Three men were killed and dozens wounded when police opened fire on a group of college students in Orangeburg, South Carolina, on Feb. 8, 1968. The event, which became known as the Orangeburg Massacre, happened four years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act supposedly abolished Jim Crow laws and ended discrimination by race in public places. The students had been holding peaceful protests for a few days and staging walk-ins at the All Star Bowling Lane, a bowling alley that remained segregated. Protests against the shooting ensued, although no one was ultimately charged for the deaths. It remains well known in Orangeburg, where it’s commemorated yearly, but is lesser known than other acts of violence during the civil rights movement in the South.

Cecil Williams grew up in Orangeburg in the shadow of two Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs): Claflin and South Carolina State University. He graduated from Claflin University in 1960 with a degree in art and stayed on at the campus as the official photographer. He photographed the day of the shooting as a part of his job.

Williams remains at Claflin today as the official photographer and maintains their large archive, which includes the Cecil Williams South Carolina Civil Rights Museum. We had the honor of speaking with him about that day and its legacy in a time when we’re thinking more critically about police violence.

What happened leading up to the massacre?

The Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964, and the Voting Rights Act passed in 1965. Most Americans had procured freedom from the Jim Crow laws — they could eat in restaurants and go to schools that were properly equipped. But there were still some pockets of resistance in 1968. Orangeburg All Star Bowling Lanes was midway between the college campuses and downtown Orangeburg. Any person walking from the northern to the southern part of town would encounter these signs on the bowling alley that said “Whites Only.”

Students started going to the bowling alley to try to integrate it. On Feb. 6, 1968, the activity geared up. I was called in to photograph it. As the photographer of SCSU and Claflin, I took images of all of the student activities, sports and dances, and anything from the civil rights movement that preceded that time. When I heard that the students were at the bowling alley, I drove down there. My camera didn’t have any film in it, and I was fumbling around in my car trying to fill it before I went to the bowling alley. The students were almost surrounded by state police, city police, and a South Carlina law enforcement division. The students were asking to go in, but the owner said that his place wasn’t under the jurisdiction of the Civil Rights Act; he has plenty of customers all year long and he didn’t need any more customers. It was a membership organization, is what he said. Some white students had tested that, and tried to enter as nonmembers and had been allowed in.

One of the students pushed against a glass pane in an adjacent building and broke it, and everyone started running, including me. I turned my head around and saw a young lady fall to the street, and saw two Orangeburg police officers beat her with their clubs as she was on the ground. The violence started then, on Feb. 6.

