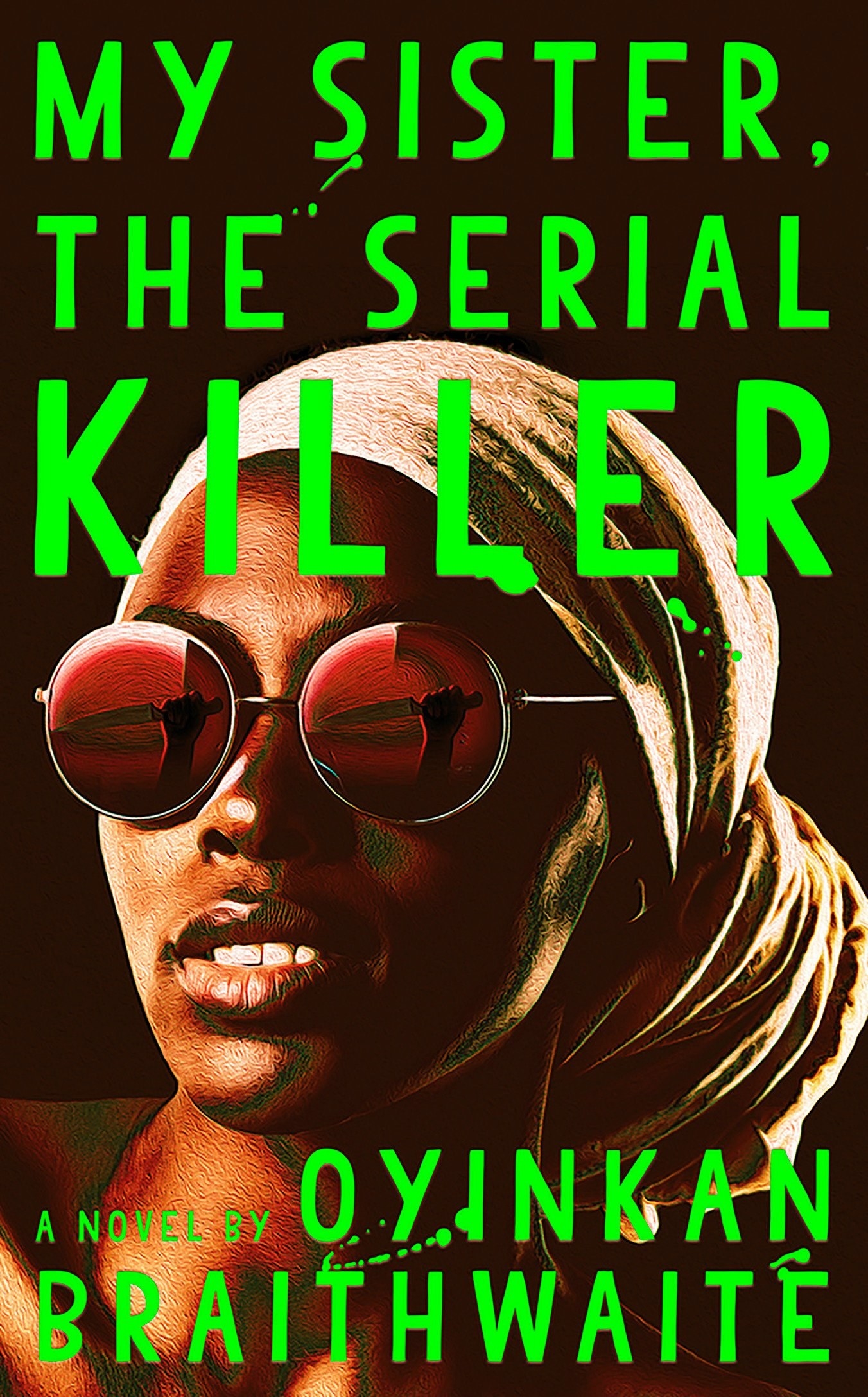

We're so excited to announce My Sister, the Serial Killer as this month's pick for the BuzzFeed Book Club! Join us as we dive into the book — posing questions, sharing opinions, and interacting directly with author Sigrid Nunez. More info here.

[Days after Ayoola killed her boyfriend — her third murder — and called on her sister to help hide the body and clean the mess, the sisters discover the search for Femi is gaining traction.]

