Though they’ve been replaced by a battery of buff, blonde pretty boys in the current era of superhero fantasy franchises, there’s still a strain of cultural nostalgia for movies featuring the engorged "hard bodies" of Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger and the martial arts stylings of Steven Seagal and Chuck Norris. Throughout the ’80s and ’90s, in films like Commando and Rambo, Delta Force and Under Siege, these tough guys represented American heroism as they faced off against Soviet dominance in boxing rings and machine-gunned their way across jungles in Central America and Southeast Asia.

And even as those movies lost mainstream appeal, the pugilistic pantheon of brawny Americana they made famous still dots the pop culture landscape in different guises. These men are now controversial Republican politicians, improbable reality television stars, meme factories, and have even been jammed together in hard-body nostalgia franchises, like the Stallone-led The Expendables.

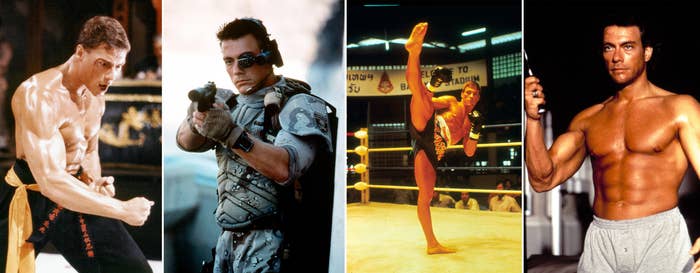

Perhaps less memorable to US audiences than Stallone or Schwarzenegger — but in retrospect more interesting — was the Belgian import Jean-Claude Van Damme, the "Muscles from Brussels.” He didn’t rise to fame playing the kind of America-first roles of Stallone in Rambo or Schwarzenegger in The Terminator. Instead, the French-accented Belgian actor played inexplicably French-accented Americans abroad, in films set in Hong Kong or Thailand. He rose to prominence with cheap martial arts flicks like Bloodsport (1988) and Kickboxer (1989). He peaked in the mid-’90s with higher-budget films like Universal Soldier (1992) and Time Cop (1994), which attempted to slot him into the Stallone- and Schwarzenegger-like roles he never quite pulled off in the United States. Van Damme was always too much: too Euro, too sexy, too revealing, too beautifully choreographed to fit into the one-dimensional action hero fantasies required by American fans, and he disappeared into remainder bins.