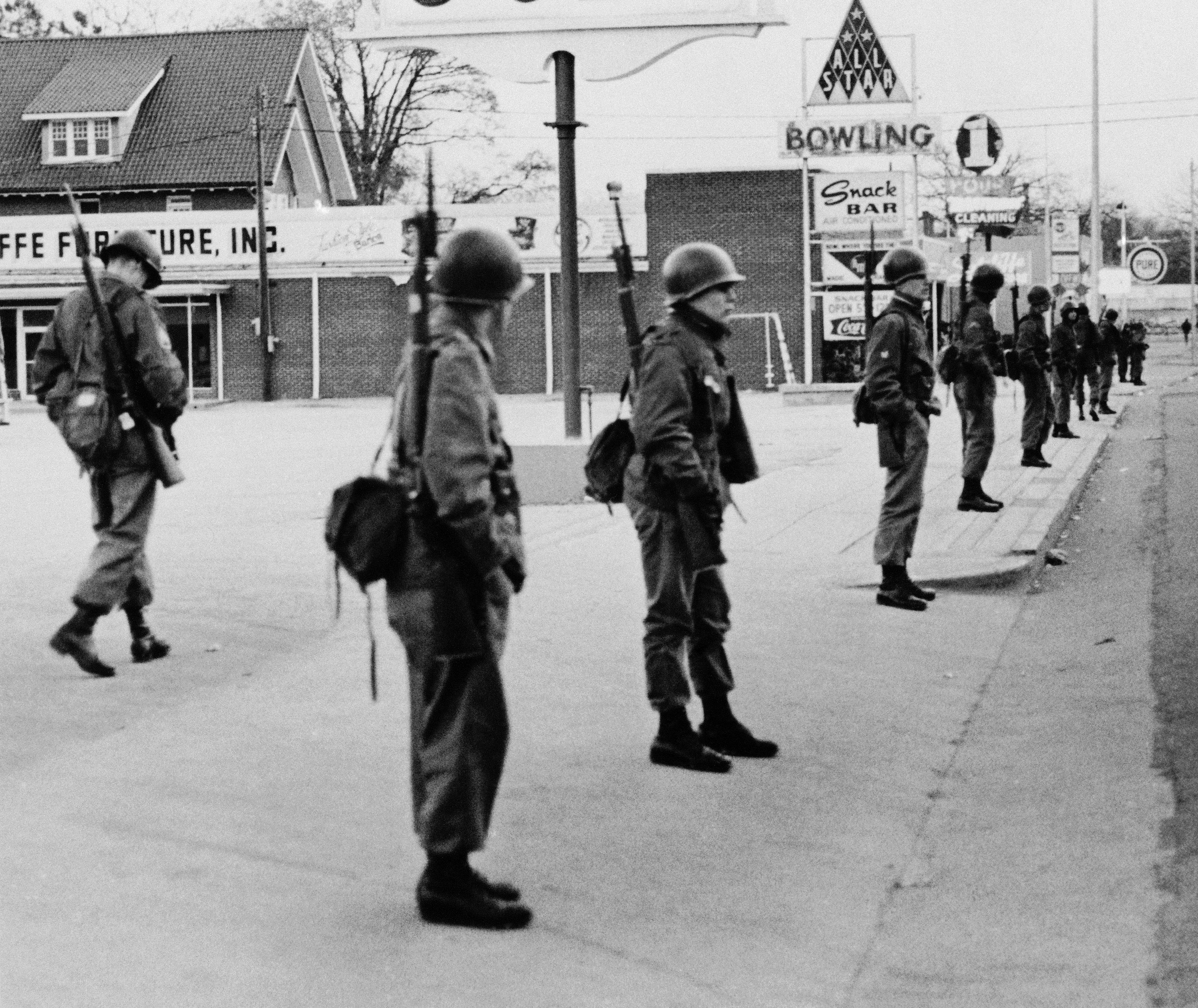

Two days later, on the eighth, the students were prevented from leaving their campuses. On the street in front, the state had called in the state police, the National Guard, everything. I got to the campus at dark and I left about 9 p.m. to get something to eat. When I finished eating, I understood that there was a confrontation on the campus and I couldn't get back on. At 9:30, there were 21 highway patrolmen at the scene. A highway patrol officer ordered his officers to load their weapons, and nine highwaymen obeyed him. Those people fired on the students from behind a hill on the campus green, and it became known as the Orangeburg Massacre. A lot of people think it occurred at the bowling alley, but they were on campus.

What was the fallout immediately after?

