On the night of Sunday, Aug. 20, 1989, Lyle and Erik Menendez shotgunned their parents to death as they sat watching television in their Beverly Hills mansion. “They shot and killed my parents!” Lyle screams hysterically in the now-infamous 911 call, blaming intruders. After the police arrived, they didn’t even check the sobbing brothers for gunpowder residue; they initially characterized the gory murders as a “gangland-style killing” and looked into the business dealings of the boys’ father, José, to find any motives. There was a sense that only underground mob connections or a vengeful laid off employee might explain the rage necessary for the almost cinematic level of violence at the murder scene.

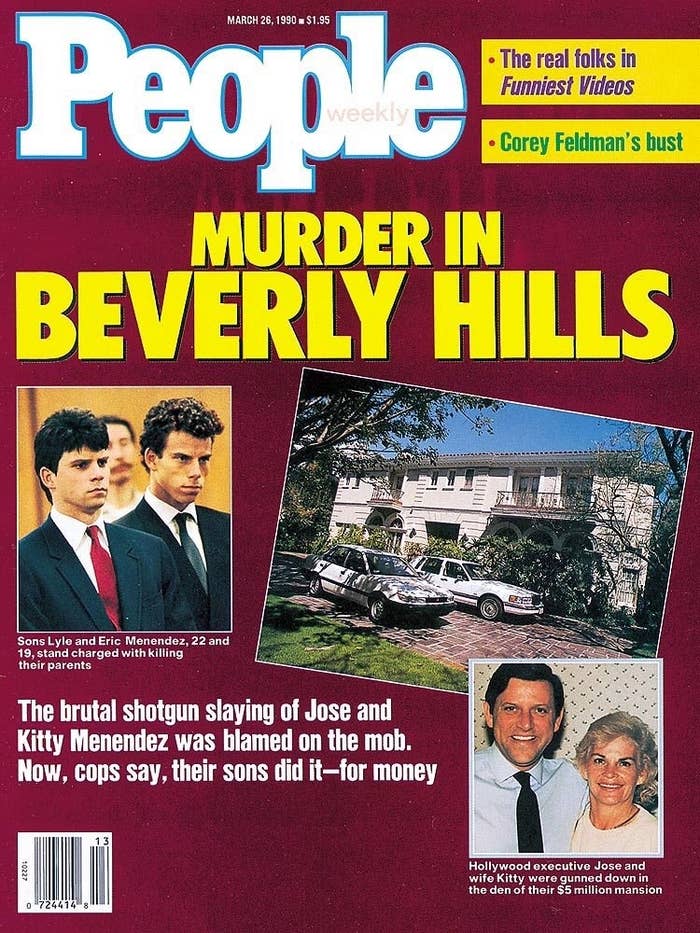

Erik Menendez ultimately confessed to a psychiatrist, and the revelation of the sons’ involvement turned the story into a national spectacle. “Murder in Beverly Hills,” screamed a 1990 burgundy cover of People magazine, revealing the narrative shift: “The brutal shotgun slaying of Jose and Kitty Menendez was blamed on the mob. Now, cops say, their sons did it — for money.”

It wasn’t until the case went to trial in 1993 that the brothers’ defense team finally revealed their own version of the story: that their father had been sexually abusing them from childhood. Throughout their two trials from 1993 to 1996, the Menendez brothers testified to that abuse, in rather gruesome detail. But prosecutors dismissed their claims as as an “abuse excuse” concocted to avoid criminal responsibility. The first trial ended in a hung jury and mistrial; the second one — which excluded any corroborating evidence of abuse, aside from the brothers’ own memories — resulted in their conviction.

Importantly, the trials took place decades before the media’s exposure of the Catholic Church sexual abuse scandal or the Jerry Sandusky Penn State story. Those cases were ultimately framed as instances of institutional failure and cover-up; they did not devolve into public spectacles questioning the individual believability of the victims. And more recently, the stories that have come out surrounding sexual misconduct, harassment or violence by Harvey Weinstein and Kevin Spacey have similarly led to investigations into methods of concealment, because of the sheer number of accusers.

