The journalists at BuzzFeed News are proud to bring you trustworthy and relevant reporting about the coronavirus. To help keep this news free, become a member and sign up for our newsletter, Outbreak Today.

NEW DELHI — An app used by hundreds of thousands of immigrants to find friends, lawyers, therapists, and even dates has been transformed into a space for people to express their deepest fears about the coronavirus, health care, ICE, and the Trump administration.

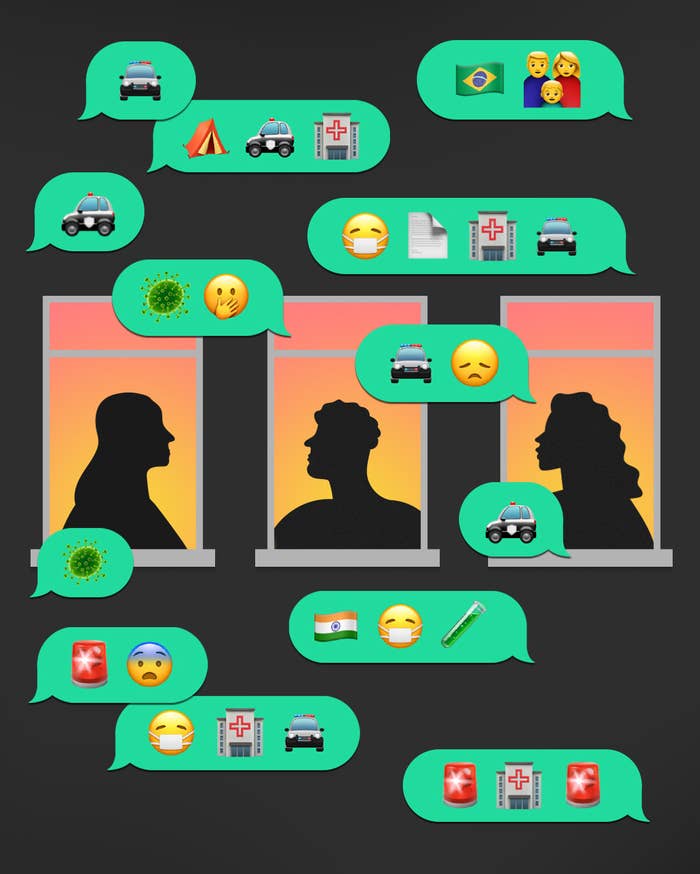

Messages sent by Homeis users to community managers on the app about IRL meetups, social events, and cultural programs have been replaced with thousands of panicked DMs about COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus.

The DMs, screenshots of which were reviewed by BuzzFeed News, are a window into the world of anxiety and uncertainty experienced by immigrants in the US during the coronavirus pandemic.

The relentless questions are from people afraid of losing their jobs and their visa status, and those who are displaying symptoms of COVID-19 but are afraid of getting tested because of the bewildering and expensive US health care system. Others are worried about being picked up by ICE while at a hospital, contracting the virus in detention, or being deported.

“Dry cough, painful throat, fatigue...no fever, but can’t ignore it in the present situation. Need your advice. No medical healthcare.”

“My husband has contracted the dreaded COVID 19. I desperately want him to come home to me and our three children. We are looking for a plasma donor…”

“An employee at the company I work in died of coronavirus. None of us were tested…”

“I am undocumented and I have all the symptoms...how can I do a check up on myself?”

Ran Harnevo, the CEO of Homeis, said the app’s users have tripled since the pandemic began. “We’re basically a COVID-19 helpline now,” he said.

Homeis is a kind of social networking app for immigrants, on which users can sign up to one of the different “communities” available: South Asian, French-speaking African, Hispanic and Latin American. Once they do, they can exchange messages with people who volunteer their time to help new app users find services, classes or jobs that they might be looking for, and thousands of other members on the app from that same community, meet members at Homeis hosted events in their cities or organize meetings of their own, find services and even advertise small businesses. Additionally, the Homeis front page also has a constantly updated series of news posts related to the concerns of that particular community, as well as links for chats with immigration lawyers, therapists and now, doctors.

Many Homeis app users had problems that preexist the coronavirus crisis and have struggled to navigate the US health care system. They are often wrongly diagnosed, sometimes to prevent them from entering the country — a judge recently blocked the Trump administration’s efforts to stop immigrants who cannot afford health care at the border. Often, they are simply unable to find a doctor they can trust.

