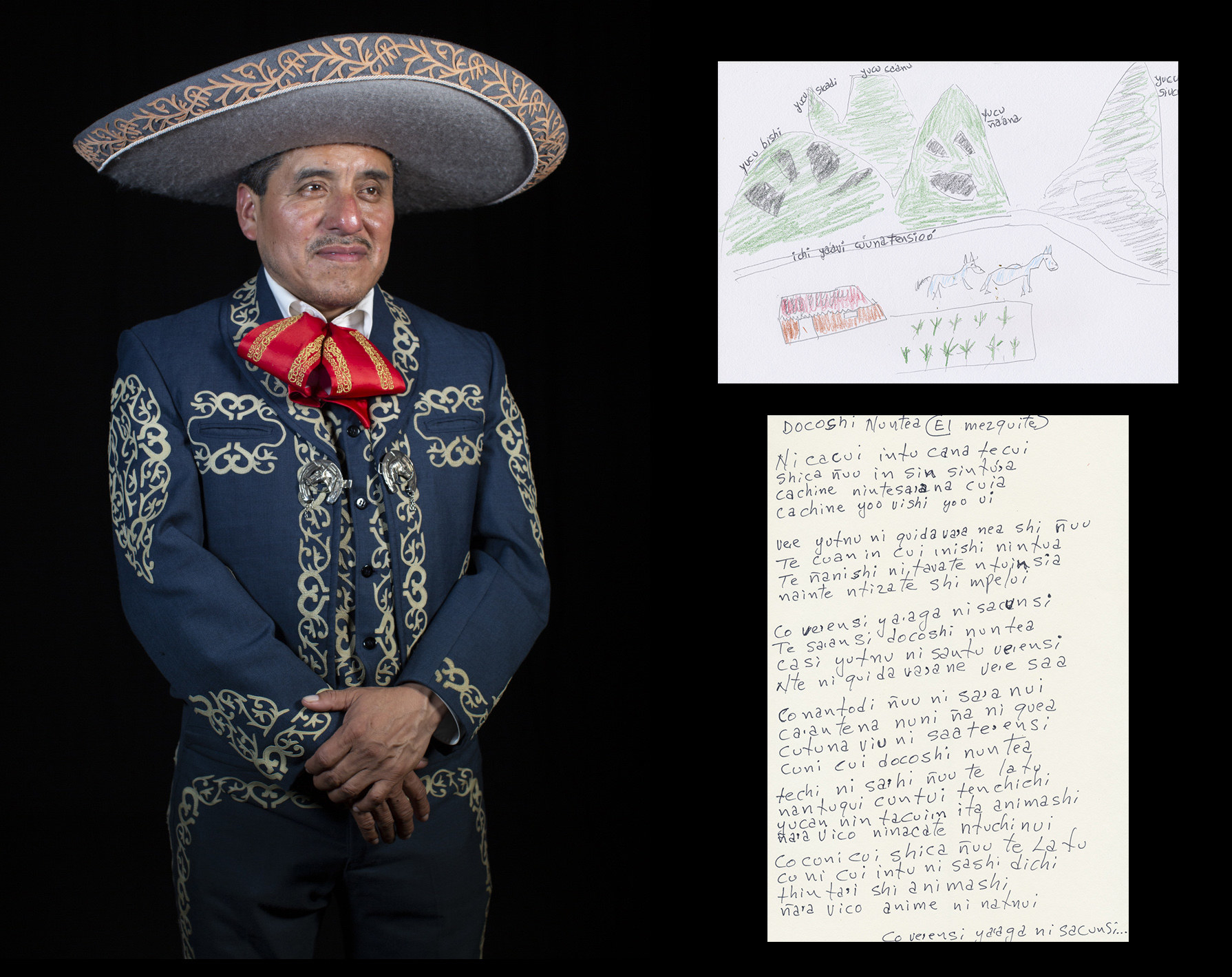

My grandparents inspired me a lot to be what I am. I grew up in a small town, my paternal grandparents were rural teachers of Indigenous origin, [and] on my mother's side, my grandmother was a photographer and my grandfather was a charro [rancher] and was dedicated to the production and sale of pulque, an ancestral alcoholic beverage that dates back to the prehispanic era. Since I was a child, I was brought up to be proud of my Indigenous roots with the Mestizos, and at home I was surrounded by books by my parents. My mother is a teacher and my father a self-taught intellectual.