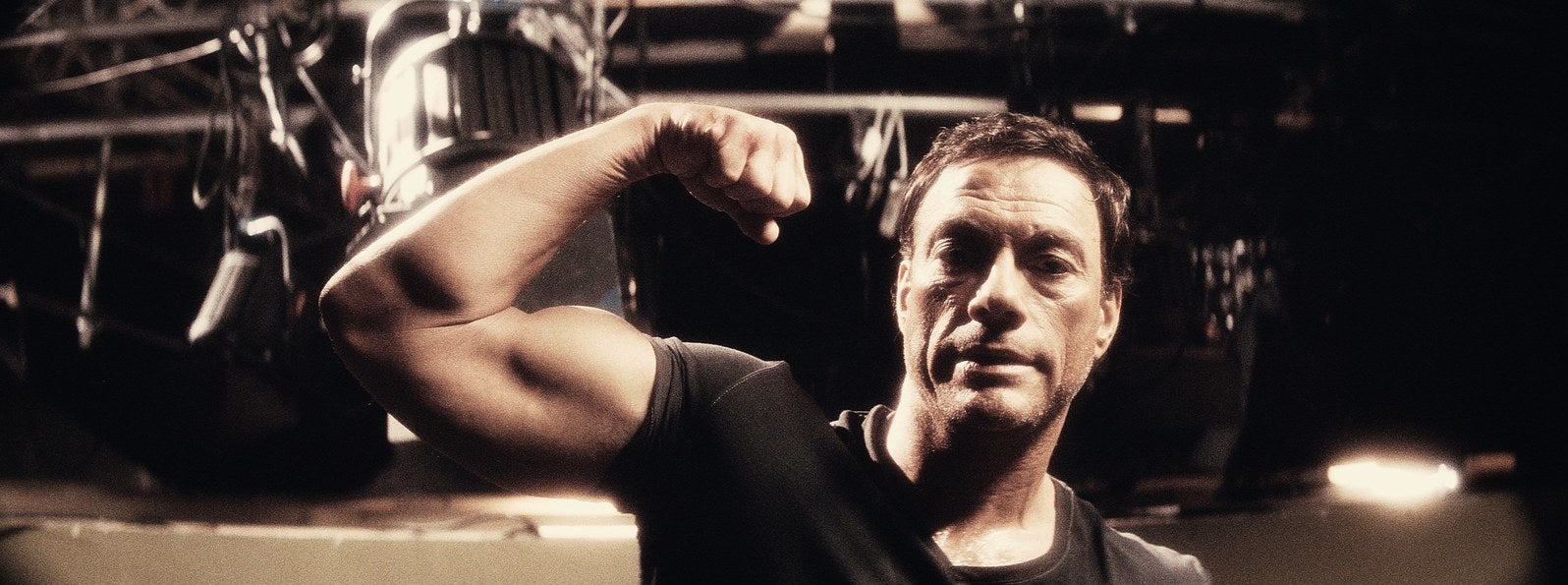

And now, just as he once tried to fit into those American hard-body conventions, Van Damme is looking to ride the new wave of American nostalgia for action films. His first mini comeback in the aughts came about not thanks to a mainstream Hollywood blockbuster, but to a darker 2008 French art house film, JCVD. It combined fictional and real aspects of Van Damme’s personas, as he played a washed-up ’90s action star who returned to his Belgian homeland only to be caught up in a bank robbery where his movie star powers don’t hold up. JCVD wasn’t a commercial success, but it garnered the first great acting reviews of his career.

He’s now back to reprise the role of fading action star in the Amazon series Jean-Claude Van Johnson, which reads as an attempt to extend the shelf life of that movie and put him back on the US map. But once again he’s being slotted into the most bland, mainstream action nostalgia conventions. With Expendables cowriter David Callaham as the showrunner, the show is self-aware about Van Damme’s aging, but doesn’t ultimately explore the cultural implications of the ’80s action hero’s passing or even lean into the specific characteristics that made Van Damme unique.

Stallone and Schwarzenegger seem happy to make jokes about their own aging bodies, though not necessarily about the aging genre they were a part of. Of all these action stars, Van Damme was the closest thing to an outsider looking in, and as such, might seem the best candidate to engage in an insightful critique of both his own movies and others. But while Van Johnson does try to engage in “woke” parody, it misses an opportunity to grapple with the dated tropes — like white Western heroism at the expense of othering other nations and races, and caricatured depictions of women characters — that rendered ‘80s and ‘90s action films culturally problematic and passé. Van Damme is still struggling to find his way into a culture that doesn't like to see their hard bodies in decay — or question what they stood for in the first place.

Of all the ’80s action heroes, Jean-Claude Van Damme had arguably the most multi-layered, complicated image as a European trying to enter into the American consciousness through niche martial arts films. His signature move — that iconic split — required massive strength, but unlike a straightforward punch or bravado-fueled wielding of a machine gun, it carried a tinge of masochism. His balletic splits and roundhouse kicks separated Van Damme from the other action stars; one fan called him the “Fred Astaire of karate.” Unlike Austrian-born Schwarzenegger, the Belgian actor didn’t neutralize his accent with monosyllabic catchphrases and a hyper-macho persona. His foreignness came off as a French lover boy, and, at least to American eyes, his movements — and some memorable bikini briefs — made him a bit of a caricature. He was unusual as an action hero unembarrassed by the erotics of his body.

"I think that Jean-Claude will eventually do the Tom Cruise roles," his agent optimistically told Entertainment Weekly in 1993. His management hoped to sell him as a mainstream lead and that he might potentially transition into other genres like romance and comedy. But, as writer Jess Cagle skeptically notes at the end of the piece, “Even in his new-and-improved packaging, Van Damme is still a gamble. Americans like their action heroes to be just that — heroic defenders of truth and justice and the American way, regardless of where they picked up their accents.”