But, perhaps because a family is not usually framed as a self-protective institution like a church or a university, and because there were no known victims of abuse besides the two brothers in the Menendez case, it did devolve into such a spectacle. And so for the last two decades, the Menendez brothers have largely been portrayed as spoiled sons and “inheritance killers,” as one documentary put it, just as the police and prosecution suggested.

But just as other tabloid sensations like JonBenét Ramsey and O.J. Simpson have been reconsidered during our current ‘90s-era true crime revival, the Menendez murders are being revisited as well. The new series Law & Order True Crime: The Menendez Murders, a new limited series currently airing on NBC, aligns with the best aspects of the current wave of reinterpretations of ‘90s scandals, from The People vs. O.J. Simpson to Casting JonBenet. By reconsidering sensational cases as cultural spectacles, subject to social attitudes and projections, these new treatments remind us that there is no such thing as journalistic or legal objectivity. Instead, there are stories shaped by the public’s own fears and investments in complicated topics. American Crime Story: The People v. O.J. Simpson helped examine the way racial politics suffuse the justice system; similarly, The Menendez Murders works, not because it’s great television, but because it presents the case as a legal, cultural, and media phenomenon that puts sexual abuse on trial.

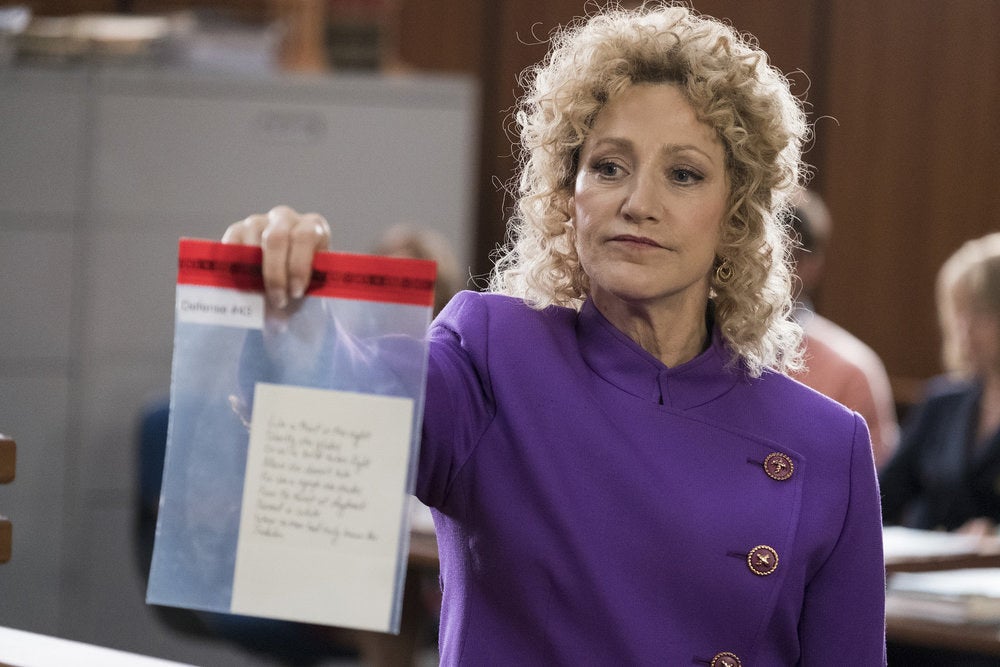

From the beginning, the series sets up the case as a set of competing narratives, all crafted by people in institutions with their own investments. The police have their own ideas about class and “normal” behavior; the media simply want to get the sensational story; and the prosecution is subject to the district attorney and their electoral politics. The story is told largely through a perspective that was never seriously considered: the brothers’ defense, led by their flamboyant lawyer Leslie Abramson (Edie Falco). And by abandoning the pretense of objectivity, Law & Order tells the least caricatured story about the Menendez murders so far. It doesn’t try to uncover some ultimate “truth” about the brothers or the family’s private melodrama, but instead highlights the role that power and institutions play in shaping narratives and establishing what people accept as fact.

