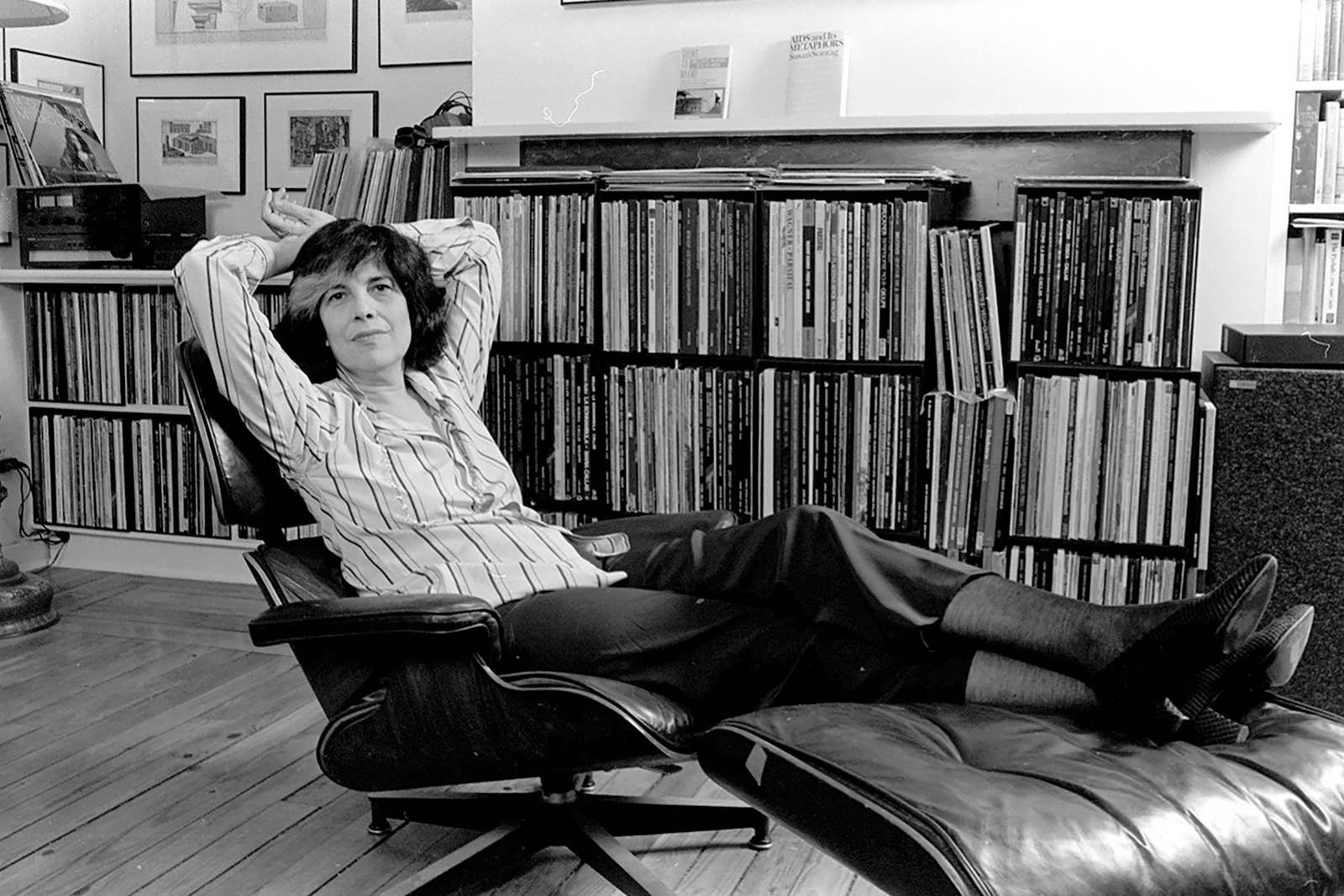

Susan Sontag’s fame was always paradoxical. It made no sense that a writer publishing in the so-called little magazines, like Partisan Review and the New York Review of Books, on topics like structuralist philosophy or the history of interpretation, could cross over to become a major literary star. But, improbably, she did.

