The figure of the gay man working behind the scenes to make others — especially women — beautiful, acting as a sounding board and sidekick, has been a dominant trope of queer narratives for decades. This unthreatening character type, which appears in everything from ’80s movies like Mannequin to Queer Eye (old and new) to Sex and the City, helped make gay men respectable by depicting them in service of something other than themselves. It is no accident that the beauty industries — the worlds of fashion and makeup — have historically been some of the few real professional spaces that allowed for openly gay men, or those coded as such, and even bestowed on them a measure of celebrity.

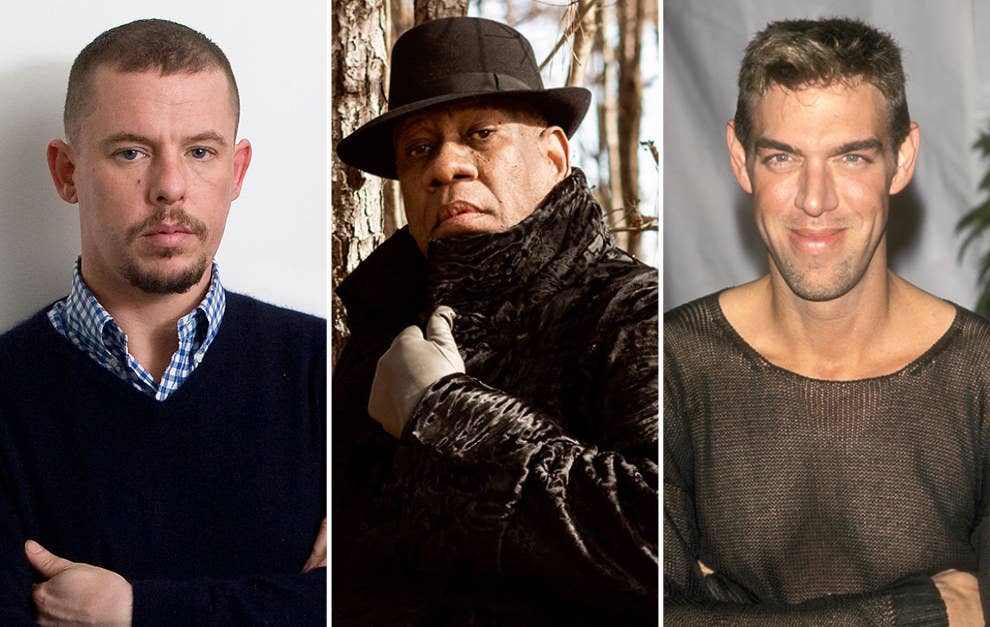

Three recently released documentaries attempt to bring real-life queer creatives out from behind the scenes of these industries, focusing on their lives and the meaning of their work. Tiffany Bartok’s Larger Than Life: The Kevyn Aucoin Story takes up Aucoin’s legacy as a trailblazing makeup artist, while celebrated fashion designer Alexander McQueen is the subject of Ian Bonhôte and Peter Ettedgui’s McQueen, and Kate Novack’s The Gospel According to André tells the story of iconic former Vogue editor André Leon Talley. (McQueen and Aucoin, who died in 2010 and 2002, respectively, were not alive to help shape their life stories, like Talley was.) Each of these men turned to the fantasies of fashion to reinvent themselves and shape culture, after coming of age before diverse gender and sexual identities — and, for Talley, discussions about race and racism — became part of the pop culture mainstream.

The three films are varyingly successful in their attempts to bring out the complexities of protagonists who all sometimes struggled to define themselves, or to resist being defined by others. The portrait of Aucoin, aided by his self-documentation and his family and friends’ openness in talking about the difficulties he experienced as a queer man, is the most intimate and nuanced, while the other two films don’t necessarily offer the same kind of insight into their protagonists’ private lives as they do into their work. In McQueen’s case, the directors have been open about their fears of offending his family by focusing on his gay identity, which Bonhôte considered “vulgar and simplistic”; Talley, as a black man of an earlier generation coping with two different strains of respectability politics, is guarded on the subject of his personal life, and clearly his friends and family follow his lead.

