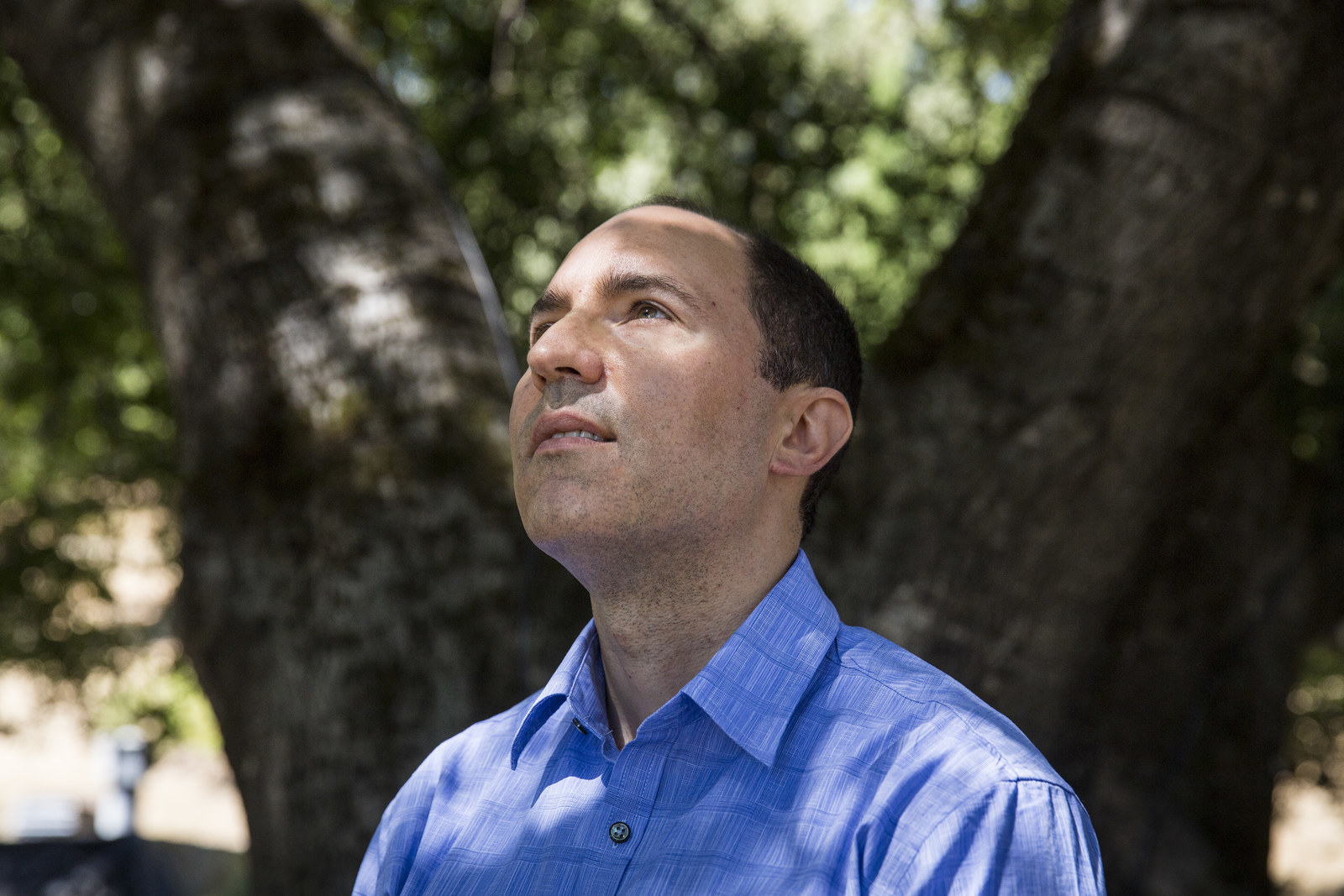

Brandon Staglin lost touch with reality in the summer of 1990, after his freshman year of college. His first serious relationship had just broken down. Back home in Walnut Creek, California, he was struggling to find a summer job.

That’s when the voices became impossible to ignore. “Baby Brandon!” they taunted. “Mixed-up kid!”

Staglin couldn’t sleep and thought that a wall had come down inside his head, leaving the right side hollow. “I felt I’d lost half of my spirit,” Staglin told BuzzFeed News. So he covered his right eye with his hand, fearful that a new personality would fill the void if he let any experiences in.

