Amani Willett has spent years considering the promise of the road, a simulacrum of the American dream that isn’t as straightforward as it seems. In his new book, A Parallel Road by Overlapse Books, he looks at the vastly different experiences of Black Americans and white Americans behind the wheel in America over the last century. With help from family members who contributed their experiences and with the intent to educate, to move people, this book serves to help illustrate the psychological weight of the Black experience on the road.

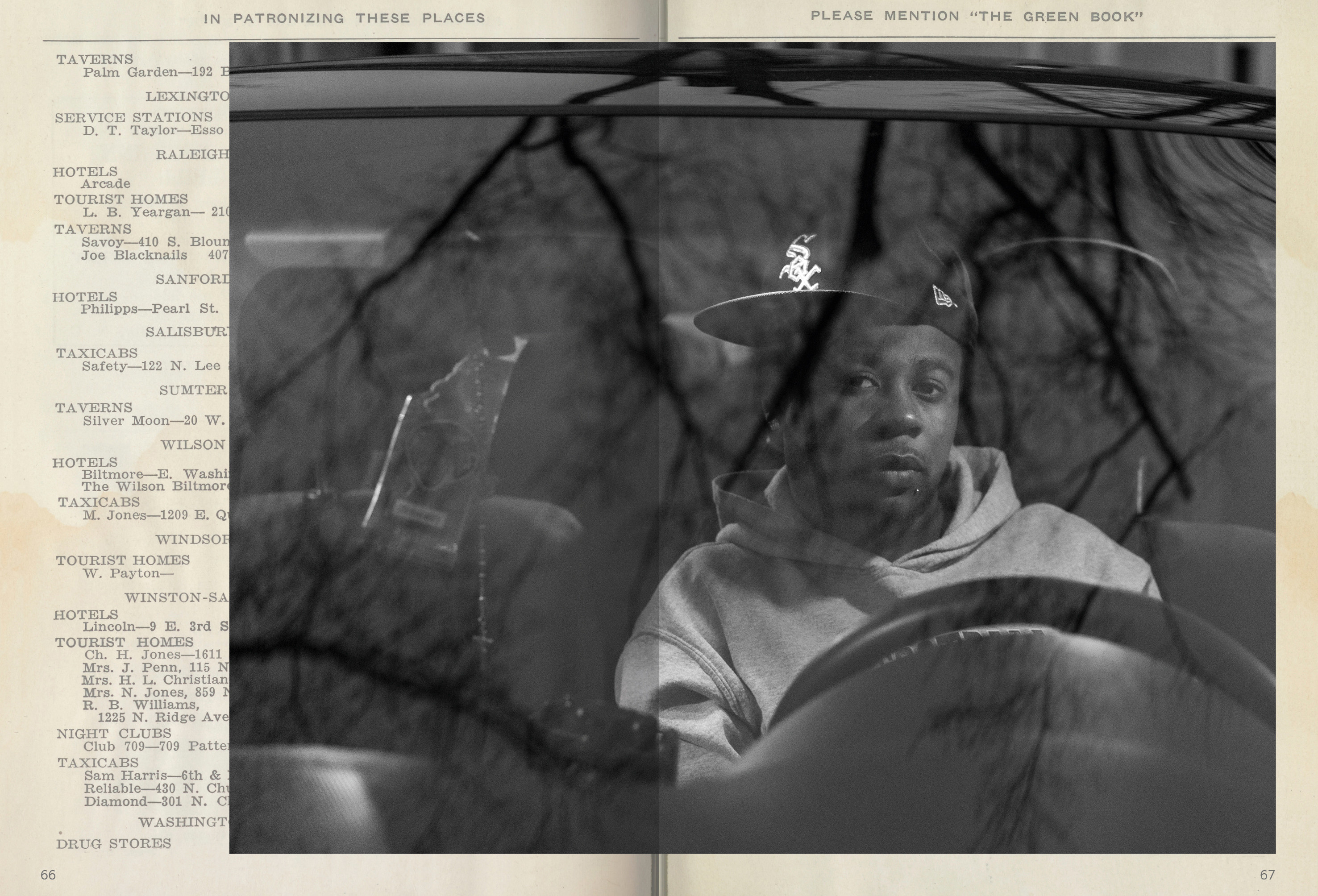

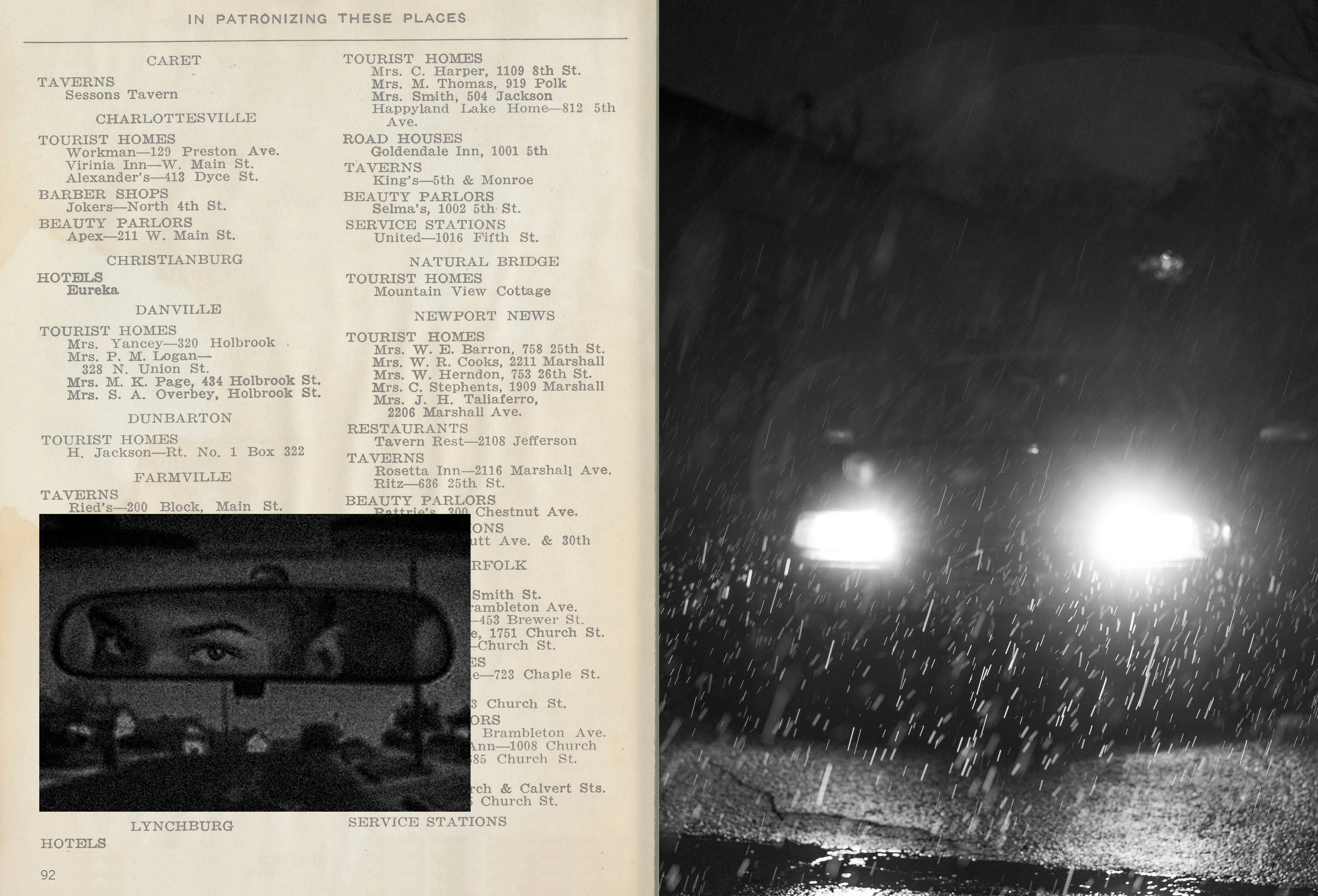

Willett used his knowledge of The Negro Motorist Green Book to shape his own book. The Green Book was a travel guide for and by Black motorists in the United States, first published in 1936 through the 1960s, at the height of the Jim Crow era. It advised Black drivers on where they could safely stop for food, gas, or lodging, as well as dangerous towns to avoid. The photographs in Willett’s book contrast the exuberance of participating in the American road trip, and later, the wary knowledge that for Black people, it can be a dangerous endeavor.

BuzzFeed News spoke with Willett about the project. For more photography news, sign up for our newsletter.

Tell me about A Parallel Road.

