The journalists at BuzzFeed News are proud to bring you trustworthy and relevant reporting about the coronavirus. To help keep this news free, become a member and sign up for our newsletter, Outbreak Today.

As health professionals are swamped by coronavirus cases, the graduating class of 2020 health care workers has been put on hold, forced to watch without being able to help.

The coronavirus hit as tens of thousands of medical students were about to become doctors, and well over 100,000 nursing students were about to become nurses. They are done with or are finishing years of schooling, and politicians have vowed to get them into the workforce as early as possible.

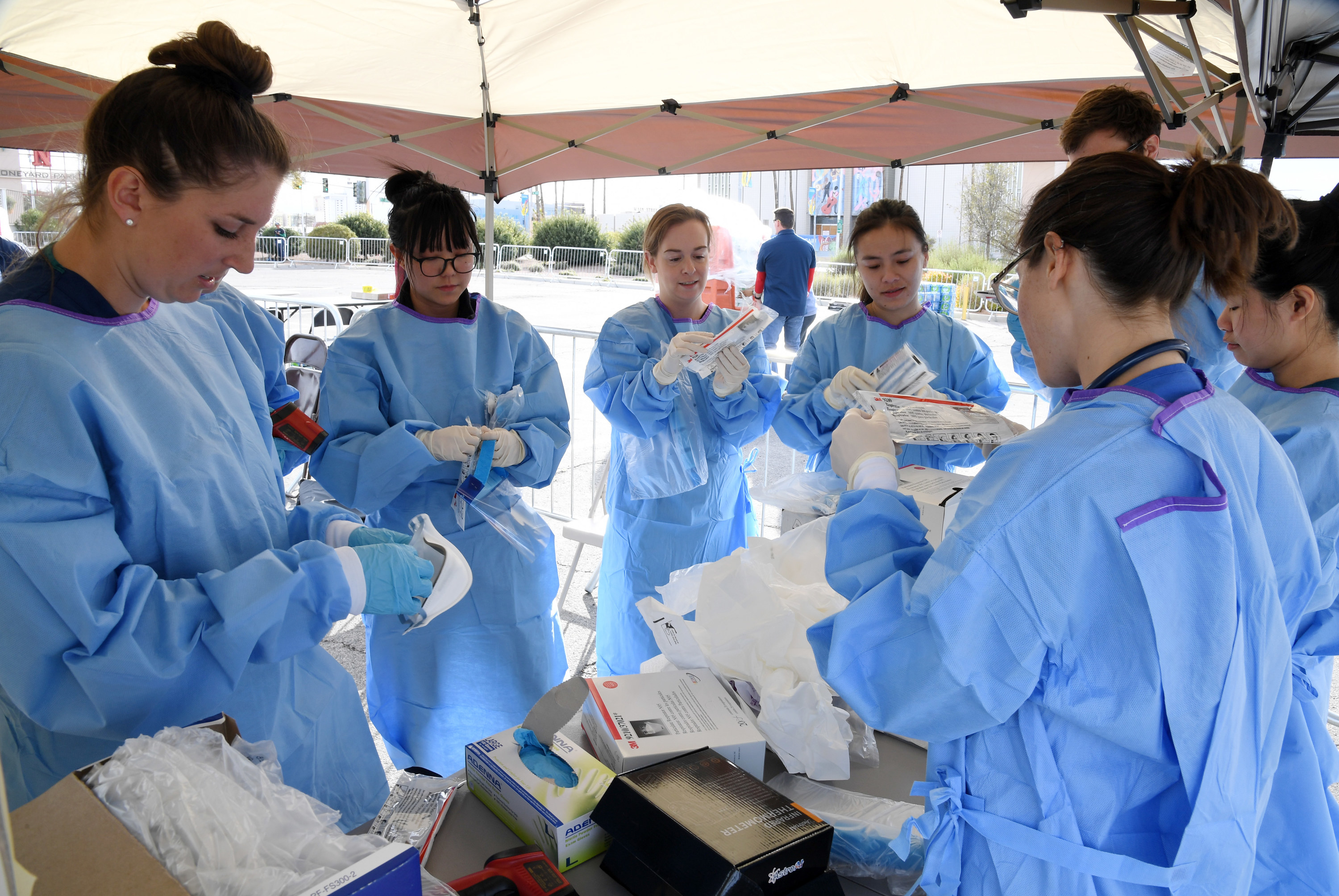

But the reality is largely the opposite. Students have been ordered out of hospitals to comply with social distancing. Since mid-March the American Association of Medical Colleges has strongly urged that med students not be allowed to directly treat patients, to prevent further spread of the coronavirus. Clinical work ground to a halt.

Most students are not seeing their starting dates moved up. Instead, they’re at home isolating and waiting, like everyone else. Only they know that after two agonizing months of waiting, they will be thrown to the front lines of the coronavirus response.

