Even before its release, Hillary — a new four-part Hulu documentary tracing Hillary Clinton’s life, career, and the 2016 presidential campaign — made headlines for what Clinton had to say about Bernie Sanders. “Nobody likes him. Nobody wants to work with him. He got nothing done,” Clinton says in a teaser released last month. Her comments sparked a big backlash, including boos from Rep. Rashida Tlaib, a Sanders campaign surrogate.

Tlaib’s booing made news because it spoke to an ongoing generational power struggle in the Democratic Party — a clash between Clintonian, pantsuited centrism and insurgent leftist politics that can’t be boiled down to questions about media representation and gender alone. Tellingly, much of the media coverage and social media reactions chastised Tlaib — who later apologized — as an unruly, ungrateful Bernie Bro who should be thankful to Clinton for clearing a path for women in politics, rather than a feminist whose beliefs about class and imperialism are fundamentally at odds with Clinton’s politics.

But if that kerfuffle suggested that this portrait of Clinton might (deliberately) provide some fresh insight into the changing conversation about gender in politics, or the current electoral landscape, no such luck — it turns out she was talking about Sanders in the 2016 election. And there is nothing else that politically provocative in the actual documentary, directed by Nanette Burstein, which premieres today.

The film combines two chronologies, moving back and forth between Clinton’s life story and the 2016 election (including behind-the-scenes campaign footage) in each of the four, one-hour episodes. But it’s something more akin to a glossy and meandering pop star portrait, pitched to resonate with the kind of Clinton fans who might purchase her Book of Gutsy Women, rather than a document of women’s history or cultural analysis. Hillary attempts to stuff her complicated, unique story as a politician and public figure into a conventional narrative about women’s empowerment that has little new to say about either Clinton herself or the history of women in politics.

Writing for Medium in 2017, Natalie Shure cogently diagnosed the way feminist writers in corporate media tend to cover women in politics, including powerful politicians like Clinton and, more recently, Sen. Elizabeth Warren. She notes how articles or profiles about them often overlook any sense of these women’s structural power as politicians and instead treat their political trajectories as celebrity narratives, recasting their “actual record and politics as the inescapably gendered traits of a complicated female character.”

Hillary is like a four-hour version of that kind of storytelling. Moving around from Clinton the controversial icon to Clinton the person, the film attempts to bring together the strands of her life and career through focusing on media coverage, to explain how Clinton has been maligned by the press and provide an intimate portrait beyond the Hillary we’ve seen in the media.