Sontag became an icon of ’60s radical chic, launched by the essay “Notes on Camp,” most recently invoked as the organizing text for the Met Gala’s 2019 theme. Throughout her career, she was also a filmmaker, playwright, short story writer, documentarian, and an experimental turned bestselling novelist. She made provocative assertions — that the white race is “the cancer” of human history, or that the 9/11 hijackers were not cowards — that kept her active in the public imagination. Through her sober, book-length studies On Photography and Illness as Metaphor, she helped change the terms of public debate around phenomena that permeated culture.

But even for people who might not have engaged with her work, Sontag became an almost cartoonish symbol of intellectualism and high literary seriousness. She played herself as a talking head in Woody Allen’s 1983 movie Zelig, was caricatured on Saturday Night Live, and was even name-dropped in Gremlins 2 (1990) by one of the creepy creatures as a marker of civilization, on par with the Geneva Convention and chamber music.

But despite her celebrity, Sontag was notoriously guarded about her personal life. Her work was not, for the most part, the kind of direct, first-person essays or journalism that would let you into her world, in the mode of contemporaries like Norman Mailer or Joan Didion (an approach that is now de rigueur in the internet age). Her writing was famous for its academic tone (modeled after French and German cultural critics) and for her obsession with (mostly male) European writers and thinkers.

Because Sontag’s essayistic and fictional voice was so impersonal, the glimpses into the woman behind the writing that we’ve been granted since her death in 2004 — in her diaries and others’ memoirs — have felt like a revelation. In recent years a steady stream of writers have reconsidered her life and legacy: Terry Castle’s 2005 London Review of Books essay “Desperately Seeking Susan”; the 2008 memoir Swimming in a Sea of Death, a narrative of Sontag’s torturous final years by her son, David Rieff; the novelist Sigrid Nunez’s memoir Sempre Susan; and the 2014 HBO documentary Regarding Susan Sontag.

These accounts started to lay bare Sontag’s outrageous diva tendencies, her cruel treatment of her women lovers, her inability to reconcile herself with death, her insecurities and anxieties, her loves and losses. The romantic part of her life, and how it was reflected in her work, is less familiar to most readers who are casually familiar with Sontag or her writing.

Sontag came of age — and found her voice as a writer and public figure — at a moment before it was possible to be a major literary star as a queer woman.

Throughout her life, most profiles of Sontag — and there were many — mentioned only her early marriage to the sociologist Philip Rieff. They wed in 1950 when Sontag was 17, a precocious undergrad at the University of Chicago. That partnership became part of the Sontag mystique and the lore of her origins as a young genius. But the public focus on her only marriage also implied that she was straight. It was only in 2000, in reaction to the publication of an unauthorized biography that was about to out her, that Sontag finally talked about having dated women as well as men in a New Yorker profile. (Even then, she denied that the celebrity photographer Annie Leibovitz, her on-and-off girlfriend in the last decades of her life, was anything more than a friend.)

Now, 15 years after Sontag’s death, comes the authorized estate biography: the comprehensive and weighty tome Sontag: Her Life and Work, by the writer and translator Benjamin Moser, who was handpicked by Sontag’s son and agent to tell the story of her life. Already the book has made headlines for its revelations about Sontag’s almost abusive treatment of Leibovitz, and her supposed authorship of her husband’s most famous book on Freud.

The book’s reception has been mixed. The writer Leslie Jamison praised Moser’s refusal of strict chronology in favor of exploring recurring themes. But Merve Emre for the Atlantic points out that in his attempt to organize Sontag’s life into those themes, Moser sometimes reproduces clichéd binaries, like beauty versus intelligence or mind versus body, that Sontag’s own work contradicted (though one might also argue those gendered contradictions helped make her celebrity). In the New Yorker, Janet Malcolm, who is famously against the biographical genre’s pose of objectivity, raises questions about Moser’s perspective. She writes that “Moser can barely contain his rage at Sontag for not coming out during the AIDS crisis,” and he “cannot forgive her for her refusal to do so.”