Through interviews and online submissions to BuzzFeed News, medical and nursing students overwhelmingly expressed two contrasting feelings: desire to help and fear of what that help would mean.

“Sitting at home and not doing anything is kind of a helpless feeling. Personally I just feel very low because I know exactly what they need and I know that I could help them, but I don’t have the clearance,” said Danielle, a nursing student in Sacramento, California, who asked that her last name not be used.

But students still have real concern about being thrown into chaotic hospital environments that are dealing with supply problems. They’re well aware of the lack of personal protective equipment, brutal working conditions, and wrenching choices.

“We are all afraid,” said Danielle. "If you’re not afraid, you’re either lying to yourself or you do not fully understand the implications this virus has.”

Many nursing students were sent home when they were on their way to completing mandatory clinical hours. Danielle was pulled out of hospital work on March 9, costing her 120 hours of in-hospital training she needed to graduate. She said her class has been given no guidance on whether those criteria will be lifted.

It’s a case of being so close and yet so far. The students were put on hold less than a month before graduation but now don’t know how it may affect their careers. “In our minds, we are essentially nurses already,” said Danielle. “Seeing everything unfold and the conditions that these nurses are going through, they need our help.”

There has been a lot of talk about getting graduating students into the workforce immediately, but for most grads, the logistics make this difficult, or even unrealistic.

One obstacle is simple geography. The typical class of 2020 med student right now is done or finishing their coursework, set to graduate in mid-May, and start work by mid-late June. But the internship process is a lottery that matches future doctors with hospitals across the country.

On top of moving, they need to complete licensing exams before they can practice medicine. They need to be set up with health insurance and malpractice insurance and everything else that comes with getting someone onto a hospital’s payroll. It’s a multistep process involving medical schools, state oversight bodies, and workplaces that is not easy to fast-track. A school can move up its graduation date, but the grads still wouldn’t be able to work the next day.

There have been limited successes. At New York University, dozens of students volunteered to graduate early and begin working at hospitals affiliated with the university. Oregon Health and Science University managed to get some grads into the workforce months early. But this applied to only five students in the graduating class who were matched with OHSU facilities, where they had already been doing placements.

There is also a widespread sense of personal loss. Med students are losing out on what was supposed to be their one period of reprieve between years of intense schooling and 80-hour-per-week work residencies. April and May are the slow months when people go on long-planned vacations, hold weddings, and see their friends for the last time before they head out to hospitals across the country. None of that can happen now.

“Some of us will never see our friends again because of this,” said Angela Bailey, a graduating University of Michigan medical student. “All those celebrations and all those big final moments that signify to people ‘I am now going to be a doctor’ are gone.”

Some students expressed a tinge of guilt for mourning this lack of closure at a time of so much tragedy. Bailey described the mood among her peers as feeling paralyzed. They’re at home, unable to work. But at the same time they know that in as little as two months they’ll be personally tackling a major public health emergency.

Roles are shifting as well. Bailey was supposed to be a surgical resident, but with elective surgeries canceled for the foreseeable future, she is preparing to essentially be an internal medicine resident. But when the coronavirus outbreak subsides, she expects the system to be slammed with delayed surgeries.

While she waits she has been volunteering with an international student group, helping out in ways that don’t require human-to-human contact. These include answering the phone lines for hospitals and making prenatal phone checkups. “We have been able to help a little bit there, but it’s just a weird time. It’s a really weird time,” she said.

There is also the tricky issue of physically moving. Alex Kokaly is graduating from the University of Michigan Medical School and moving to Southern California to start his internship at UCLA. He took an extra year of school to get a master's, meaning many of his former classmates are currently in their first year on the job.

“They’re all describing the chaos and how they don’t have enough personal protective equipment, all the things they’re dealing with and all the stress and anxiety they’re under,” he said. “That’s making me stressed because I know in a couple months that’s going to be my job on the front lines. I’m excited for it, but at the same time I’m hoping that by June these shortages are all resolved.”

First he’s got to get there. Most graduates end up working in different states or cities than where they went to school. That means moving all your stuff and taking flights at a time you’re supposed to be avoiding human contact.

There is a widespread urge among graduates to start doing something to help. But until their internships start, there’s not much for them to do but wait. Kokaly’s friends who live across the street canceled their wedding scheduled for next week. He’s finished his coursework but still has to wait six more weeks to get the letters after his name.

While stuck at home, he’s passing time with the new Animal Crossing game on Nintendo Switch, which has blown up in popularity during the pandemic. Its gameplay involves exploring a deserted island and completing simple tasks like fishing, gardening, and building furniture. He joked that it helps to keep him sane.

“It’s a world I can control,” said Kokaly. “Which is nice right now.”