Many of the images of Indigenous peoples that those in the United States are familiar with are far from the young, vibrant, contemporary Indigenous culture that exists today. As Osage photographer Ryan RedCorn put it to BuzzFeed News, “For too long the underlying strategy around the most widely published photos of Native peoples has been one of lamentation, pity, extinction, and death.” When we say that these photographers are among some you should have been following yesterday, we mean it. We spoke with 15 photographers whose work aims to spread joy, truth, and love.

Josué Rivas is Mexica and Otomi and describes himself as an Indigenous futurist. And from Instagram to TikTok, he is committed to bringing balance to the way we tell stories about Indigenous peoples and reimagining the future of visual storytelling and media. Along with photojournalist Daniella Zalcman, Rivas launched a database of Native photographers in 2018 with an eye toward the future.

Zalcman is a documentary photographer and the founder of Women Photograph as well as cofounder of Natives Photograph. “I don't have an obvious community,” said Zalcman. “I joke that my beat is the legacy of Western colonialism, because as a Vietnamese American Jewish woman from DC,that's a defining part of my identity.”

After she worked on several long running projects in Indigenous communities, she said, “People would reach out to me for Indigenous stories and I realized I was not the right person to be considered an authority — that this was a problem.” Zalcman and Rivas met at Standing Rock in 2016 and built out the original list of about 30 photographers based on the Women Photograph model. The list launched in 2018, and they’re expanding it soon to reach across the globe and encompass Indigenous peoples from all communities, not just North America.

“We don’t want to look at the photo industry in ten years, and realize that we didn't plant the seeds,” said Rivas. “The media industry is reactive instead of proactive, we wait until the tragedy happens to be documented instead of using our stories to avoid the tragedy from happening.

“We [collectively] need a reimagining of how we think of ourselves as Americans,” Zalcman said. “Obviously Americanness is a complicated thing right now, because all of a sudden we're having these complicated conversations about what it means to exist in a country built on stolen land with slave labor. People will often say that this kind of criticism is unpatriotic, but I disagree. If we can't have these conversations in 2020, we're not being honest with ourselves about where we come from and who we are — about how as Americans, we occupy stolen land every day.”

These images and notes from photographers are participating in and shaping the conversation about Native America in 2020, beginning in Indigenous communities from Hawai’i to Lakota Territory to New Mexico.

Kalen Goodluck, Albuquerque, New Mexico

"Kalen Goodluck is Diné, Mandan, Hidatsa, and Tsimshian. The Apache Tears Motel was once a historic roadside stop for motorists in Tucson off Benson Highway and featured a kitsch statue of a cross-legged Indian donning a headdress. It sits on a tract of land illegally seized from Western Apache Bands in 1886 and was sold to benefit the University of Arizona’s endowment. This photo and others was a part of High Country News’ ‘Land Grab Universities’ project, an investigation into how expropriated Indigenous lands formed the foundation of today’s public land grant university system."

Ryan RedCorn, Oklahoma

"For too long the underlying strategy around the most widely published photos of Native peoples has been one of lamentation, pity, extinction, and death. I photograph power, humor, and love, and I do this by collaborating with the folks I'm shooting with by allowing them to be authors in the story about themselves. Government policy, crime and poverty stats, justify local/state/national curriculum and narratives that make violence against Indigenous people and Indigenous land possible. My photos are designed to disrupt those narratives. I do this by trying to execute my collaborations at the highest possible craft level. In the Osage language we say ‘washkan.’ It means ‘do your best.’ And that's what I try to do."

“As a child, I knew I was different from the other children at school, but I could not articulate what that difference was. I was troubled when the textbooks we read spoke about Natives in the past tense — always implying that we no longer existed. We are still here. When you see these portraits, you may find we no longer look like you think we ought to. But that doesn’t mean we are not here. It’s time for a new record of Native America."

Tailyr Irvine, Montana

"In a time where we are all forced to be apart, I hope my photography reminds us what and who we are sacrificing for. My work focuses on telling stories of Indigenous communities, some of which are currently being devastated by the coronavirus. My goal with my work has always been to bring adequate representation to Native American communities, and I think that is especially important now. Photography during a time where we can’t leave our homes is incredibly powerful. A lot of images made in this pandemic have connected us in ways I don’t think the world has been connected before. You don’t need to speak a common language to understand photographs because emotions are universal and allows us to connect with strangers around the world. It unites us in our grief, anger, or happiness. If we have any hope of getting out of this pandemic, we have to care about people in places that have nothing to do with us. I think photography is one the best ways to do that, and I hope my work allows people to connect Indigenous communities in ways they haven’t before."

