In a July 30 note following DreamWorks Animation's second-quarter earnings, where it reported a $15.4 million loss, Cowen and Company analyst Doug Creutz listed as one of just two potentially positive scenarios ahead for the animated studio founded by movie mogul Jeffrey Katzenberg that it "becomes an acquisition candidate." The other was that the average box office performance of its upcoming slate of films beats expectations.

Both, however, are thought by sources to be long shots.

"The film lineup looks poor at best," said BTIG analyst Richard Greenfield, who has a sell rating on the studio's stock and says it is worth $15.50 per share.

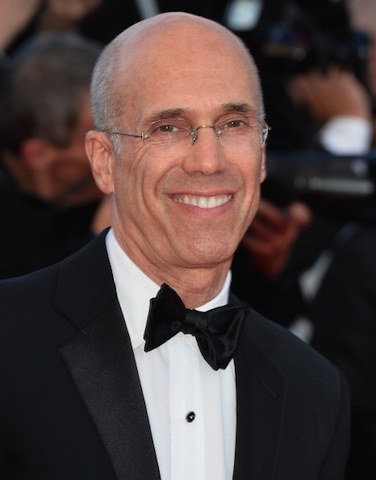

For the first time in his 40-year movie career, Katzenberg's performance is being seriously questioned by both Wall Street analysts and Hollywood peers. As an independent studio not tethered to a larger organization in the cost-heavy field of animated movies, his studio is overly dependent on the box office performance of individual films to meet its financial targets. Further, DreamWorks Animation's business model of only producing two to three movies per year has suffered from the dual realities of increased competition in family films and an overall downward trend in attendance at the domestic box office. These factor have resulted in a confluence of negative events recently, ranging from missed earnings to losses on poorly performing films to a U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission investigation into the write-down of film inventories the studio took on the movie Turbo in February 2014, have raised questions about DreamWorks Animation's future. (The studio is cooperating with the SEC investigation.)

Yet DreamWorks Animation shares are currently trading significantly higher than Greenfield's target, closing trading Tuesday at $23.99, primarily buoyed in recent weeks by a short-lived rumor that Japan's SoftBank was in talks to buy the studio for $3.4 billion. The rumor was fueled, in part, by one of Hollywood's worst-kept secrets: Katzenberg has been trying to sell DreamWorks Animation for years.

A DreamWorks Animation representative declined to comment or make Katzenberg available for an interview for this story.

Katzenberg isn't trying to sell his studio because he needs the money — he's among the richest men in the world with a net worth somewhere between $860 million and $957 million depending on who is doing the calculating. His goal has always been to use a sale of the studio to leverage himself into a bigger job at a larger organization — and get out from under the glare of Wall Street.

The now derailed talks with Softbank dovetailed nicely with that objective. The Japanese telecommunications and internet giant, newly flush with billions of dollars from the Alibaba IPO, is by all accounts looking to spend its way into Hollywood. Its initial interest in DreamWorks Animation likely stemmed from the fact that animated movies, unlike comedies or dramas, play well to an international audience, and DreamWorks Animation's just happen to perform especially strong in Asian markets.

But multiple sources told BuzzFeed News that Softbank soon realized that, as one Hollywood executive who requested anonymity for fear of damaging relationships put it, "when you dig into the cost structure versus revenue and profits you see that [the studio's] business model doesn't make a lot of sense."

Katzenberg began his film career at Paramount Pictures before moving on to Walt Disney Studios, where he had a spectacular decade-long run that included overseeing such animated classics as The Little Mermaid, Aladdin, The Lion King, and Beauty and the Beast, the first animated movie to receive a Best Picture nomination. He left Disney in 1994 after a falling out with then-CEO Michael Eisner and went on to found DreamWorks with partners David Geffen and Steven Spielberg.

In 2004, with the blessing of Geffen and Spielberg, Katzenberg spun out DreamWorks Animation and took it public on the strength of his reputation and the then-budding Shrek franchise.

But independent film studios are only as valuable as their most recent hit, which is why there are so few of them, particularly on the public markets. Hollywood and Wall Street have always had trouble understanding each other mainly because the former is a highly volatile hits-driven business while the latter likes stable companies with reliable earnings growth and cash flow generation. The disconnect is magnified for DreamWorks Animation since it produces just two or at most three films per year.

As a second movie studio executive who also requested anonymity said, "When you only make two movies a year, you better make sure one of them isn't a flop otherwise you're in trouble."