Considered together, the three films reveal not just the accomplishments and struggles of these men, but also some of the tensions that result from trying to tell their full stories now. They raise questions about the extent to which sexuality shaped these men’s lives, and how it should be considered when interpreting their work. Each film explores — and avoids — these issues in its own ways.

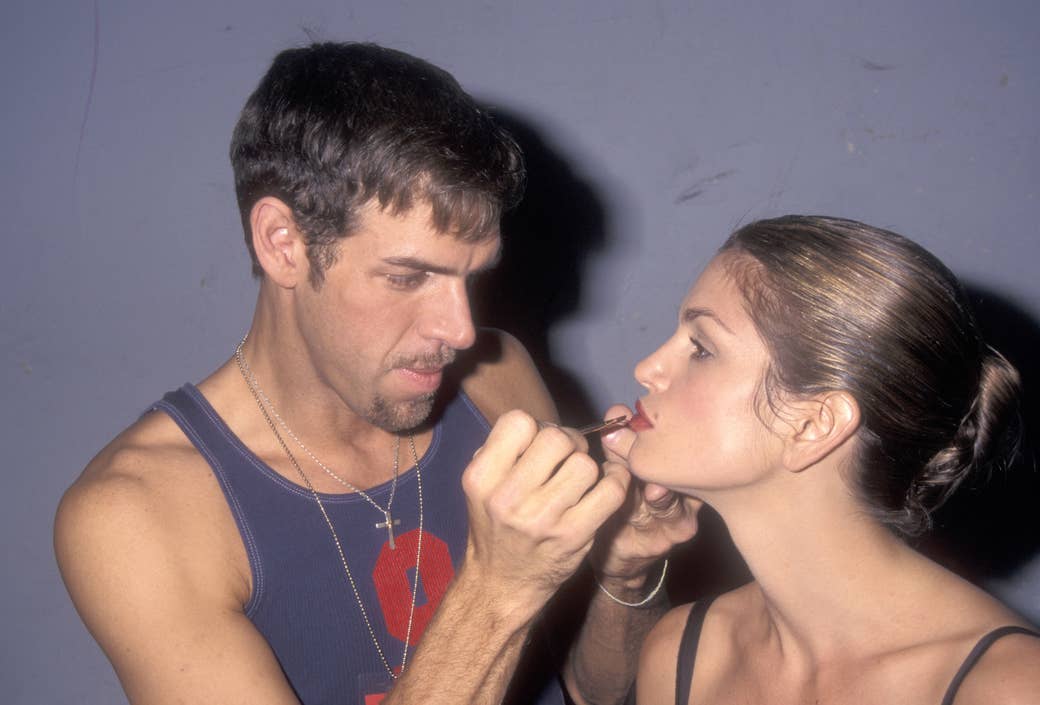

Kevyn Aucoin is less widely known than McQueen or Talley outside fashion circles — in fact, Bartok was inspired to make the film because of this erasure — but he became a star in the ’90s thanks to his pioneering contouring makeup technique. Contouring worked as a kind of Photoshop before Photoshop, and Aucoin, who mastered the form long before Kim Kardashian launched it into a full-blown beauty craze, counted Cher, Gwyneth Paltrow, Whitney Houston, and Naomi Campbell as his clients (and, in the case of Cher, who is interviewed at length for the documentary, also as a friend). At his height, he appeared on Oprah, arrived at his book launch party with Janet Jackson, and even played himself as Carrie Bradshaw’s makeup artist in that famous episode of Sex and the City where she falls on a catwalk.

“He wanted everyone who was misunderstood or on the fringes to be seen and beloved.”