Jaida Grey Eagle, St. Paul, Minnesota

"My life experience as an Oglala Lakota woman has informed my work by approaching photography with a different mindset. I don't want to shoot, take, or capture anyone, I want to create, collaborate, and make images with my community. My ties to my heritage and an inherent want to dismantle white supremacy are all things that drive me towards creating and making space in the photography world for all of us, not just some of us."

“I’m Matika Wilbur from the Swinomish and Tulalip Tribes. I integrate fine art and social justice as a longform photo documentarian, writer, podcaster and public speaker. Seven years ago, I sold everything, packed my bags, and hit the open American road to begin @project_562, a Kickstarter-funded mission to visit, engage, and photograph over 500 Native American Tribal Nations in the United States to eradicate the archaic, insidious, racist invisibility of Native Americans. The project has been in pursuit of one goal, to ‘change the way we see Native America.’ Since 2012, I’ve touched down in 50 states, traveled hundreds of thousands of miles - by horseback through the Grand Canyon, by train, plane, and boat, but mostly in my faithful RV, the Big Girl. I’ve made kin so many tribal nations, from Inupiaqs in Alaska, to O’odham in Arizona, Tongvas in Los Angeles, Osages in Oklahoma, and so on. Dismantling white supremacy is the work of many, and Indigenous communities have been in this battle since European contact, including with the most genocidal racism and pandemic ever. I believe that Project 562 holds the powerful stories that can inspire our collective consciousness to reconcile its relationship with Native America. It is through the sharing of each other’s stories that we connect and change; it is what gives us hope and inspires us. While Project 562 is part of the great compendium of Indigenous-led work moving towards reconciliation, it is going to take many discussions among us right now and beyond, to get at the source of that work and make sure it is carried through the next generation.”

Tyana Arviso, Southwest Colorado

"The work I create is an extension of myself. It is my teacher and my voice. It has helped me dive into the depths of self-discovery. Photography continues to bring light into my life. The creative journey I hold will continue to expand for as long as I dance with creativity."

Dawnee Lebeau, Waŋblí Pahá, Očéti Šakówin Makóče

“Dawnee LeBeau is an independent photographer from Wakpá Wašté Lakota Nation. She documents the kinship of relatives, land relatives and indigenous food sovereignty across Očeti Šakówin. Dawnee is Itázipčo Oóhenunpa of the Tetonwan Oyate. I would like for my visual storytelling to show emotions of empathy and care. This is a photograph of my dear matriarchs during our tinpsila harvest with our ozu' relatives."

Tomás Karmelo Amaya, Phoenix, AZ | O'odham Territory

"My body of work is centered on healing and more specifically on creating visual medicine through Indigenous teachings. I bring those wisdoms into my practice as an artist to celebrate resilience and to offer more complete narratives and representation for Native peoples. Deficit-based approaches to documenting our communities by non-Natives has done a lot of harm. Countering problematic narratives with ones that are abundance-based is another form of me expressing and defending Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination. We might not all be able to relate through lived experience of Indigenous life ways, but we are all in a constant journey of healing. If my photos help others heal, then I’m fulfilling a spiritual commitment and helping restore balance in the universe."