My main goal was to create an emotionally resonant, impressionistic experience that shows the trauma that systematic oppression and racism have been inflicting on Black Americans from the beginning of our country’s founding.

A Parallel Road investigates race and the American roads over the past 85 years. In popular culture and literature, the American road has held a mythological position of freedom, exploration, and pursuit of the American dream. In fact, within the history of photography, the road trip itself can be seen as a whole genre of photographic practice. Joining this pursuit has been complicated for Black people and represents just one of the many ways that Black Americans have been denied full participation in the American dream.

What immediately comes to mind is the civil rights movement — and the road as a politically contested space where people have fought for generations for equal rights. It also conjures images of more violent and horrific aspects of the underbelly of American society — as a site of racial violence and fear.

Behind the allure of the road is an unsettling and often ignored history of racial strife that persists to this day. The reality is, for Black Americans, the road has been a site of fear, potential violence, and even death.

A Parallel Road seeks to reinforce the fact that from the beginning of our country’s founding, movement for Black Americans has been systematically controlled and limited.

Was there a moment or a picture you saw that made this click for you as a book?

The idea had been brewing in my mind for some time. Learning about The Negro Motorist Green Book about 10 years ago was one of the events that solidified my interest in pursuing the project more seriously. This was before the Green Book really came into the wider cultural lexicon. The book exemplified the linkage between mobility and freedom; the desire for freedom and to move and experience the American dream in the same way as everybody else.

The other experience that cemented the idea for me was conversations I had with family members and friends. I have a large, close-knit family, and we get together for family reunions every summer. Speaking with them at length about their experiences with racial profiling, harassment, and violence and how scary the road can feel has been both maddening and heartbreaking. Many relatives told me of how they have often thought twice before simply getting in their cars and driving. After hearing more stories from my family and doing more research on the Green Book, I saw a throughline of systemic oppression that was both saddening and horrifying. The mechanisms of how the oppression of Black Americans has been implemented has changed over time, but it’s still the same systemic oppression that has always been there.

