“Can you get me tickets for Hamilton?” Abbi Fox, until recently a realtor selling swanky homes in Marin County, north of San Francisco, knows how to break the ice.

Her opening gambit instantly dissolved any tension about talking over what for months she dodged discussing with even her closest friends. Abbi had known that something was wrong when her memory started to fail. Today she has been diagnosed with a condition called mild cognitive impairment, and is enrolled in a clinical trial of a drug for Alzheimer's disease. And that places Fox, 72, and her family on the front lines of the fight against the leading cause of dementia.

“Abbi didn’t want to talk about it with anyone,” explained her husband, Rob, when I met with the couple a few days later. He recalled fielding calls from anxious friends. “When she’s ready, she’ll talk about it,” he told them.

Abbi mustered the courage to send her friends an email explaining her condition a few months ago. “The reaction has just been amazing,” she said. “I happen to have an amazing group of lady friends. And my two daughters and my husband. They are all so supportive.”

She is in a clinical trial for aducanumab, being tested by the biotech firm Biogen of Cambridge, Massachusetts. The drug attacks a protein called amyloid-beta, which builds up in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease. This buildup is thought to trigger a cascade of problems that lead to dementia.

Aducanumab is one of a handful of experimental drugs that biomedical scientists hope will not just alleviate symptoms, but also slow the disease’s progress.

Days before BuzzFeed News first spoke with Abbi, however, another of these drugs — called solanezumab or “sola” — had hit the headlines, for the wrong reasons. “Eli Lilly’s Experimental Alzheimer’s Drug Fails in Large Trial,” wrote the New York Times.

News reports discussed what the failure meant for scientists’ understanding of Alzheimer’s, a disease that has proved far more complicated than once thought, and looked at the prospects for other drugs in the pipeline. Others framed the story as a huge business blow for the pharma giant Lilly — its shares lost 10% of their value overnight.

Few spoke about the families grappling with the erosion of their loved ones’ minds, or to the patients who have volunteered to take part in clinical trials. Yet without them, there will never be an effective treatment, however brilliant the scientists involved, and however determined Big Pharma is to find the next blockbuster drug.

Abbi’s diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment is described by the Mayo Clinic as an “intermediate stage between the expected cognitive decline of normal aging and the more-serious decline of dementia.” Not everyone who gets this diagnosis goes on to develop Alzheimer’s disease. But many, sadly, do.

Abbi is now a volunteer in the war against Alzheimer’s because of a sobering realization that doctors had in the last decade: By the time dementia sets in, the damage that has accumulated in the brain is at an advanced stage, and may be impossible to reverse. Scientists now think that the best hope of making a real difference lies in intervening early, as soon as problems start to emerge — or even before, for people with a family history of dementia that places them at high risk.

Abbi knew that something was wrong more than a year ago when she started struggling with the legal paperwork for her real estate deals. “I was not happy to give it up,” she said, sitting with Rob in their living room. “It was the definition of who I am.”

There was a weekly rhythm. Each Monday she would pull all the new ads and match listings to the requirements of her wealthy clients. Later in the week, she’d meet other realtors over lunch and shoot the breeze. Abbi knew that she couldn’t stay in the business. “These people were relying on me to buy $2 or $3 million homes,” she said. “I could screw it up for the person I’m buying for.”

Rob had already begun to notice that Abbi was having problems with her short-term memory — for example, repeatedly offering more vegetables when family or friends gathered for a meal.

As Rob explained about his wife’s symptoms, my mind flashed back to my initial telephone conversation with Abbi. During a brief pause, as I caught up with my note-taking, Abbi had stepped in to jog things along: “Can you get me tickets for Hamilton?”

“I wish that I could,” I quickly replied, not wanting her to notice that I’d been thrown by being asked the question again. (When we talked about it later, Abbi teared up, agreeing that the repetition was a symptom of her condition.)