#FemiDurandIsMissing has gone viral. One post in particular is drawing a lot of attention — Ayoola’s. She has posted a picture of them together, announcing herself as the last person to have seen him alive, with a message begging anyone, anyone, to come forward if they know anything that can be of help.

She was in my bedroom when she posted this, just as she is now, but she didn’t mention what she was up to. She says it makes her look heartless if she says nothing; after all, he was her boyfriend. Her phone rings and she picks it up.

“Hello?”

Moments later she kicks me.

“What the—?”

It’s Femi’s mother, she mouths. I feel faint; how the hell did she get Ayoola’s number? She puts the phone on loudspeaker.

“...dear, did he tell you if he was going to go anywhere?”

I shake my head violently.

“No, ma. I left him pretty late,” Ayoola replies.

“He was not at work the next day.”

“Ummm . . . sometimes he used to jog at night, ma.”

“These days, you look at me like I’m a monster.”

“I know, I told him, I told him all the time it was not safe.” The woman on the line starts to cry. Her emotion is so strong that I start to cry too — I make no sound, but the tears I have no right to burn my nose, my cheeks, my lips. Ayoola starts crying too. Whenever I do, it sets her off. It always has. But I rarely cry, which is just as well. Her crying is loud and messy. Eventually, the sobs turn to hiccups and we are quiet. “Keep praying for my boy,” the woman says hoarsely, before hanging up.

I turn on my sister. “What the hell is the matter with you?”

“What?”

“Do you not realize the gravity of what you have done? Are you enjoying this?” I grab a tissue and hand it to her, then take some for myself.

Her eyes go dark and she begins to twirl her dreadlocks.

“These days, you look at me like I’m a monster.” Her voice is so low, I can barely hear her.

“I don’t think you’re—”

“This is victim shaming, you know...”

Victim? Is it mere coincidence that Ayoola has never had a mark on her, from any of these incidents with these men; not even a bruise? What does she want from me? What does she want me to say? I count the seconds; if I wait too long to respond, it will be a response in itself, but I’m saved by my door creaking open. Mum wanders in, one hand pinned to her half-formed gèlè.

“Hold this for me.”

I stand up and hold the part of the gèlè that is loose.

She angles herself to face my standing mirror. Her miniature eyes take in her wide nose and fat lips, too big for her thin oval face. The red lipstick she has painted on further accentuates the size of her mouth. My looks are the spitting image of hers. We even share a beauty spot below the left eye; the irony is not lost on me. Ayoola’s loveliness is a phenomenon that took my mother by surprise. She was so thankful that she forgot to keep trying for a boy.

“I’m going to Sope’s daughter’s wedding. The both of you should come. You might meet someone there.”

“No, thank you,” I reply stiffly.

Ayoola smiles and shakes her head. Mum frowns at the mirror.

“Korede, you know your sister will go if you do; don’t you want her to marry?” As if Ayoola lives by anyone’s rules but her own. I choose not to respond to my mother’s illogical statement, nor acknowledge the fact that she is far more interested in Ayoola’s marital fate than in mine. It is as though love is only for the beautiful.

After all, she didn’t have love. What she had was a politician for a father and so she managed to bag herself a man who viewed their marriage as a means to an end.

The gèlè is done, a masterpiece atop my mother’s small head. She cocks her head this way and that, and then frowns, unhappy with the way she looks in spite of the gèlè, the expensive jewelry and the expertly applied makeup.

Ayoola stands up and kisses her on the cheek. “Now, don’t you look elegant?” she says. No sooner is it said than it becomes true — our mother swells with pride, raises her chin and sets her shoulders. She could pass for a dowager now at the very least. “Let me take a picture of you?” Ayoola asks, pulling out her phone.

Mum strikes what seems like a hundred poses, with Ayoola directing them, and then they scroll through their handiwork on the screen and select the picture that satisfies them — it is one of my mum in profile with her hand on her hip and her head thrown back in laughter. It is a nice picture. Ayoola busies herself on the phone, chewing on her lip.

“What are you doing?”

“Posting it on Instagram.”

“Are you nuts? Or have you forgotten your previous post?”

“What’s her previous post?” interjects Mum.

I feel a chill go through my body. It has been happening a lot lately. Ayoola answers her.

“I... Femi is missing.”

“Femi? That fine boy you were dating?”

“Yes, Mum.”

“Jésù ṣàánú fún wa! Why didn’t you tell me?”

“I... I... was in shock.”

