Six people are dead as fire rages around the city of Redding, California. The iconic Yosemite Valley has been deserted, shrouded in smoke. After the devastating wildfires of 2017, which razed more than 10,000 buildings and killed 43 people, 2018 is shaping up to be another bad year for fires in the Golden State.

It’s easy to simply blame climate change — and warmer, drier conditions are definitely a big factor in a trend toward larger fires in recent years. But experts studying California’s fires say that the state’s burgeoning population and its sprawl into areas that were once wild have helped create a perfect firestorm.

“There is a clear human influence on fire patterns,” Alexandra Syphard, an ecologist with the Conservation Biology Institute, based in San Diego, told BuzzFeed News.

Studies by Syphard and others show that the risks of wildfire increase when housing is built in rural areas that used to be able to burn without threatening lives and property. This rural sprawl has been massive in California, as the state’s population has almost quadrupled since 1950. But people haven’t just placed themselves in the line of fire: They’re also causing most of the blazes that wreak such havoc.

Across most of California, human activities and infrastructure — including campfires, arson, electrical equipment and vehicles, and power lines — start the vast majority of fires. That is creating a big headache as the state’s leaders wrestle with how to protect people and property from the flames.

“Even if we can reverse climate change, that’s going to take decades,” Lynne Tolmachoff, a spokesperson for the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, or Cal Fire, told BuzzFeed News. “This is something we have to deal with right now.”

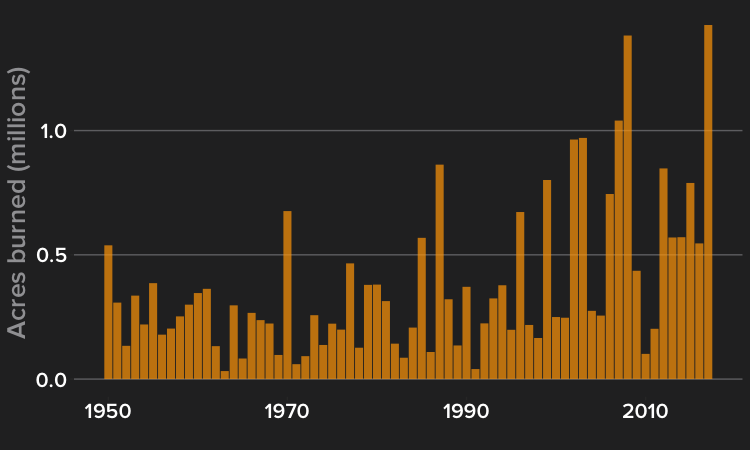

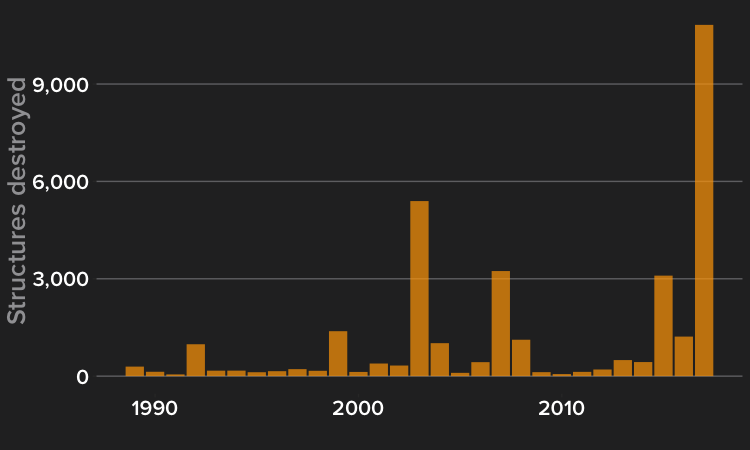

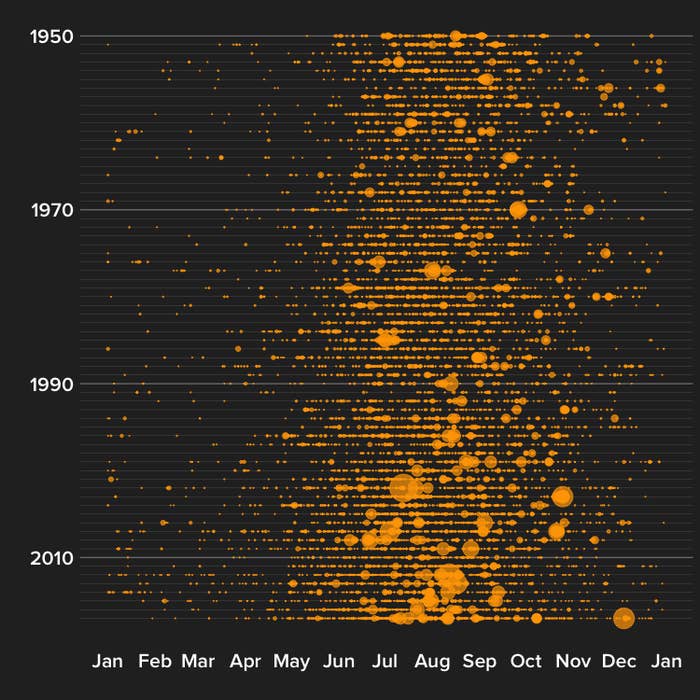

A BuzzFeed News visualization of California fires from 1950 to 2017 shows that larger fires have become more frequent and the fire season has expanded — particularly for human-caused fires.