Larger Than Life is the only one of the three films that really probes behind the idea of Aucoin as a success story to follow the throughline of his life, specifically as a gay man struggling with his gender identity. We see him growing up as a Streisand-loving femme kid in Louisiana in the ’70s, facing the usual slurs — faggot, sissy, pansy — because of his interest in “girl things.” His father was on a baseball team and wanted him to join, but, as he puts it, “throwing a ball instead of creating art is not what I wanted praise for.” His mother, whom he was close to, read him articles warning him that being gay would turn him into a psychopath. “I was 8 years old,” he says, sadly, in a recording. “I kind of waited for this Jekyll and Hyde thing to happen.”

The documentary is enlivened by Aucoin’s self-documentation. Like other gay men from the time who struggled with their self-image in a hostile culture, he was drawn to cameras and performance, and made videos that seem now like an attempt to create his own affirming pop culture. (In one of them, a fellow makeup artist he met working at a mall dresses up as a drag queen and interviews unsuspecting straight locals about town happenings.)

For Aucoin, makeup, fashion magazines, and photography functioned, like those videos, as possibilities for defining and transforming himself and others. His mission with makeup was “to right a wrong from his childhood,” says one of the editors he worked with. “He wanted everyone who was misunderstood or on the fringes to be seen and beloved.”

Aucoin quickly became an in-demand makeup artist when he arrived in New York, right at the transitional moment between the ’80s and ’90s when fashion became a global industry, and when supermodels became celebrities. He became their go-to artist for endless Vogue covers, published two best-selling books that showcased the artistic possibilities of his work, started his own makeup line, and, as Linda Wells puts it, “achieved what no one in the field had ever achieved.”

But Aucoin struggled with his personal relationships. He had been adopted, and the initial excitement about connecting with his biological parents was dampened when they turned out to be religious and anti-gay. “It was extremely painful," says a friend. He also struggled with his self-image and physical pain, which turned out to be from a rare disorder called acromegaly, which made him extremely tall — he grew to be 6’9” — and elongated his jaw. “Kevyn never saw the beauty in himself,” his sister says at one point in the documentary. “He would see it in others, and bring it out in others."