Mum rushes over to Ayoola and pulls her into a tight embrace.

“I’m your mum, you must tell me everything. Do you understand?”

“Yes, ma.”

But of course she can’t. She can’t tell her everything.

I am sitting in my car, fiddling with the knob, switching between channels because there is nothing else to do. Traffic plagues Lagos city. It is only 5:15 a.m. and my car is one among many packed tightly on the road, unable to move. My foot is tired of tapping on and off the brake.

I look up from the radio and I inadvertently meet the eye of one of the LASTMA officials lurking around the line of cars, watching out for his next hapless victim. He sucks in his cheeks, frowns and walks toward me.

My heart drops to the floor, but there is no time to pick it back up. I tighten my fingers around the wheel to still the tremor in my hand. I know this has nothing to do with Femi. It can’t have anything to do with Femi.

Lagos police are not even half that efficient. The ones tasked with keeping our streets safe spend most of their time ferreting out money from the general public to bolster their meager salary. There is no way they could be on to us already.

Besides, this man is LASTMA. His greatest task, his raison d’être: to chase down individuals who run a red light. At least, this is what I tell myself as I begin to feel faint.

The man knocks on my window. I wind it down a few inches — enough to prevent angering him, but not enough for his hand to slip through and unlock my door.

I cannot draw attention to myself right now, not while I’m driving the car that transported Femi to his final resting place.

He rests his hand on my roof and leans forward, as though we were two friends about to have a casual tête-à-tête. His yellow shirt and brown khakis are starched to an inch of their life, so much so that even the strong wind is unable to stir the fabric. An orderly uniform is a reflection of the owner’s respect for his profession; at least, that’s what it is supposed to mean. His eyes are dark, two wells in a vast desert — he is almost as light as Ayoola. He smells of menthol.

“Do you know why I have stopped you?”

I am tempted to point out that it is the traffic that has stopped me, but the futility of my position is all too clear. I have no way to escape.

“No, sir,” I reply as sweetly as I can. Surely if they were on to us, it’s not LASTMA that they would send, and they wouldn’t do it here. Surely...

“Your seat belt. You are not wearing your seat belt.”

“Oh...” I allow myself to breathe. The cars in front of me inch forward, but I am forced to stay in place.

“License and registration, please.” I am loath to give this man my license. It would be as foolhardy as allowing him to enter my car — then he would call the shots.

I don’t answer immediately, so he tries to open my door, grunting when he finds it locked. He stands up straight, his conspiratorial manner flung away. “Madam, I said license and registration!” he barks.

On a normal day, I would fight him, but I cannot draw attention to myself right now, not while I’m driving the car that transported Femi to his final resting place. My mind wanders to the ammonia blemish in the boot.

“Oga,” I say with as much deference as I can muster, “no vex. It was a mistake. E no go happen again.” My words are more his than mine. Educated women anger men of his ilk, and so I try to adopt broken English, but I suspect my attempt betrays my upbringing even more.

“This woman, open the door!”

Around me cars continue to press forward. Some people give me a look of sympathy, but no one stops to help.

“Oga, please let’s talk, I’m sure we can reach an understanding.” My pride has divorced itself from me. But what can I do? Any other time, I would be able to call this man the criminal that he is, but Ayoola’s actions have made me cautious. The man crosses his arms, dissatisfied but willing to listen. “I no go lie, I don’t have plenty money. But if you go gree—”

“Did you hear me ask for money?” he asks, fiddling once again with my door handle, as though I’d be silly enough to unlock it. He straightens up and puts his hands on his hips. “Oya park!”

I open my mouth and shut it again. I just look at him.

“Unlock your car. Or we go tow am to the station and we go settle am there.” My pulse is thumping in my ears. I can’t risk them searching the car.

“Oga abeg, let’s sort am between ourselves.” My plea sounds shrill. He nods, glances around and leans forward again.

“Wetin you talk?”

I bring 3,000 naira out of my wallet, hoping it is enough and that he will accept it quickly. His eyes light up, but he frowns.

“You are not serious.”

“Oga, how much you go take?”

He licks his lips, leaving a large dollop of spittle to glisten at me. “Do I look like a small pikin?”

“No, sir.”

“So give me wetin a big man go use enjoy.”

I sigh. My pride waves me goodbye as I add another 2,000 to the money. He takes it from me and nods solemnly.

“Wear your seat belt, and make you no do am again.”

