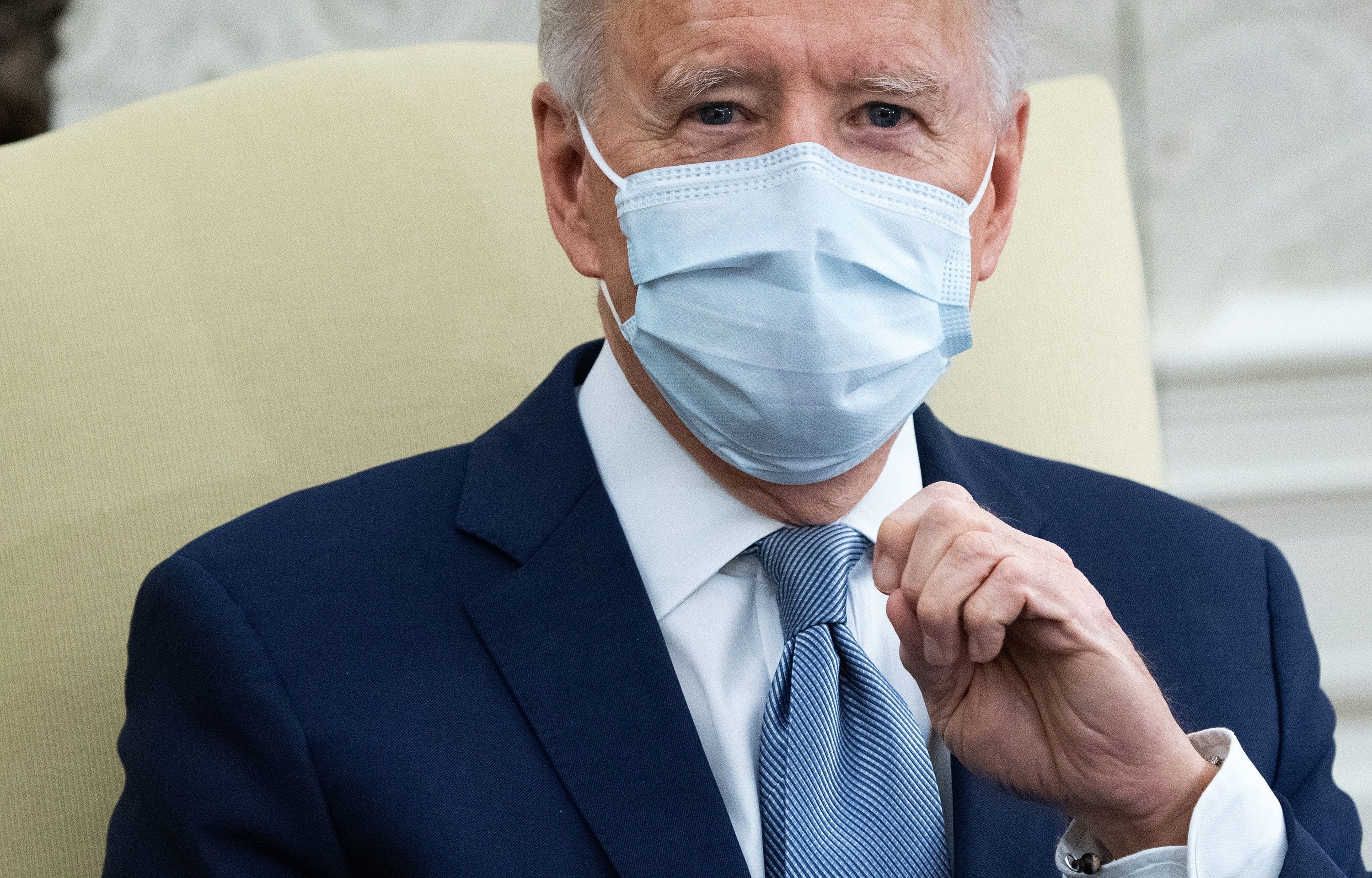

WASHINGTON — A group of Republican senators left a two-hour White House meeting with President Joe Biden on Monday evening with no deal for a new COVID aid package but expressing optimism that one is in reach.

Biden is facing the first major test of his plan to win over some Republicans to back his agenda. The two sides remain miles apart; the group of 10 Republicans is proposing an aid package valued at less than one-third of what the president wants.

“I wouldn’t say that we came together on a package tonight. No one expected that in a two-hour meeting,” said Sen. Susan Collins on Monday night. She nonetheless called it an “excellent meeting” that was “very productive” and said the two sides will continue to talk.

Biden is pushing a $1.9 trillion COVID relief package that includes $1,400 checks for most Americans, as well as an additional $400 per week in federal unemployment benefits through September 2021.

The Republican group is meanwhile proposing an approximately $600 billion package that includes $1,000 checks for a smaller number of people, plus an additional $300 per week in unemployment benefits until the end of June.

Democrats have widely rejected the proposal as inadequate and a nonstarter. “We can’t keep jumping from cliff to cliff every few months,” said Sen. Ron Wyden. “An extension of benefits for at least six months is essential.”

The White House put out a statement late Monday describing the meeting as productive but also threatening to go it alone without Republicans unless they agree to substantially more aid. “[Biden] will not slow down work on this urgent crisis response, and will not settle for a package that fails to meet the moment,” the statement said.

Biden needs 10 Republican senators on board for any bill to pass the Senate through normal methods. But congressional Democrats on Monday started a special process known as budget reconciliation that would allow just the simple Democratic majority in the Senate to pass a bill. The catch is that there is only one budget reconciliation chance for each year, and it only applies to budget items.

It is essentially a rare chance for Democrats to bypass a Republican filibuster and pass a bill without compromising. But using reconciliation to pass COVID aid now would mean future bills would need bipartisan support, potentially blocking Democrats’ path to change on high-priority issues.

During the Trump era, Republicans used budget reconciliation as a once-per-year vehicle for ambitious, partisan legislation that could never pass otherwise. Their failed attempt to repeal the Affordable Care Act was through budget reconciliation. Their tax bill, Trump’s most prominent legislative accomplishment, was passed by Republican votes alone through budget reconciliation.

Now Democrats want to return the favor. Unless they abolish the legislative filibuster in the Senate and grant themselves the power to pass a bill by a simple majority — an option that currently has too much internal resistance — reconciliation is their only shot to override Republican obstruction. Members are already pushing for it to be used liberally and enact policies such as a $15 federal minimum wage.

Over 100 Democratic members cosigned a letter to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi over the weekend demanding that the reconciliation package include a pathway to citizenship for DREAMers, immigrants under the Temporary Protected Status program, and essential immigrant workers.

But Democrats have the slimmest majority possible in the Senate — 50 out of 100 seats with Vice President Kamala Harris breaking ties in their favor — and the larger and more ambitious the bill becomes, the harder it becomes to get everyone on board. All it takes is a single Democratic senator to object to a policy for it to have to be excluded from the reconciliation bill.