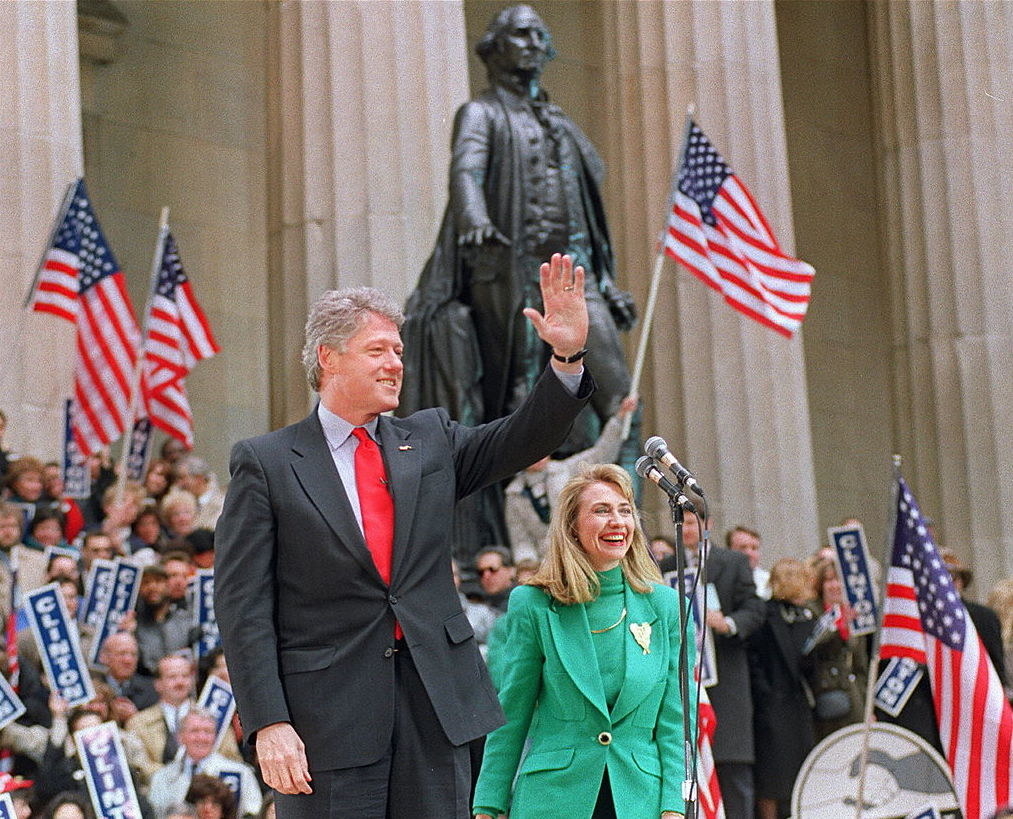

The first episode, “Golden Girl,” combines the launch of Clinton’s presidential candidacy with her early life, from her upbringing as a Republican Goldwater girl in suburban Illinois to her time as first lady of Arkansas. The second episode juxtaposes her becoming the “establishment” candidate for the presidency with her years as first lady in the White House. In the third episode, she becomes, in the words of the episode description, a “global feminist icon” but deals with “setbacks in her marriage.” The fourth episode combines her entry into politics as a senator with the end of the 2016 election.

But the documentary’s attempt to make Clinton into a kind of representative figure of women’s history never fully works, in part because it’s in thrall to her celebrity without analyzing it, and because it never contextualizes her journey outside the way it has already been covered by the media. The people interviewed, for example, are limited to her friends, campaign operatives, and establishment media commentators from the New York Times or Washington Post; there are no academics or historians giving less inside-the-bubble perspectives on Clinton’s public image.

Take, for instance, the segments on her first lady years. The film trots out plenty of schoolmates to testify to Clinton’s charisma and ambition at Yale Law School, and many of them speak about their disappointment that she followed Bill Clinton to Arkansas — where he rose to the governorship while she worked at a corporate law firm — rather than pursue her own political career at the time. (“I followed my heart to Arkansas,” she says.)

The documentary emphasizes the way the media became fascinated by the Yale-educated lawyer’s relationship to the first lady role, as she took on a reformation of the educational system in Arkansas. Many of the journalist talking heads make the point that Clinton was somehow “ahead of her time.”

“I’ve always thought of Hillary as sort of ahead of her time and never quite of her time,” says New York Times reporter Amy Chozick, who covered Clinton through two campaigns and published a book about the experience in 2018. “In the ’90s, there was an element of radicalism to her feminism,” says writer Joe Klein. “She was too right too soon.”

Clinton was not overtly radical; she was in some ways conventional and in some ways out of step with the gendered expectations for white middle-class women of her era.

But in fact, that kind of conventional wisdom about Clinton’s place in “women’s history” occludes more than it illuminates. Clinton was not overtly radical; she was in some ways conventional and in some ways out of step with the gendered expectations for white middle-class women of her era, and that complicated mixture was what made her such a fascinating — and enduring — media figure.

The kind of debates Clinton sparked — about careerism versus motherhood, or taking her husband’s name, or later, dealing with infidelity — were what made her relatable to so many women and part of what made her a celebrity. Those debates were interesting in part because they were specific to the way she was trying to expand the highly gendered first lady role and the role of the campaign spouse.

But while revisiting those controversies may tell us something about Clinton’s celebrity, it doesn’t say all that much about women in the Democratic Party or women in politics at large. There were plenty of women Democrats who came to power on their own terms in the early ’90s, like former Texas governor Ann Richards and Sens. Dianne Feinstein, Barbara Boxer, and Carol Moseley Braun, even as women of color who were deemed too radical were not protected by the Democratic Party. ContextualIzing Clinton’s story with theirs or within the Democratic Party — in the way the recent political documentary Knock Down the House did — might have helped provide a more nuanced understanding of the way gender operates in electoral politics, and how it has changed or not.

The ‘90s media moment was also a very particular era in terms of gender, as recent reconsiderations of tabloid women, including Monica Lewinsky, have made clear. But in the documentary, Bill Clinton’s impeachment, following his affair with Lewinsky, gets framed not as a situation in which the Clinton administration — and Clinton herself — were complicit in the public skewering of a young intern, but in terms of the family drama and her decision to stay in the marriage.

Ultimately, as Hillary moves back and forth in time, it’s a muddled combination of biographical portrait, clichéd media criticism, and banal political commentary that reveals almost nothing new about Clinton — the person, the politician, the celebrity — or the media coverage that has surrounded her for decades.