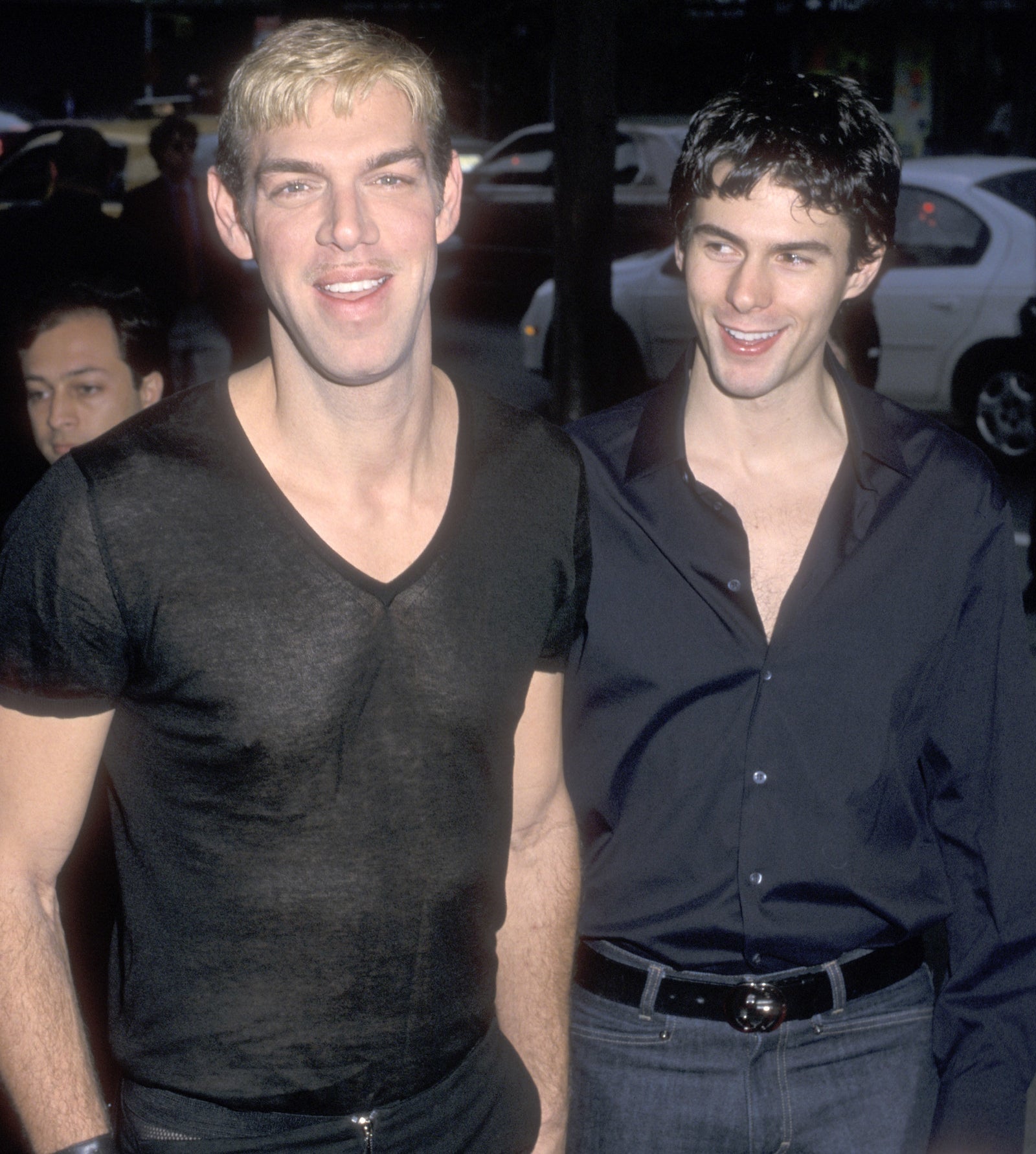

In trying to control his pain, he became addicted to prescription painkillers, and had trouble keeping his professional life on track as the drugs took over. His partner, Jeremy Antunes, left their home, intending it to be a temporary wake-up call for Aucoin, and in the interim Aucoin died of an overdose at 40.

At one point in the film, singer-songwriter Tori Amos makes a poetic point about Aucoin’s decline. “He gave too much credit to those of us who he made beautiful,” she says. “I think he thought, No but we’re friends, I love you, and that’s what he got wrong, because we let him down.” But the documentary doesn’t show Aucoin solely, or even primarily, through the eyes of the celebrity friends who helped make him famous. Instead, we clearly see his private pain on his terms, attested to by those who knew him best.

Aucoin was never afraid to live a public life as a gay man; he and Antunes had a wedding ceremony, years before gay marriage became legal, and the documentary includes video of him calling in to a talk show to complain that Reagan and Bush “didn't care about anybody except white straight men.” But before he died, Aucoin spoke candidly to a friend about the impossibility of overcoming his traumatic childhood and coming to terms with moving through the world as a gay man.

“I've been fighting this my whole life,” he said, “and this thing stays with me my entire life. Everything that I've been through, it just never goes away, and it never will.” In a landscape where much of queer representation still seems to shuttle between the sentimentality of “it gets better” PSAs and the monstrosity of conversion therapy camps, Larger Than Life is a gay man’s story in all its ordinariness — a rare, sensitively rendered portrait of a common yet specifically queer pain that was simply too much to bear.

McQueen is superficially similar to Larger Than Life: Both films trade on the supposed intimacy of home movies, and feature interviews with family members, romantic partners, and close friends; both men died at 40 under tragic circumstances (in McQueen’s case, suicide). But the portrait of McQueen is less nuanced in handling the intricacies of the designer’s life.

“I wasn’t interested in Lee’s sexual preferences whatsoever,” the writer Bonhôte told Queerty, using the name by which friends and family knew McQueen. “That’s Lee’s personal life. It might have in some ways inspired the work, but it didn’t dictate what he did.” Ettedgui, the director, told Vogue that McQueen’s family members “were really happy that we chose to show his work and not the gay clubs and all of that.”

“That’s Lee’s personal life. It might have in some ways inspired the work, but it didn’t dictate what he did.”