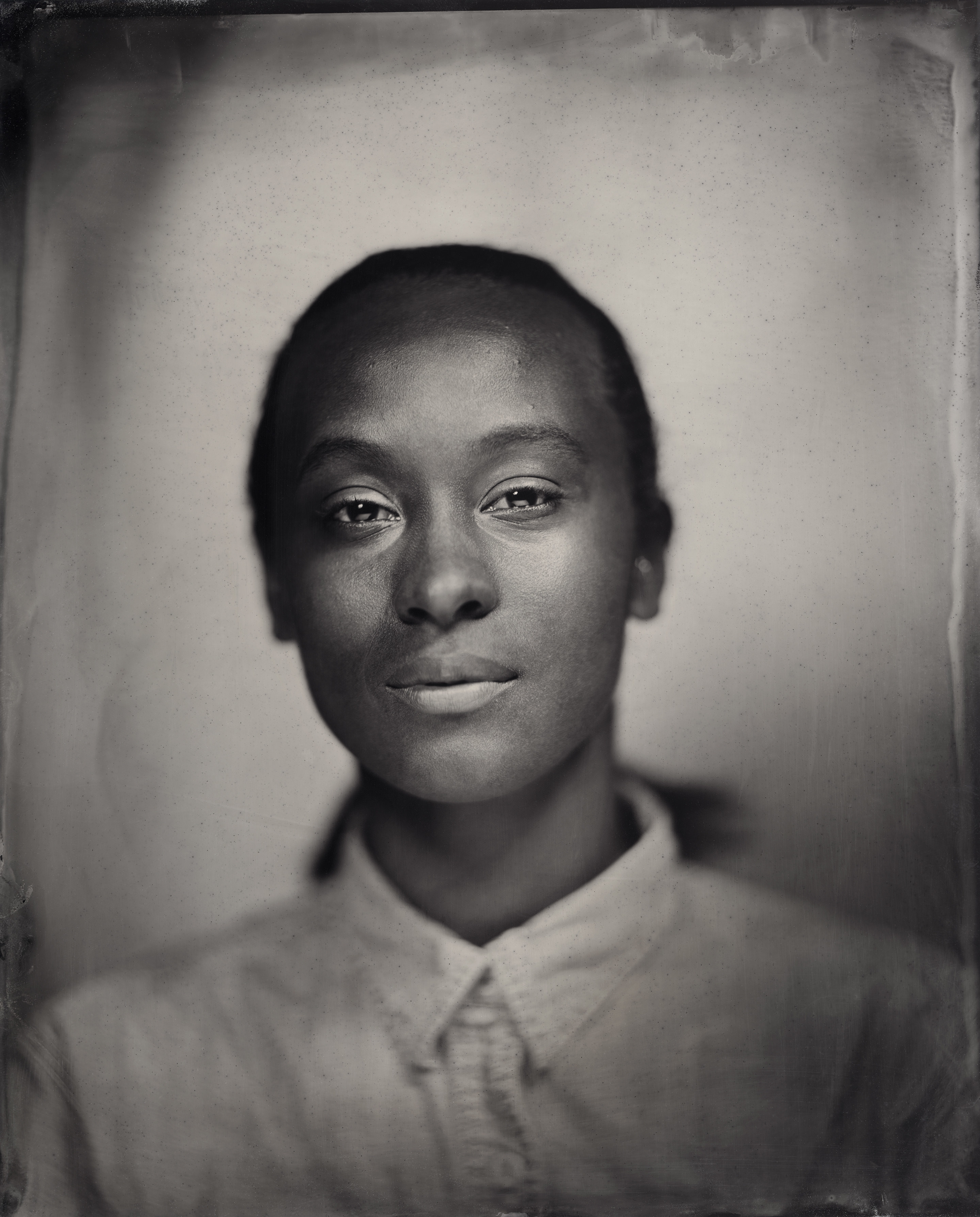

Kali Spitzer, Traditional Unceded Lands of the Tsleil-Waututh, Skxwú7mesh and Musqueam peoples

"Indigenous Femme Queer Photographer Kali Spitzer ignites the spirit of our current unbound human experience with all the complex histories we exist in, passed down through the trauma inflicted/received by our ancestors. Kali's photographs are intimate and unapologetic and make room for growth and forgiveness while creating a space where we may share the vulnerable and broken parts of our stories which are often overlooked, or not easy to digest for ourselves or society. This statement was contributed by Ginger Dunnill, creator and producer of Broken Boxes Podcast, (which features interviews with indigenous and other engaged artists)."

Evan James Benally Atwood, Portland, OR | Ancestral Lands of the Chinook Tribe

"I identify with being a creative, which is malleable in form, so sometimes photographs, sometimes direction, sometimes filmmaking, sometimes words. I enjoy the act of creating joy, documenting joy, especially with Black, Indigenous, POC creatives.

“Every year this ugly tradition happens where settlers boast over roasts about a false history and gather to eat traditional Indigenous plants, erasing so much Indigenous and Black history, watered down every new year. Let this year spark our awareness of our participation, however adjacently to the original only settler families, as harmful acts. This year with the pandemic is the perfect year to cancel your plan to spread a virus (collectively) and stay at home with some pie.

“Identity plays a role in my work simply for existing as a queer brown body, documenting forms, documenting my love for the community around me. When I document my community, it's from my heart and openness to the experiences of everyone around gender. In an Indigenous way, gender is thought of psychospiritually, where Western society only thinks of gender physiologically. The ideas around the latter halts the beautiful balance of femininity and masculinity in ourselves. These days, we must accept change is inevitable, human life isn't meant to be static. Transgender humans are the bravest, kindest, wholeheartedly beautiful I know, and I'll do my best in my work to honor that."

Kapulei Flores, Moku o Keawe | Hawai'i

"Aloha, my name is Kapulei Flores, I am 20 years old, and I am from the Moku o Keawe (Hawai’i Island). As a Native Hawaiian, Kanaka Maoli photographer, being able to capture the culture and spirit of my people is an honor for me. Throughout the years, highlighting the perpetuation of the Hawaiian culture and people has become one of my main focuses in photography. Not only do I strive to capture the culture of my people, but the essence and spirit of them as well. I want to share photos that capture the perspective of Hawai’i through the eyes of someone who is connected to the land and culture of their people. Being able to share with the world that our culture and people are still here and growing stronger everyday, is a way for me to help educate others about the true Hawai’i I know and love."