Forced retirement was dispiriting enough, but Abbi’s first encounter with a medical specialist was devastating: “He was this rude, hideous man.” When Abbi mentioned that she wanted to take her two grandchildren to Paris, the doctor said, “You’d better hurry up and do it.”

“He had no bedside manner,” Rob observed.

When she got home after the consultation, Abbi was hyperventilating. Her youngest daughter, Marcy, said, “Mom, he’s an idiot.” So Abbi went back to her primary care doctor, and was referred to the Memory and Aging Center at the University of California, San Francisco, where she had a much better experience. Staff at the center broached the possibility of joining a clinical trial.

Abbi and Rob came home with reams of paperwork describing the clinical trials recruiting patients at the UCSF center — typically there are eight to ten trials enrolling at any time.

Some, like the Biogen trial that Abbi opted for, are massive “phase 3” trials running at dozens of medical centers worldwide. These are the make-or-break, final stage of testing, needed to show whether a drug actually works well enough to win approval from the Food and Drug Administration as a new treatment. (Eli Lilly’s disappointing announcement about sola came after it failed to meet its goals in another phase 3 trial.)

Patients learn the goals of the research before enrolling, and then are told to go away and digest the informed-consent documents at their leisure. “I call it the period of contemplation,” Mary Koestler, clinical trials coordinator at the UCSF Memory and Aging Center, told BuzzFeed News. Potential volunteers can’t be put under any pressure to take part — and are also free to withdraw from a trial at any point if they decide it’s not for them.