The framing of the Menendez brothers as spoiled killers was first cemented in the media after their arrest in March 1990, when the police and prosecutors presented a sensational theory to the press. The Menendez brothers, they explained, had killed their parents to inherit a $14 million estate. Their evidence included psychological speculation that the brothers didn’t seem to grieve “properly” after the murders, that they engaged in what was described as a $500,000 “spending spree,” and that they ordered a computer specialist to erase a will from a family computer. In high school, Erik had written a clichéd screenplay with a friend about a teenager who kills his parents. Why Erik might have been indulging in such fantasies was never questioned; instead, the screenplay was evidence that the brothers were greedy and manipulative masterminds.

Reporters helped cement the cops’ and prosecutors’ murder-for-money theory by painting the brothers as spoiled sons who, as crime writer Dominick Dunne put it in Vanity Fair, “turned the Menendezes’ American dream into a fatal nightmare.” “Hard work, ambition, looking after your own — ‘It's what they tell you to do, and (Jose) did it,” a family friend told the Los Angeles Times. “Then this happens.’" The American family is rarely seen as a morally neutral social institution; it tends to gets the benefit of doubt as a socially positive force. So Erik and Lyle, as parent-murderers, were cultural defendants even before they were legal ones.

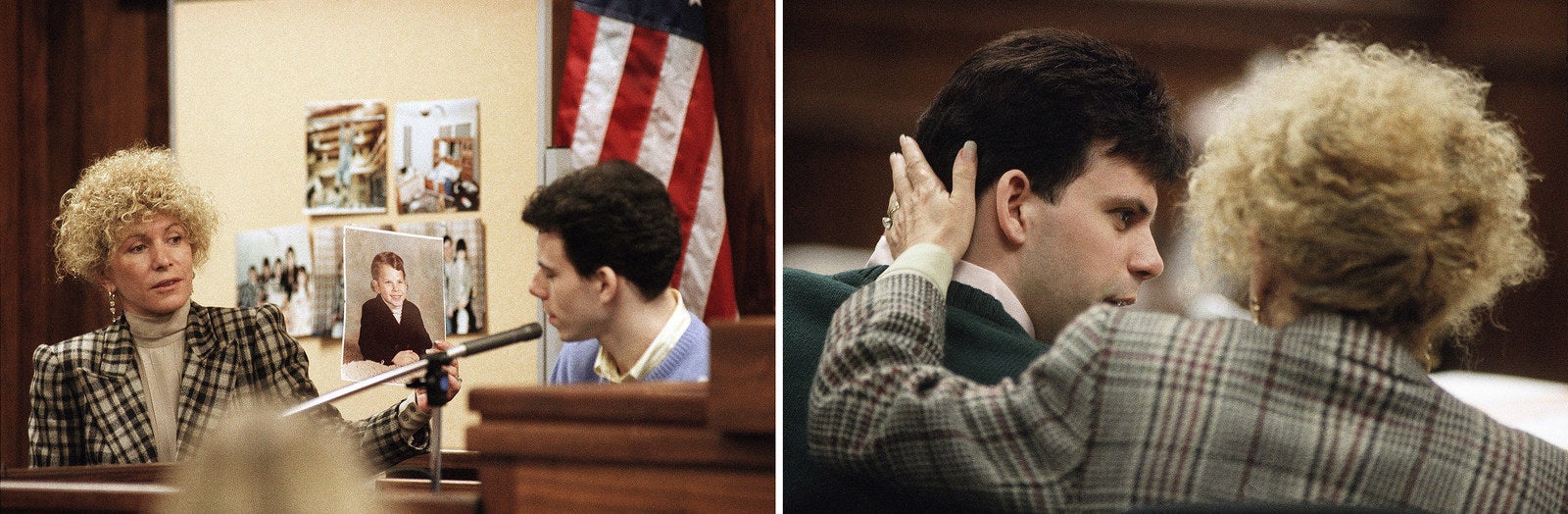

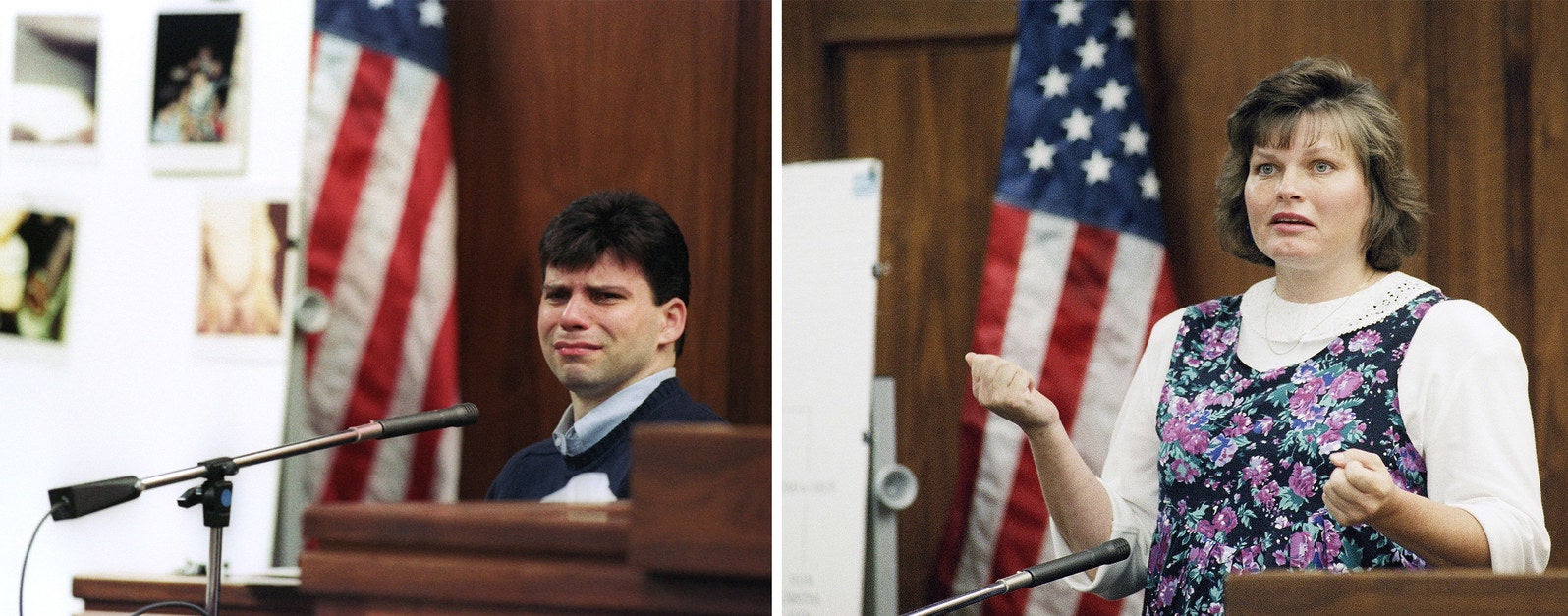

