About 7,000 Americans every year receive a liver transplant — and with it, a new lease on life. But another 1,500 on the waitlist die before they are matched with a donor.

Now the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), the agency that decides which patients receive donor organs, is planning to change the way livers are distributed across the country.

The current rule, which says that livers go to patients relatively close to where the donor died, has come under fire because it means that the chances of getting an organ can depend more on where you live than how sick you are.

The new rule, if approved, would instead allow regions with a high proportion of organ donors, relative to their local waiting list, to send livers to regions with a lower proportion of donors — even if that means a cross-country plane ride.

The architects of the new model estimate that transportation costs could grow from $269 million per year to $345 million, and that an average transplant would cost $4,700 more, but argue that the overall spending on transplant care would fall as more people became healthy faster. UNOS declined to comment on the cost, but said the method could save 52 additional lives every year. It would be the biggest revision to liver allocation rules since 2002.

But transplant surgeons are in uproar over the proposal, which was released for public comment earlier this month. Critics say the new scheme will be expensive to implement and the logistics of long-distance transport will nullify any small benefits for patients. Some question the very principle of redistributing available organs, and say it would be better to focus on recruiting more donors.

“There’s a relatively wide split in the liver community,” James Trotter, medical director of liver transplants at Baylor Scott & White Health, who opposes UNOS’s proposal, told BuzzFeed News. “My personal belief is that it won’t have a substantive impact on improving overall outcomes in liver transplant candidates.”

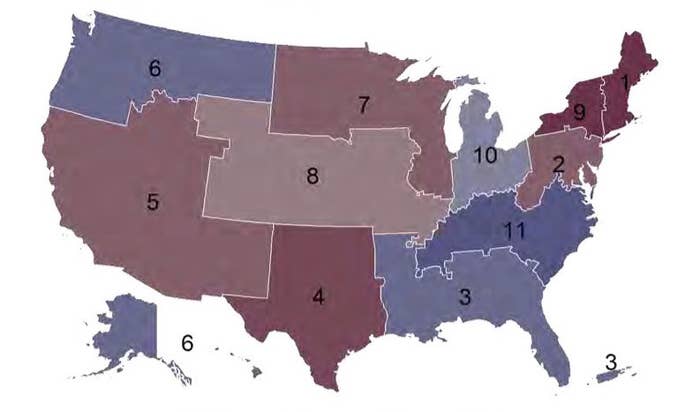

Organs are costly to transport over long distances and livers are only viable for up to 12 hours. So UNOS’s allocation policy so far has favored local transfers within 11 designated “districts” in the continental US.

Once a liver becomes available in a given district, a transplant recipient is chosen based on their “MELD” score — an aggregation of factors that indicates how likely they are to die in the next three months. The higher the score, the closer the patient is to death — or to the next liver that becomes available in their district.

But this system creates a problem. “You do have to get much sicker in one part of the country than another to get a liver,” Ryutaro Hirose, professor in clinical surgery at the University of California, San Francisco, who chairs the UNOS Liver and Intestine Committee, told BuzzFeed News.

Take Louisiana, for example, which has a relatively large pool of available organs compared with other states. Half the transplants performed there are on people with scores under 30 — patients who are sick, but may be able to work from home, for example. But in southern California, most transplant recipients are in the ICU.

“If we could instantaneously transport a liver from one area of the country to the other with a magical transporter, that would be the most fair system — but we don’t have that and that’s not practical,” Hirose said.

The committee’s new proposal, he said, sought to create something that would most closely resemble a single national list.