Since 2012, however, DreamWorks Animation has had to record a total of $157.5 million in losses on three movies — Rise of the Guardians, Mr. Peabody and Sherman, and Turbo. While the amount of the write-downs isn't large by movie industry standards — Disney took a $200 million loss on John Carter alone in 2012 — they have resulted in extremely volatile swings in the studio's stock price and earnings because its business model is tilted so heavily toward the box office performance of its films. For the full year 2013, for instance, DreamWorks Animation recorded a profit of $55 million, while for 2012 it posted a loss of $36.4 million.

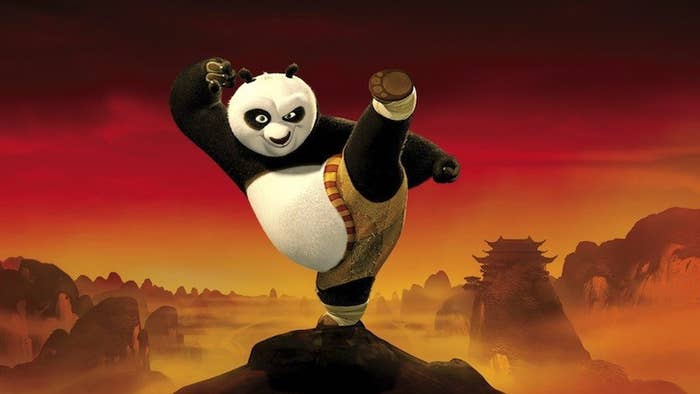

Unlike bigger media conglomerates such as Time Warner or Disney, DreamWorks Animation lacks cable networks to help offset box office misses. Its library of movies, which studios rely on to provide a steady source of revenue through DVD sales, licensing for video-on-demand, streaming, and syndication, is small by industry standards, featuring less than 30 films in total, with just a handful of them like Shrek or Kung Fu Panda hits whose rights can be sold in perpetuity. (Libraries need hits after all, since no one wants to license a movie nobody wants to watch.) By comparison, Warner Bros.' film library ranks as the world's largest, with the rights to around 6,500 movies, among them franchises like Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings that will be in demand among audiences for decades to come and will provide the studio with a lucrative annuity.

Further, animated movies are among the most expensive to make, with historic budgets for DreamWorks Animation's films averaging around $145 million. The studio also uses 20th Century Fox to distribute its films, paying that studio an 8% fee to do so. And DreamWorks Animation is rare among animation studios in that its movies are made almost entirely in-house.

A source close to DreamWorks Animation said that the studio "takes pride" in the fact that it makes its movie in-house and that it believes it "distinguishes them and the movies they make." But to Wall Street analysts and, more importantly, potential buyers, that simply means high overhead costs for staffing — the studio had 2,200 employees as of Dec. 31, 2013. By comparison, Lions Gate Entertainment, another independent publicly traded studio, has 650 full-time employees.

The reason Katzenberg wants to sell DreamWorks Animation is best crystalized in the view Wall Street has of the studio's ability to create franchises and its efforts to diversify its business and bring costs in line.

Released in June, for instance, How to Train Your Dragon 2 has so far grossed $613.5 million at the worldwide box office, according to figures compiled by Boxofficemojo.com, $176 million of that coming domestically, good enough to rank as the 12th highest-grossing film in the U.S. so far this year. The sequel's performance improved significantly on the $495 million worldwide box office gross of the original and a third installment is scheduled for 2017.

Based on the box office results, How to Train Your Dragon can rightly be considered a franchise, giving DreamWorks Animation its fourth in a decade, joining Shrek ($3 billion in worldwide gross over four films), Kung Fu Panda ($1.3 billion in worldwide gross over two films, with a third on the way next year), and Madagascar ($1.9 billion in worldwide gross over three films, with two more on the way between this year and 2018). Combined, these four franchises have grossed $7.3 billion at the worldwide box office for DreamWorks Animation.

Yet, this isn't enough for Wall Street, in part because profitability for each film has been squeezed.

"At the level of box office their films averaged five to seven years ago they would be quite profitable. However more recently they have averaged barely better than break even per film," said Creutz. "They really need better film performance. If they had more hits they would have more sequelable franchises."

Creutz, Greenfield and others are not optimistic, for instance, that Home and B.O.O, two of DreamWorks Animation's next three films, have franchise potential. Of course, even with the most sophisticated financial modeling techniques, predicting a given movie's box office performance is an inexact science — a surprise hit like Superbad comes out of nowhere seemingly every year, as does a massive flop such as After Earth.

In an effort to increase profitability, DreamWorks Animation has begun utilizing new technology and taken other measures to decrease the average cost per film by $20 million to $125 million.

"Our objective is to ensure that our box office successes will be more lucrative, and in the case where a film performs below expectations, that it can still be profitable," said DreamWorks Animation president Ann Daly on the studio's first-quarter earnings call about the production budget reduction.