Malcolm’s accusation — that Moser is punishing Sontag through the book because she never came out — raises the broader question of biographical objectivity, and of what it would actually mean to consider Sontag’s life, work, and legacy from a queer perspective.

In fact, Moser didn’t expect writing about Sontag’s sexuality to be an especially complicated or central aspect of the project. “I couldn’t imagine that anyone she knew, or any of her readers or admirers, would care either way,” he told an interviewer earlier this month. “But as I began looking into her life and her relationships, I learned that she had never acknowledged her sexuality publicly, and indeed she lied about it constantly.”

Sontag came of age — and found her voice as a writer and public figure — at a moment before it was possible to be a major literary star as a queer woman. And that impossibility shaped many of Sontag’s refusals as a writer: her vexed relationship to the personal, her pleasure in abstraction. Those impossibilities are actually a big part of what created the Susan Sontag myth with which Moser — and the rest of the world — became enthralled.

In some ways, the genre of biography, which traditionally focused on the great lives of great men, is incompatible with the project of grappling with the meaning of marginalized subjects. This is why some biographies drop the veneer of objectivity and unabashedly tell a life from a queer perspective, or a feminist perspective. But this was not — despite Malcolm’s claim — Moser’s intention; even the sober title, Her Life and Work, invokes the kind of universal, serious literary biography that perhaps Sontag herself would’ve wanted.

Moser, like earlier Sontag biographers — including Carl Rollyson and Lisa Paddock, who wrote the sensationalist The Making of an Icon, and German critic Daniel Schreiber — ultimately tends to limit his exploration of Sontag’s queer identity to her personal life and her private writing, rather than imagining how it might have defined the entirety of her work. In his introduction, Moser notes, “Despite occasional male lovers, Sontag’s eroticism centered almost exclusively on women, and her lifelong frustration with her inability to think her way out of that unwanted reality led to an inability to be honest about it — either in public, long after homosexuality ceased to be a matter of scandal, or in private, with many of those closest to her.” He adds: “It is not a coincidence that the preeminent theme in her writing about love and sex — as well as in her own personal relationships — was sadomasochism.”

But the impact of Sontag’s sexuality is worth tracing beyond her private life. Sontag: Her Life and Work is strongest, and most freshly compelling, when — sometimes directly, sometimes inadvertently — it tells a story that suggests Sontag’s development as a writer was inextricable from her queerness. Sontag's position in the American writing pantheon is unique, and that uniqueness is the product of a complicated mix of queer self-denial and self-making that we are only just beginning to see take shape.

Sontag was born Susan Rosenblatt in New York in 1933 to an upper-middle-class fur trader father, who died when she was 5, and a mother who became addicted to alcohol. (Her mother eventually remarried and Sontag mostly ignored her stepfather, but she kept his last name. “I wanted a new name,” she later wrote in a diary, “the name I had was ugly and foreign.”) In his biography, Moser — like Sontag herself — emphasizes her complicated relationship with her withholding mother as a kind of blueprint for her tortured relationships with women throughout her life, from her earliest up to her last, with Leibovitz.

The impact of Sontag’s sexuality is worth tracing beyond her private life.

“So now I feel that I have lesbian tendencies (how reluctantly I write this),” Sontag confessed to her journal in 1948, at 15, as she was heading to college at Berkeley. And it was there, through the proximity to San Francisco, that Sontag started coming into her own queerness. She discovered Djuna Barnes’ Nightwood and explored gay bars, and her diaries are full of lists of homosexual lingo. Her first meaningful romance with a woman (the writer and model Harriet Sohmers) rendered her “reborn,” as she wrote in 1949, and as the first volume of her journals, published by her son in 2009, was titled. She notes “the incipient guilt I have always felt about my lesbianism — making me ugly to myself — I know the truth now — I know how good and right it is to love.”