McQueen, like Aucoin, was not shy about self-documenting, and we hear his voiceover throughout the film in brief excerpts from a friend’s interviews and exchanges with him. The friend jokingly describes them as “the original documentary on Alexander McQueen: the McQueen tapes.” But the very short snippets from these tapes are often included to make isolated points about his personal life, and the topics he raises are never explored more deeply.

McQueen came from a working-class background in the south of London. His father was a cab driver who assumed that his son would follow in his footsteps by becoming a mechanic. Unlike the clearer picture of Aucoin’s experiences with his family, we hear McQueen, for instance, briefly note that his father would make “jokes” by saying things like “I nearly ran over a bloody queer last night,” but we receive no further insight into how he felt about that. McQueen briefly mentions abuse from a brother-in-law. “In his early years he saw domestic violence,” the sister says, diplomatically.

McQueen became close to his mother, who suggested he look for work as a tailor’s apprentice in Savile Row. He had such a natural flair for tailoring that a mentor recommended he try art school at Central St Martin’s, and from his first fashion show, McQueen’s style became notorious for its dark vision. In that first show, one of the models was styled to look like she had just been raped; McQueen was accused of misogyny, but he saw his work as a commentary on his own experiences with abuse and about (straight) men’s feelings of ownership over women.

His provocative, headline-grabbing style led to his hiring as creative director of Givenchy, and though the brand’s florals and conservative style weren’t to his taste, the perch helped him gain the credibility and money to start his own Alexander McQueen label. A lot of the documentary is devoted to and organized by the repeated cycles of McQueen working on landmark shows. The narrative’s focus on his work trades on the transgressive cachet of the idea that the “darkness” of McQueen’s artistic creations came from his life, and his voice is used often to emphasize that his show’s themes were almost like confessionals. “Everything I do is personal,” he says at one point. “If you wanna know me, just look at my work,” he declares at another. He describes his approach as to “pull these horrors out of my soul and put them on the catwalk.”

Yet the film avoids exploring that personal life and the glaring, and interesting, contradictions that defined it. Art is not direct self-expression, and McQueen’s own identification with women as objects of violence is a reminder that artistic creation involves a lot of projection and transference, combining vulnerability with some degree of cover-up. McQueen’s allusions to experiencing a “sinister” time with sex, for instance, further described as a moment when he was finding himself, are not probed further. (One former employee-boyfriend makes the obvious point that it was hard being in a relationship and working for him.)

Despite McQueen’s outward taste for shocking people — he once told a model to shove her pubic hair in Anna Wintour’s face — he himself underwent the rather extreme measures of gastric bypass and liposuction to make himself fit into conventional ideals of desirability. But these procedures aren’t mentioned in the film, even as it emphasizes his physical transformation from “chubby” Lee to glam Alexander.

Toward the end of the film, a friend says that McQueen’s diagnosis as HIV-positive sent him into “a real depression,” yet the impact of HIV on his life is otherwise glossed over. One can only wonder what McQueen’s diagnosis meant to him as a queer man who came of age at the height of the AIDS crisis, a moment when gay men’s bodies were equated with death and decay in the most punitive ways. These themes were also explored in one of his shows, for instance, where he centered a fat woman’s body covered in moths, as a commentary on the kind of decomposition and corpulent excess that the fashion industry feared.

In contrast, much is made of McQueen’s relationship with Isabella Blow, a fashion scenester who became a close friend during his rise, and eventually became a fashion critic herself. She loved his style — it was her suggestion that he foreground Alexander, his first name, rather than Lee — and he loved her nonjudgmental stance, but he grew weary of her getting credit for his success in the media and distanced himself.

McQueen’s suicide at 40 is connected in the film to paranoia from drugs, and his loneliness after Isabella Blow and his mother died; he killed himself the day after his mother’s death. “Lee didn’t want to face the fact” that he was losing his mother, says his sister. And yet behind that portrait of him as a despondent, saintly son, there is also the even sadder story of someone who finally felt free of his responsibility to a maternal gaze, and who finally pursued life — and death — on his own terms.