He wanders off, and I pull my seat belt on. Eventually, the tremors still.

A man enters the hospital and makes a beeline for the reception desk. He is short, but he makes up for that in girth. He barrels toward us, and I brace myself for the impact.

“I have an appointment!”

Yinka grits her teeth and offers him her best smile.

“Good morning, sir, can I take your name?”

He tosses her his name and she checks the files, thumbing through them slowly. You can’t rush Yinka, but she slows down intentionally when you push her buttons. Soon the man is tapping his fingers, then his feet. She raises her eyes and peers at him through her lashes, then lowers them again and continues her search. He starts to puff up his cheeks; he is about to explode. I consider stepping in and diffusing the situation, but a yelling from a patient might do Yinka some good, so I settle back into my seat and watch.

My phone lights up and I glance at it. Ayoola. It is the third time she has called during my shift, but I am not in the mood to talk to her. Maybe she is reaching out because she has sent another man to his grave prematurely, or maybe she wants to know if I can buy eggs on the way home.

Either way, I’m not picking up.

“Ah, here it is,” Yinka cries, even though I have seen her examine that exact file twice and continue her search. He breathes out through his nostrils.

“Sir, you are thirty minutes late for your appointment.”

“Ehen?”

It is her turn to breathe out.

Maybe she is reaching out because she has sent another man to his grave prematurely, or maybe she wants to know if I can buy eggs on the way home.

This morning is quieter than usual. From where we sit, we can see everyone in the waiting area. It is shaped like an arc, with the reception desk and sofas facing the entrance and a large-screen TV. If we dimmed the lights, we would have ourselves a personal cinema. The sofas are a rich burgundy color, but everything else is devoid of color. (The decorator was not trying to broaden anyone’s horizons.) If hospitals had a flag it would be white — the universal sign for surrender.

A child runs out of the playroom to her mum and then runs back in. There is no one else waiting to be attended to except the man who is right now getting on Yinka’s nerves. She sweeps a curl of Monrovian hair from her eyes and stares at him.

“Have you eaten today, sir?”

“No.”

“Okay, good. According to your chart, you haven’t had a blood sugar test in a while. Would you like to have one?”

“Yes. Put it there. How much is it?” She tells him the price, and he hisses.

“You are very foolish. Abeg, what do I need that for? You people will just be calling price anyhow, as if you are paying someone’s bill!”

Yinka glances my way. I know she is checking if I am still there, still watching her. She is recalling that if she steps out of line she will be forced to listen to my well-rehearsed speech about the code and culture of St. Peter’s. She smiles through clenched teeth.

“No blood sugar test it is then, sir. Please take a seat, and I will let you know when the doctor is ready to see you.”

“You mean he is not free now?”

“No. Unfortunately you are now” — she checks her watch — “forty minutes late, so you’ll have to wait till the doctor has a free appointment.”

The man gives a terse shake of his head and then takes his seat, staring at the television. After a minute he asks us to change the channel. Yinka mutters a series of curses under her breath, masked only by the occasional sounds of delight from the child in the sunny playroom and the football commentary from the TV.

There is music blasting from Ayoola’s room. She is listening to Whitney Houston’s “I Wanna Dance with Somebody.” It would be more appropriate to play Brymo or Lorde, something solemn or yearning, rather than the musical equivalent of a packet of M&M’S.

I want to have a shower, to rinse the smell of the hospital’s disinfectant off my skin, but instead I open the door. She doesn’t sense my presence — she has her back to me and is thrusting her hips from side to side, her bare feet stroking the white fur rug as she steps this way and that. Her movements are in no way rhythmical; they are the movements of someone who has no audience and no self-consciousness to shackle them. Days ago, we gave a man to the sea, but here she is, dancing.

I lean on the door frame and watch her, trying and failing to understand how her mind works. She remains as impenetrable to me as the elaborate “artwork” daubed across her walls. She used to have an artist friend, who painted the bold black strokes over the whitewash. It feels out of place in this dainty room with its white furniture and plush toys. He would have been better off painting an angel or a fairy. At the time, I could tell that he hoped his generous act and his artistic talents would secure him a place in her heart, or at the very least a place in her bed, but he was short and had teeth that were fighting for space in his mouth. So all it got him was a pat on the head and a can of Coke.

She starts to sing; her voice is off-key. I clear my throat. “Ayoola.”

She turns to me, still dancing; her smile spreads.