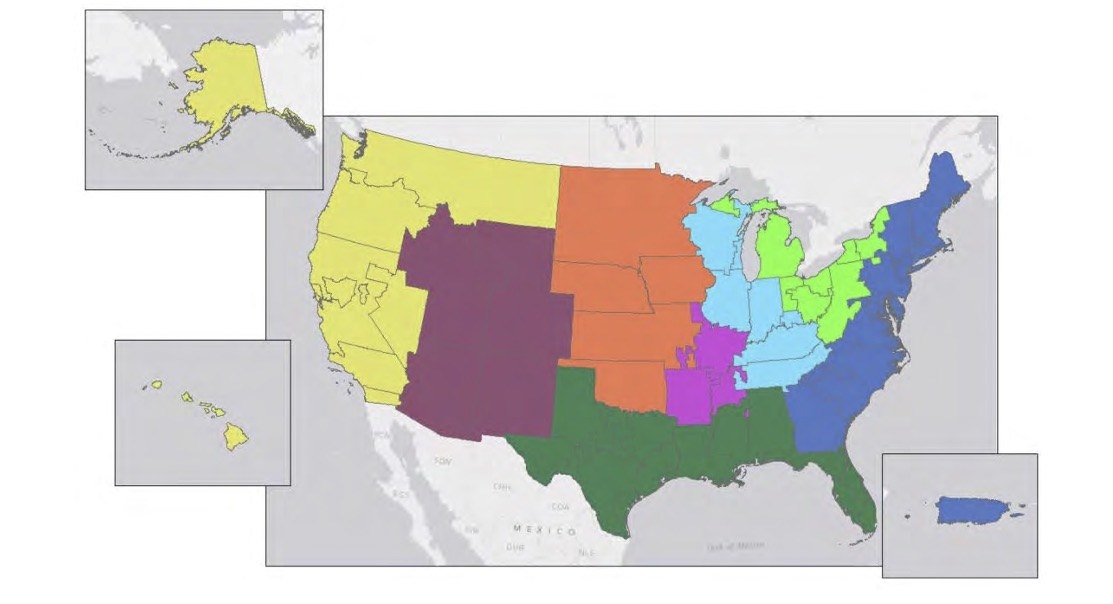

UNOS’s new system would erase some district borders, to create eight regions instead of 11. As a result, areas with more donors would supply zones in which there are more patients with higher MELD scores. (A similar geographic disparity happens with other types of organ donations. This spring, UNOS’s Thoracic Committee suggested allowing sicker heart patients to qualify for donor hearts from farther away. That proposal also incited fierce debate.)

Hirose said that depending on the public response to the new plan, the committee could consider another revision, and another session of public comment, before the proposal is put into effect.

But critics like Trotter expect that the proposal will pass despite the laundry list of objections, among them the contention that the mathematics underlying the re-districting relied on limited data.

“My biggest worry is that this is not really going to change the problem — it’s a little bit of a BandAid,” Daniela Ladner, associate professor of surgery at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, told BuzzFeed News.

Ladner and her colleague Sanjay Mehrotra, a professor of engineering at Northwestern, have built an alternative distribution plan, one that they argue will save 85 lives every year — 33 more than the UNOS’s proposal promises. Also, the proposal that UNOS backs will not adapt easily to changing factors — such as more donors one year and fewer the next. They say UNOS is rushing to implement a suboptimal system while ignoring a potentially more effective solution.

The Northwestern model, which is currently under review at a peer-reviewed journal, favors hyper-local distribution of organs that would allow transplant center and offices that already have relationships with their neighbors to draw on those ties. Instead of drawing hard borders, the Northwestern model would optimize matches across the entire country based on severity of illness and the distance to the donor liver.

The UNOS proposal, for example, divides Tennessee in half, forcing offices in each side of the state to work with partners who are farther away. Mehrotra and Trotter point to this example as proof that the benefits of the model will not be worth the ensuing chaos.

“What if you went to Federal Express and said, 'How would you solve this problem?'"

Another criticism is that the UNOS Committee did not invite the academic community or industry experts to propose alternative distribution models. Rather, the group settled on a new scheme first, then asked the transplant community for comment.

Private shipping companies, for example, may have had good solutions, Trotter said. “What if you went to Federal Express and said, ‘How would you solve this problem? You’re a multi-billion-dollar company whose entire business is focused on moving products around in the most rapid and efficient manner possible — what do you think?’”

Richard Gilroy, medical director of liver transplantation at Intermountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, Utah, is among those who oppose the idea of moving organs cross-country. Gilroy has studied donor trends in the US and was part of the UNOS Liver Committee until earlier this year, but does not support the new proposal.

A more effective, less chaotic, and potentially less costly solution, he said, could be to just recruit more donors in regions that are struggling with waiting lists.

For example, Philadelphia has among the highest rates of organ donation in the country, whereas New York has nearly the lowest. “That difference shouldn’t exist over 94 miles,” he said, and is likely due to differences in the way the two cities handle donor recruitment.

This is not the first time transplant surgeons have spoken up. At a meeting last year, where UNOS presented the current proposal, a majority of the audience — surgeons and transplant professionals — opposed it in an informal vote.

“After that it was like, why don’t you burn it and start from scratch?” Timothy Schmitt, director of transplants at the University of Kansas Hospital, who opposed the motion then, told BuzzFeed News.

If the new rule goes into effect, he expects the University of Kansas Hospital will perform fewer transplants over the next five years. In response, doctors are likely to simply inflate their patients’ MELD scores to compensate. With the new proposal, he said, “we’d have more complexity, more costs, and more death.”

CORRECTION

James Trotter is the medical director of liver transplants at Baylor Scott & White Health, not Baylor Health Care System.