The Food and Drug Administration detected chemicals linked to cancer in in supermarket staples such as cooked meats and pineapple, the agency acknowledged Tuesday, and found the highest levels in chocolate cake with chocolate frosting.

The agency tested for these “fluorinated” chemicals, also called “per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances,” or “PFAS” chemicals, because they are widely found in water-resistant packaging and consumer products, and used to manufacture them.

“Overall, our findings did not detect PFAS in the vast majority of the foods tested,” the agency said in a statement. While the agency did not see “a food safety risk” in its sampling, it added, “current evidence suggests that the bioaccumulation of certain PFAS may cause serious health conditions.”

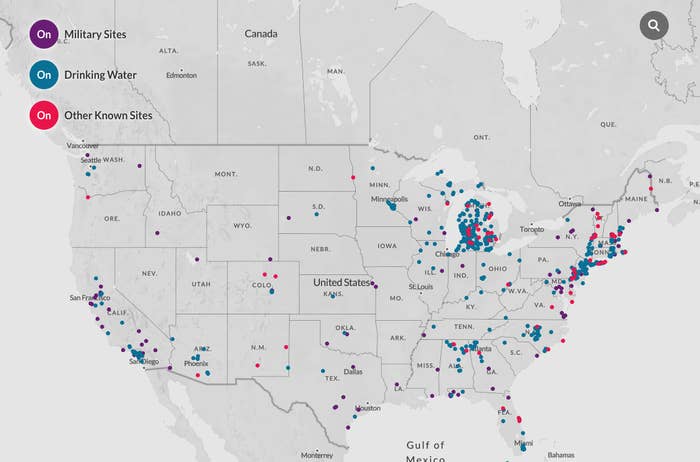

About 610 locations in 43 states, serving an estimated 19 million people, have PFAS in the drinking water, according to the Environmental Working Group and the Social Science Environmental Health Research Institute at Northeastern University.

These are often near chemical plants or near airports or military sites where fire-fighting foams containing the compounds are used in training exercises. For example, the agency also detected the chemicals in cows’ milk at a dairy in New Mexico and produce grown in North Carolina — both at sites where the chemicals have contaminated the drinking water.

PFAS chemicals are currently largely unregulated, but the ubiquity of these “forever chemicals” in water systems has spurred a raft of legislation to monitor and restrict their use and release, and some states are taking steps to limit them in the water supply. The Environmental Protection Agency last year said it would consider monitoring and limiting some compounds in the water, and announced in February a road map to take steps toward that end.

The FDA’s results mark the agency’s first foray into testing food products systematically for these chemicals, as well as from contaminated sites. Previously, the FDA has tested food packaging for traces of some kinds of PFAS chemicals and done some food tests in milk, cranberries, and some seafood. The new results were first presented last month at the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC) conference in Helsinki, Finland.

Researchers said it’s the federal government’s acknowledgement that the PFAS contamination problem stretches beyond drinking water systems.

“The newsworthy point from my perspective is the fact that this reveals the FDA is interested in these questions and is taking actions,” Christopher Higgins, a civil engineering professor at the Colorado School of Mines told BuzzFeed News.

The FDA tested 91 foods, including fresh produce, baked goods, and meat and fish. PFAS chemicals were found in 14 samples, including in raw pineapple, ground turkey, oven-roasted chicken, and boiled shrimp.

“This is the first time the FDA has tested for PFAS in such a highly diverse sample of foods,” acting Commissioner Norman Sharpless and Deputy Commissioner Frank Yiannas said in the statement.

“Overall, the FDA’s testing to date has shown that very few foods contain detectable levels of PFAS,” added the statement. “However, we know that levels may not be uniform and there is more work to be done.”

Higgins said he considered these results preliminary, and while the chocolate cake levels were surprising, he would take them with “a grain of salt.”

The Environmental Working Group, which advocates for awareness of the chemicals, said in a statement that the agency had “dismissed” the gravity of its findings.

“FDA routinely underestimates the risks chemicals pose, especially the risks posed by food chemicals that migrate from food packaging into food, including PFAS chemicals,” EWG senior scientist David Andrews said.

East Carolina University toxicology professor Jamie DeWitt told BuzzFeed News that she was concerned about the results, because they “demonstrate that industrial contaminants that are released into the environment can get into our food supply.”

The risk would vary, she said, based on how much contaminated food or water a person consumed, and how frequently. “I would be concerned if this was a consistent part of my diet every day, or my child’s diet every day.”

“The issue isn’t one slice of cheese or cake, it’s a lifetime of exposure to multiple PFAS from multiple sources.”