And Cagle was, evidently, right; Van Damme’s Americanization never quite worked. While Schwarzenegger married into the Kennedys, Van Damme was involved in endless drug and divorce scandals. And the kinds of Reagan-era narratives of rogue heroism that resonated in the ’80s started to lose cultural currency in the triumphalist Clinton ’90s. By then, even Schwarzenegger and Stallone had moved on from the action format — with lighter comedies like Twins (1988) and Kindergarten Cop (1990) or Stallone’s Oscar (1991) — suggesting that it was already too late for the hard-body genre to work as a mainstream star-maker.

Van Damme’s 1994 film Time Cop (which Roger Ebert called a “low-rent Terminator”) topped out at $45 million in the US. And despite being based on a massive video game franchise, 1994’s Street Fighter — which even featured Kylie Minogue in a supporting role — only brought in $33 million domestically on a $35 million budget. The following year, a skeptical Premiere magazine cover story asked, “Will 1995 Be the Year of Jean Claude Van Damme?” But aside from a 1996 spoof playing into his loverboy image on Friends, Van Damme slowly disappeared from mainstream American pop culture. By the aughts, he was consigned to straight-to-video releases.

It was Van Damme’s story of decline that eventually spurred French journalist Fred Benudis, a fan of the actor, to make a documentary about him. Under Van Damme’s Skin aired on French television in 2003, and it was the first step in creating the persona — and narratives — that led to his comeback. The documentary intercuts scenes from Van Damme’s biggest movies with interviews and footage of his surreal existence as a forty-something former movie star living in Los Angeles; he bumps into Lou “the Hulk” Ferrigno at the gym (and comments on his beautiful body), demonstrates a childlike enthusiasm for kickboxing, and holds forth with quasi-deep, rambling philosophizing (about the self-help concept of “awareness”). In the documentary, Van Damme attributes the decline of his stardom to signing up for too many bad movies and to the personal troubles that were endlessly covered by ’90s tabloids: cocaine abuse, multiple marriages and divorces, custody issues, and allegations of domestic violence, which aren’t addressed in the documentary or the 2008 film inspired by it.

Van Damme’s multilayered performance in the documentary led Benudis to write a script, “The King of Belgium,” as a comedy involving Van Damme in a failed bank robbery attempt. French-Tunisian auteur Mabrouk El Mechri then rewrote that script into JCVD, turning it into more of a meta commentary on Van Damme’s career. He felt Van Damme "was a prisoner of what he became," and he wanted his film to "rediscover the man who stands in the shadow of his own image, and explore what that would feel like." But JCVD works less as a cliched look at “the real man” in the shadow of the image and more as a meditation on Van Damme’s hard-body stardom.