In that sense, in following the family’s wishes not to contextualize his struggles, the documentarians unintentionally comment on a theme they could have explored explicitly: what McQueen might have been up against in defining himself while trying to remain close to his family. “I’m not angry with myself,” McQueen says in one of the brief, decontextualized fragments of his voice. “I’m angry at the world.”

But it’s left to the viewers to connect the dots between the anger, the art, and the (gay) man. The filmmakers wanted to focus on his work, not his personal life, but in the end, it's difficult — if not impossible — to separate the two without it making for an incomplete portrait.

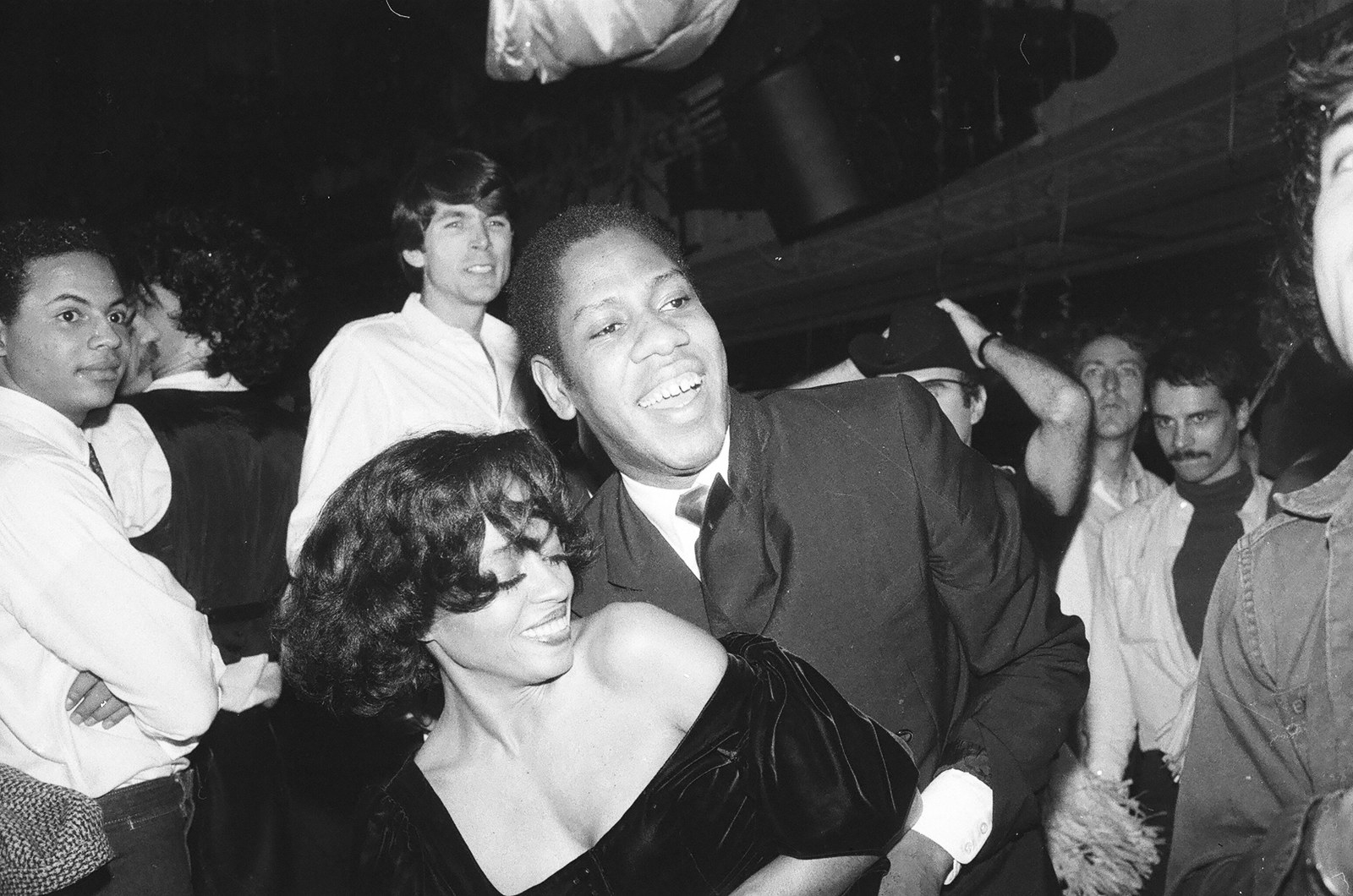

Like Larger Than Life and McQueen, The Gospel According to André is also a kind of bildungsroman, following the way Talley propelled himself from Jim Crow–era North Carolina to New York and transformed himself from a theatrically cape-wearing boy into the iconic editor, friend of Anna Wintour, and pop culture symbol of fabulousness that he became. The film has been critiqued for what it leaves out, but Talley himself sees it as an intimate portrait.

“I’ve opened my heart and my soul and my life,” he said of the documentary. “And I am a very private and shy person, although I come off as a very flamboyant person. I use clothes as armor; clothes are my security blanket and my clothes and outfits are my armor against the world of the chiffon trenches.” Unlike the other two films, which explore the legacies of men whose deaths have given their stories an ending, Talley’s story is still ongoing. Further, Talley — and the documentary — has to grapple not just with how to talk about sexual or gender identity, but also with race.

The film’s story is told largely from the protagonist’s perspective, intercut with quasi–reality show vignettes where he interacts with friends and acquaintances — styling television personality Tamron Hall, visiting actor and Vogue cover girl Isabella Rossellini at her farm — and the film is revealing in its own way about how Talley created that armor.

The film is revealing in its own way about how Talley created his armor.

As a child, he grew up greatly connected to the church, and protected by his grandmother in a world of women, a world that he compares to Truman Capote’s Southern childhood surrounded by aunts. He understood the church as a kind of fashion show, and fashion magazines — and the occasional black models in Vogue — showed him “that there were people who were not racist, who were not judging you for the skin color that you had. That was my most important escape, and that was my world.”