At the same time, Katzenberg has aggressively made acquisitions such as the $155 million purchase of Classic Media, owner of the Casper and Lassie titles, in 2012 to expand its library and moved the studio into new business lines to lessen its earnings dependence on box office performance. He kicked off a trend of big media companies acquiring popular YouTube networks in May 2013 with the $33 million deal for AwesomenessTV. He expanded DreamWorks Animation's television production via a deal with Netflix to provide around 300 hours of original programming over the next few years. He's also hired new leaders for the studio's consumer products and TV division and launched a publishing unit.

While these bets may eventually pay off, they've also resulted in a $400 million increase in DreamWorks Animation's debt load and a decline of its cash on hand to $32 million as of the end of the second quarter.

In the jaded worlds of Hollywood and Wall Street, Katzenberg's moves are not viewed as a way to solidify DreamWorks Animation's business prospects, but rather as a means to better position it for a sale. Sources BuzzFeed News spoke to for this story — ranging from Wall Street analysts to Hollywood executives to those close to the studio — said that Katzenberg is desperate to do some kind of deal.

"He's looking to sell first and for cash second," the first Hollywood executive said of Katzenberg's game plan.

The problem Katzenberg faces in trying to sell DreamWorks Animation is basically one of saturation. When DreamWorks Animation went public in 2004, its only real competition was from Disney and Pixar. Now, however, not only does every major studio compete in animation, but many also have developed franchises of their own, from 20th Century Fox's Ice Age to Universal's Despicable Me.

According to a story in last week's Hollywood Reporter, Katzenberg may have personally sabotaged the deal with Softbank by trying to leverage it into a richer offer from Rupert Murdoch's 21st Century Fox.

If true, such a brazen move by a CEO, combined with the studio's recent earnings misses and an SEC investigation tied to its write-down of film inventories on Turbo in February 2014, could potentially attract activist hedge fund investors into the stock. But Katzenberg's voting control of DreamWorks Animation via its dual class share structure permits him to exercise such singular authority over the studio. And activist aggression in Hollywood hasn't worked so well in the recent past: Sony, which doesn't have a controlling shareholder, swiftly beat back an activist attempt by Third Point's Dan Loeb to divide its entertainment and electronics assets last year.

Though Softbank struck a deal to invest $250 million in Legendary Entertainment, no one believes that deal puts an end to its ambitions in Hollywood. Softbank, which recently bought a 70% stake in Sprint, didn't hire Nikesh Arora, Google's former chief business officer, to lead its global internet operation to stop with a small investment in Legendary.

The basic logic underlying Softbank's interest in DreamWorks Animation is that unlike comedies or dramas, animated movies and superhero films often perform magnitudes better at the overseas box office than they do domestically. And DreamWorks Animation's movies have done particularly well in Asia markets — at $65.1 million, China represented the largest international market for How to Train Your Dragon 2, which generated 71% of its total box office revenue abroad.

A source familiar with the situation said that Softbank was less interested in DreamWorks Animation's actual production capabilities and more interested in Katzenberg's connections and pairing him with Arora to go on a dealmaking spree in digital, television, and movies. But this source and others said Softbank is no longer talking to DreamWorks Animation in part because of Katzenberg's maneuvering. One source described Katzenberg's attempt at a bidding war as "old Hollywood" and said Softbank is looking to "new Hollywood" for deals now.

Softbank did not return an email sent through its corporate website for comment. Bankers at Raine Group, which advised Softbank on its Legendary deal, did not return multiple calls and emails for comment.

This could all be standard Hollywood chest thumping, of course, and a deal between Softbank and DreamWorks Animation could eventually be revived. In fact, it may end up saving the company tens of millions if not billions of dollars to wait and see how the upcoming films on DreamWorks Animation's slate perform.

"Why buy now for any strategic, it will only get cheaper," Greenfield said, a reference to the fact that if the studio's upcoming releases starting with next month's The Penguins of Madagascar don't meet expectations DreamWorks Animation's stock will decline making it less expensive to acquire.

Absent an acquisition, the question of whether the studio should even be a public company still remains. Observers say its small release slate, reliance on film performance to drive growth, lack of assets to offset underperforming movies, and share structure that allows Katzenberg free operating reign all conspire to make DreamWorks Animation an ideal candidate to take private.

"Jeffrey is committed to running the company in a way that is best for the company and that changes over time," said the source close to the studio without elaborating.

This much is clear: Katzenberg will have a lot to answer for on the studio's third-quarter earnings call on Oct. 29. It should be pretty animated.

Correction: This post has been changed to reflect that the SEC investigation is into the write-down of film inventory DreamWorks Animation took on the movie Turbo in February 2014. A previous version misstated that the investigation was tied to the timing of a stock sale by Jeffrey Katzenberg.