One of the most important Harlem photographers of the early 20th century wasn’t planning on being a photographer at all. James Van Der Zee moved to Harlem, New York, in 1908 as a young man because he wanted to make a living as a musician there. Van Der Zee was an accomplished pianist and violin player, but he followed his interest in photography to try to pay the bills. He and his second wife, Gaynella, opened a photo studio first called the Guarantee Photo Studio and later the G.G.G. Photo Studio. “For almost five decades, he was the photographer of Harlem,” said Diane Waggoner, a curator of photographs at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, since 2004.

Waggoner has organized a current exhibition of Van Der Zee’s photographs that will run through May 30, 2022. It was recently announced that his entire archive of some 20,000 prints, 30,000 negatives, and other archival material was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in partnership with the Studio Museum of Harlem from Donna Mussenden Van Der Zee, who Van Der Zee married late in life after Gaynella’s death.

Van Der Zee’s portraits remain a vital link to the Harlem Renaissance as well as to Black life in general in the early 20th century. He was incredibly influential to the next generation of photographers, especially Black photographers. Dawoud Bey has spoken about looking to him for inspiration for the High Museum of Art, and members of the Kamoinge Workshop saw him as a predecessor.

We spoke with Waggoner about Van Der Zee's career and why his archive is still important.

Tell me about Van Der Zee, the photographer.

Van Der Zee had an extraordinary career. He developed a traditional yet distinctive style and took great care to present his sitters in their best light. He not only executed standard retouching on negatives and prints to improve appearances, but he created his own innovative techniques. He often drew on his negatives to add jewelry, such as rings or bracelets, to his subject’s outfits. These adjustments not only improved the sitter’s appearance, but they also enhanced the beauty of the photograph itself by adding sparkle that draws your attention. Van Der Zee also sometimes combined negatives to add a special narrative dimension to his photographs. For example, in funeral portraits, he might include a vision of Jesus and angels to give solace to the deceased’s loved ones.

How did he become so beloved in Harlem?