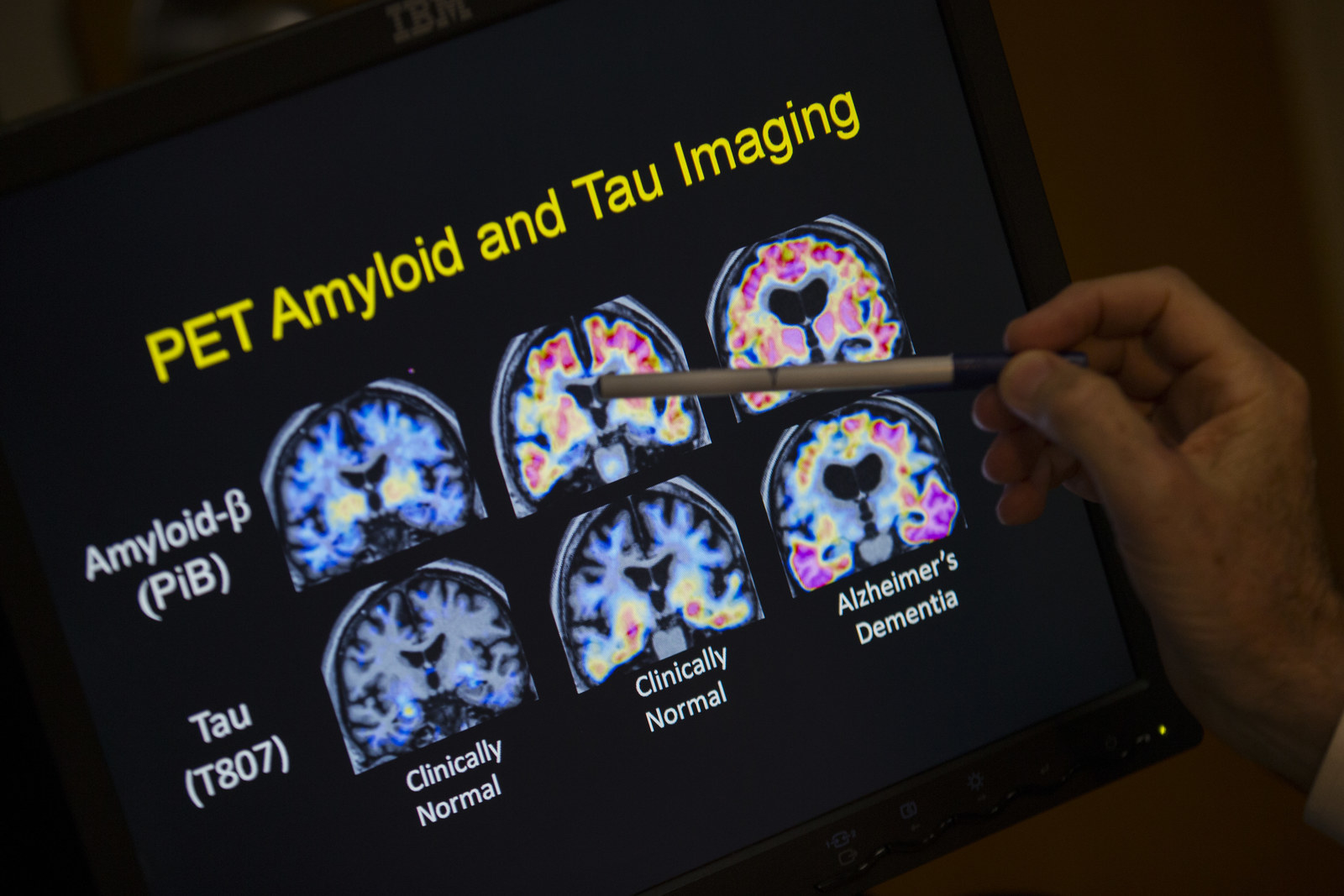

Even after volunteering to test an experimental Alzheimer’s drug, there’s no guarantee that you’ll be accepted. First come exhaustive cognitive and medical tests to make sure that patients meet the inclusion criteria. For Abbi, these included a spinal tap, an MRI, and a special type of PET scan that can actually detect amyloid-beta in the brain.

Abbi did meet the criteria, and now makes monthly visits to UCSF for a one-hour infusion of what might be aducanumab — or might be an inert placebo. Neither Abbi nor any of the clinical trials staff at UCSF are allowed to know whether she’s on the active drug, as part of the rigorous “double-blind” procedures required for phase 3 clinical trials.

While sola and aducanumab both target amyloid-beta, they work in different ways. Sola was supposed to mop up the protein from the blood, while aducanumab attacks “plaques” of amyloid-beta that build up in the brain. So there’s reason for optimism in that difference, despite sola’s failure: In August, a paper in the science journal Nature reported that aducanumab reduced amyloid-beta plaques in the brains of 165 patients in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. It also seemed to slow their cognitive decline — although there weren’t enough patients to make a statistically definitive judgment on that.

Now Biogen is running two phase 3 trials, which will involve 2,700 patients and bring the total cost of developing the drug, together with investment in manufacturing, to some $2.5 billion.

Drug development is a long haul. Results from Biogen’s phase 3 trials aren’t expected until 2020. If aducanumab disappoints, then hope will shift to drugs in earlier stages of development that target another brain protein called tau. In the brains of people with Alzheimer’s, tau forms tangles that are toxic to nerve cells.

Volunteers in Biogen’s trials must be watched closely. Despite the positive results so far, 27 of the patients in the trial published in August developed brain swelling, and 12 were taken off the drug. But Abbi has had no ill effects, and enjoys her trips to UCSF with Rob. “It’s our date day,” she said. “We get lunch.”

It’s the cognitive assessments, which must be given every few months to monitor her progress, that Abbi finds burdensome and somewhat humiliating. These involve pencil-and-paper tests and verbal tasks like counting backward in nines from 100. Many volunteers dislike the tests, Cynthia Barton, a nurse practitioner on the UCSF clinical trials team, told BuzzFeed News: “It’s not always easy to do two hours of cognitive testing that you’re not very good at anymore.”

Still, there are benefits to being enrolled in a clinical trial, not least the extended contact with nurses and doctors that isn’t part of everyday medical care. For patients with only basic medical insurance, that’s especially welcome. But for everyone, including caregivers like Rob, it eases the pressure.

“You can’t undervalue the burden that some caregivers are under,” Adam Boxer, a neurologist who heads the UCSF clinical trials team, told BuzzFeed News. “Not just the amount of time and physical effort they put into it, but just emotionally.”