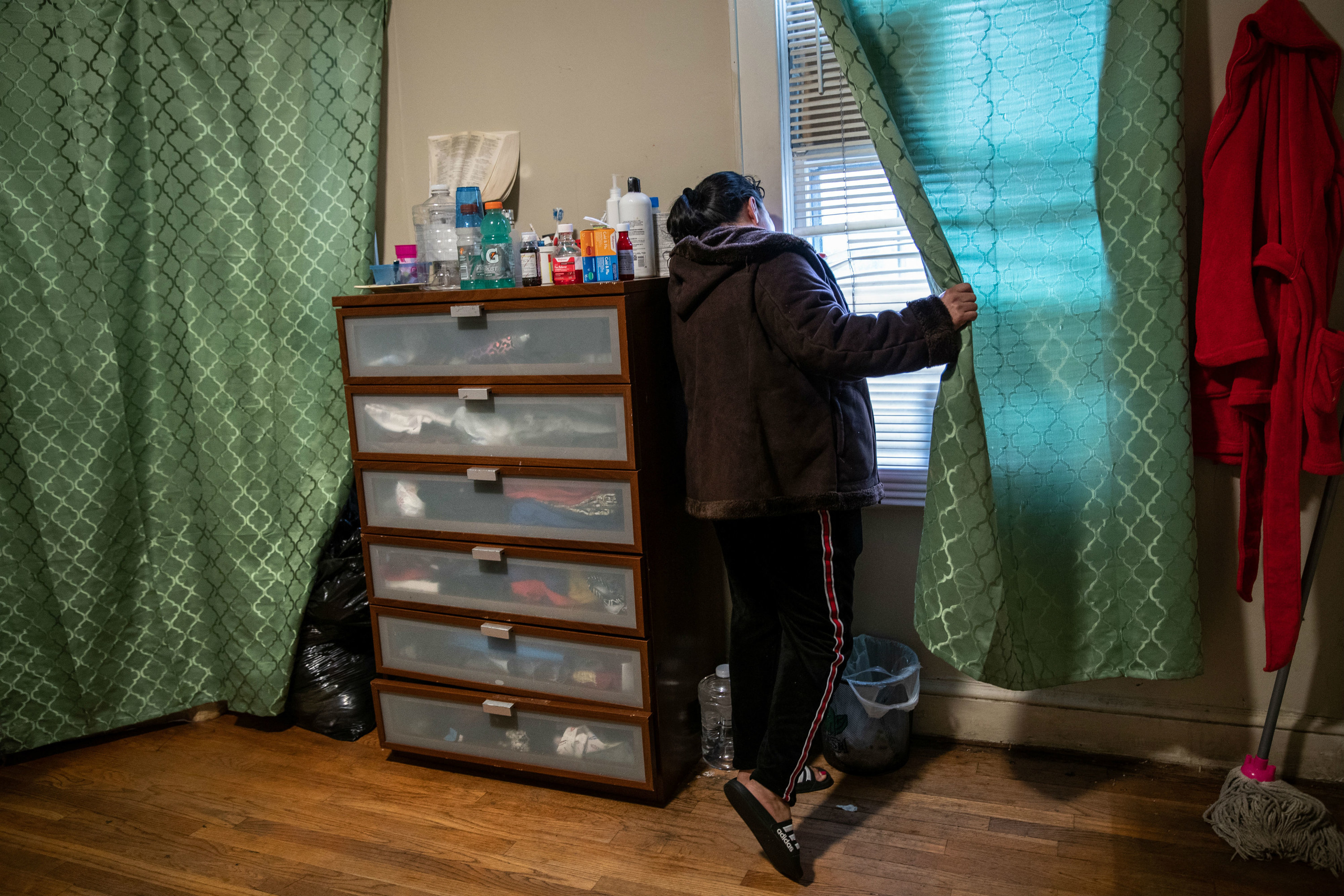

M. moved to the US from Mexico in the ‘90s. The loneliness of self-isolation is nothing new for the 40-year-old, who learned in 2017 that she could no longer hug her children for fear of passing on a highly infectious skin condition. Over the phone from Las Vegas, she described her condition on the condition of anonymity. On most days, she said, she felt as though “1 million invisible ants” were moving around under her skin, biting her from the inside. For three years, M. has slept on a towel on the floor of her bathroom to keep her children safe.

“I spent a lot of money on medicines, fought with doctors who misdiagnosed me, tried natural remedies...nothing worked.”

When she joined Homeis last year, M. found two Mexican doctors in the US who were finally able to diagnose her condition. “The biggest difference was that these doctors took me seriously.”

As the coronavirus spreads across the world, infecting and killing medical professionals, the Trump administration has continued to bar entry for foreign health care workers who could make up for the shortage of doctors and nurses. For immigrants who are already in the US, the fear of falling sick is amplified by financial insecurity and the paranoia of being deported at any moment. Now several thousands are turning to their communities on Homeis for advice and support.

If you're someone who is seeing the impact of the coronavirus firsthand, we’d like to hear from you. Reach out to us via one of our tip line channels.

Harnevo had meant for Homeis to be a social network among immigrant groups in the US to remain connected with their culture. Harnevo, who grew up in Tel Aviv, sold his first US company, a video syndication platform called 5Minute Media, to AOL for $65 million in 2010. He then began working on Homeis, a name that sounds like “home is” or “homies,” depending on the accent of the user. Harnevo was convinced that immigrants like him were seeking both — their home and their people. (Homeis is free to download and currently doesn’t feature any advertisements.)

“The internet has always been broken for immigrants,” Harnevo told BuzzFeed News over the phone from New York. “There is no safe space for us online.”