Despite its intimate title, it’s clear that Hillary doesn’t want to be just a biographical portrait of Clinton. “It's a story not only about me but about the lives of millions of women in our country,” Clinton said while promoting the doc on Good Morning America. But in trying to make her story speak to relatable, supposedly universal issues, Hillary ultimately flattens the cultural and historical uniqueness of Clinton’s story.

Clinton is in some ways unique as a woman celebrity politician, and the fact that the public had already formed a specific understanding about her after years of her being in the public eye, is a complicated — and gendered — aspect of what impacted the 2016 election. But because the documentary seems determined to produce the most sympathetic reading, it never contextualizes such questions outside of Clinton’s very specific journey.

In her interviews looking back at the election, Clinton talks about how she trained herself not to be emotional, and when “you move fast forward to an age where everybody wants to see what your emotions are and how you respond, it’s really a different environment in which we find ourselves now.” The documentary emphasizes the email scandal, replaying seemingly every interview where Clinton addressed it, and the clash of Trump versus Clinton, without really zooming out to analyze the bigger forces — such as race and class politics — that also impacted the election.

In one of the most telling scenes filmed during the 2016 primary, Clinton talks to her campaign policy director Jake Sullivan after a campaign event is disrupted by Black Lives Matter activists and Bernie Sanders supporters. “The turmoil, and disillusionment and discouragement, and anger and all that, we gotta figure out what it actually means in order to deal with it better, don't you think?” she says, sounding earnestly out of touch. “I worry that there's an underlying vitriol in some percentage of Bernie supporters,” says the policy director, seemingly dismissing the message behind their objections.

In trying to make her story speak to relatable, supposedly universal issues, Hillary ultimately flattens the cultural and historical uniqueness of Clinton’s story.

The film ends hopefully, after Clinton’s loss in 2016; we see moving behind-the-scenes footage before her concession speech, where she addressed little girls everywhere. It emphasizes the January 2017 Women’s March and an uptick in the number of women running for office and being elected, including Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and her fellow congressional “Squad” members.

There is no acknowledgment of the fact that in real life, it wasn’t the pro-Clinton Democratic political machine that recruited and helped most of the Squad run for office; it was groups like the progressive splinter group Justice Democrats, whose founders include former Bernie Sanders campaign staffers. Or the fact that more white women voted for Trump than they did for Clinton. Narrative complications like that are beyond the scope of the kind of power this particular film is interested in analyzing.

In some ways, the controversy around Hillary so far has been a more interesting commentary on contemporary gender politics and Clinton’s place in history than anything in the film itself. In recent interviews, Clinton has continued to emphasize the role of gender in the media (rather than policy) in her commentary on the 2020 primary and Sanders in particular, highlighting the “online Bernie Bros and their relentless attacks on lots of his competitors, particularly the women.” Clinton, after the backlash to her comments about Sanders in the documentary, jokingly tweeted: “I thought everyone wanted my authentic, unvarnished views!” — still framing her own politics, and the public’s reaction to her, almost solely in terms of authenticity and likability.

In the years since Clinton ran for president, the conversation around gender and women in politics has become more complex — and more interesting — than the one she seems to still be having. Throughout the 2020 Democratic primary, many writers have examined the question of sexism and its effects on women candidates, almost all of whom have now dropped out of the race. But critics have also interrogated how some of the centrist women of the Democratic Party, like Amy Klobuchar, appealed precisely for the ways they exercise power in traditionally capitalist ways. Both Klobuchar and Kamala Harris fielded questions about their records as prosecutors.

Much of the coverage of Warren ending her presidential campaign has focused on gender, but various postmortems also debate the ways in which her retreat from Medicare for All and reversal on super PAC funding impacted her chances. In many ways, the broader cultural conversation about gender in politics has moved away from simplistic, single-vector analysis; this documentary hasn’t.

At this point, media-friendly narratives that reduce political divides to questions of identity, specifically gender politics that pit white women against white men, like Hillary or Warren versus Bernie Bros, don’t tell us anything new — except the degree to which sexism is still imagined as something that only happens to middle-class straight white women. And limiting an analysis of any political figure to those well-worn tropes inevitably obscures other deep divides around imperialism, class, and race.

Hillary could have been a better film if it had contextualized Clinton’s life, legacy, and celebrity in more honest and nuanced ways. By retelling the same stories about Clinton and her career that we've already heard many times, from her and others, it dwells on the past without telling us much at all about our political present — or future. ●