Delusional thinking like this, often accompanied by voices and other hallucinations, is a classic symptom of the psychosis that grips people with schizophrenia.

Travis Webster’s lowest ebb also came when he was 18, back in 2013. Diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, which combines psychosis with wild mood swings, he’d stopped taking his medication. That led to a conflict with his parents: Webster thought they were conspiring against him, despite their efforts to help. He was filling out a restraining order against his family when two police officers and a social worker knocked on his door in downtown San Diego.

Things quickly got out of hand, as the former high school water polo player resisted the officers’ attempts to restrain him. “I am 6-foot-5, 220 pounds,” Webster told BuzzFeed News. “The cops were so small.” He punched one of them in the face and was sentenced to two months in the county jail.

Life has gotten better for both Staglin and Webster. Today, their psychosis is controlled by medication, and they’ve become advocates for mental health: Staglin helps run the One Mind Institute, a research organization set up by his family, and Webster speaks about his experiences in schools.

But silencing the voices and banishing delusions doesn’t mean that everything is OK. Once high-flying students, both men’s grades went into free fall when they were gripped by psychosis. And even after those symptoms were under control, they found it hard to concentrate on their studies.

Hallucinations and delusions may be the public face of schizophrenia, but the hidden cognitive symptoms — which include difficulty focusing on mental tasks, understanding speech, and remembering what just happened — make it very hard for people with the condition to live satisfying, productive lives.

“They might hear voices and learn not to respond to them,” Cameron Carter of the University of California, Davis, a specialist in the cognitive aspects of schizophrenia, told BuzzFeed News. But it’s hard to follow people’s conversations if you literally can’t process what they’re saying. And there’s no compensating for an inability to concentrate.

Staglin and Webster, together with dozens of other volunteers, have found some relief, however, by playing computer games designed to strengthen their mental abilities. They have participated in trials led by Sophia Vinogradov and her colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), which draw from research into “neuroplasticity” — the idea that the brain changes in response to how it is used. This means that neural circuits can be strengthened through mental training, much like an athlete builds muscle by pumping iron at the gym.

The games are designed by a company called Posit Science, launched by one of the pioneers of neuroplasticity, Michael Merzenich, also at UCSF. They automatically adjust their difficulty so that players succeed on only around 80% of the tasks. Improve your performance, and the game gets harder. If your concentration slips, the tasks get a little easier until you’re back in the groove.

It’s like having a personal trainer in the gym, keeping you in just the right zone to build strength and fitness, without slacking or overtraining. And like a physical fitness regime, improvement only comes with persistence — Vinogradov’s experiments typically involve up to 50 hours of training, given over 8 to 10 weeks.

“If you don’t do it intensively, you’re not going to get the same results,” Vinogradov told BuzzFeed News. “You need to come back every three days, and do your reps again.”

After his first psychotic episode, Staglin returned to his classes at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, but his grades plummeted. He was eventually able to drag them back up, but only by isolating himself socially to devote his mental energy to his studies. Reading was an effort. He felt socially awkward and struggled to make friends.

After college, Staglin worked for a satellite engineering company in Palo Alto, California, and was applying to grad school at MIT when the pressure became too much again. “I had to resign from my job. I couldn’t focus. I couldn’t concentrate,” Staglin said.

It wasn’t until the late 1990s that Staglin took part in some of Vinogradov’s earliest experiments, which were designed to help people with schizophrenia make sense of speech and other sounds. Among other tasks, he had to tell whether a rapidly played tone was rising or falling in pitch. Staglin diligently did his reps and saw some benefits after many years of struggling with the cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia.

Up or Down?

In one training exercise, volunteers must recognize whether tones are rising or falling in pitch.

For Staglin, realizing that he was getting better at the games boosted his confidence. As his performance improved, he became more outgoing. “I think it’s because of the cognitive benefits of being able to perceive and understand conversations better,” he said.

Despite the initial experiment's benefits to Staglin and other volunteers, it took several years to win funding for the work. In their first major study, published in 2009, Vinogradov’s team invited people with schizophrenia to visit their lab and play a variety of games to improve how they understood sounds. As well as distinguishing the rising or falling tones, they also had to distinguish between distorted syllables containing similar sounds, such as “pag” and “bag,” and were given more complex tasks including remembering details from conversations played on the screen.