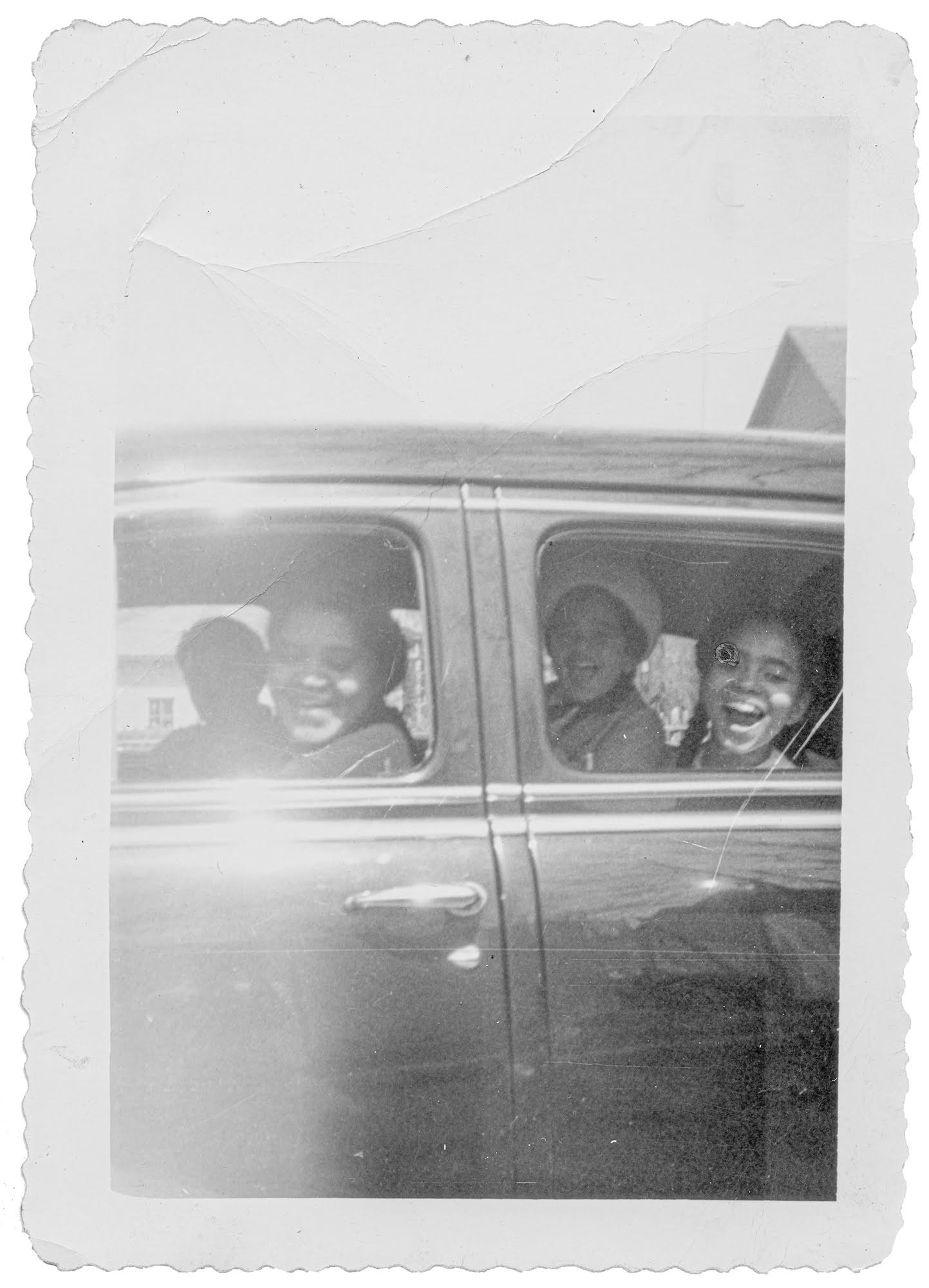

From the outset, I always knew A Parallel Road was going to be a book project. Conceptually, reproducing an original version of the Green Book and then layering an evolving history of race and the American road on top felt like an important gesture. I used advertising images from the 1940s and 1950s to symbolize white Americans' experiences of the American dream. These images at the beginning of the book illustrate the relative freedom, independence, and innocence they experienced while traveling during the Jim Crow era. These images are woven together with archival images of my family members from the 1930s and 1940s that show Black Americans equally excited and proud to be taking part in this new version of the American dream.