Nate Lemuel, Dinè Shiprock, New Mexico Navajo Nation

“I had these experiences of being on where I grew up on as a place of healing and comfort. From the start of the day to the end of it really sets in the beauty of who my tribe is. Though it is very difficult to come together at such a time right now, I want everyone who looks at my photographs to get inspired and feel hopeful for the future. Stepping into another perspective in life is growth in my mind. Who I am as a an Indigenous, queer artist is what I convey in my photos, Strong, resilient, and ever-changing. I bring portraits to life, I enjoy directing moments, having conversations with people and the land, and making memories for them.”

Josué Rivas, Chinook, Cowlitz, and Clackamas Territory | Portland, OR

“I want my images to be a reminder of our collective power not only as Indigenous peoples but also as human beings. The intention of my work is to be a starting point for a conversation about decolonization, acknowledgment, healing, and reconciliation, not only with each other but also with all our relations.

My identity is the foundation and serves as a guide for my work. Whether I'm documenting Indigenous movements or creating spaces for us to tell our own story, my ancestors stand behind me and my descendants in front of me. My practice is also guided by the understanding that we as Indigenous peoples will exist in the future; I believe we are in a moment where telling our own stories and reclaiming our narrative is a first step towards reimagining what that future looks like. Technology will shape visual storytelling, and I think Indigenous peoples will be at the forefront of that transition. My hope is that our identity will continue to serve as a reference point for the stories we tell now — we are future ancestors.”

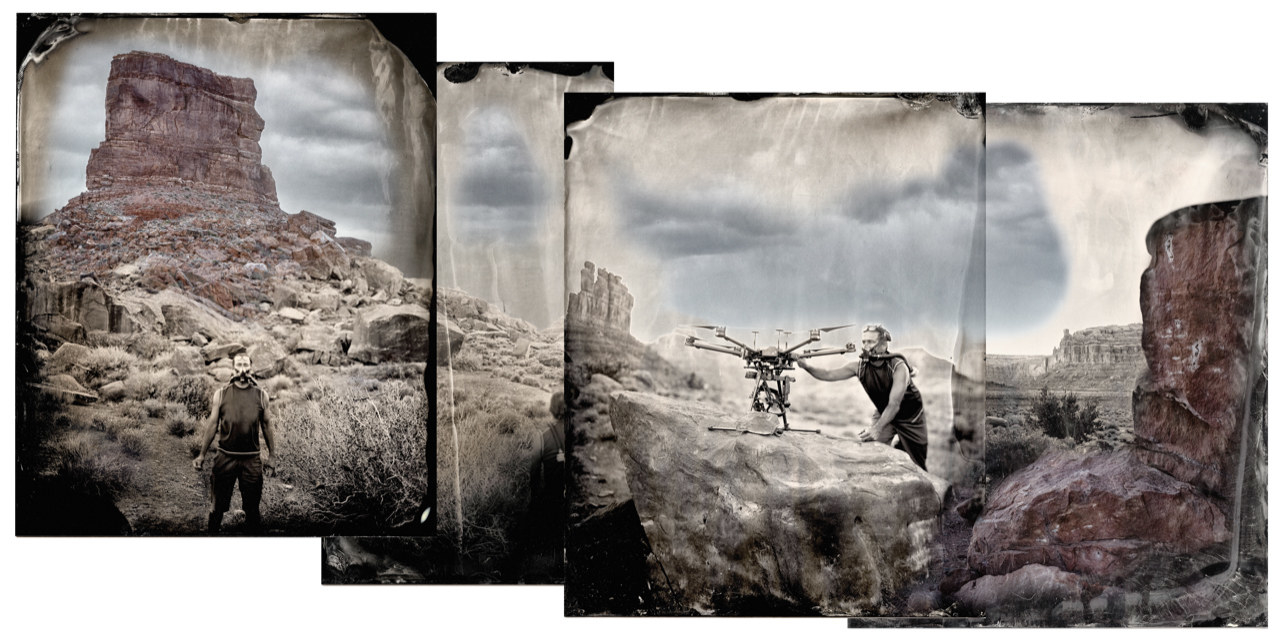

Will Wilson, Santa Fe, New Mexico

"When it comes down to it, I really love sharing the craft. The wet plate process really enables a slower more personal and direct experience of photography, and then there is the gifting of the photographic object to the sitter in exchange for a digital facsimile. I made this recently. It's the AIR protagonist figuring out the drone he uses to photograph Abandoned Uranium Mines on the Navajo Nation. For many of my tintypes, you can engage with the person and collaborator in the portrait through the Talking Tintype app, it's a free download from the Apple App Store. I also run the photography program at The Santa Fe Community College."