Later that year she transferred to the University of Chicago: her dream school, because there were no sports teams and everyone wanted to debate Plato. She was presented with a set of values — a belief in the superiority of the great books and high culture and a revulsion toward philistinism and commercial culture — that she internalized and would carry with her for the rest of her life. This was also when she met Philip Rieff, her 28-year old professor; within a week of meeting her, he had proposed. By the next year they were married and a year later, in 1952, Sontag gave birth to David, her only child.

Sontag became a grad student in English, first at the University of Connecticut and later at Harvard. But much of her early intellectual work was in service of her husband’s career. Moser’s biography has made headlines for the argument that Sontag wasn’t just a coauthor of Rieff’s most famous book, Freud: The Mind of the Moralist, but in fact a kind of ghostwriter.

Sontag herself claimed she wrote “every single word” of the book. Moser identifies echoes of Sontag’s own lifelong battle against psychological interpretation — and the aggression inherent in all forms of interpretation — in The Mind of the Moralist’s arguments. He notes her calling out Freud’s misogyny, and as part of his evidence for her authorship points out that Rieff’s later writing on Freud lacked Sontag’s feminist take on his work.

Moser also astutely points to the fact that the book’s very particular reading of Freud’s theories of sexuality seems unlikely to have come from anti-gay Rieff either. “Freud assaulted prevailing prejudices by showing ‘normality’ in its accepted meaning to be another name for the conventional,” he quotes from the book. (I’m convinced by Moser’s argument, but arguably, this is also one of the sections where his biographical objectivity hits a wall; an explicitly queer or feminist account could make more interesting arguments about the richness and limitations of Sontag’s thought by contextualizing it with other queer or feminist critics of the moment.)