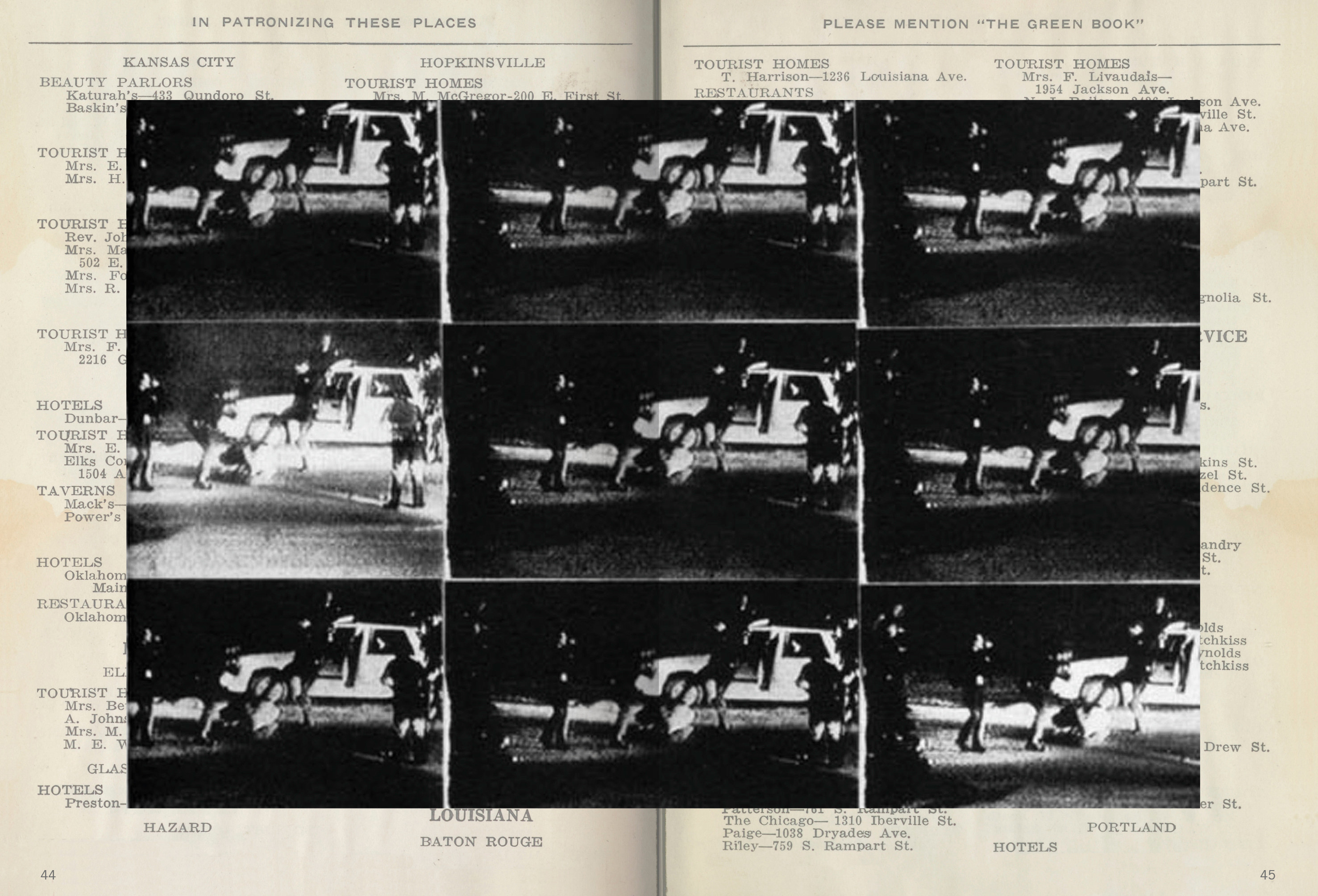

As the book progresses, the narrative begins to become more ominous, with images of car accidents and signs warning Blacks not to be seen in town once the sun goes down. These signs are a reference to Sundown towns — towns all across America where Blacks were forbidden to be at night. If found, they faced intimidation and violence. Deeper into the book, historical images of intimidation and violence against Black bodies are put into conversation with my contemporary images of Black motorists who have been the victims of police violence — emphasizing that the problems of the past are unfortunately still very much alive in the present.