For William and his wife Barbara — not their real names — the stigma associated with Alzheimer’s disease is such that they only agreed to be interviewed for this article on condition of anonymity. William, aged 68, is a retired surgeon who is also enrolled in one of Biogen’s aducanumab trials. As a former Army reservist in the Medical Corps, William said that he applies the military doctrine of “need to know” to his condition.

“I don’t need to stand on the rooftop and shout it to the neighborhood,” he told BuzzFeed News.

But William’s biggest concern is that going public might create problems for his younger family members. He was one of 12 siblings, and dementia runs in the family. All five sisters, and all but one brother, have been affected. William’s current diagnosis is mild cognitive impairment, but he is realistic about what probably lies ahead. “It has a high propensity to progress,” he said.

William has good reason to be worried about the consequences of revealing a family history of Alzheimer’s for relatives who are still at work. That’s usually where the earliest signs of the condition get noticed. A public diagnosis is often a career-ender, and no one wants to be under a spotlight, with their bosses looking for the first hints of mental decline.

Even if they aren’t looking for signs of dementia, human resources departments can create distress for employees beginning to experience symptoms. Barton, the UCSF nurse practitioner, said that patients can have the humiliating experience of being counseled for substance abuse — another common cause of sudden problems with job performance.

As a medical man, William went into the Biogen trial with his eyes wide open. “There are advantages and disadvantages to how much you know about something,” he said. While he holds hope that aducanumab may help him, he also knows that drugs can fail in clinical trials.

Abbi and Rob, meanwhile, hadn’t given much thought to the possibility, until the news about Lilly’s sola trial broke on Nov. 23. “It hit me really hard,” Rob said. “What if someday we get a phone call …”

In reality, that isn’t how these things work. Nobody in the sola trial got a call. Neither did Boxer, even though he was one of the senior doctors running the trial. Instead, reporters and Wall Street investors were the first to know, when Lilly put out a press release.

This is unavoidable, Lilly spokesperson Nicole Hebert told BuzzFeed News by email, adding that the company did post an online video to thank research volunteers.

“Manufacturers like Lilly are not allowed to have direct communication with clinical trial participants,” Hebert said, adding that communication must go through the lead researchers at each trial site, and be run through a local ethics board. “As you can imagine, this can take time and is not a practical way of delivering a timely message,” she said. Companies must also avoid early leaks of information about clinical trial results to avoid the risk of insider trading.

But getting the news secondhand adds to the blow. William and Barbara are members of separate support groups, for patients and caregivers respectively. Barbara’s includes two men whose wives were enrolled in the failed sola trial. One was watching CNBC, and noticed a sudden drop in Lilly’s stock price flash across the screen. He went online to find out what had happened, and learned that the drug his wife was taking had failed its big test.

One of the two men couldn’t bring himself to tell his wife what had happened — and just said that doctors had decided to discontinue the drug. The other man’s wife cried when she learned the news. “He said his wife enjoyed going to get the infusions. She thought it was helping her,” Barbara told BuzzFeed News.

“It’s a tough thing,” William said.

When an experimental drug fails, clinical trials staffers at UCSF face the difficult task of discussing volunteers’ options. Some want to sign up for another trial. But that isn’t always possible — their condition may have progressed to a point where they no longer meet the eligibility criteria for the trials that are recruiting.

Most painful, for Boxer, is that some patients decide to purchase unproven “brain supplements” advertised online. “At some point one becomes desperate enough that one becomes susceptible to these charlatans peddling snake oil,” he said. But he understands the perspective of patients: “The best of scientific medicine hasn’t got me very far."

Despite the disappointments of past trial failures, and the knowledge that experimental drugs may come with unknown risks, as well as uncertain benefits, William said he was determined to keep following the scientific path.

“I have no change at all in my feeling about the importance of clinical trials,” he said. “It’s just not in my nature to give in.”