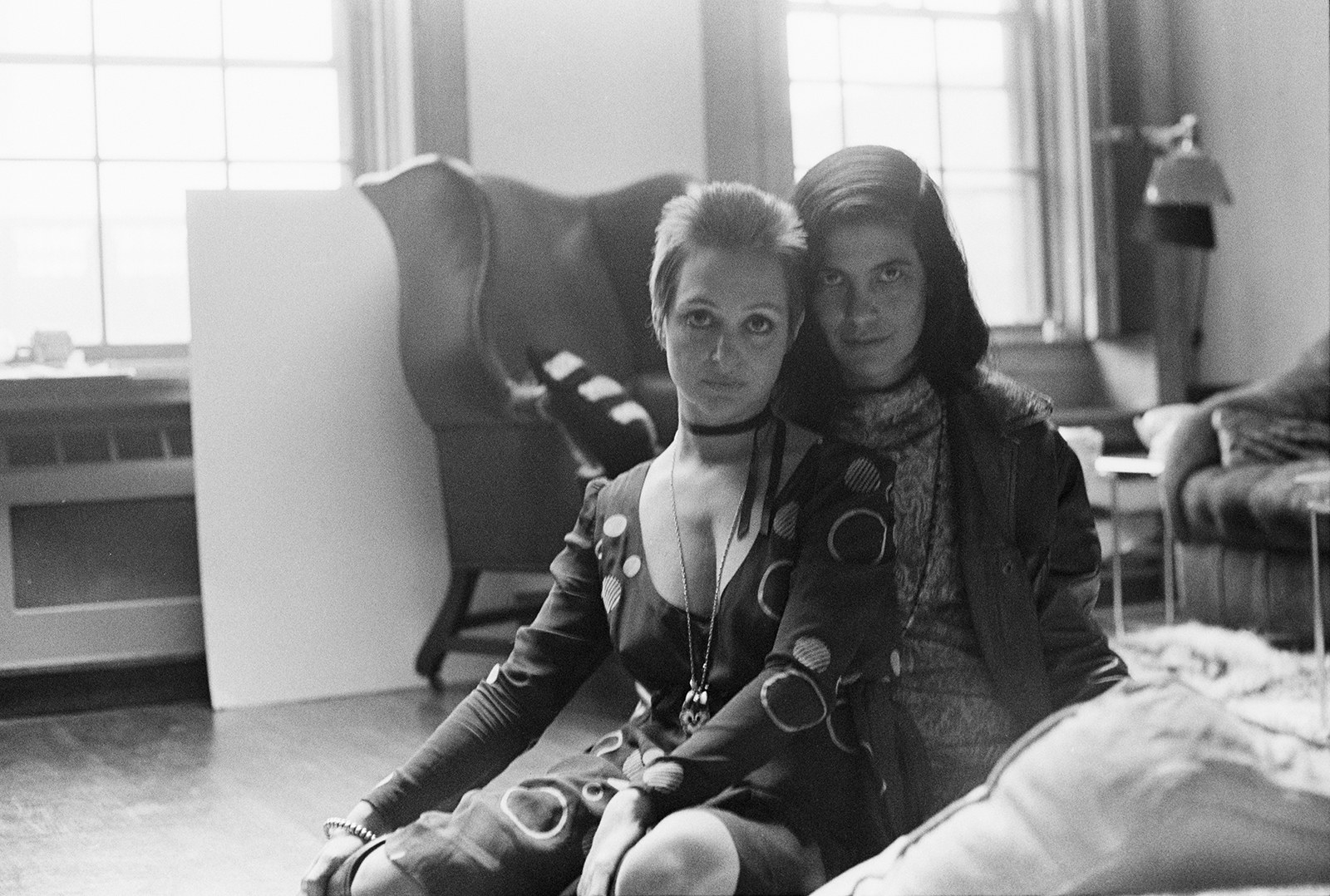

Moser reveals that Sontag gave up her rights to the book’s coauthorship as part of her acrimonious 1957 separation and divorce from Rieff. During a fellowship at Oxford and some time in Paris, she had decided to leave her husband. She moved to New York and fell in love with the Cuban playwright María Irene Fornés (Sohmers’ ex-lover). Sontag was supporting herself as an editor at Commentary and professor of religion at Columbia and refused alimony, but the divorce made the New York tabloids because of her husband, who refused to give her custody of their son. At the time, homosexuality was still a scandal, and Rieff tried to argue that Sontag’s relationship with Fornés made her an unfit mother.

Surprisingly, Moser claims that those particular accusations never made the paper, but in Schreiber’s 2014 biography, he recounts that the New York Daily News ran an article covering the in-court divorce proceedings under the headline “Lesbian Religion Professor Gets Custody.” A friend of Sontag’s, the poet Richard Howard, told Schreiber that the exposure terrified Sontag, who never came out to her family, and was a big part of why she feared coming out (and arguably never did).

“The only writer I could be is the kind who exposes himself,” Sontag wrote in a 1959 journal entry. When she found her voice as a public intellectual in the 1960s, in the Partisan Review and New York Review of Books, it was in part through writing about gay-coded topics, like camp (which, in the essay, she declares herself “offended” by), or Jack Smith’s films. But what she didn’t write then — explicitly autobiographical essays, or fiction — is also telling; like her polemical opposition to interpretation, Sontag’s early avoidance of those forms makes more sense when you look at it through the lens of her queerness.

Sontag’s own journals, which Moser quotes, link her writing and her identity in complicated ways. “My desire to write is connected with my homosexuality,” she wrote in 1961. “I need the identity as a weapon, to match the weapon that society has against me. It doesn’t justify my homosexuality. But it would give me — I feel — a license … Being queer makes me feel more vulnerable. It increases my wish to hide, to be invisible — which I’ve always felt anyway.”

Moser’s biographical readings illustrate how revealing some of Sontag’s supposedly impersonal work really is. He highlights the “emotional color that hid behind Sontag’s best polemics,” like her book-length essay On Photography, often interpreted as an argument against the art form. He writes, “Her ambivalence meant that these writings were addressed in the first instance to herself, toward purging a part of herself she distrusted...She was Arbus and freak, photographer and subject, judge and accused, executioner and victim.”

Moser quotes her as saying, “I can’t hope to have the kind of influence that Norman Mailer and Paul Goodman have because I can’t imagine writing personally the way they do.” This speaks not just to her vexed relationship to the personal in her writing, but her cross-gender identification with male authors. And as her career progressed, she became somewhat more self-revealing by way of writing about these men who had influenced her.