At the book’s end, I attempt to show that despite the history of violence experienced on the roads, Black Americans keep getting in cars and taking trips, refusing to give in to the history of violence and oppression meant to limit their ability to live in the same America that has been attainable for white Americans.

Ultimately, the American road trip is a microcosm for examining race relations in America and symbolizes the larger systemic, structural powers in place that have limited opportunities for Black Americans.

I’m old enough that in high school, I remember the beating of Rodney King clearly. It was an eye-opening moment for me and for many other people. We, as a country, knew there was a double standard, that there were two distinct ways that people were treated. We knew about racial profiling. We knew about police violence. But when you actually saw these inequities being played out on video, it was much more potent. When the videotape footage was released, there were some public outcry and protests. The event caused a slight shift in attitude, but not enough. But it was a precursor to the social media era. At that time, the video footage of the Rodney King beating was a real anomaly. We as a country hadn’t witnessed it before. Now, we see these atrocities in our scrolls almost on a daily basis.

How much driving did you do over the course of those years you were working on the project?

Originally, I planned to drive to many sites listed in the Green Book to see how they had either been preserved or let go to the vestiges of time. But once I set out on these trips, I realized the project was less about the actual places and more about the experience and trauma of driving in this country for Black Americans. The book is a psychological journey. The people and places pictured in the book are not indexically tied to the listings in the Green Book, but they are representative of, and a result of why, the Green Book was, and is still not only relevant, but needed today.

Where did these archival images come from? For many reasons, including racist structures at archives and libraries, so many images of Black Americans aren’t saved for posterity.

I mentioned my large, close-knit family. I sent a call out to them to share any pictures that included them or other family members alongside cars or on the road. Over a few months, I collected hundreds and hundreds of images. The images they so generously shared created a wonderful archive that I was able to use to help construct the book’s narrative. Being able to use the specificity of my family to illustrate larger societal structural issues of racism was really quite profound. It was a sobering and remarkable experience, to say the least. The diversity of images they sent show historical images from the 1930s until the present day of Black Americans standing next to their cars dressed to the nines with a clear pride and excitement about owning a car, images of roadside picnics, camping, pumping gas, racing, sleeping, going to weddings and funerals or on road trips.

Who did you have in mind [as an audience] while you were working on this book?

Of all my work, this has been the project where I’ve thought about that question the most. I hope the book is for everyone, be it people who haven’t experienced this history, people who are younger, people who are white, Black, in the art world or not. There is still so much work to be done around structural racism and everyone has a stake in shaping our future.

I intentionally created a book that has an emotional resonance that I hope people can relate to regardless of their prior exposure to the subject matter — I wanted it to have a psychological weight that people could relate to. Throughout the process of making the book, I was constantly thinking about the challenge of creating something that wasn’t too gratuitously violent or retraumatizing for Black Americans, but that at the same time would also break through the desensitization some people may be experiencing from seeing so many images of violence to Black people on social media. I hope the book serves to move and educate as many people as possible.

So far I’ve been pleased with the responses. Friends and family in the Black community have expressed their gratitude for capturing their experiences and feelings of traveling and exposing it to a wider audience. This week, a family friend wrote to tell me that the power of the book was overwhelming and that it brought back memories of a close friend who was killed on a road trip from Chicago to Hattiesburg, Mississippi, in the 1960s. She said to this day she still has a fear of stopping at a rest stop to go to the bathroom. And I have received many emails from white Americans who have said they will never look at driving the same way again — that because of their white privilege they had never considered the way their mobility and freedom to move about the country was not an experience shared by all.

These responses give me hope that this project can help begin to reconstruct a more complex and inclusive history of this important American experience and symbol. It’s time for this narrative to be reshaped.