“How was work?”

“It was alright.”

“Cool.” She shakes her hips and bends her knees. “I called you.”

“I was busy.”

“Wanted to come and take you out for lunch.”

“Thanks, but I normally eat lunch at work.”

“Okay o.”

“Ayoola,” I begin again, gently.

“Hmmm?”

“Maybe I should take the knife.”

She slows her movements, until all she is doing is swaying side to side with the occasional swing of her arm. “What?”

“I said, maybe I should take the knife.”

“Why?”

“Well... you don’t need it.”

She considers my words. It takes her the time it takes paper to burn.

“No thanks. I think I’ll hold on to it.” She increases the tempo of her dance, whirling away from me. I decide to try a different approach. I pick up her iPod and turn the volume down. She faces me again and frowns. “What is it now?”

“It’s not a good idea to have it, you know, in case the authorities ever come to the house to search. You could just toss it in the lagoon and reduce the risk of getting caught.”

She crosses her arms and narrows her eyes. We stare at each other for a moment, then she sighs and drops her arms.

“The knife is important to me, Korede. It is all I have left of him.”

Perhaps if it were someone else at the receiving end of this show of sentimentality, her words would hold some weight. But she cannot fool me. It is a mystery how much feeling Ayoola is even capable of. I wonder where she keeps the knife. I never come across it, except in those moments when I am looking down at the bleeding body before me, and sometimes I don’t even see it then. For some reason, I cannot imagine her resorting to stabbing if that particular knife were not in her hand; almost as if it were the knife and not her that was doing the killing. But then, is that so hard to believe? Who is to say that an object does not come with its own agenda? Or that the collective agenda of its previous owners does not direct its purpose still?

Ayoola inherited the knife from our father (and by “inherited” I mean she took it from his possessions before his body was cold in the ground). It made sense that she would take it — it was the thing he was most proud of.

He kept it sheathed and locked in a drawer, but he would bring it out whenever we had guests to show it off to. He would hold the nine-inch curved blade between his fingers, drawing the viewer’s attention to the black comma-like markings carved and printed in the pale bone hilt. The presentation usually came with a story.

Sometimes, the knife was a gift from a university colleague — Tom, given to him for saving Tom’s life during a boating accident. At other times, he had wrenched the knife from the hand of a soldier who had tried to kill him with it. Finally — and his personal favorite — the knife was in recognition of a deal he had made with a sheik. The deal was so successful that he was given the choice between the sheik’s daughter and the last knife made by a long-dead craftsman. The daughter had a lazy eye, so he took the knife.

These stories were the closest things to bedtime tales we had. And we enjoyed the moment when he would bring out the knife with a flourish, his guests instinctively shrinking back. He always laughed, encouraging them to examine the weapon. As they oohed and aahed, he nodded, reveling in their admiration. Inevitably, someone would ask the question he was waiting for — “Where did you get it?” — and he would look at the knife as though seeing it for the first time, rotating it until it caught the light, before he launched into whichever tale he thought best for his audience.

When the guests were gone he would polish the knife meticulously with a rag and a small bottle of rotor oil, cleaning away the memory of the hands that had touched it. I used to watch as he squeezed a few drops of oil out, gently rubbing it along the blade with his finger in soft circular motions. This was the only time I ever witnessed tenderness from him. He took his time, rarely taking note of my presence. When he got up to rinse the oil from the blade, I would take my leave. It was by no means the end of the cleaning regimen, but it seemed best to be gone before it was over, in case his mood shifted during the process.

Once, when she thought he had gone out for the day, Ayoola entered his study and found his desk drawer unlocked. She took the knife out to look, smearing it with the chocolate she had just been eating. She was still in the room when he returned. He dragged her out by her hair, screaming. I turned up just in time to witness him fling her across the hallway.

I am not surprised she took the knife. If I had thought of it first, I would have taken a hammer to it. ●

Illustrations by Zakiya Noel for BuzzFeed News.

Text from the book My Sister, the Serial Killer © 2017, 2018 by Oyinkan Braithwaite. Published by arrangement with Doubleday, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Oyinkan Braithwaite is a graduate of creative writing and law from Kingston University. In 2014, she was shortlisted as a top-10 spoken-word artist in the Eko Poetry Slam, and in 2016 she was a finalist for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize. She lives in Lagos, Nigeria.

Her debut novel My Sister, the Serial Killer is available now (UK edition here).