The first trial was aired live on Court TV, and the police and prosecution’s claims about the brothers as manipulative criminal masterminds were fiercely contested by an equally compelling narrative directed by Erik’s lawyer, Leslie Abramson. She put the “American dream” family on trial, skilfully shattering any idea of a model home life, by depicting José Menendez as a domineering, ruthless father, and Kitty Menendez as a kind of passive, pill-popping alcoholic. And in order to counteract the prosecutors’ depiction of her clients, Abramson tried to create an image of infantile innocence, outfitting the brothers in preppy sweaters, picking lint off them, and referring to them as “boys.”

Part of the difficulty for the defense was that in order to gain acquittal or even a manslaughter verdict, they had to demonstrate that the brothers felt they were under “imminent danger” from their parents. The defense had to take the complicated entanglements of love and fear, of paranoia and projection involved in living with sexual abuse, and streamline all of that into a straightforward narrative of a sudden explosion of violence based on one moment of fear. So the brothers testified that what caused the shooting of Aug. 20, 1989, was their fear that their parents would kill them after a family confrontation. Erik had told Lyle that their father was still molesting him, and Lyle had confronted José, who threatened to kill him if he was exposed. Years of abuse had made them so paranoid, the defense argued, that they reacted to that threat with deadly violence, borne out of primal fear.