Big fires have gotten more common.

Most of California’s rain and snow falls in between October and March, which means that fire season peaks in the summer, as vegetation dies and dries out. In Southern California, the season extends into the fall, when Santa Ana winds, which blow from the dry interior toward the coast, whip up small fires into major conflagrations.

As the state has dried and warmed, the fire season has started earlier and larger areas have burned. Similar changes have occurred across the western US.

But the pattern is different for natural and human-started fires.

Before people dominated the landscape, almost all wildfires were started by lightning. Cal Fire’s data shows that these natural fires have become larger in recent years — exactly what scientists would expect to see with climate change.

The severe drought that parched the state between 2011 and 2017 made matters worse. In California’s dried-out forests, at least 129 million trees have died, many killed by bark beetles, creating a tinderbox of dead timber.

But human-caused fires have done most to extend California’s fire season. They include the massive Thomas Fire, which raged around Santa Barbara in December 2017, destroying more than 1,000 buildings and killing 21 people. It is now the subject of lawsuits from residents who blame the electricity utility company Southern California Edison for the blaze.

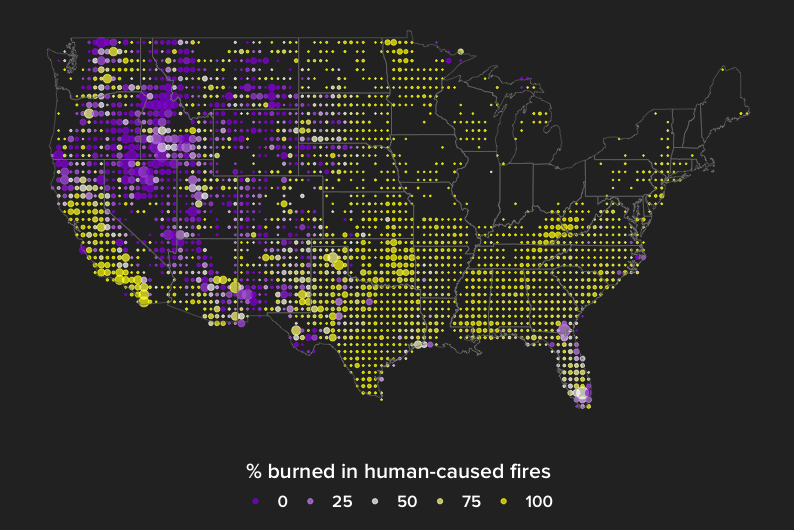

California’s problems with human-caused fires set it apart from most of the West.

Climate change is increasing the severity of wildfires across the western US. But in the sparsely populated Mountain States, natural fires still dominate. Most of California, on this map, looks more like the US east of the Rockies, where human-caused fires have also expanded the fire season.

“We’re overwhelming the natural ignitions,” Bethany Bradley, an ecologist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, told BuzzFeed News.

East of the Rockies, human-caused fires happen most often when people burn yard waste and the fires get out of control, Bradley said. That creates an opportunity to tackle the problem by imposing restrictions on burning when conditions become too risky. But California’s fires have a more diverse range of human causes, making it harder to reduce the risk.

One paradox is that in California, and across the nation, the number of fires has gone down even as the area burned has increased. (In part, that may reflect the fact that fewer people are smoking and causing fires with discarded butts and matches.)

“It’s not the number of ignitions that’s most important; it’s the timing and location,” Syphard said. Reducing the risk, she warned, will require a range of measures, including policies to limit rural sprawl.

Syphard and her colleagues are now trying to identify the sources of ignition that trigger the most damaging human-caused fires. “One of those, for sure, is power lines,” she said.

Power lines pose a particular hazard in high winds, when they can be brought down or come into contact with nearby trees. Cal Fire has blamed power lines for 12 of the fires that devastated Northern California in October 2017. (The cause of the Tubbs Fire, which raced into the suburbs of Santa Rosa on Oct. 10, killing 22 people, is still under investigation.)

But reducing the risk from power lines is hard. Putting them underground costs more than twice as much as hanging them from poles; the costs of replacing existing overhead lines across the state could run to hundreds of billions of dollars.

Utilities, meanwhile, are getting jumpy about their liability. Pacific Gas & Electric, which provides power across Northern California, announced in June that it may temporarily shut down the grid in areas threatened by extreme fire hazard. San Diego Gas & Electric in the far south of the state actually did pull the plug on 12,000 customers last December as Santa Ana winds raged.

That isn’t popular. “People don’t want their power shut down,” Cal Fire’s Tolmachoff said.

But if California can’t reduce the number of catastrophic fires, last year’s record season may become the new normal.