Pay Attention

People with schizophrenia often struggle to follow conversations, but practice can help.

The volunteers who’d trained on these tasks subsequently took tests in which they had to recall words. They performed better than a control group who had trained on computer puzzle games. They also did better on general tests of cognitive ability. Encouragingly, the gains were about twice as large as those typically reported in previous cognitive training studies. And the benefits could still be seen six months later.

Since this initial success, Vinogradov and her colleagues have experimented with different training games, some targeting brain circuits that process social information — for example, by asking volunteers to read the emotions on pictures of people’s faces. The researchers have also tried to intervene earlier in the disorder. (Like Staglin and Webster, most people with schizophrenia experience their first psychotic episode as young adults.)

Last year at the International Congress on Schizophrenia Research in Colorado Springs, Vinogradov’s team reported that the training did more than boost the cognitive abilities of recently diagnosed young people: It also seemed to reduce the severity of their psychotic symptoms, measured six months later.

That doesn’t mean that brain training can replace the drugs that keep hallucinations and delusions at bay. But it suggests that the games may help to protect the brain from the disrupted wiring that is thought to be the root cause of schizophrenia’s symptoms.

The researchers want to turn the cognitive improvements into real life-changers, but it’s not yet clear whether the training can make a big difference to holding down a job and building friendships. Vinogradov thinks this may require combining the computer games with other treatments, such as occupational therapy to help people with schizophrenia manage everyday tasks, and low doses of stimulant drugs that can improve focus.

Webster got involved in Vinogradov’s research last year, volunteering for a study to see whether the training would work on an iPad — so that young people with schizophrenia can give their brains a workout at home.

Like Staglin, Webster had struggled with mental tasks and felt socially isolated. These problems were compounded, he said, by several concussions during his time in jail, when he was beaten by fellow inmates. Unfamiliar with the jail’s unspoken rules, he first got into trouble by sitting in a part of the canteen claimed by black prisoners.

After his release, Webster found it difficult to resume his studies. “I would do homework and I would feel that I had to get up and stop and go listen to music or something,” Webster said. Trying to keep working wasn’t a good idea, he found: “I get extremely frustrated when I’m in that state. I’ll start slamming doors and stuff, and throwing things across the room.”

Webster felt that the iPad training helped. “I started noticing that I was less anxious when I was in public,” he said. “My thoughts became less disorganized.”

Games designed to help a patient understand what they are seeing, in particular, seemed to boost his peripheral vision, increasing his awareness while driving. And his mom noticed that he responded more quickly when they talked — previously, their conversations had been punctuated by long pauses.

Still, Webster would often quit the games before he was supposed to, because he found the exercises boring. “I was supposed to do five hours a week. I ended up doing three,” he said. “With schizophrenia, it’s really common to have a lack of motivation.”

Cameron of UC Davis, who has collaborated with Vinogradov’s group, believes that the computer games industry — masters of cliff-hangers and cinematic thrills — should be able to solve that problem.

Vinogradov’s team is now concentrating on intervening even earlier, in young people who haven’t experienced a full-blown psychotic episode but are starting to behave oddly or having trouble distinguishing dreams from reality. The researchers have already shown that the training helps young people rated at high risk of developing psychosis get better at remembering words.

But the idea of starting treatment before people have experienced a psychotic break is controversial. “Attenuated psychosis syndrome,” intended to describe people at risk of schizophrenia, was rejected as a new psychiatric diagnosis in 2012. Critics argued that more than 70% of young people who have strange thoughts and minor hallucinations do not go on to develop schizophrenia. If this diagnosis became mainstream, they worried, it could lead to a massive and unwarranted expansion in the prescription of powerful antipsychotic drugs.

Getting young people to play computer games doesn’t arouse quite the same fears. “Cognitive training is probably benign enough,” Allen Frances of Duke University, who led the opposition to the proposed diagnosis, told BuzzFeed News by email. But he remains worried about young people who may never develop schizophrenia being stigmatized by an "at risk" label.

Webster would have welcomed the opportunity to seek early treatment. He began to have problems concentrating from the age of 14, and found it hard to socialize with other kids.

“I think my life would have different," he said, "if they’d caught this disease before I had a full-blown episode."