But Abramson’s legal strategy was greeted with skepticism by the media and the public. Legal expert Alan Dershowitz saw it as part of a growing “abuse excuse” syndrome; Vanity Fair’s Dunne compared it to Lorena Bobbitt’s defense against her husband. And the brothers’ psychologically complex testimony was judged by the public based on their superficial perceptions of the family and the brothers’ appearance.

Around the time of the trial, Saturday Night Live mocked the brothers’ abuse allegations as a carefully stage-managed ruse, in a sketch where John Malkovich and Rob Schneider acted out a parody of their testimony as wild theatrics meant to game the system. “Lyle has all the instincts of a great neurotic actor, on the order of Marilyn Monroe, Montgomery Clift, or Judy Garland,” wrote Dunne in another Vanity Fair article, as if he were reviewing a Broadway play. Of Erik, he noted, “He did break down, but only once, and it had none of the pathos or drama of Lyle’s first cry.” Observers convinced that they could see through the brothers “performance” were not swayed by the fact that two cousins — from both the fathers’ and mothers’ sides of the family — confirmed during the trial that Erik and Lyle had confided in them about the sexual abuse as a child and a teenager, respectively.

That first trial ended with hung juries for both brothers in January 1994. But that verdict did not cause a widespread cultural reckoning with the brothers’ claims. Instead, the first two “quickie” network television movies about the case that aired that year give a sense of how the prosecution’s narrative dominated the media representations. Both the Fox network version, Honor Thy Father and Mother: The Menendez Murders and the three-hour CBS version, Menendez: A Killing in Beverly Hills, bought into the contentions about the financial motive for the murders. They reenacted the spending spree, the will erasure, the parent-murdering screenplay. Both include a moment, from a tape recorded by the prosecution’s psychiatrist, in which Lyle coldly compares missing his mom to missing his dog.

The movies accepted the defense’s melodramatic depiction of the domineering father and pill-popping mother, but neither grapples with the accusation of sexual abuse, except to mention it as one of the most compromised and sensational claims from the trial. The three-hour CBS version more explicitly frames the abuse as an excuse concocted for the trial. A female juror who seems convinced by the brothers’ defense — saying “I know an abused child when I see one” — is written as a hysterical believer, not a rational thinker making an informed decision. In other words, much like the SNL parody, the movie acts as judge and jury and implies that the brothers’ theater conned an objective system.

Ultimately, the prosecution’s Hitchcockian caricature about rich, evil masterminds killing for money was never subjected to the same skepticism as the “abuse excuse.” By the time of the second trial in 1995, the judge blocked cameras in the courtroom and only allowed the brothers’ own testimony about the abuse. Without the corroborating testimony of the cousins, they were convicted of their parents’ murder in March 1996, and received a sentence of life without the possibility of parole. And the Menendez brothers have been frozen in that image of guilt — until now.

In January, the brothers were also the subject of a two-hour ABC documentary, Truth and Lies: The Menendez Brothers — American Sons, American Murderers. And in June, Lifetime aired a movie starring Courtney Love as Kitty Menendez. All three 2017 televised reconsiderations of the Menendez brothers promised “new” angles in order to stand out. But in many ways, the first two programs to air this year ceded ground to the established tropes of the case, failing to examine how they were shaped in part by the cultural skepticism around sexual abuse.

The ABC documentary was the first look back, and teased new insights from those who covered the case at the time, like Court TV reporter Terry Moran. Towards the end, Moran makes a crucial point about the trial: “We don't wanna think ‘oh, boys get raped by their fathers,’” he says. But the documentary doesn't fully grapple with what that cultural dilemma really meant for the way the brothers’ claims were interpreted by the public or the legal system.

Instead, Moran — much like commentators in the ‘90s — frames sexual abuse as a question of individual believability, recalling: "I saw this vein start popping out of his forehead … that emotion. That's what a victim looks like." He reminds viewers that the second trial excluded the testimony of relatives corroborating the brother’s sexual abuse claims, but the politics behind that decision are not explored, beyond mentioning the impact of the O.J. acquittal. Instead, Pam Bozanich, the prosecutor from the first mistrial, is brought in to dismiss the “abuse excuse” again.