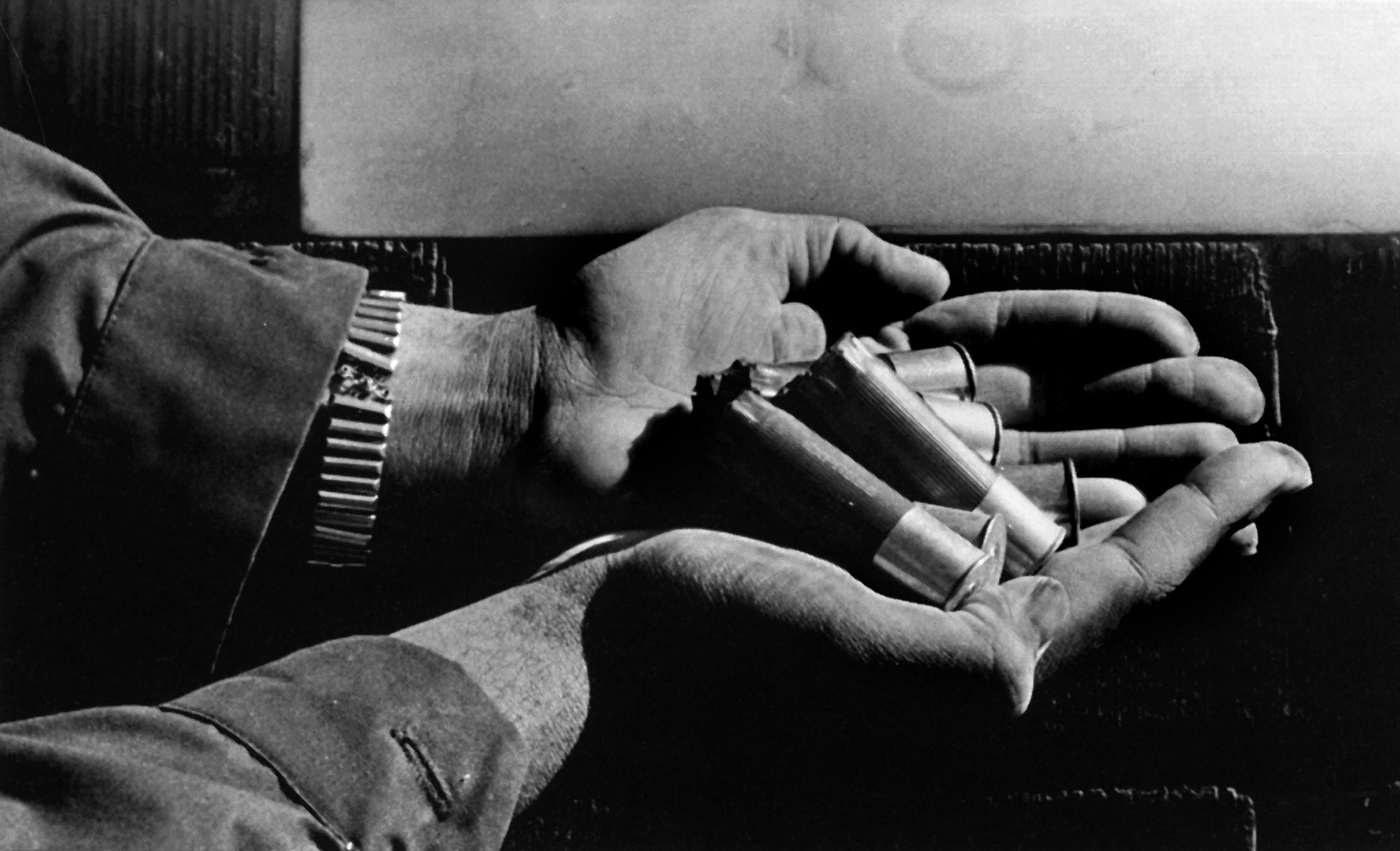

Phones in Orangeburg stopped working on the night of the eighth, and the newspaper tried to paint the picture as being an exchange of gunfire. The students had no weapons. When the law enforcement officers left the scene that night, they didn’t even have the respect to put a crime scene incident tape around the scene [with the bodies]. The next morning, Feb. 9, I went to the area and picked up shotgun shells. Later, these shells were used to testify which guns the officers had used in the trial, and I stood to testify at the trial myself in the federal trial in district court in Florence, South Carolina. After a deliberation of about 30 minutes, the highway patrolmen were found to be innocent. They weren’t charged with anything.

What was the aftermath?

This was the most violent act that had ever happened [in Orangeburg] from the 1950s through the civil rights movement. The [Civil Rights Act] laws had erased the outward racism, but Orangeburg was still a very divided community. There were some token things done to reach out to the African American community, such as some people finding jobs. It would be in the paper, someone was the first Black person to do this or the first Black person to do that. There was advancement, Black police officers hired, Black sheriffs officers hired, and Black people taking positions in the country, state, and district government jobs that had been held by white people my entire life.

What does it feel like now to share this history with students at the university?

Before COVID, there were annual programs in Orangeburg talking about the history and what happened. The most I can offer is the story, the violence of law enforcement, who were the first to start the violence, from the beginning beating a young woman because she was running away. It turns out that law enforcement officers react violently if you don’t obey them. If you aren’t obeying the law, they should try to arrest you, but they shouldn't try to break your body or cause any further harm.

As you have seen, law enforcement officers throughout history have acted with very little tolerance towards Black folks. Even today, law enforcement is still discriminatory against people of color. If they are going to set up a speed trap today in Orangeburg, it’s going to be in a Black community. Even today when there are Black officers serving alongside white officers, there’s a stigma that Black people are the only ones committing any crimes.

South Carolina has become more understanding, [people] act with a greater degree of harmony. There is no argument that change has taken place. Now, our city council is almost all Black, except for one white city councilperson. Not that this was the intent; it’s an elected process and this reflects the population.

How does it feel to know that we’ve come this far, but to see that we're still struggling with many of the same issues?

It’s not surprising. Law enforcement officers have gotten away with it until very recently, when they killed George Floyd, that was a rare [response], but it sent out a signal. But even on the TV tonight, I saw that police officers broke into an apartment and began firing and killed the person who was sleeping in the apartment. Even if he was in the wrong, selling drugs, the most terrible type, he’s dead now and he can’t stand in front of a jury and defend himself, tell us what happened. Law enforcement needs to be more thoughtful and careful; they are breaking the laws even though they're trying to enforce them.

People talk today about the law enforcement and how uneven it is. They seem to forget that this isn’t anything new. It’s been something that has been happening to African Americans historically, it’s always been there. Lynchings, and the uneven, unethical, and unfair way that law enforcement has treated us. It’s no wonder that we have a hard time selling democracy around the world when we ourselves do not often treat people of color, Indigenous people, minorities with the same respect that is extended to white citizens. It’s an ancient thing, and I hope that people are able to realize that it’s systemic. Unless they take some very bold initiatives, it’s not going to go away. It can’t be changed by getting new people in law enforcement, our laws and our training must change. I don't think that defunding the police is the answer. Certainly we would all feel less safe and secure if that happened. But we should certainly retrain [police] to respect all citizens regardless of their race. This country has come a long way to recognize what is fair.

Look at Donald Trump, a white American citizen who grew up in a time when whites were considered superior, and people valued the Caucasian race above any other. The hate and racism in this country has again come to the surface under him, four years of a bad president and a bad administration. We should never let what he stands for and what kind of person [he is] rise to power. We have some serious reckoning and reform to do. Whatever makes democracy work in the United States. We are still probably the best type of democracy, but it still has to be tweaked.