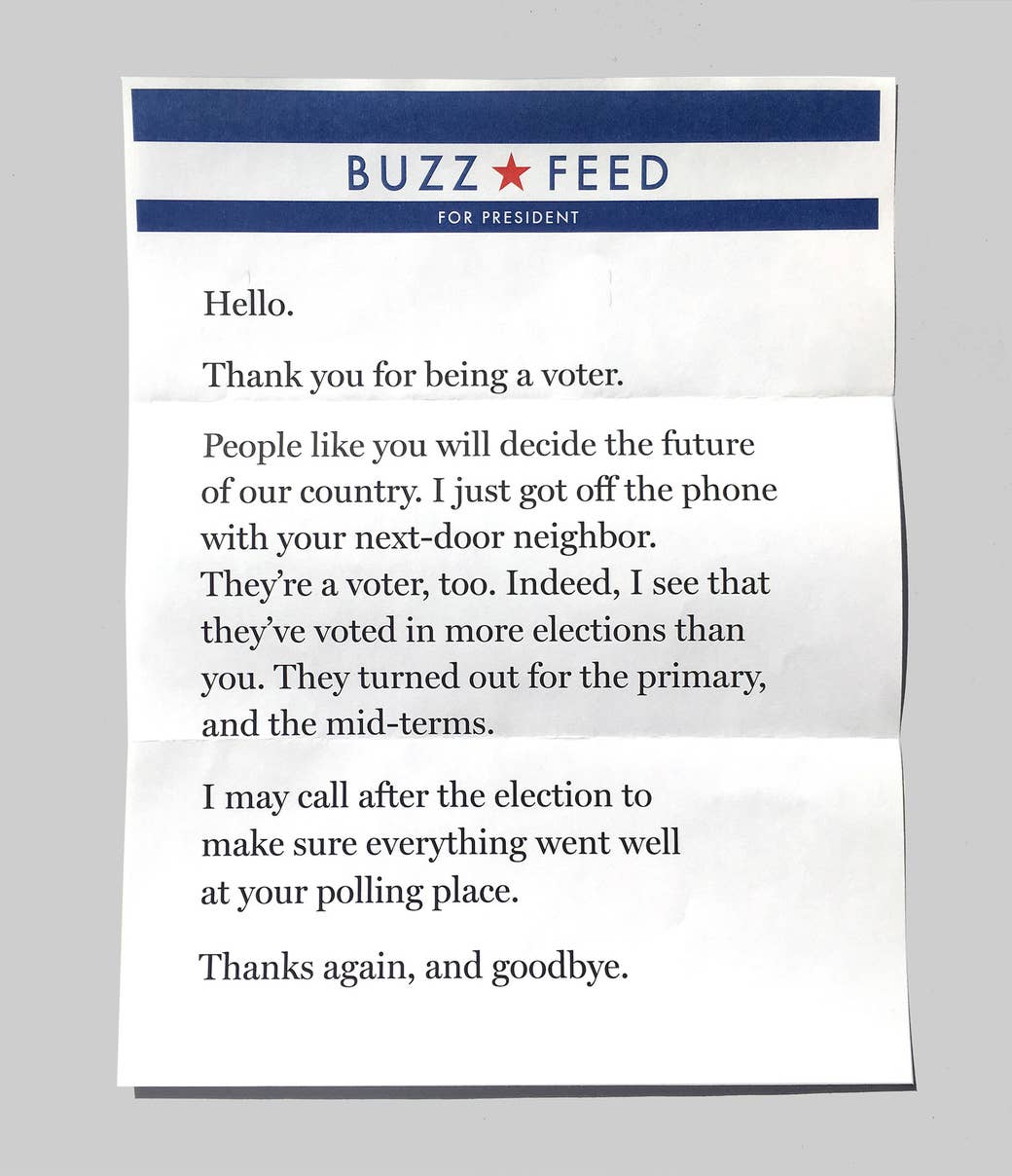

This message, which could be used in a mailing, or in a script for a phone canvasser, is packed with phrases that have been shown in scientific experiments to nudge people into voting. Here’s why these words can convince voters to get out to the polls.

1. We don’t like being shown up by our friends and neighbors.

Voting may be a civic duty, but getting people to do the right thing can be tough. That’s why political operatives were blown away in 2008, when a team led by political scientists at Yale University revealed how to ratchet up the social pressure to get people out to the polls. Before the 2006 primary elections in Michigan, the researchers mailed 80,000 households telling them: “Do your civic duty — vote!”