I was very exposed to my culture since I was a child. I spent time in Indigenous communities in the region where my paternal family is, listening and dancing huapango, which is the traditional music of that region. I think that encouraged me to study anthropology and history.

Through anthropology, I fell in love with photography. I spent 10 years working and living in Indigenous communities in the cultural region of Mexico known as Huasteca, where my family is from. There, each blink is an image, the sunsets are beautiful, everything: the food, the parties, the rituals. At that time, I was not very good at taking photos, but that encouraged me to do what I do today. My grandmother also exerted an influence on me, for the love of photography, since she was a photographer and the family chronicler, she gave me her camera and now I am working on the family archive that she created as a family memory.

There’s a lot of history in your work — how did you decide to develop this?

Since 2011, I have been working with Indigenous women, photographing them in costume. I have known many of them for a long time. For me, photographing these women is like coming back to the past. A lot of the portraits are with the Maya and the Ki'che community, trying to understand the Mayan feminism, if that concept exists in these communities. Women are so proud of wearing their own clothing, and to show the beauty of these Maya people, I want people to understand who are the descendants of this culture? Of the Otomi, Maya, and Aztec civilizations?

Looking at the migration of these people now and looking into the past, it’s fascinating. I know that the people I work with now are super hard workers, they are domestic workers or nannies, but who they are in terms of their identity and language is something else. Some of them don’t even know how to write in their own language, so for me, it’s super important to highlight how language is a way to see the world and to think, to be in your own language. Especially in New York, where there are over 600 languages spoken or more, language is a part of our environment.

How do you talk about this with students, and encourage them to find something that makes them so impassioned in their own work?

I teach in the photojournalism school in CUNY, it’s what I studied myself at ICP. I try all the time to bring into my classes the idea of how can we be ethical, how can we question ourselves when we’re going to start a project, why am I the right person to tell this story, how am I going to approach the people in this community, what is going to be the exchange. I try to tell them to reflect on these questions in their practices, and to be careful about different kinds of social problems — if you are going to photograph people who have been in detention or are in the deportation process, how is this story going to affect the people involved? Reflect about the economy of the image, and how the media can earn a lot of money selling this image. Being conscious of the narrative, and thinking about how we are going to not only contribute to photojournalism as a discipline, but how the students can transform the lives of the people they’re photographing.

Are you making work more for the people in the community, and the preservation of their culture, or for people outside the community, and sharing it broadly?

Culture is not aesthetic. It changes through others. I want people to see how the culture is changing, their point of view and how they carry on their own identity. When I was working in anthropology, people would point out the fact that an Indigenous community was using cell phones as if that made them less authentic. It’s going to change, you know? That’s how it is.

For example, there is a hip-hop style that these Indigenous people are creating, but at the end, they are dancing a traditional dance in their videos. It’s a new generation, and people get to decide how to define themselves. You identify yourself with your community first, and with so many immigrant communities in the US — the Arab community, the African community, the Asian community — it changes. These beautiful civilizations do have a past. These women are wearing history and they are dancing history.

What do you want to see change in the photo industry?

Perhaps it is somewhat utopian, but I would like to see a less capitalist and more communal photography industry, more diverse in terms of class, gender, and race.

A lot of the time, we hear about the race, but it’s interwoven with other things. I want to see not just women, and not just women from the barrios, and not just people taking photographs in their own communities. We need to give all people access to participate as photographers.

I always wonder if we need more egregious images of migrants at the border in the “photography industry.” For what? To know that human rights continue to be violated? To change laws? To sell and become famous? A crucial [change] for me would be for the industry to function more as a space for reflection, taking up concepts and ideas from political philosophy, to question the historical link between colonialism and photography and how we continue to reproduce colonialist practices in the photographic act. Is it important that as photographers, we challenge industrial logic, that we reflect on the challenges that photography faces in this context of history.

I want to see more inclusivity in race and social class. A lot of the time, we hear about the race, but it’s interwoven with other things. I want to see not just women, and not just women from the barrios, and not just people taking photographs in their own communities. We need to give all people access to participate as photographers.