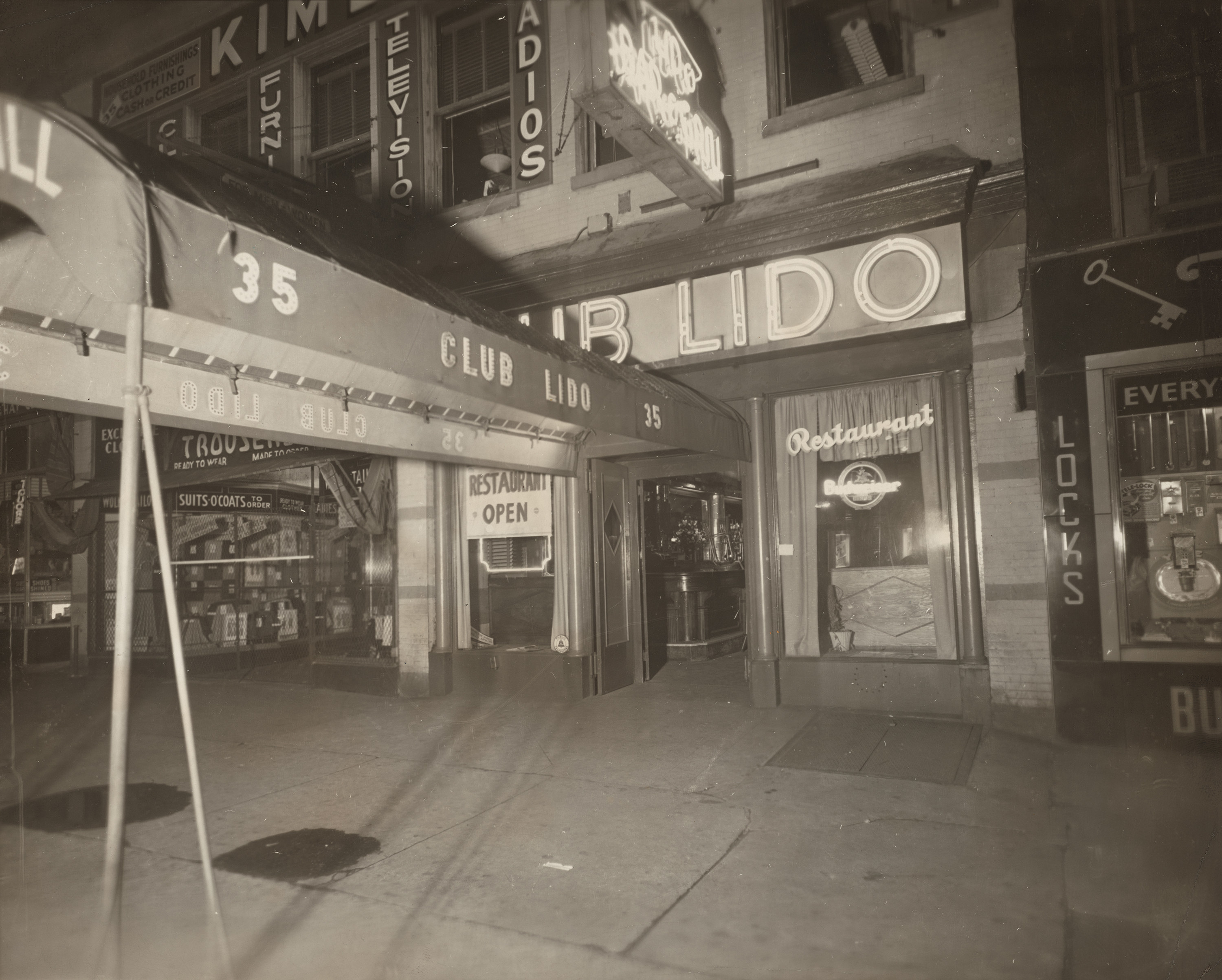

Van Der Zee was a studio portrait photographer, but he was also a vital member of the Harlem community who created pictures that were sources of pride. He was the photographer of choice for religious groups, social clubs, fraternal organizations, sports teams, and others. He photographed many Harlem storefronts, documenting Black-owned businesses. In 1924, he became the official photographer of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, the organization founded by Marcus Garvey, a political activist and leader of a Pan-Africanist movement that advocated for Black self-determination.

Van Der Zee’s skill with the camera was above and beyond most commercial studio photographers. He had an excellent eye for composition. For example, in his photograph of the Alpha Phi Alpha basketball team, he has mirrored the shape of the Greek letters in the formation of the boys posed on the step. In "Couple, Harlem," one of his most famous photos, showing a couple in raccoon coats stepping out of their Cadillac, he so skillfully captures the geometry of the scene and the different textures: You see the matte surface of the brownstone, the shininess of the Cadillac, and the tactility of the fur coats.

Did he achieve this recognition in his lifetime?

In the 1960s, Van Der Zee’s commercial and studio business diminished. As he described it, it was easier for people to buy their own cameras, so there was less desire for people to pose for formal studio portraits. However, he kept his business afloat by offering a mail order retouching business. People would send in their old photos and he would fix them up and send them back.

In 1969, Van Der Zee’s photographs were included in the Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition Harlem on My Mind. Though the exhibition was controversial for its exclusion of African American painters and sculptors in favor of a multimedia display that included blown-up documentary photographs, it led to the rediscovery of Van Der Zee. The story goes that Reginald McGhee, a younger photographer who was looking for material for the exhibition, happened on Van Der Zee’s store. Upon asking if Van Der Zee had any photographs from earlier decades, he was stunned to find that Van Der Zee had kept his stock of negatives and prints covering decades. The Met purchased some of Van Der Zee’s prints and they formed part of the core of Harlem on My Mind, bringing Van Der Zee’s photography to national attention. Eventually it led to several publications on his photography and touring exhibitions. Harlem on My Mind helped Van Der Zee financially, but it didn’t entirely live up to its potential promise: Van Der Zee and his wife were evicted from their home the day after the exhibit closed.

Tell me a bit about when this show started to take shape.

The National Gallery of Art had acquired its first James Van Der Zee photograph in 2000. More recently, in 2019, we were thrilled to acquire an additional group, bringing the total number of Van Der Zee photographs in the collection to over 50. The exhibition showcases almost 40 of those photographs and offers a select overview of his career.

What do you want people to take away from the show?

Van Der Zee’s photographs are compelling and beautiful, capturing an extraordinarily rich period of Black life and culture in the first half of the 20th century. They are a moving testament to life’s milestones, from graduations, engagements, weddings, and funerals, and often joyful, proudly showing communal events such as parades or gatherings of social groups. Significantly, they are pictures made by a valued and trusted member of the Harlem community for that community.