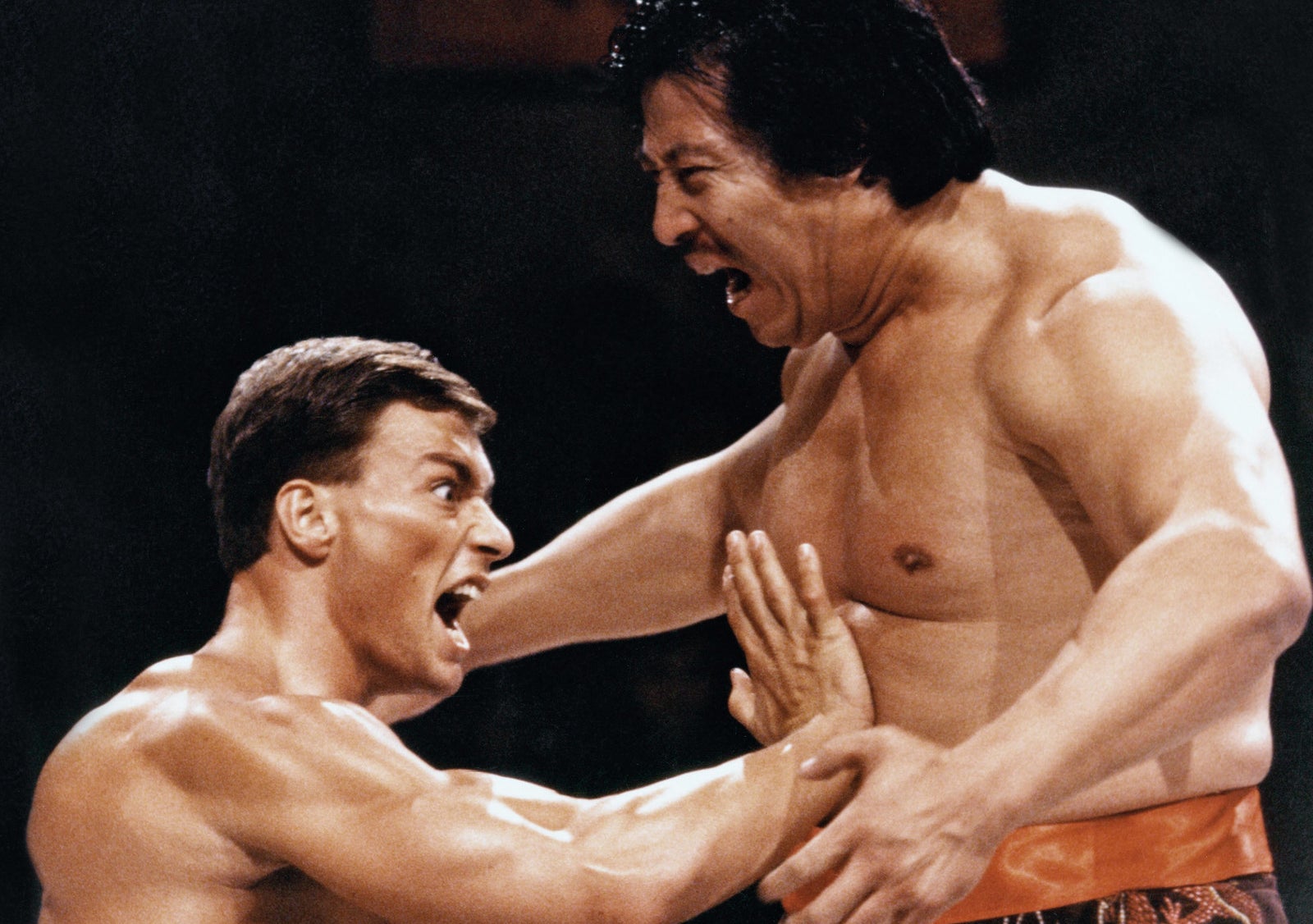

As a European of Arab descent, El Mechri has both an insider and outsider perspective that gives his movie a cultural specificity that’s lacking in the documentary or Van Damme’s Hollywood blockbusters. By locating Van Damme back in Belgium, we get a sense of the meaning of his stardom, not from an American perspective, but as a local Brussels kid gone Hollywood; all the fans he runs into point out that he represents the possibility of leaving their town for global success. The most compelling — and funniest — part of the film is when a video store clerk and a customer, played by a French-Moroccan actor who made news by turning down a stock Arab terrorist role, are watching Chuck Norris’s 1986 film Delta Force. They get into a discussion about the way virtually all hard-body movies, ranging from Delta Force to Mark Wahlberg’s Lone Survivor, turn nonwhite characters (whether Vietnamese or Iraqi) into caricatured bad guys and villains.

Of course, the martial arts movies Van Damme starred in also had their own troubling orientalism. “The not-so-subtle racism of Bloodsport lies in appropriating an Asian genre and Asian locations while populating the picture with bland round-eyes,” Chicago Tribune’s movie critic Dave Kehr noted in 1988. “The Chinese actors are largely relegated to comic relief and snarling villains from the yellow peril school.” The limit of JCVD is that, while it brings up the question of orientalist othering, it doesn’t reckon with the way it structured Van Damme’s own films and stardom, and, while it brings up his womanizing, it doesn’t grapple with domestic violence.

El Mechri felt that JCVD’s blurring of the line between fiction and reality gave Van Damme “a rare and exceptional stage on which to play and to perhaps clear up a few stories about his life and career.” And Van Damme’s acting in JCVD was most praised for a monologue in which he seems to break the fourth wall to talk to the audience directly, and in which he engages in the kind of freewheeling philosophizing of the documentary. But the monologue oddly blames his drug addiction on his love of “a woman” and seems to idealize — or at least smooth over — his mistreatment of his wives.