Talley left the South, where he had rocks thrown at him while walking to the library at Duke University, for Brown University in Rhode Island, which gave him “a freedom, a liberation, and propelled me into the world that I know.” Aside from his grandmother, Talley was also very inspired by glamorous white women; he modeled himself after Lady Ottoline Morrell early on, says he learned about the glamour of thrift shop hunting from watching Barbra Streisand, and was eventually mentored by Diana Vreeland at the Costume Institute.

After a receptionist stint at Interview magazine, Talley became the Paris bureau chief for Women’s Wear Daily, where he used his expansive range of references — from expertise about Southern black women’s hats to European romanticism — to write about and help define the reception of fashion luminaries like Yves Saint Laurent and Karl Lagerfeld. His initial stint at Vogue, under Grace Mirabella, was discouraging, as she was dismissive of his ability to make these critical connections.

Wintour, the subsequent editor, appreciated what she calls Talley’s “impeccable” knowledge of fashion history. Seemingly aware of the way Talley has been cast in the public imagination as her sidekick, Wintour goes out of her way to explain that she was not “his protector.” Instead, she says, “I think I learned a lot from him." We see some of his editorial perspective in a memorable layout from his Vogue years in which Talley inverted the imagery of Gone With the Wind by posing Naomi Campbell as a black Scarlett O’Hara, with designers John Galliano and Manolo Blahnik as her servants.

There are myriad references to Talley’s “mannerisms” and “flamboyance” and “theatricality,” and his cultural significance as a black man in fashion who, as one Yale theology professor and friend puts it, defied ideas about black manhood and respectability. But, although the part of the film tracing Talley’s younger years contextualizes his experiences with racism, his fraught position as the lone black person in most of the fashion world he gained entry to isn’t quite a narrative throughline. And Talley doesn’t talk about his identity in terms of gender dissidence or sexuality; as critic Emily Yoshida notes, the word “gay” is not even used until very late in the film.