In one of her later essay collections, Under the Sign of Saturn (1980), Sontag writes about some of her most treasured writers: Goodman, Elias Canetti, Walter Benjamin, and Roland Barthes. Moser, like Phillip Lopate in his study Notes on Sontag, convincingly unpacks how Sontag’s admiring retrospectives of these men’s lives and works could basically be read as autobiographical portraits of herself. The essay about Goodman, in which she addresses his gayness, was one of the most personal she ever wrote.

This shift of opening up over time also happened in Sontag’s fiction. Her first experimental novels — The Benefactor (1963) and Death Kit (1968) — and her films were guided by the anti-psychological, plotless style of midcentury French nouveau roman (“new novel”). In the ’80s, Sontag wrote in her journal about how her “inability to write narrative fiction comes from an inability (perhaps, more accurately, a reluctance) to love,” once again connecting her writing and queerness in ways that Moser doesn’t unpack.

But toward the ’90s, Sontag renounced that experimental style, explaining that she liked the “ideas they had about fiction much better than the fiction that they themselves were writing.” Eventually, she did write a traditional narrative with her next-to-last historical novel, the 1992 bestseller Volcano Lover: A Romance, which most critics deem her most successful fictional work. Set in Naples, it focused on real-life characters: Sir William Hamilton, a British ambassador at Naples; his wife, Emma, a famous beauty; and her scandalous affair with Lord Nelson, a military hero of the age. As Moser outlines, the characters spoke to different aspects of Sontag’s own personality. “The collector par excellence, the aging Cavaliere, is a melancholic for whom beauty and art are medicine,” Moser writes, noting how the character spoke to Sontag’s own struggle with depression. The novel, he argues, “united the rigor of her best essays to the ambivalence of her best stories.”

It’s striking that a writer who symbolized intellectual authority was at a loss for words when it came to her own story.

Yet even as Sontag found ways to be more herself — or stage aspects of herself — in her work, she seemed unable to do that in her life. Moser writes that even toward the end of her life, Sontag never reconciled herself to her sexuality. “I don’t think same-sex relationships are valid,” she told her assistant, who had to ask her to stop pretending that Leibovitz was just her friend. ”She came up with all of these things that you hear from these awful people who call themselves Christian,” the assistant recalled, specifically remembering that Sontag told her: “The parts don’t fit.”

Sontag’s “coming out” in the New Yorker in 2000, after the publication of her last novel, In America, was telling in that respect. It was the writer Joan Acocella who told Sontag to come out on her own terms before she was outed by biographers. “Well she was terrified,” Acocella tells Moser. “She was absolutely terrified, and she said to me, ‘I don’t know the words to use. I don’t know what words to use.’” (Terry Castle, whose unapologetically lesbian essay about Sontag memorably describes her as “quite fabulously butch,” also wrote about how terrified she was of those biographers).

It’s striking that a writer who symbolized intellectual authority was at a loss for words when it came to her own story. Acocella had to help her figure out what to say. Eventually, she said this: “That I have had girlfriends as well as boyfriends is what? Is something I guess I never thought I was supposed to have to say, since it seems to me the most natural thing in the world.” In spelling this out, she used such a strangulated tone that it made Acocella, sitting next to her, cry. (Later, the openly gay transcriber tasked with writing up the interview also cried.)

The difference between the casualness implied in Sontag’s words as they were eventually printed and the private agony she felt over revealing them tells us more about Sontag’s relationship to her sexuality, and her inability to be vulnerable in public, than anything she ever wrote.

Sontag came to believe that her fiction was a much fuller representation of herself than the essays that made her famous, and, in one of her diva-isms, became furious when she was asked about the essays later in life. Moser cites Castle’s insight that Sontag didn’t like talking about “Notes on Camp” in particular because it was too obviously queer for the later universally high-minded, sexuality-transcending “Susan Sontag” persona she’d established.