By itself, this message boosted turnout from 29.7% to 31.5% — hardly a game-changer. But when the mailings also described the past voting records of members of the household and their neighbors, and said that updated information would be mailed after the election, turnout shot up to 37.8%.

Compared to actually talking to potential voters, mailings are usually ineffective. But this boost in turnout beat the typical bump provided by phone calls and rivaled the effects face-to-face canvassing. Although we may think of ourselves as independent, it turns out that we like to be seen as part of the virtuous crowd.

The key phrase is “be seen,” which is why our optimized message contains a subtle reminder that voting records are public, and includes the suggestion that you’ll get a call after the election to ask about your voting experience.

In an experiment published in April, researchers led by Todd Rogers of Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government sent a get-out-the-vote letter to more than 770,000 potential voters in 29 battleground districts in the 2010 congressional elections. The version that included the wording about a post-election follow-up call was the most successful in boosting turnout.

2. And that social pressure can be contagious.

Nowadays, pressure to vote doesn’t just come through the mailbox — it can also happen on social media. During the 2010 congressional elections, Facebook ran a massive experiment in which more than 60 million users received a message in their News Feed encouraging them to vote, providing a link to find polling places, and including a button to announce to their friends that “I Voted.” The message also revealed the pictures of up to six of their friends who had clicked the same button.

Because some people might have clicked the button without voting, Facebook later compared the actual voting records of those who received the message to users who didn’t see it. Those who got the message were more likely to vote, and clicking the “I Voted” button also seemed to influence their closest friends.

The effects were small, but on such a huge platform the numbers stacked up. Overall, Facebook estimated that the message itself nudged about 60,000 people who received it into voting, while a further 280,000 people were triggered to vote as the “I Voted” ripples spread from friend to friend.

3. But don’t overdo it. (Looking at you, Ted Cruz.)

While social pressure definitely works, there’s a potential downside: Sending mailers comparing people’s voting records to those of their neighbors can creep them out.

For campaign operatives, that poses a dilemma. Unlike academic political scientists, who run non-partisan experiments, campaigns have to worry about whether their candidate will be perceived as manipulative and hectoring. For them, a message that sends people to the polls determined to vote for a rival is the worst possible result.

“Heavy-handed social messages have the potential to backfire,” Costas Panagopoulos, a political scientist at Fordham University in New York, told BuzzFeed News.

Most campaigns have steered away from piling on the social pressure. But not Ted Cruz, who before February’s Iowa caucuses sent out mailers that not only graded the voting records of recipients and their neighbors, but were styled to look like an official citation and marked “Voting Violation.”

@RBPundit

Many potential voters were outraged, and the tactic earned a strong rebuke from Iowa’s top elections official, Paul Pate. "Today I was shown a piece of literature from the Cruz for President campaign that misrepresents the role of my office, and worse, misrepresents Iowa election law," he posted on Facebook shortly before the caucus. “There is no such thing as an election violation related to frequency of voting.”

Still, some experts believe campaigns could exert more social pressure, without going the full Cruz and accusing people of spurious violations.

“Concerns from political campaigns might be overblown, and they might be leaving votes on the table,” David Nickerson, a political scientist at Temple University in Philadelphia, told BuzzFeed News by email.

4. Always say “thank you.”

Expressing gratitude, in contrast, carries no risk of turning people off. During the 2009 race that saw Chris Christie become the governor of New Jersey, Panagopoulos sent out non-partisan mailers to some 40,000 potential voters. Turnout among those who were thanked for voting in the past was 39.2%, 2.5 points higher than those who were not thanked.

“The effects are not as strong as for explicit social pressure, but they’re pretty strong,” Panagopoulos said.

In the past few years, similar messages of thanks for past voting have become a staple of campaign messages. There’s nothing to lose, and votes to gain, from being polite.

5. Try to make voters feel worthy.

Our optimized message contains the phrase “being a voter,” rather than than simply thanking people for voting. The idea of swapping a verb for a noun comes from research led by psychologist Christopher Bryan of the University of Chicago, who found that it boosted turnout among when delivered in an online survey to potential voters in the 2008 presidential election, and the 2009 race for New Jersey governor.

The message worked, the researchers suggested, because it linked voting to people’s sense of self, allowing those who subsequently voted to “assume the identity of a worthy person.”