The film received warm reviews, and Van Damme’s performance was often compared to Mickey Rourke’s comeback in The Wrestler. Like that film, which makes a male weepie out of the decline of an aging wrestler, sentimentalizing his bad parenting and failed marriage, JCVD allowed Van Damme to stage a comeback by reclaiming (and rewriting) his own past. Despite hinting at wider cultural stakes — with its European perspective on “making it” in America, and the orientalized fans speaking back — the film ultimately served to sanitize our understanding of the actor’s personal life. And in playing this version of himself, Van Damme seemed happy simply to ride the aughts wave of American nostalgia that has revived the memories, and in some cases the careers, of his hard-bodied contemporaries.

In 2010, Sylvester Stallone’s nostalgia fest The Expendables brought together aging Hollywood stars ranging from Dolph Lundgren to Mickey Rourke. In the press run-up to the film’s 2010 release, Stallone was asked by the New York Times what killed the action movie star, and his response was “one word: technology.” He believed the kinds of developments that allowed scrawny Tobey Maguire to turn into Spiderman rendered their bodies passé. And indeed, his film completely ignored the kinds of post–Gulf War changes in geopolitics that might affect its narratives, as the story once again placed their characters in throwback ’80s settings, representing racially caricatured South American countries and dictators.

Stallone asked Van Damme to join the cast of the movie, but said that when he approached the actor, “He told me, you should be trying to save people in South Central.” The retort sounds like a semi-woke comment about the film’s outdated racial and nationalistic imaginary — a suggestion that it should look at US inequalities rather than caricaturing other countries. But by 2012, Van Damme signed on to the Expendables sequel, where he played against type as a villain (named Vilain). Critics positively noted his performance; the Boston Globe highlighted his “annoyed, Eurotrashy attitude that could be better leveraged.”

But the overall reception of the film showed that, as the AV Club put it, “the nostalgic kick is gone: It’s a reminder that most of those ’80s actioners were xenophobic and dumb … and that the sight of these old fossils referring to themselves as old fossils is more pathetic than cheekily self-referential.” Rather than using parody to engage with the xenophobia and stupidity of those ’80s films — as 2004’s Team America: World Police did, even with the soundtrack song’s simply idiotic chorus of “America, fuck yeah!” — The Expendables simply recreated the same old tropes, with its stars’ now-aging bodies at the center.