When you register on Homeis, the app asks you to select the country of your origin, the US state where you now live, and how long you’ve been in the country. Each member receives a message from one of the community managers, who are a mix or volunteers — for small communities — and paid employees. Like every app, being a woman on Homeis means being instantly and constantly bombarded with unsolicited greetings and requests from men, something that Harnevo said he is aware of and working to change. It’s also the reason the app has occasionally received poor reviews on the app store.

Anything else users might want to add about themselves is up to them. Several South Asian profiles reviewed by BuzzFeed News had added the names of small businesses, or offered services that they could provide to other South Asians like cooking or dance classes, career counseling, mental health support groups, and now, a COVID-19 response group.

Homeis users are mainly Indian, Pakistani, Israeli, and French-speaking immigrants from Senegal, DR Congo, and Cameroon. As growing evidence indicates that the coronavirus is disproportionately killing people of color the DMs that community managers have been receiving in the past weeks indicate why black and brown bodies in the US are the most susceptible to the coronavirus.

The first lesson L., a 27-year old from Burkina Faso, said she learned when she came to the US eight years ago was to look everyone in the eye. “Where I come from, you never look an elder or an authority figure in the eyes, it’s considered a sign of disrespect. But here, if you don’t do it, they’re gonna assume you’re guilty of something.”

L., who lives in New Jersey, volunteers as a community manager on Homeis for French-speaking Africans. She spoke to BuzzFeed News anonymously because she did not want to upset her employer.

“Many of the people I speak to on Homeis just got here two or three months ago in the middle of this crisis, and came to the US from primarily black communities. They don’t know what to expect, and they certainly don’t expect racism. When they encounter it they don’t know how to react,” she said. The evening we spoke on the phone, L. had been on a five-hour overnight call with a grieving man whose wife had just died and who did not know how to file the paperwork for her hospital bills.

Many app users who L. counsels must contend with a cascade of disadvantages — race, the fact that they don’t speak fluent English, that their education degrees are not recognized in the US. Many do not have the right paperwork to enable them to earn a dignified living.

“If you have a name that doesn’t sound ‘standard’ and seems too African, well, I tell them to expect racism,” she said. “Most people thank me for my honesty.”

Laura Arrazola, 31, a Yale graduate from Colombia can’t remember the last time she had a full night’s sleep.

“I’m incredibly thankful. I have a job. I am healthy. I am safe,” said Arrazola, who works for Homeis as a manager for a Hispanic and Latin American community. “At a time like this, you can really see what an ever-present fear the ICE is for our community in particular.”

Arrazola routinely receives questions about the extent of ICE’s powers, and what undocumented immigrants who are showing signs of COVID-19 should do. “Can ICE show up at the hospital and take me to a detention camp? Or the fear of contracting the virus in the camp...there is so much anxiety about how immigration authorities will deal with us if we fall sick at this present moment.”

Arrazola’s most recent call, she said, was with a construction worker in Phoenix, Arizona, who was exposed to a person who had tested positive for COVID-19 at a building site. “I told him to self-quarantine and take time off — it seems obvious that this is what he should do to keep everyone safe, but if he doesn’t go to work, he doesn’t know how to feed himself or his family.”

For weeks, Homeis has been organizing Zoom conference sessions with doctors, lawyers, and therapists for immigrants who want to talk only about the coronavirus. Behind the scenes, the app is still struggling to keep up with the flood of new users. “We have over 150,000 Mexican users on the app right now, and in the next three weeks we’re hoping to add even more Spanish-speakers from different countries,” Arrazola said. “The biggest challenge is that there is so much misinformation in these communities.”

A major concern on the app is also keeping up with rapidly evolving information. Indians in the US, many of whom are in the country on H1B visas, are particularly susceptible. If an H1B visa-holder is laid off, they have 60 days to find a job to maintain their visa status — something that is next to impossible in the present situation.

Many among the Indian community on Homeis have also rarely paid attention to mental health concerns, preferring to describe their crises as “domestic issues.” Neha Pundeer, a psychotherapist who volunteers on the app often counsels the spouses of H1B holders.

“Domestic violence is on the rise during the pandemic everywhere in the world, and the US is no different,” said Pundeer. “The women I speak with have classic signs of depression — irritability, mood swings, fatigue, sudden outbursts — but we don’t know how to recognize our own symptoms.” In the last three months, Pundeer often finds herself repeating the same tips for mental wellness to a community that was raised to be suspicious of too much self-care.

“It helps to have a routine, but that routine has to include actual breaks, time that you spend doing something nice for yourself,” Pundeer said. “Stop saying ‘I’m fine’ when you don’t feel fine.”

What makes these stories particularly heartbreaking is that all of the immigrants BuzzFeed News spoke with said they had come to the US in hope of a better life — an American dream that included better jobs, education, and doctors for themselves and their children. M. survived gun violence as a teenager in Mexico, and when she moved to the US she gave up a white-collar job as a company executive in Mexico to restart life in Chicago as a cleaner, then working as a waitress, soon working five jobs a week with no time off. When she fell in love, she said she waited until she was financially stable to have children. Soon after that, she lost her husband to a horrific workplace accident. “I’ll do whatever it takes you know,” she said. “I’m not a bad person just because I’m an immigrant.” ●