The Lifetime movie Menendez: Blood Brothers, was, once again, a rehash of the same family stories, this time with a sympathetic slant on the brothers and their mother. But the film never really provides any new information, and stays within the realm of the family melodrama. Ultimately, it only demonstrates that changing the slant of the story without exposing the narrative scaffolding, and how it emerged through legal strategies, is not enough of a reconsideration.

Law & Order finally exposes that scaffolding, even while being openly biased toward the defense’s perspective. In an interview with Variety, producer Dick Wolf said, “We’ve had sort of a collective agenda […] I think people are going to realize, ‘Well, yeah they did it, but it wasn’t first degree murder with no possibility of parole.’ They probably should have been out eight or ten years ago.” And from the beginning, this retelling has made Falco, playing Leslie Abramson, its star figure. Just as Marcia Clark was the redeeming moral center fighting for gender justice in The People v. O.J. Simpson, Abramson is the warrior of this sad tale, fighting for abused “boys,” as she calls the young men she represents.

While her dialogue sometimes comes off as didactic, Falco’s version of Abramson reframes the sensational media stories about the case, always giving the brothers the benefit of the doubt. “People like that don’t just wake up and turn into Charlie Manson,” she observes in the second episode. When an investigator expresses her skepticism about the case by moralizing about shooting a mother in the face, Abramson retorts: “I can't imagine the kind of pain that must exist between a mother and child to provoke that kind of violence.” In a strategy session in the third episode, Abramson contests the media’s sensationalizing fascination with the famous “spending spree,” which seems less shocking when considered in terms of the brothers’ lavish spending even before the murders.

She also reminds us that even seemingly neutral legal institutions are forced to play into public prejudices for political and electoral reasons. In one scene, Abramson proposes a plea deal and the prosecutor Bozanich (Elizabeth Reaser) shoots her down, saying, "Kids killing their parents is a crime against society." But Abramson quickly redirects her anger to the district attorney, whom she knows is behind the decision: "Ira, you are using these boy as a pawn to get reelected. It's desperate and it's unfair." Subsequent episodes will also show that there was collusion between the judge and the D.A. to ensure a guilty verdict in the second trial, in the aftermath of the Rodney King and O.J. Simpson acquittals.

Even the fictionalized portrayals of the brothers’ aunts and uncles — some of whom appear in the ABC documentary — are shown to have different interests in the family estate, and thus different investments in believing the brothers’ claims. And psychiatric experts are not immune to self-interest, either. In the real-life media narrative around the trial, the prosecution psychiatrist's testimony dominated the public's perception of the brothers' honesty and motives. Here, the series instead shows him as ethically compromised, with his own motivations, and portrays Erik's confession of their sexual abuse from the defense psychiatrist's point of view.

The show’s attempt to make drama out of agendas and institutions — rather than the family story of the brothers themselves — has often made for clunky or less than riveting television. Reviewers have focused on the clichéd dialogue expected from a Dick Wolf production, because it “restricts any potential for a more detailed psychological profile” of the Menendezes. Yet the strength of the show is not in providing psychological profiles of the brothers or making them vivid characters, but in questioning how they came to be imagined or represented as “evil seeds,” as Lyle describes the prosecution’s depiction of them in the fifth episode.

We might never get to know the “real” Erik or Lyle Menendez on this program, but we do get a sense of how they became public caricatures. This old-fashioned show is making network television by reframing sexual abuse as a question of institutional power, whether that institution is the law, the media, or the family. It moves away from the usual framing of sexual abuse as an individual question of a victim’s believability, by accounting instead for why and how the courts and the public come to decide what constitutes truth.

Last year, the brothers made news because they filed an appeal after a new law might allow retrials for those convicted after courts excluded corroborating sexual abuse evidence. This show finally promises to reckon with that legal change. It radically suggests that the cultural and legal skepticism and biases around abuse — and not the sensational shotgun blasts in Beverly Hills — might be the most shocking aspect of the Menendez brothers story after all. Law & Order can’t solve all of the mysteries that haunt this case, and its interpretations of events is by no means irrefutable, but it is finally asking all the right questions. ●