Throughout his career as a public figure, Talley has rejected the label “gay,” more vaguely alluding to “gay experiences.” That seems to be in part because, as he explains in the film, “I have no love life. I never had a love life; I was busy doing my career.” In describing his Interview magazine/Warhol era with partying at Studio 54, he dismisses the “libertines” who surrounded him and explains that he went for the dancing, not the sex. Fran Lebowitz calls him a “nun,” putting the onus on his own vow of chastity, though he yearningly alludes to white gay friends — like Tom Ford — who found long-term partners.

One of the most vulnerable moments in the film comes when Talley explains that a woman who worked at Saint Laurent during his Paris days used to call him “Queen Kong,” as if he was “a gay ape,” and quickly adds, “I never confronted her. These things I internalized and kept them bottled up.” He tears up, seemingly getting in touch with that pain, though the film quickly cuts to another scene. It is really the only moment that Talley refers to himself as gay, and the fact that it’s framed as an identity projected on him in a punitive way from the outside, where racism and homophobia intersect outside of his control, conveys something about what he’s had to endure.

If questions about gender and sexuality remain mostly unexplored in The Gospel According to André, it seems to be because of Talley’s boundaries rather than, as with the McQueen portrait, the director’s. But it’s hard to say how those factors intersect; Talley was more candid about racism in the industry, and about being dropped by some fashion friends, including Anna Wintour, in articles about the documentary than he was in the documentary itself, which raises questions about how comfortable he felt having his life story in the hands of this particular director. Novack has said that in making the film, “The biggest challenge was establishing trust over time with someone so experienced with crafting images — particularly his own public persona.”

The film begins and ends with Talley conveying the importance of his grandmother. In the final scenes, he sits in a room that was modeled after Diana Vreeland’s famous red room, but it’s also a space, he says, that his grandmother would have felt comfortable in. It’s a telling indication of the tapestry of Talley’s identifications and the way he’s built his identity out of an in-betweenness across racial and gendered models. But it also suggests that for Talley — who, as the director points out, believes in the idea of “radical presence,” or that there is inherent meaning in being in spaces previously denied to people of color — his performance and creation of himself has been one of his greatest works of art.

These three films are revealing not just about the men whose lives they chronicle, but also about the complicated politics involved in telling their stories. In some ways, Aucoin’s portrait appears to be the most complete because, as an openly gay white man with an ultimately supportive family, his life comes closest to what mainstream culture imagines a “full” private life should be. Because his siblings were willing to talk about topics like gender dissidence and sexuality, the film was able to treat these aspects of his life with nuance.

The documentary on McQueen, hampered by limitations the film’s creators and his family imposed, tells an interesting story about the “darkness” of his art, but raises questions about whether this is the way he understood his own life. When we hear such brief snatches of McQueen himself mentioning homophobia in his childhood or, as the directors put it, “the gay clubs,” we can’t help but wonder what was left out. Talley’s own style in telling his life story — certainly a legitimate form of self-representation and opacity — is reproduced in the documentary and arguably offers its own kind of truth about his life and work.

All such documentaries are ultimately interpretations and, especially in the case of Aucoin and McQueen, it is impossible to know how much these men would have wanted to share, or how they saw themselves. Since at least the ’90s, it’s become common knowledge that trying to make queer identity knowable will always be messy and complicated. Some directors, like Isaac Julien in Looking for Langston — a filmic meditation that situates Langston Hughes in a queer black world — more overtly combine the fictional, the artistic, and the biographical in an attempt to stage nonlinear connections and associations even as they acknowledge the impossibility of knowing.

But as mainstream films for a wide audience, these documentaries are forced to take a more straightforward approach. They bring a supposedly objective eye to bear on lives that defy notions of objectivity, focusing on subjects for whom the gaze of culture (and family) has often been a source of pain. It is no surprise that they leave us with as many questions as answers. ●

CORRECTION

McQueen briefly refers to abuse from his brother-in-law in McQueen. An earlier version of this story included a quote from a source that misattributed the abuse to McQueen's father.