But earlier this month, a team led by Alan Gerber of Yale University published a larger contradictory study, contacting voters by telephone before the 2014 primary elections in Michigan, Missouri, and Tennessee. It found no significant boost in turnout from including the “voter” wording in the phone script.

So the jury is still out on this one. But Gerber told BuzzFeed News that he sees no potential for a backlash in describing people as voters, and some political operatives’ are already framing their messages in this way. For example, instructions to canvassers working for Bernie Sanders in the Florida primary contained the following script, to be said to people who described themselves as supporters or leaning toward the candidate:

“Thank you for being a voter for Tuesday! We are calling voters all across the state and while it looks like turnout is going to be high, the race is close and your vote could be the one that makes the difference.”

6. But don’t pander (especially if you’re not sure who you’re talking to).

In the run-up to the 2000 presidential election, an article in The New Republic raised the curtain on campaign data mining, noting that politicians “know not just your name, address, and voting history but also your age and the age of your children, whether you smoke cigars, where you shop, where you attend church, what kind of car you drive, how old it is, whether you’re on a diet, and what type of pet you have.”

That’s true. Democratic Party operatives, for instance, use data from a company called Catalist that contains up to 700 different data points on each potential voter. From a small sample of people whose opinions have been surveyed, the theory goes, it’s possible to predict the views of everybody else.

Welcome to political “microtargeting,” in which the electorate is sliced and diced into groups that can be sent different messages to reflect their predicted passion for gun rights, environmental protection, and so on. Increasingly, these messages are being delivered not just by mail or phone, but as targeted ads on Google and Facebook.

But microtargeting may have been oversold. During the 2012 election cycle, Eitan Hersh of Yale University gained access to the Democratic Party’s data sources and surveyed operatives to find out how it was used. He concluded that detailed consumer data added little to the information available through public records — such as party registration, voting history, gender, and (in some states) race.

According to Nickerson, two additional pieces of personal information are valuable: education level, which helps predict how people will vote, and telephone numbers, which are crucial to making contact. “Pretty much everything else is just hype,” he said. And Nickerson should know: In 2012, he was director of experiments for the Obama campaign’s data analytics team — seen as the most sophisticated in political history.

Targeted messages can also backfire. In experiments run in 2010 and 2011, Hersh sent a sample of potential voters a mailing about a fake political candidate called Williams. The letters either made general pledges that Williams would work on voters’ behalf, or more specific promises to help groups such as born-again Christians or Latinos.

Participants were then asked whether they were likely to vote for the candidate, on a scale of 0 to 100. The targeted messages had only modest effects when sent to members of the intended group (such as born-again Christians or Latinos). But when they were misdirected, they drove support down by 20 points or more.

“People hate being mistargeted,” Hersh told BuzzFeed News.

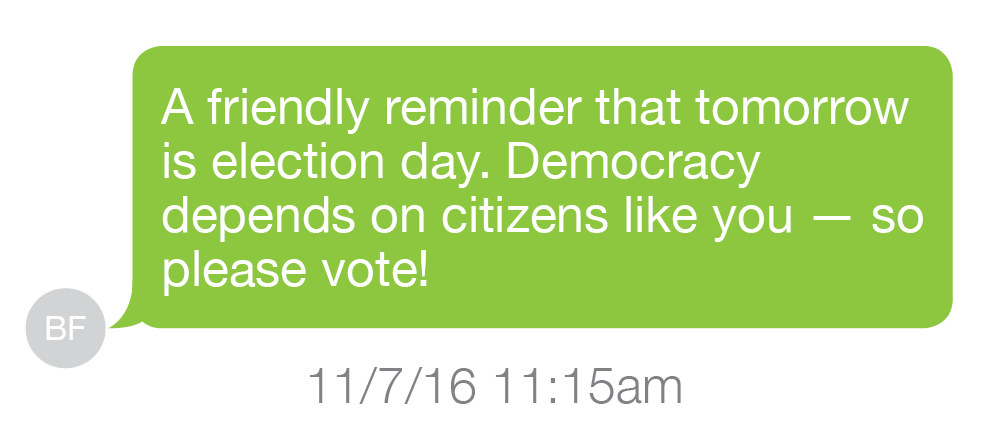

7. And just before election day, send a reminder.

Emails seem to be ineffective, unless they come from public officials. But text messages seem harder to ignore. In 2010 primary elections in California, including the race for governor, researchers sent the message above to the cell phones of more than 14,000 voters. It boosted turnout from 8.9% to 9.8%.