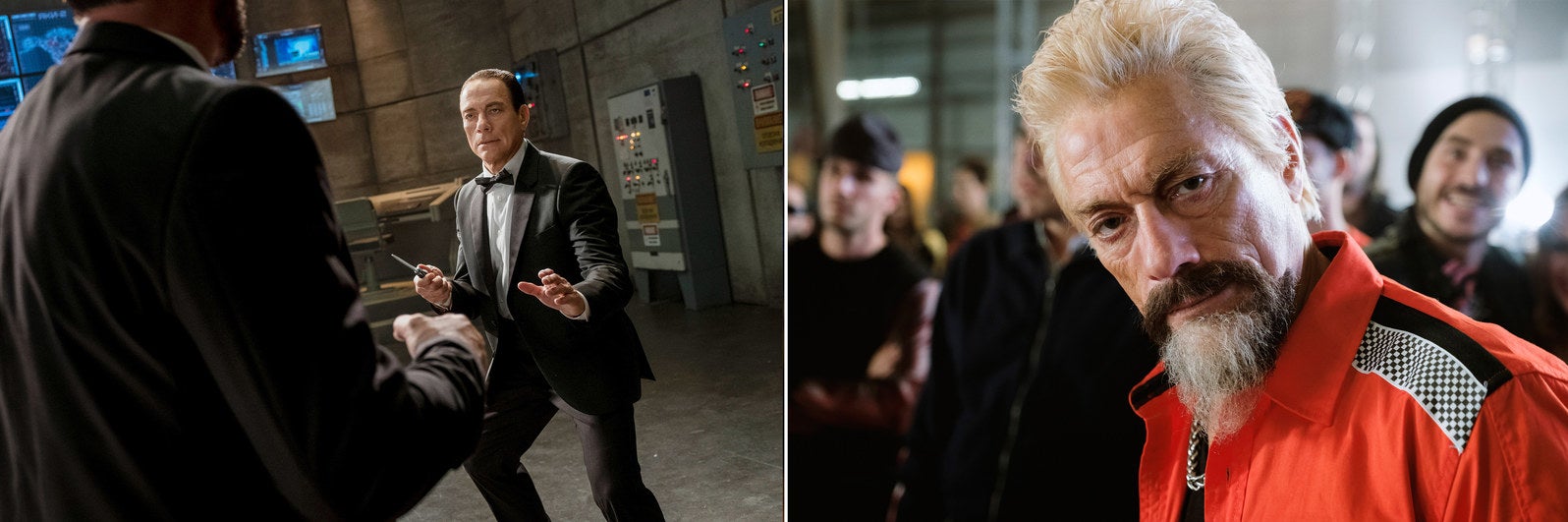

The new Amazon show Jean Claude Van Johnson is directed and written by David Callaham, the original writer of The Expendables, and it does something very similar to that movie: flattens Van Damme through tired self-referential jokes that could be about any other action star, trafficks in the same kind of self-serving nostalgia, and generally fails in its limited attempts to grapple with the genre’s tired tropes and racial caricatures. In this James Bondsian spy spoof, Van Damme is back in LA and plays Van Johnson, another stand-in for himself. The character is retired, both from acting and espionage, having once used his film work as a cover for missions. And from the opening scene in which he wakes up next to a stereotypically “dumb blonde,” it’s clear that there’s a wide range of tropes and stereotypes the show isn’t interested in reconsidering.

The show’s espionage plots are full of conceits about twins and time travel that hint at Van Damme’s movies and that allow him to play multiple versions of himself simultaneously. But, as with the film JCVD, it is when Van Johnson tries to grapple with the cultural questions of hard-body stardom that it’s most potentially interesting — and most disappointing. For example, Van Johnson is working on an action remake of Huckleberry Finn — The Huck — that is meant to parody both the recycling nature of action films and the politics of interracial buddy romances. After Van Johnson tells The Huck’s director that he’s not comfortable with the black character being called “N-word Jim,” the actor gets fired and is replaced by an Asian martial arts star. “We got Johnnie motherfucking Lao,” the director tells him, “this dude is a legend in Thailand.” Lao replies, “I’m Chinese.” The audience is supposed to find his abjection funny.

The films Van Damme starred in conflated different Asian traditions, but in the show he exonerates himself from that kind of ignorance. The jokes are not at his expense, and are only there to make him more sympathetic, especially to Vanessa (Kat Foster), his spy partner and makeup artist, who seems smitten by his wokeness. In other words, the show uses comedy to absolve Van Damme while attempting to gesture to a previous political incorrectness, perhaps as a way of appeasing new audiences. But the jokes never add up to a coherent statement.

Other winking lines about abandoned Blockbusters and a plot involving a microchip seem to line up with Stallone’s suggestion that it’s primarily technological changes that have rendered the stories of yesterday’s action heroes obsolete. But in 2017, hard-body parodies like Van Johnson could do much more meaningful work by questioning the American exceptionalist heroism they played to and helped cement, which is what makes them less and less appealing today.

Perhaps most tellingly, there is a subplot in Van Johnson about Russians who are trying to control the weather and infiltrate the US movie system. In the era of possible Trumpian collusion, these allusions are a reminder of the massive geopolitical transformation the world has undergone even since the era of the first Expendables. Heroes and villains are no longer so easy to align with cartoonish notions of American democracy and backward dictatorships.

There is clearly room, and an appetite, for work fueled by hard-body genre nostalgia. The Expendables franchise has grossed nearly $800 million worldwide. And despite bad reviews, Van Damme’s new show has been written up in affectionate retrospectives and earned him major interviews everywhere from the New York Times to Rolling Stone. But perhaps it’s only when those once marginalized in the ’80s and ’90s action films — non-Americans, women, gay men, people of color — get to rewrite these stories from different angles that we will get a more nuanced (and funny) reckoning with the ways in which the genre’s appeal relied on caricatures.

Van Damme’s campy, complicated image — from his accent to his bikini briefs to his splits — is rich enough to provide plenty of material for a relevant and sincerely (rather than superficially) woke parody of the genre that launched his career. But if those parodies are ever going to be worthwhile, they’ll have to stop landing easy, self-exonerating punchlines and start asking tough questions. ●