That Moser has to reference Castle rather than make the observation himself reveals, in some ways, the limits of interpretation in “straight” biography. Despite Malcolm’s complaint about Moser inserting his queer agenda into the narrative, Moser doesn’t actually condemn Sontag for not coming out. He simply points out, correctly, that by the time her book AIDS and Its Metaphors was published in 1989, the kind of essay writing that Sontag preferred — speaking as a kind of universal voice about a cultural problem — was no longer really possible. AIDS activism demanded making the private public, and Sontag’s refusal to do so rendered her voice, for the first time, irrelevant.

More than once, Moser situates Sontag’s writing about camp and pop culture alongside feminist and African American attempts to expand the canon. (He doesn’t mention queer theory, which came later.) But Sontag herself was against such expansions. Which brings us to the question of her legacy.

“Though many would fashion themselves in her image, her role would never be convincingly filled again,” Moser writes toward the end of the book. “She created the mold, and then broke it.” In fact, part of what is fascinating about Susan Sontag as a writer is that despite her fame, she exerts relatively little influence on contemporary writing style. Everyone wants to be Susan Sontag, but no one writes like her.

Everyone wants to be Susan Sontag, but no one writes like her.

The voice of Twitter and the internet, which demands that everyone politicize their identity, mashing up high and low references while matching the silliness of pop culture in tone, would’ve horrified Sontag. Even her essays focused on popular culture — like “Notes on Camp” or “The Imagination of Disaster,” about science fiction films — are not even remotely lighthearted; they provide deeply researched theories about their subjects, contextualizing them in history and in culture. She wrote the camp essay in part because, as she notes, she wanted to figure out how to capture a sensibility — as opposed to an idea — in writing. She might analyze the humor of science fiction films in the essay, but she doesn’t perform it in her work.

In books like Craig Seligman’s Sontag & Kael, or Michelle Dean’s Sharp: The Women Who Made an Art of Having an Opinion, Sontag is placed in conversation alongside mostly straight, white American women writers that she never had time for, which ultimately highlights how unlike them she was. Writers like Nora Ephron or Mary McCarthy used their personal lives, humor, and vernacular in ways that Sontag would’ve found vulgar and anti-intellectual; she would have called them journalists, and meant it as an insult. Pauline Kael literally wrote an entire article against film theory, while Sontag wrote one theorizing what is meant by the cinematic (as opposed to the theatrical).

It’s telling that America’s one homegrown philosophical tradition, pragmatism, hinges on the use value of ideas. Sontag found herself in a Continental tradition that was against the ease of the practical. She never quite fully disidentified with the mostly masculinist European modernist tradition she admired. “It’s not as good as [Walter] Benjamin, is it?” she asked a friend after On Photography was published. Yet in her very particular interpretations of some of those writers’ same concerns for an American audience, she created the Susan Sontag voice and persona. It was also in working out a space for herself as a (secretly) queer woman in that mostly male-identified tradition — finding pleasure in abstraction, pursuing difficulty in often self-flagellating ways — that Susan Sontag made history.

In the final pages of his biography, Moser situates Sontag in world history. “She was there when the Cuban revolution began,” he writes, “she was there when the Berlin Wall came down; she was in Hanoi under bombardment; she was in Israel for the Yom Kippur War. She was in New York when artists tried to resist the pull and tug of money and celebrity, and she was there when many gave in.”

Those are the kind of clichéd images of historical moments necessary to sell a big, mainstream, “serious” biography about a figure “of their time.” But the more surprising portrait Moser offers is one of a queer woman terrified of the implications of that truth about herself, grappling with constraining conventions in both life and aesthetics, trying to transcend it all through her art.

It’s hard to know what Sontag would have thought about a more deliberately queer reading of her life and work; she might have seen it as a symptom of politics taking over art, or a reductive distortion of the richness of her writing. But it might also be the most Sontagian gesture of all. In an essay about Simone Weil, she once wrote, with characteristic skepticism about binaries: “An idea which is a distortion may have a greater intellectual thrust than the truth … The truth is balance, but the opposite of truth, which is unbalance, may not be a lie.” ●

Correction: H. Magnus Enzensberger's name was misspelled in a photo caption in a previous version of this post.